Featured in the San Antonio City Guide

Discover the best things to eat, drink, and do in San Antonio with our expertly curated city guides. Explore the San Antonio City Guide

Growing up in San Antonio in the seventies and eighties, I was always delighted to spot the Olmos Dam whenever I headed south toward downtown on U.S. 281. Its appearance on my left, just before the highway’s graceful curve north of Hildebrand Avenue, meant that I was closing in on some of my favorite attractions: Kiddie Park and the San Antonio Zoo, which enthralled me when I was young, or the Japanese Tea Garden and the San Antonio Museum of Art, which appealed to my older self. In any event, I remember thinking that the hulking concrete structure seemed excessively grandiose, perhaps because of the scenic road running along the top that once linked a pair of well-heeled neighborhoods. Since I rarely saw much water impounded behind it, sometimes I wondered if the dam was even necessary, although I knew that the basin occasionally filled up after heavy rains.

In West Side Rising: How San Antonio’s 1921 Flood Devastated a City and Sparked a Latino Environmental Justice Movement (Maverick Books/Trinity University Press, September 7), Char Miller, a professor of environmental history and analysis at Pomona College, explains that city leaders constructed the dam in response to a cataclysmic flood that occurred one hundred years ago this month. But even as the new barrier helped keep downtown dry, it did nothing to alleviate the regular flooding that continued to ravage the city’s poor and predominantly Hispanic West Side. Only with the emergence of a grassroots environmental justice movement in the seventies did San Antonio officials finally turn their attention to what Miller, quoting the environmental scholar Rob Nixon, calls the “slow violence” born of municipal neglect that plagued the neighborhood.

Miller’s new book—his fourth about San Antonio, where he taught for 26 years at Trinity University before decamping for California in 2007—is an illuminating environmental history of the Alamo City with urgent lessons for the present, given the stark challenges facing all of us in the Anthropocene.

The field of environmental history—the study of the reciprocal relationship between people and the natural world—coalesced because of the environmental movement of the sixties. There was revolution in the increasingly toxic air: Rachel Carson’s 1962 best-seller Silent Spring warned of the catastrophic effects of the deployment of pesticides such as DDT; the cellular biologist Barry Commoner sounded the alarm on the dangers of nuclear fallout; and in the summer of 1969 the polluted Cuyahoga River famously caught fire, turning Cleveland into a symbol of industrial filth and decline. The first Earth Day took place in 1970, by which point many historians had already begun paying attention to these disturbing trends.

The founding generation of environmental historians, however, tended not to focus on such contemporary struggles, looking instead to more inspiring examples from a distant era. These scholars spotlighted the crusades of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that established the national park system and emphasized the conservation of resources such as timber and water. And they generally adopted the perspective of historical figures who posited a radical disjuncture between cities and nature, captured by Henry David Thoreau’s celebrated retreat to Walden Pond in the mid-1840s because he “wished to live deliberately,” away from the trappings of urban society (while still making frequent visits to the town nearby).

But as the discipline matured in the 1980s and 1990s, environmental historians—then, as now, a largely white group—started to draw connections between urban areas and the landscapes in which those areas are embedded. Their work grappled with issues of resource exploitation and public health, and in more recent years, many of them have focused on how race and class have produced environmental inequalities in our cities. For example, one scholar revealed how Manhattan’s antebellum elite “tamed” their metropolis at the expense of impoverished New Yorkers by forcing livestock operations to the margins of the island and sprinkling trees and green spaces in wealthier enclaves. A century later, in the company town of Gary, Indiana, Black and Mexican workers at U.S. Steel were typically assigned to jobs that exposed them to higher levels of noxious pollutants than white workers faced. What’s more, they lived in closer proximity to the steel mills than their white employers and managers and were therefore afflicted by airborne wastes.

West Side Rising may conjure for some readers a more contemporary example: the tragedy of Hurricane Katrina, in which Black communities in the lowest-lying parts of New Orleans suffered disproportionately from flooding generated by the 2005 storm. Miller’s book feels in many ways like a slow-motion prequel to that disaster, set 550 miles west on I-10.

In his prologue, Miller carefully considers the geography of San Antonio, explaining why the city has long been susceptible to inundation. A key factor is San Antonio’s proximity to the Balcones Escarpment, a geographical fault zone that, as Miller notes, runs “like a lopsided smile” from just east of Del Rio to just north and east of Dallas. This landform marks the boundary between the arid conditions of the Great Plains and the more humid weather of the Coastal Plain, such that “the climate can toggle between deluge and drought.” Moreover, when the Spanish arrived in 1718, they built their settlement at a narrow point between the San Antonio River to the east and a set of small streams to the west, some of which slow to a trickle in dry weather. But, Miller writes, “when rain falls, they can rise quickly, powerfully, and fatally,” often merging with the swollen San Antonio River itself and causing extraordinary damage, as happened in 1819, 1845, and 1865.

