In the early eighties, when I was an undergraduate at the University of Texas at Austin, politics consumed my life. I spent most of my time thinking about politics, covering state politics, or writing editorials about national politics for the Daily Texan, where I served as editor in chief. I was reading about politics too, in newspapers, magazines, and textbooks. And I plowed through countless political novels, most of them variations on the classic film Mr. Smith Goes to Washington—black and white stories about figures who were either wholly good or wholly evil. There was part of me that enjoyed that sort of thing, but even then I had a strong suspicion that the real world of politics was very different. Those books certainly didn’t reflect what I saw going on at the Capitol, just a few blocks south of the Texan’s office.

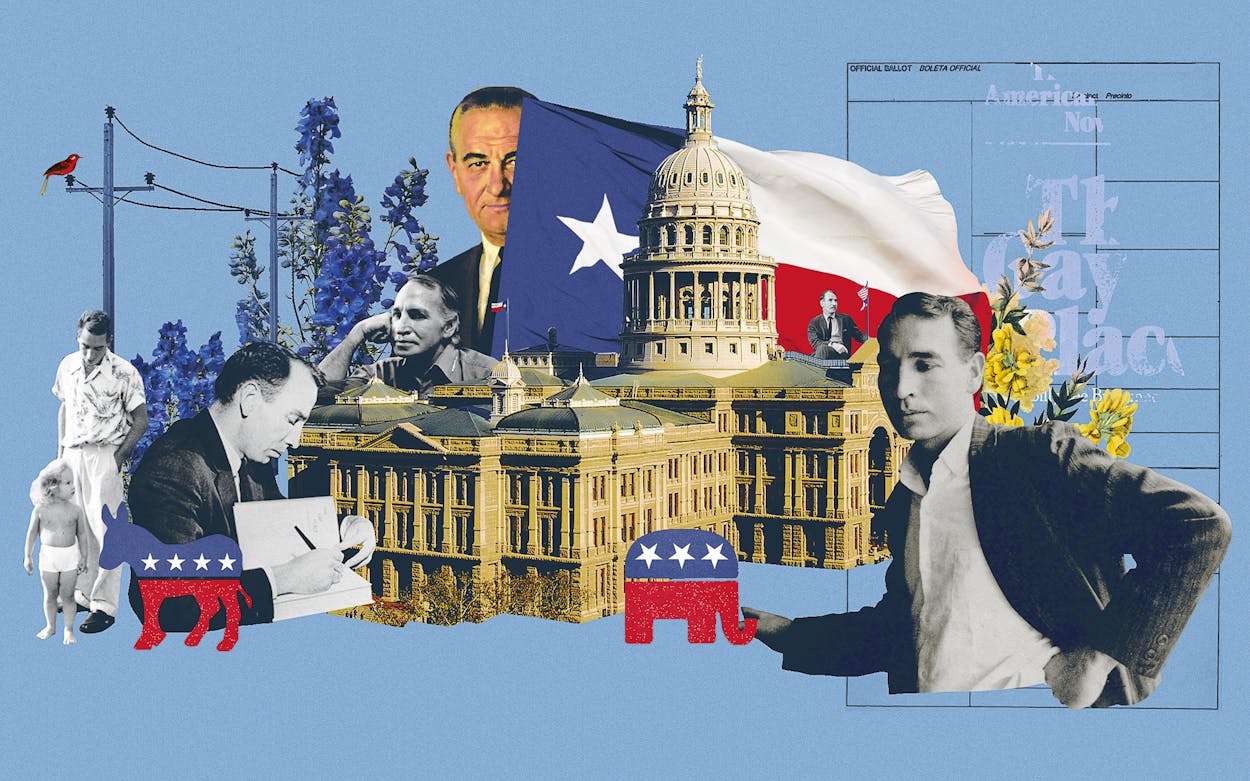

And then I was handed a copy of Billy Lee Brammer’s 1961 novel, The Gay Place, and I finally found what I hadn’t quite realized I was looking for. The Gay Place was the first political novel—more precisely, a series of three linked novellas—I’d read that portrayed politicians as I suspected they really were: flawed human beings possessed of intentions both good and ill and many stations in between. In particular, Brammer’s portrait of the book’s Lyndon Johnson doppelgänger, Arthur Fenstemaker, was a revelation. Fenstemaker was rude, crude, mean, and brilliant, a far more interesting and complicated character than the popular view of Johnson as a warmongering bumpkin that was prevalent then.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that The Gay Place eventually inspired me to stop writing about politics and get into the actual political arena, where I’ve spent virtually my entire adult life. But when I left UT, it initially inspired me to do something else: to write a biography of Brammer. I don’t think I was motivated by some free-floating desire to be an author; more than anything, I just wanted to better get to know Brammer, who died in 1978, before I’d had a chance to meet him. In his wake, he left behind a trail of people in Austin who had crazy stories about him that they were more than happy to share.

I did a respectable amount of research on Brammer, and his family was kind enough to loan me many of his papers, including some unpublished articles and manuscripts, which were a treasure to a fanboy like me. But after a year or so, I gave up on the project. The reasons were many. Partly I was young and didn’t know what I was doing. Partly I was eager to enter the rough-and-tumble world of politics itself, by working on the U.S. Senate campaign of an idealistic young Texas pol named Lloyd Doggett. Partly I had a falling-out with Brammer’s family after I wrote a magazine piece about him that they didn’t like. And partly I had made the unwise decision to try to lead a life much like that of the famously dissolute Brammer: over the course of that year I probably snorted a bathtub full of speed, which made me realize that if you take a little speed you can write a book in a week, but if you take a lot of speed, you can’t write a chapter in a year. I had gotten a sense, firsthand, of why Brammer never managed to write a follow-up to The Gay Place.

