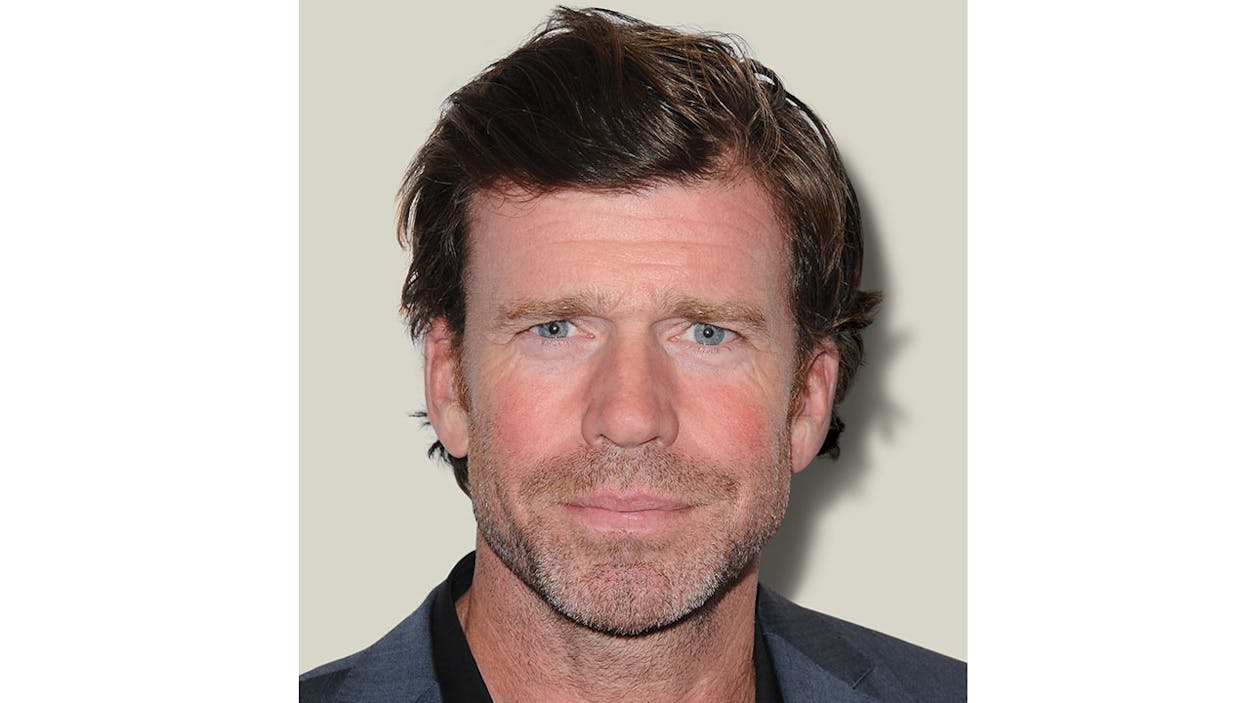

As a kid, Taylor Sheridan figured he’d be a lawman. His family was full of them, the most famous being former deputy U.S. marshal Parnell McNamara, who graced the cover of this magazine eighteen years ago. McNamara worked out of Waco, not far from the Sheridan family’s Bosque County property, and young Taylor saw him as a role model. “I thought I’d do something like that: go out during the day hunting bad guys and come home at night to the ranch.”

Instead, he wound up playing a cop on TV. Sheridan’s childhood plans took a tumble when his parents divorced in 1991 and had to sell the ranch. He went off to college in San Marcos, where he admits he was a “miserable student,” majoring in theater “because it sounded like fun and the girls were pretty.” He was looking for a job in an Austin mall one day when a talent scout approached to ask if the rock-jawed youth was interested in modeling. “I said, ‘No, but do you guys handle actors?’ ” Sheridan recalls.

The scout bought him a plane ticket to Chicago for an audition. “I’d never been on a plane before. I cashed the ticket in, which you could still do at the time, and drove on up.” After some commercials, he started getting one-off TV gigs and, eventually, a recurring part in Sons of Anarchy, as deputy chief of police David Hale. He had the role for two seasons before being killed off in the third season’s debut. By then, he was ready to get on the other side of the camera.

Most actors who write a screenplay do it because they’re unhappy with the roles they’ve been getting. But Sheridan had no desire to star in the movies he was writing. “I just lost interest in performing,” he explains. He wrote three scripts in quick succession. One of them, Sicario, an ambitious drug-trade thriller, was made into a movie last year, with Emily Blunt, Benicio Del Toro, and Josh Brolin in the lead roles. Another, Hell or High Water, comes out August 12 and features Ben Foster and Chris Pine as a pair of West Texas brothers who turn to robbing banks and Jeff Bridges as the Texas Ranger who wants to bring them down. (The film had to shoot in New Mexico for budget reasons, but Sheridan says, “We shot as close to Texas as they’d let us.”)

Bridges, captivating as an aging Ranger on his final mission, spent some time with the character’s model, Parnell McNamara, who, like all U.S. marshals, had to retire at 57. “I wrote the movie thinking about my uncle, who got forced into early retirement when he should’ve still been working,” Sheridan says. “I wanted to capture the sadness of not doing the thing you’re used to doing.” (McNamara is now the sheriff of McLennan County.)

This being a cops-and-robbers movie, there are plenty of guns, and Sheridan’s script deals with them in ways that might unsettle viewers opposed to Texas’s loose gun laws. Multiple robberies are nearly foiled by regular citizens packing heat; the end of a well-staged highway chase can be seen to suggest that, if only folks had AR-15s in their trunks, tragedy could be averted.

The ambiguities aren’t accidental, says the 46-year-old Sheridan, who grew up with guns and remembers hunting seasons when his fellow high school students brought rifles to campus in their trucks. “I believe in the Constitution—and I believe in common sense,” Sheridan says. “If you can tell my political viewpoint from the film, then I’m doing a disservice to the viewer. I don’t want to make it obvious what the movie is saying.”

- More About:

- Film & TV