Georgia O’Keeffe may have found her heaven in New Mexico, but she discovered her religion in Texas.

I’m speaking figuratively, of course, since O’Keeffe was not a churchgoer. From the fall of 1916 to early 1918, as a young professor at West Texas State Normal College (now West Texas A&M University) in the Panhandle town of Canyon, the painter reveled in being progressive and different. She danced, went to movies, rode with men in fast cars—well, as fast as cars could be, bouncing on dirt roads or no roads across the plains—and kissed a lot of guys. She was not shy about standing on a porch in the rain, wearing nothing but a loose kimono; or dressing in front of an open window when she knew she was being watched; or lying on the plains at night, gazing up at the stars, with a young football player.

We know this from alluring letters O’Keeffe wrote to the most important man in her life, her future husband Alfred Stieglitz, and other loved ones back east. Much of this correspondence was published last year in Amy Von Lintel’s book Georgia O’Keeffe’s Wartime Texas Letters (Texas A&M University Press). Von Lintel presents just the outgoing mail, to keep the focus on O’Keeffe as a strong-willed, intelligent woman at a time when women couldn’t yet vote in Texas. “Why of course I feel free—it never occurred to me to feel any other way,” the artist wrote, even as she coyly played to Stieglitz as his “little girl of the Texas Plains.”

More important, the letters expose the rapture that the budding Modern abstractionist felt as she bathed her soul in the Panhandle’s desolate landscape. Texas is where O’Keeffe learned to see, in a way no one else could. “Last night I loved the starlight—the dark—the wind and the miles and miles of the thin strip of dark that is land—it was wonderfully big—and dark and starlight and night moving,” she wrote in October 1916. Her letters revisit this theme repeatedly. “The wonderful stretch of the bare line at sunset—the stars—a train that I watched like a star on the horizon—it’s great to watch it moving such a long time—it never came close enough to be anything but a little line—the wrestle of the day—the emptiness of the night—and I like it all so,” she wrote that December.

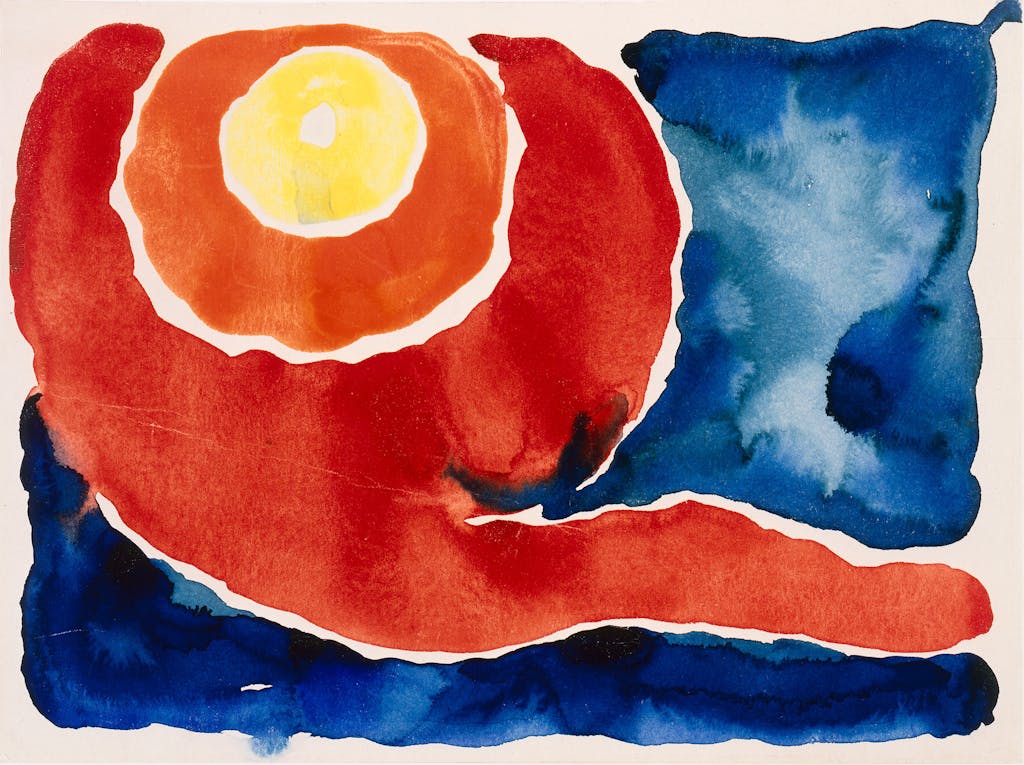

By March 1917, when she was 29, she had found her fluid, abstract visual vocabulary and produced her first important watercolor. Evening Star, with its windswept red swirl on a field of dark, pooled blue, was a breakthrough. “It’s big and it looks like Hell let loose with a fried egg in the middle of it,” she wrote. “I feel as though I’ve burst and done something I hadn’t done before.”