Brammer was not only a singular literary talent, he was something of a Zelig-like figure, someone who witnessed seismic changes in American culture, often in the company of figures like Timothy Leary and Janis Joplin.

The nail in the coffin of the project was the day the journalist Nicholas Lemann—then a staffer at this magazine—told me that my project sounded like a long magazine article, not a book.

Thankfully, the literary biographer Tracy Daugherty has proved Lemann wrong—and done what I failed to do 35 years ago. His new book, Leaving the Gay Place: Billy Lee Brammer and the Great Society (UT Press), is a comprehensive and compelling account of a life lived by a unique character against the background of a tumultuous era.

Of course, Daugherty, a Midland native who has written biographies of Donald Barthelme and Joan Didion, had great material to work with. Brammer was not only a singular literary talent, he was something of a Zelig-like figure, someone who witnessed seismic changes in American culture, often in the company of figures like Timothy Leary, Janis Joplin, and a young woman named Diana de Vegh, who Brammer was astonished to learn was sleeping with President John F. Kennedy at the same time that she was bedding down with him. If something important happened during Brammer’s adult life, he most likely witnessed it or knew someone involved in it or had something incisive to say about it.

Brammer, who was born in 1929 and grew up in the Dallas neighborhood of Oak Cliff, spent a great deal of time as a child listening to the radio, which brought news from distant reaches of the world into the lonely confines of his home. “Out there on the wretched edge of Western Civilization,” he wrote in 1973 in Texas Monthly’s second issue, “the ether . . . was turbulent with the babble and burble and atmospheric hiss of much of the Republic’s long suppressed derangements: mental, emotional, musical, or mercantile.” The assembly of “carny pitchmen” and “nostrum promoters” he listened to so attentively seems to have made an impression on him. Much of his writing serves a similar function to that of radio in its infancy, transmitting a peculiarly American sort of insanity to a broad public.

Brammer’s father’s job as a construction superintendent helping to electrify rural Texas doubtless had an effect on him too. Witnessing the introduction of interior lighting and modern conveniences to the countryside—courtesy of Lyndon Johnson, then an enterprising young congressman—gave him a sense, early on, that big social changes were happening around him. It was a source of no small frustration that he felt far removed from most of them.