It was just such an event that struck the city on September 9 and 10, 1921, when a tropical depression dumped as much as seventeen inches of rain on parts of San Antonio. Compounding matters, as a federal forester observed at the time, was “a greed for land” among ranchers north of the city that had led to unwise management practices, especially overgrazing, which “stripped the already thin soil of vegetation so that even modest storms could generate major floods.” The deluge pummeled the whole city, but the West Side took the worst of it, as its shallow creeks soon spilled over and made quick work of the “jacal” district—named for the area’s early homes made of wattle and daub—which was occupied primarily by impoverished Mexicans.

One adolescent, Francisco Gutiérrez, managed to save himself and his five-year-old nephew by loading the boy onto his back and clinging to a tree for hours.

Miller tallies roughly eighty dead or missing after the flood, the vast majority of whom were Hispanic West Siders, including nine members of the Zepeda family who, as they fled their home on Alazán Creek, were broadsided by a waterborne house that had slipped its foundation. One adolescent, Francisco Gutiérrez, managed to save himself and his five-year-old nephew by loading the boy onto his back and clinging to a tree for hours while “battered black and blue by floating wreckage.” The San Antonio Express singled this out as “perhaps the outstanding heroism of the flood.”

Following a massive rescue and cleanup operation supported by the Red Cross, Cruz Azul Mexicana (a female-led community organization), and hundreds of U.S. soldiers, the Army Corps of Engineers prepared a report that did little but recommend halting future housing development in the West Side floodplain so as to limit risk to potential residents. Incredibly, the city also entertained a local committee’s suggestion to divert floodwaters from Olmos Creek to the West Side, which would have compounded future floods—indicating, for Miller, that members of the committee regarded the neighborhood as a “sacrifice zone.” Though the city’s Anglo power brokers recognized that this would have been a step too far, they basically allowed the West Side to languish; their focus was almost exclusively on protecting the downtown core.

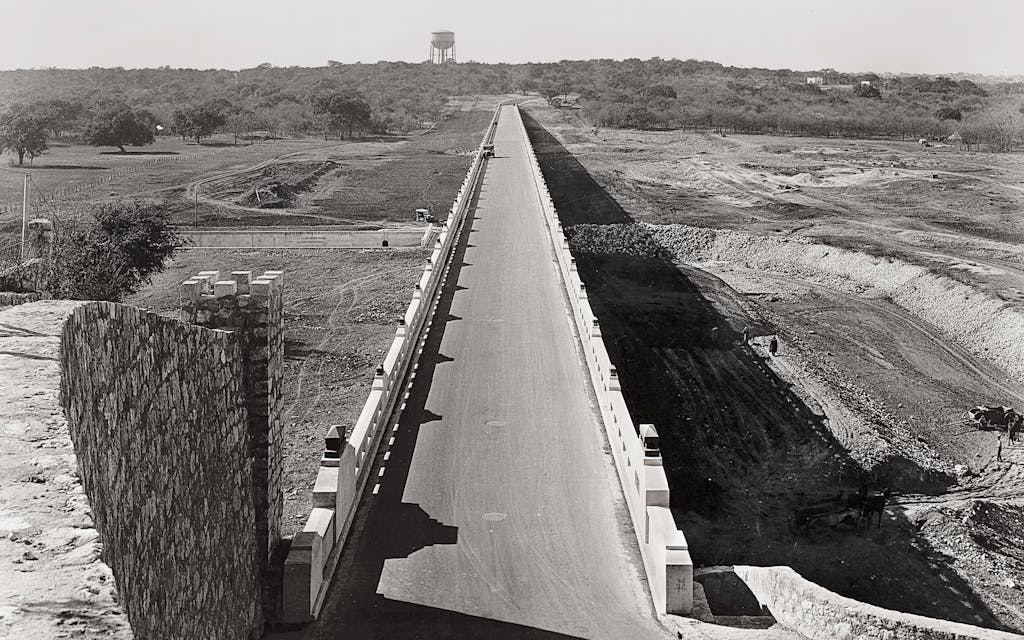

The $1.6 million Olmos Dam—sixty feet high and nearly two thousand feet long—was completed in December 1926. With the city center now secured, the dam helped spur a building boom that transformed downtown, leading to the erection of iconic structures such as the Milam Building (1928) and the Smith-Young Tower (1929), now the Tower Life Building. In Miller’s evocative phrasing, “The new skyscrapers stood like a profane gesture to Mother Nature.”

