Fred Baldwin and Wendy Watriss arrived in Texas in 1971 as globe-trotting photojournalists. They had met only a year earlier, but they were inseparable. Over the next fifty years, they would become celebrities in the global art scene, familiar to thousands simply by their first names, as the visionary founders of the pioneering Houston art organization FotoFest, which hosts the FotoFest Biennial, one of the world’s premier photography festivals. Always Fred and Wendy, they were a package deal.

So when Fred died suddenly on December 15, at the age of 92, I didn’t think first about what a larger-than-life figure he was. I waited a few days and called Wendy, who is 78.

“It was a shock and a surprise, but at least it was very rapid, and not painful for him,” she said.

They were home alone when it happened, in the Houston bungalow they have rented since the early eighties, across the street from the Rothko Chapel. It was 9 p.m., and they were sitting down to eat chicken pho. Fred was on a couch when his face went ashen and he put his right hand over his heart. “Call 911,” he said. Those were his last words.

Watriss sounded like her usual self, warm and forthright. “It takes a while to come to terms with it in full,” she said. “It would have been helpful to have two or three minutes to say how important the relationship was and how we cared about each other and accomplished a lot.” She and Baldwin felt far from finished. “We had so many projects,” she said. “Some of that will happen. Some probably won’t.” I suspected their dining table was piled high with paperwork, as always. Their personal archives fill a room of their home and two outbuildings with boxes. She still hopes to deliver all that to the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin this year. Even before Fred died, they had an assistant for the project; but the scale of his extraordinary life alone has made poring through it an almost unenviable task.