Eventually, the profession of journalism helped him get in touch with those forces. Brammer found his way to the vocation of reporting first through the campus newspaper at what is now the University of North Texas, then the Corpus Christi Caller-Times, the Austin American-Statesman, and the progressive Texas Observer.

It was that last gig that, improbably, led him to accept a job in 1955 on Lyndon Johnson’s Senate staff in Washington, D.C. At the time, Johnson was increasingly positioning himself to the right of much of the Democratic party, in order to further his national ambitions. That drew the ire of progressive Texas Democrats, who expressed their views in the pages of the Observer. Johnson hoped that having Brammer on his Senate staff would relieve the heat he was feeling from liberals. As for Brammer, he had been fascinated by Johnson since LBJ’s second Senate campaign, in 1948. “For sheer drama, the guy was hard to beat, a folkloric figure,” Daugherty writes.

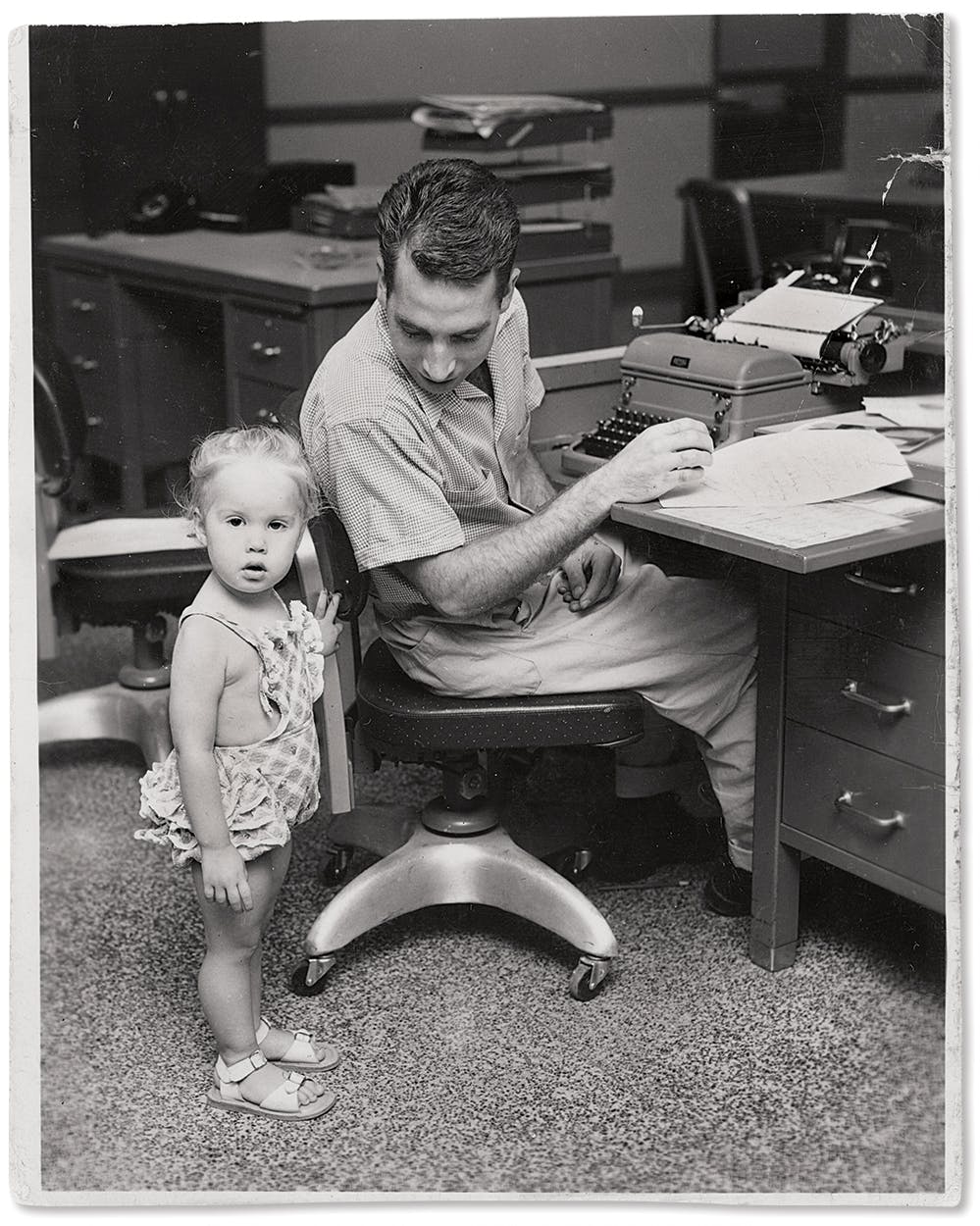

D.C. is where Brammer the great novelist came of age. By day he cranked out speeches, congressional record statements, and letters to LBJ’s mother that she apparently believed were authored by her son. By night, fueled by what had become a steady diet of amphetamines, he wrote drafts of a novel he was then calling “The Heavy-Honeyed Air,” about a governor who bore a striking resemblance to Brammer’s employer. When the book, eventually renamed The Gay Place, was published in 1961, it received rave reviews.

Which wasn’t just good news for Brammer but, as Daugherty points out, great news for a generation of Texas writers who believed that Brammer had finally made it possible for them to be taken seriously, and for Texas itself to be regarded as a subject worthy of literary exploration. (Larry McMurtry’s debut novel, Horseman, Pass By, published that same year, doubtless helped in both regards.)

Brammer and Johnson

“Brammer would feed Johnson a line, and LBJ would turn his bulk on him and shout, ‘Who are you?’ ‘A nameless sycophant of no importance,’ Brammer answered. Johnson would roar.” —from Leaving the Gay Place

“This is a requiem for a man who could have been [Texas’s] Faulkner or [Joyce],” Texas Monthly founding editor William Broyles wrote in these pages in a 1978 remembrance of Brammer. Daugherty quotes the essay at length: “When I read The Gay Place . . . I was in college in Texas . . . and neither my professors nor my fellow students considered our own state worthy of study. We spent entire semesters, however, on the politics of Massachusetts mill towns or the literature of the English countryside, as if politics and literature were phenomena that always cropped up elsewhere. The Gay Place changed all that for me, and I stayed in Texas because of it.”