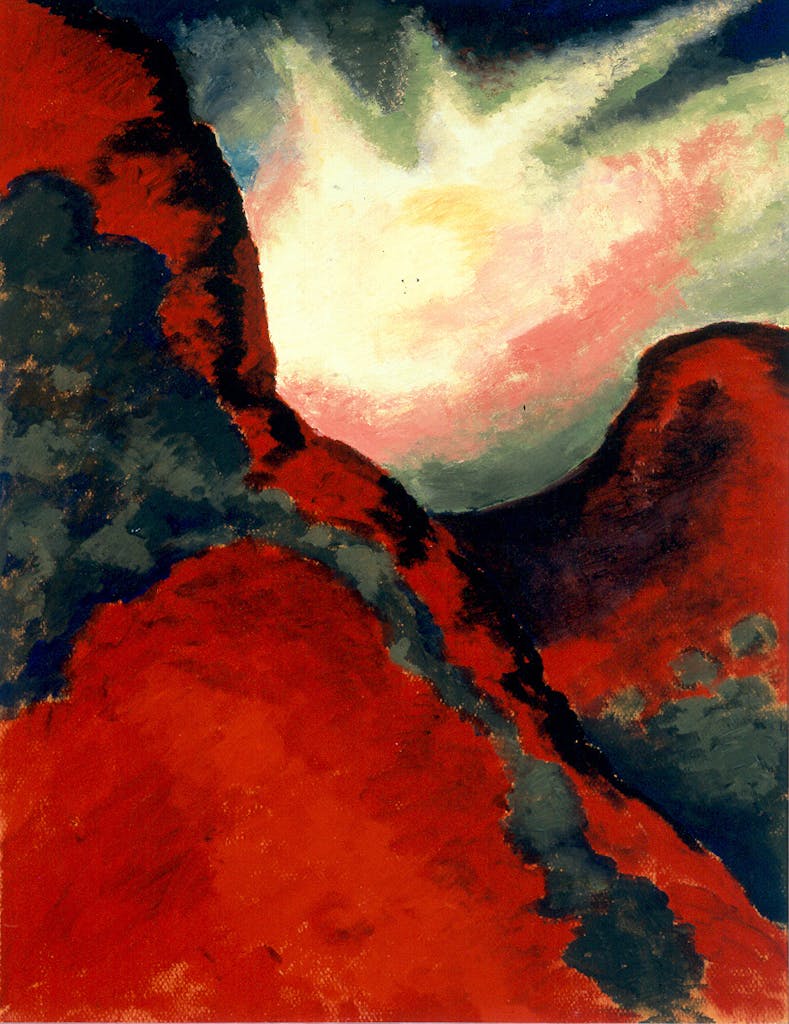

O’Keeffe often painted during the early evening, sitting on the floor of a west-facing porch of the house where she rented the upstairs bedroom. She and her teenage sister Claudia frequently perched on the ledge of the room’s dormer window, gazing out, and they wandered onto the plains at all hours. O’Keeffe was awed by the sight of trains approaching from miles away, the lacy effects of cattle dotted against the sunset, and the “long ribbon line” of the horizon below an infinite sea of stars. Her job also gave her plenty of time to explore Palo Duro Canyon, whose rugged vistas she made her own in works such as the abstract oil painting Red Landscape. It’s an explosive vision: the hills and hoodoo shapes are softer than in real life, infused with blood-red drama under a violently bright sky. “Surely, it represents something bigger than ourselves, life as well as death, creation as well as destruction,” Von Lintel writes in her book’s introduction.

O’Keeffe also looked more intimately inward with nude self-portraits in pink made during her Texas years. “She always worked on the floor or a table, never on an easel—so there are these beautiful pools and plumes in those watercolors that capture the drawing time,” Von Lintel says.

“Georgia O’Keefe, Photographer,” on view through January 17 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, places the artist at mid-career, obsessively honing her compositions in a different way. Curator Lisa Volpe examined some two hundred images from a previously unstudied archive at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico, to reveal how O’Keeffe later used photography as a framing tool. It’s such an intense exercise in looking that you can make a game of sussing out what’s different from one image in a series to the next.

A pair of drawings of Palo Duro Canyon is the only obvious reference to Texas. Still, Volpe says, “Texas is the place where she really gets a sense of light as form, and that’s something that becomes essential in her photographs.” O’Keeffe appreciated art photography; she became Stieglitz’s muse in May 1917, when she surprised him by visiting her first solo show at his Gallery 291 in New York, just before he shut its doors for good. But her own photos were sketches. “Making a large print: absolutely not important to her. Learning to use her camera: absolutely not important to her! That’s why she really liked her Polaroid,” Volpe says. “It was pretty point-and-shoot, easy for her to get the hang of, and she could have her small print immediately.”

The show’s most artful series contains an abstract black rectangle against an adobe wall. It’s a door, actually—the entrance to a salita, or sitting room, at the Abiquiu, New Mexico, property she bought in the late 1940s—transformed into a mysterious form by the intense desert light and shadows. O’Keeffe made 23 paintings and drawings of the salita door from 1946 to 1960. “I’m always trying to paint that door—I never quite get it,” she wrote.