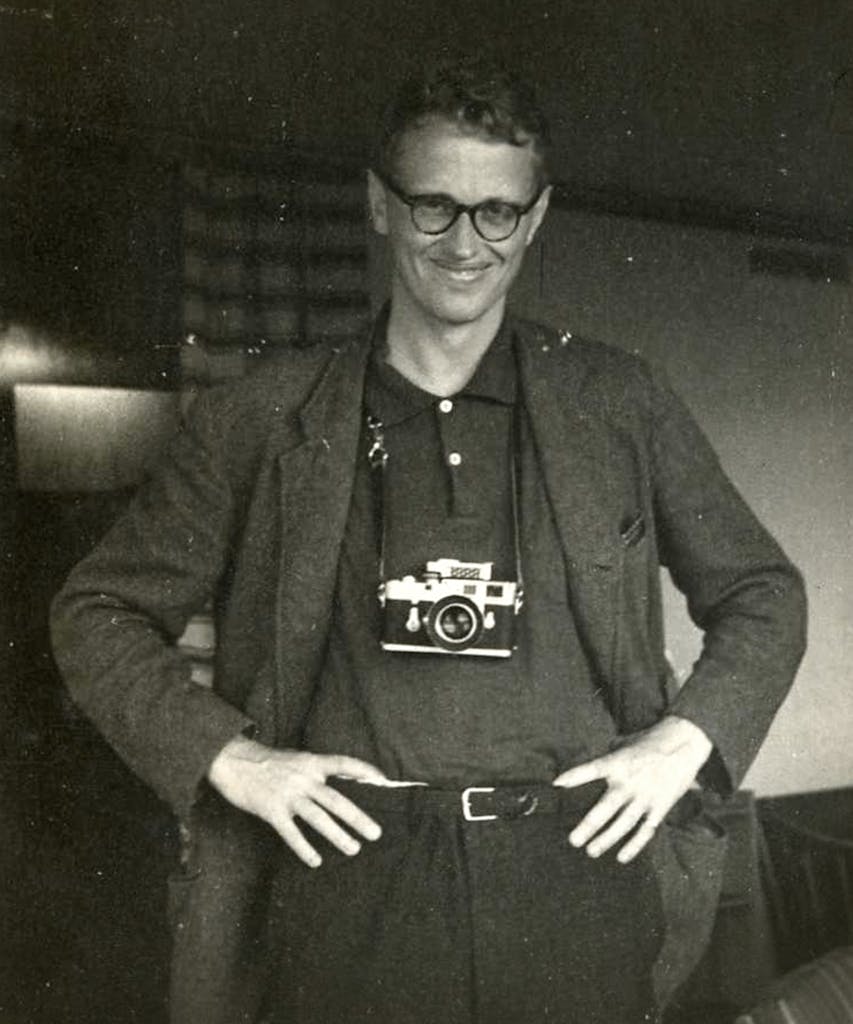

Baldwin was born in Switzerland, to a wealthy family from the American South. He experienced a peripatetic childhood. His father, a diplomat, died when he was five, but his mother kept them moving. “There’d be a summer place that would be different from the winter place, and then the schools started,” he said when I spoke to him in 2019. He was expelled more than once and escaped what he felt would be a “life sentence”—running a family factory in Savannah, Georgia—by joining the Marines and heading to the front lines of the Korean War, where he took his first photographs and was wounded. After the war, he went back to school, first in Savannah, then ultimately at Columbia University. He didn’t seriously pursue much of anything. But that would change after he met Pablo Picasso.

In 1955, the summer before his last year at Columbia, Baldwin was living in Paris and was restless about his future. He had only a superficial knowledge of Picasso’s art, but the artist was his idol—an “imaginary father” who controlled his own world, as Baldwin couldn’t seem to do. On a whim, he decided to meet his hero and drove to Picasso’s home studio, Villa La Californie, near Cannes. For three days he repeatedly knocked on the door, only to be turned away.

Baldwin was already a budding raconteur, with a lot of stories to tell, and he told them all with self-deprecating humor. Tall and lanky with wavy blond hair, heat-seeking eyes, full lips, and a sharp-angled nose, he’d charmed girls for years by writing funny letters with silly cartoons of himself. And that’s exactly how he finally sweet-talked his way into the artist’s home. Looking at a book of Picasso’s drawings as he waited in his car, Baldwin realized the artist had “a wild sense of the ridiculous” and played to it. “Dear Mr. Picasso,” he wrote, “I’m sleeping in my car on your doorstep. And each day that passes, my beard grows longer and longer. Soon I’m going to look like Moses. If you’d just let me come in and take some pictures of you, I’ll go to Florence where I have some money and shave my beard off. With hope, Fred Baldwin.” The artist’s daughter Maya let Baldwin in; Picasso wanted to see his beard. “I have an imaginary beard!” Baldwin said. Amused, Picasso let Baldwin stay a whole day and photograph him. That experience became a defining moment of Baldwin’s life and gave him a mantra he shared often: Dream. Use your imagination. Overcome your fear. And most important, take action. He finished his degree at Columbia and became a photographer.

During the next fifteen years, Baldwin would risk his life for adventurous work: He followed reindeer migrations and polar bears in the arctic. Closer to home, he photographed a Ku Klux Klan rally, traveled with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and photographed a poor white community in Savannah; the latter photos would eventually be used in testimony before Senator George McGovern’s Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs. Baldwin married and had two sons, but a messy divorce in the late sixties left him distraught. He feverishly wrote a six-hundred-page diary as “a kind of brain drain where I started with my earliest memories and worked through exactly who I was, and why I was what I was,” he said. That diary inspired much of his 2019 memoir, Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair With Freedom. Across the book’s 832 pages, the young Baldwin—spoiled, conflicted, and confused—learns to temper his ego and channel his fearless curiosity toward more humanistic goals. The narrative ends in the summer of 1970, when he meets Watriss at a New York cocktail party hosted by an Italian duchess.

Watriss was a freelance photographer and stringer based in Vienna, with assignments from Newsweek and the New York Times. “It was attraction at first sight,” she says. Very quickly, their love affair blossomed into a professional and artistic partnership that would be central to their lives for the next half century.

Baldwin and Watriss were “joined at the hip, yes; but joined at the mind, no,” says Anne Tucker, curator emerita of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s massive photography collection. “Whatever they built was a weaving of those two minds and global experiences and people they knew in the world. . . . But he could make her smile.”

Despite having recently documented the civil rights movement when they met, Baldwin had spent much of his life abroad, as had Watriss. Born in San Francisco, she grew up in Greece, Spain, and France. She and Baldwin were both “informed and at home in the world,” as she says, but they felt they didn’t understand their native country very well. Texas in particular “seemed more exotic than Bulgaria,” Watriss says. She and Baldwin conceived their first personal collaboration, the 1971 road trip they called their “Backroads of America” project, to explore the nation at their own pace and produce a documentary book.