And then, in a sad decline that Daugherty chronicles in unsparing detail, Brammer never followed up on his one great success. Two years after the book’s appearance, rather than preparing a second novel for publication, he was bouncing from job to job, failing to complete writing projects, and was frequently unable to pay bills or child support. (He was even a founding staffer at this magazine, having been hired by his loyal fan Bill Broyles.) He died at the age of 48 of a speed overdose.

It’s not clear how much Brammer’s inability to write another book haunted him, but it has certainly stuck with many of us, who can only dream about what sorts of books a slightly less self-destructive figure might have gifted us with. Yet we shouldn’t allow that disappointment to overshadow the significance of Brammer’s single towering achievement. One of the most valuable accomplishments of Daugherty’s biography is that it makes clear that The Gay Place, which is often thought of as the book that put Texas literature on the map, is something more than that: it’s not just a Great Texas Novel but a Great American Novel, as worthy of a place in the literary firmament as such contemporaries as To Kill a Mockingbird, Catch-22, and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

In fact, I would argue that it’s the Great American Political Novel, more psychologically nuanced than Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men, truer to life than Allen Drury’s Advise and Consent, less cartoonish than Charles W. Bailey II and Fletcher Knebel’s Seven Days in May. I’ve spent the past four decades of my life immersed in politics, and even now, many years after I first had my head turned around by Brammer’s masterpiece, hardly a day goes by that I don’t hear about some recent outrage or oddity that makes me think, “Yeah, that’s like something straight out of The Gay Place.”

Mark McKinnon is a veteran political operative who worked for Governor Ann Richards, President George W. Bush, and Senator John McCain. He is the executive producer, creator, and co-host of the Showtime series The Circus: Inside the Wildest Political Show on Earth.

This article originally appeared in the November 2018 issue of Texas Monthly. Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Books