She took most of the show’s photographs ten to twenty years after finishing paintings of the same subjects, Volpe says. “These were subjects that continued to inspire or haunt her.” Even late in her career, O’Keeffe also still drew from techniques she learned at Columbia University Teachers College in New York as a student of the influential composition teacher Arthur Dow. “He’d draw a large landscape on the board and ask his students to choose a section of it—to only record this corner or that corner, in horizontal or vertical. That is essentially reframing, and it’s something O’Keeffe takes with her and does her whole life,” Volpe says. The salita door fixation also suggests O’Keeffe didn’t forget a similar challenge she created as a young teacher in Amarillo, a few years before she went to Canyon. It was a simple exercise in dividing space: draw a square and put a door in it somewhere.

O’Keeffe didn’t land in Texas by accident. Born and raised on a Wisconsin dairy farm, she moved with her family to Williamsburg, Virginia, during high school, but she yearned to experience the Wild West. She came for adventure and also decent pay, at first training to be an art educator. She needed to log classroom time in 1912, and Amarillo’s new public school system was hiring. She landed her first job there as its supervisor of drawing and penmanship.

Amarillo was a city of 10,000 people then, a hub of the cattle industry with three train stations, streetcars, an opera house, and new mansions. For O’Keeffe, who had studied in big Chicago and Virginia as well as New York, the shock wasn’t the city itself, but the everything and nothing around it. Her love affair with light and landscapes began in Amarillo. “That was my country—terrible winds and a wonderful emptiness,” she later wrote. She taught high school students for two years there, returning home in the summers. After finishing her degree she taught briefly at a college in South Carolina, a place she found dreadful. She couldn’t wait to get back to the Panhandle in 1916. The college in Canyon had one fine new building, sixteen faculty members, and more than five hundred students. O’Keeffe was the only art professor at a time when “art” meant pretty much anything that involved drawing, including fashion design and building sets for the college’s plays. But she loved teaching and was fond of her students. “It wasn’t a backup plan,” Von Lintel says.

A kind of twenty-first-century successor to O’Keeffe as a professor of art history and director of the gender studies program at West Texas A&M, Von Lintel grew up in the Midwest and arrived at the university in 2010, before the art department finally began allowing figure studies classes to use live models. The Canyon community is still staunchly conservative, and sometimes at odds with the university’s academics, she says. “If you love it, you love it. And if you don’t, there are probably reasons. . . . One of the things I had to tease apart was people saying [O’Keeffe] hated everyone, and everyone hated her; that she was fired and she left. That is not how it happened. She found her cohort of people that supported her, and that she loved; but she also felt very judged by certain people in Canyon.”

“The little fat woman and I fell out,” she wrote in early 1917, when her landlady refused to let her bring a gentleman up to her room. (She took a three-hour ride in his car instead.) “I hear that I am the most talked of woman on the faculty,” she wrote another time. “I believe I’m considered “queer”—”different.” She stood out in myriad ways: “My clothes—my shoes—my hair—my face—my talk in classes—the things I say.” When the U.S. entered World War I and the trains carrying cattle to market also took away dutiful young soldiers, O’Keeffe brooded, flooded with doubts about the future. Her troubles with the townspeople increased during the winter of 1917–18, after she asked a drugstore proprietor not to sell Christmas cards that mixed an image of Statue of Liberty with verse about wiping Germany off the map. Some folks in town accused her of being unpatriotic. By Valentine’s Day, she was on a train to San Antonio—not to escape but to recuperate, trying to shake a respiratory illness that had dogged her for months. She left in early June for New York and never lived in Texas again, although she visited that football player and his family for years, on her way to New Mexico.

There’s no organized tour, but whiffs of O’Keeffe’s time in Texas still exist in Canyon. The building where she taught, Old Main, has been reconfigured inside, but it’s still there. “You can look out across the prairie seeing what she saw, in a way, including trains coming in from the distance,” Von Lintel says. The Craftsman house where O’Keeffe lived, at 500 Twentieth, still stands; and Hudspeth House, at 1905 Fourth Avenue, where she took her meals, is a bed-and-breakfast. And of course the winds still blow and the vistas still glow at Palo Duro Canyon.

Some of the more than fifty works O’Keeffe produced during her Texas time can be found in museums across the state, although the fragile watercolors are not always on view. Evening Star No. V is in the collection of the McNay Art Museum, as is the fiery 1953 painting From the Plains I, created much later from her memories of the state. The Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum at West Texas A&M owns Red Landscape, and works from O’Keeffe’s Light Coming on the Plains series belong to Fort Worth’s Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

Volpe and Von Lintel both love the Light Coming on the Plains watercolors. “They’re so abstract yet so descriptive,” Von Lintel says. She likes to show them to students and ask what they see in the oval shapes. “They’ll say it looks like an egg, but if you tell them it’s a landscape they see it right away . . . I could show it to anybody who’s grown up on the plains, and they see it.”

CORRECTION: This post has been updated to fix an error—Georgia O’Keeffe couldn’t wait to get back to the Panhandle in 1916, not 2016.