They started out by driving across the South, living in a trailer they hauled behind Baldwin’s Mercedes Cabriolet, taking back roads that looked interesting. Finding the unexpected wasn’t hard; Watriss vividly recalls a near-mystical night of frog gigging with a family in the Mississippi Delta. They came to Texas looking for a microcosm of diverse, American frontier culture. But as they entered Texarkana, they saw an imposing courthouse typical of the Old South and about 25 Black students leaving a school. There’d been no mention of Blacks in the Texas history books Watriss had read at the New York Public Library. Evidence of a lingering plantation culture surprised them. Chasing that story, they went to Grimes County, about forty miles northwest of Houston. In the late nineteenth century, the county had glimmers of progressive politics; then, in the early 1900s, a pogrom initiated a mass exodus of Blacks. Some had remained, and Watriss says she and Baldwin saw a very clear cultural divide that they could document. “You could photograph it. And it was a perfect time, in the middle of national foment [around race relations].”

They met a Black family who invited them to park their trailer and stay for a while, photographing and interviewing Black and white residents. Watriss and Baldwin were among the first to photograph small-town Juneteenth celebrations (which predated the big urban events of today) and Black rodeos. Championing the rights of ranchers in the county, they helped scuttle the eminent domain powers of a new state agency that wanted to build lignite strip mines and power stations.

They would live in Grimes County for two years, and their project there became a template for documenting other Texas subcultures: descendants of German settlers in the Hill Country, Hispanics and migrant workers along the Mexican border, and ranchers around Alpine. “People were curious, and we had good manners,” Watriss says. “They let us stay.” She and Baldwin amassed enough documentary material to fill several books, and Dominique de Menil exhibited three hundred of their Grimes County photographs at Rice University. De Menil also invited them to live in one of the bungalows on her Montrose campus, where they settled in to write. But their bags never stayed unpacked for long. Watriss continued to produce important work of her own for a few years, including the award-winning 1982 project “The Implications of Agent Orange.” And after three trips to the Rencontres d’Arles, a major annual festival of photography in France, she and Baldwin put “Backroads of America” on the back seat.

Contemporary photography at the time was not widely appreciated as an art form. Committed to artists, ideas, and social justice, Baldwin and Watriss wanted to democratize a system they thought was too rarified. They cofounded the FotoFest organization with art dealer Petra Benteler in 1983 and launched the first FotoFest Biennial in 1986 as a month-long, citywide festival of exhibitions and lectures, with a public portfolio review component. The first international photography biennial in the U.S., it was for years one of few places where photographers could meet and present and sell their work to museums and collectors.

They started it big, purposefully, “to capture the imagination of Houston and the world,” said Steven Evans, the organization’s executive director since 2014. It worked. The biennial quickly became a phenomenon, catalyzing a global community of photographers, curators, dealers, and collectors, who continue to gather in Houston every other spring. Each biennial explores a particular region or issue of global concern. Meanwhile, the portfolio reviews enabled Baldwin and Watriss to see where photography was headed, so they also embraced new media work and installations. “It was impossible to stroll the streets of Houston in March and not feel the seismic cultural moment,” a Texas Monthly writer reported after seeing the 2002 biennial, which prominently exhibited artists experimenting with early iterations of digital technology that today is essential to the art form.

“It was a sustained vision that literally changed lives,” Tucker says. “Photographers sold work. People got tenure. . . . It gave so many photographers validation. They got books. They got shows.” It also blew open a new realm of art history. “The history of photography up to that point consisted of work from America, France, Britain and Germany, maybe Holland,” says Tucker. “FotoFest exposed every curator who came to this wealth of picture-making on other continents.” Building the collection at the MFAH, she was among the most active buyers; FotoFest enabled her to view work by thousands of photographers without the expense of global travel. “The breadth of the museum’s collection grew exponentially because of Fred and Wendy,” Tucker says. One major museum donor often sat beside her as she reviewed portfolios, elbowing her to signal that she’d pay for a print if Tucker wanted it. Tucker loved seeing photographers’ reactions when she told them to thank the lady next to her.