The dam encouraged suburban growth as well, including the upscale community of Olmos Park, perched on elevated land west of the barrier and further sheltered from the growing city by the new floodplain below, where—because of the potential for impounded water—no one could safely build. Reinforcing this spatial segregation was a deed restriction explicitly stating that property in Olmos Park could not be “sold, conveyed or leased to any person who is not of the Caucasian race.” West Siders, meanwhile, faced a “catch-22: properties in the district were too low in value to protect, but their value could not increase until flooding was prevented.”

Relief was minimal, and the neighborhood was thus swamped with brutal regularity, as in 1951, when the creeks overflowed after a heavy rain, killing three residents and damaging more than 150 houses. Meanwhile, gawkers flocked to the Olmos Dam to marvel at its catchment. Miller is blunt in his analysis: “That such levels of death and devastation in the face of flooding were an expected outcome reflected the longstanding disregard for those living on the West Side.”

With city officials unwilling to act, West Siders finally seized the initiative after yet another destructive flood struck their neighborhood in 1974. Communities Organized for Public Service (COPS)—a new and powerful grassroots organization with West Side origins—took up the fight, modeled in part on the earlier work of Cruz Azul Mexicana as well as more recent efforts to draw attention to the issue by congressman (and native West Sider) Henry B. González. At a dramatic meeting of the San Antonio City Council, hundreds of COPS supporters showed up, some of whom had dug into the city’s archives and unearthed a 1945 municipal master plan that, had it been implemented, would have guarded against the latest disaster. This revelation astonished the city’s new mayor, Charles Becker, who gave the city staff four hours to allocate the funds needed for the long-ignored proposal, then called the council back later that evening to hear the results. “Flood control,” Miller writes, “was suddenly and emphatically on the city’s agenda,” and within three months the city passed a $46.8 million bond initiative for fifteen West Side drainage projects.

The COPS crusade against environmental injustice soon led to an even bolder initiative: challenging the power structure that had helped to produce such inequalities in the first place. For decades the city charter had stipulated the election of city council members on an at-large basis, which had imbued a largely white North Side coalition with lopsided influence. But with help from the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund as well as the U.S. Department of Justice, COPS pressed for a revised charter that in 1977 established ten city council districts. The measure was narrowly approved, with West Siders voting nearly nine to one in favor of the change.

In short order, Latino activists trained “at the University of COPS” fanned out across the nation “with the goal of bringing Hispanic and other underrepresented communities into the political process”—making San Antonio, in Miller’s estimation, a cradle of a broader Latino justice movement, environmentally and otherwise. “Nature, the source of so much death, damage, and disarray on San Antonio’s West Side, had become the catalyst of its residents’ liberation.”

Forgoing the pessimistic tone that suffuses many environmental histories, West Side Rising ends on a decidedly upbeat note, as Miller explores twenty-first-century improvements to the city’s river system that have enhanced the quality of life on the West Side and in San Antonio more broadly. But one of his more important messages is consonant with a key theme in the environmental history literature: namely, that “natural” disasters are often the byproduct of human choices.

Such decisions shaped one of the state’s most recent calamities—the loss of power and water that killed hundreds of Texans during this past February’s brutal cold snap. A major factor was the determination in 1999 by then-governor George W. Bush to pursue greater energy independence for the state, which meant there was insufficient redundancy when the power grid faltered. (The most recent legislative session did little to solve this issue.) Likewise, the state had chosen, years earlier, to allow multiple natural gas facilities, which fuel many of our electric plants, to go without the necessary weatherization. And while Texans of many backgrounds were affected by the punishing freeze, the state’s most vulnerable residents were hit hardest.

Extreme weather, much of it exacerbated or even brought on by climate change, is the catalyst for many of the crucial issues Texas faces right now: hurricanes in Houston, drought in El Paso, the vanishing Edwards Aquifer, invasive species mucking up our waterways, and the current ERCOT advisories regarding energy curtailment. Many Texans look at these challenges and throw up their hands in despair. But Miller’s book offers an inspiring account of what can be achieved, at the local level at least, by motivated people with right on their side.

Andrew R. Graybill is a professor of history and the director of the William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies at Southern Methodist University.

This article originally appeared in the September 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “In the Wake of the Flood.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Books

- Flooding

- San Antonio