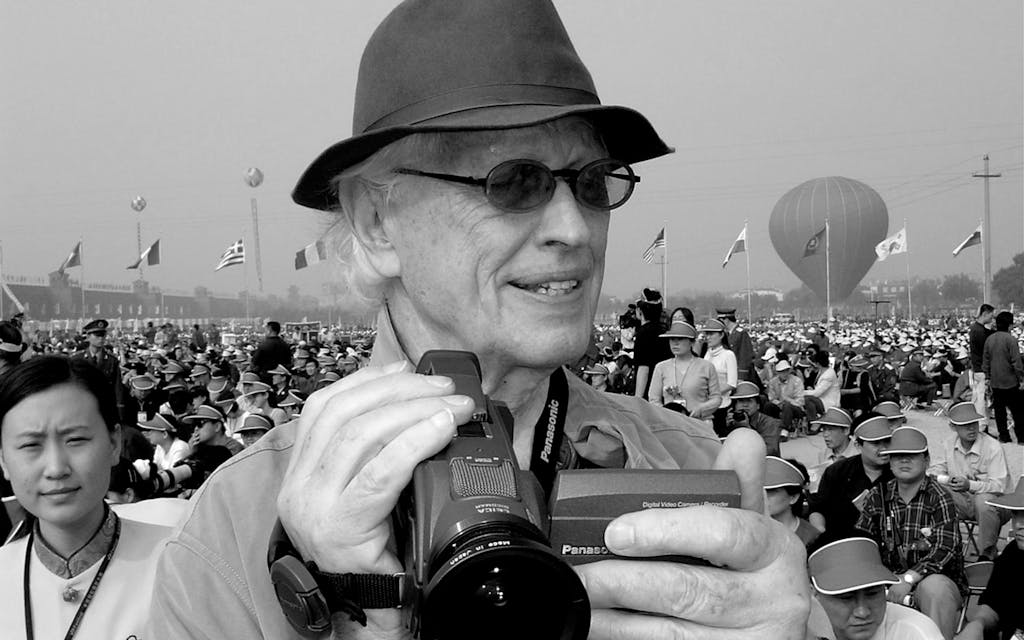

Baldwin and Watriss also established FotoFest education programs, international exchanges and traveling exhibitions. But the biennial remains its signature. (Sadly, 2020’s terrific biennial, “African Cosmologies,” opened just as the coronavirus pandemic arrived, and most of its programs were canceled. Evans has shifted 2022’s big event to the fall as insurance against a repeat.) Baldwin and Watriss remain FotoFest’s guiding lights, and Baldwin’s death won’t change that, Evans said. “Fred would want us to work harder than ever to keep everything moving.”

Watriss plans to finish a book on the history of FotoFest that she and Baldwin were writing together. “FotoFest became such an important part of our lives, it sort of took over our personal photography,” Watriss says, “but in a way [as activism] it was an extension.” She thinks the biennial succeeded because of their combined personalities, and his humor helped keep both their working and personal relationships aloft. “He had a wonderful and idiosyncratic wit. I could hear his stories over and over again, which I did, and enjoyed it,” Watriss says. “He was really engaged in living. He loved discovering things. We both did.”

Baldwin never stopped photographing. Even as age slowed him down, he kept a camera strapped around his neck during FotoFest events. “It was part of his DNA,” Evans says. “At FotoFest you never know when something’s going to happen—like, Shahidul Alam, a well-known figure from Bangladesh, might show up.” The other thing Baldwin always carried, less obviously, was his identity as a proud and loyal Marine. He kept a Purple Heart license plate on his old Mercedes, and younger veterans who saw it parked in the bungalow’s driveway often knocked on the door to thank him for his service and talk. Unlike Picasso, he didn’t hesitate to welcome them. Even the emergency medics who tried to revive Baldwin as he was dying noticed the license plate and asked Watriss about it—a moment that seemed to bring that aspect of his life full circle.

It will take her a while to unspool all that their shared work has meant, she says. Hundreds of condolence letters and emails poured in after Baldwin’s death, literally from around the world. “He would have enjoyed the attention,” Watriss says. “But the effect FotoFest has had is quite mind-blowing, and it’s nice to see that acknowledged by so many people.”

- More About:

- Art

- Obituaries

- Houston

- East Texas