Featured in the San Antonio City Guide

Discover the best things to eat, drink, and do in San Antonio with our expertly curated city guides. Explore the San Antonio City Guide

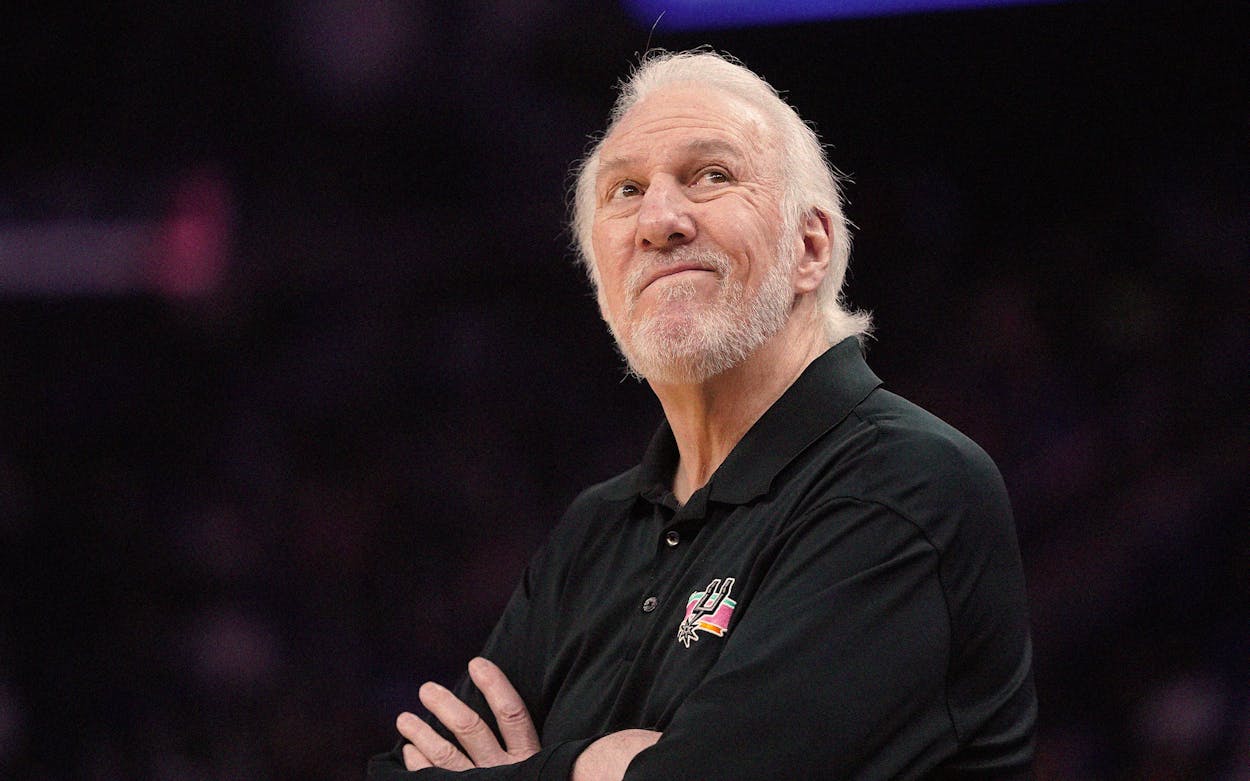

Tim Duncan was nearing the end of his Basketball Hall of Fame induction speech last May when the moment that nearly everyone in the audience had been waiting for arrived. Having paid respects to his family and teammates, coaches and trainers, having spoken of his love for the San Antonio Spurs, his famously stoic voice cracking at times, Duncan could avoid a certain topic no longer.

“Pop!” someone yelled from the audience. Duncan paused and laughed as he looked toward the front row, where Spurs coach Gregg Popovich sat, his emotions hidden behind a surgical mask.

“I don’t want to talk about him,” Duncan said. “He’s gonna get mad at me if I talk about him.”

This time, though, he would defy the only coach he’d had over nineteen NBA seasons, through five championships and a career in which the Spurs never missed the playoffs and became the NBA’s standard for professionalism, consistency, and success. Duncan and Popovich developed complete trust in each other over the years, and their relationship became the cornerstone for everything the Spurs have come to represent in Texas and beyond.

“The standard you set,” Duncan began. “You showed up after I got drafted [in 1997]. You came to my island [in the U.S. Virgin Islands]. You sat with my friends, my family. You talked with my dad. I thought that was normal. It’s not.

“You are an exceptional person. Thank you for teaching me about basketball. But even beyond that, teaching me that it’s not all about basketball. It’s about what’s happening in the world; about your family. Just—for everything. Thank you for being the amazing human being that you are.”

With that handful of words, Duncan had said what hundreds of NBA players, coaches, executives, fans, and others in all sorts of leadership positions around the globe know to be true.

Even those outside Gregg Popovich’s fortresslike circle of trust admire him from afar, because they’ve seen the respect and admiration he garners among those who’ve worked with him, played for him, or simply encountered him along the way.

They know that this brilliant, funny, frequently hotheaded, and easily annoyed man who wears outrage at reporters’ questions like a badge of honor and cries foul at politicians and their demagoguery is an extraordinary leader and a brilliant, caring human being.

He coaches players hard, demands plenty, and is almost never happy. Virtually every San Antonio player has memories of Popovich’s in-game blowups after failing to hustle back on defense or throwing a lazy pass. At the same time, they know he cares deeply about them in ways that many coaches can’t or won’t. They know, too, that Popovich is a brilliant basketball man who wants them to understand the world beyond the arenas and the insulated NBA bubble (no, not that bubble). He’s famous for chewing out a player in practice, then inviting him to dinner that evening to discuss, say, infrastructure or health care. His impact in moments like that is impossible to measure.

“I was young, pretty selfish, insecure and all the stuff,” Phoenix Suns coach Monty Williams told the Arizona Republic of his two-plus seasons playing for Popovich. “It was weird to get yelled at in practice and then get a call later on and get invited to dinner. It was like, he just yelled at me about three hours ago. I wasn’t used to that and then I figured it out, how much he cared about me as a person.”

Williams said one of the veteran Spurs explained it like this: “Mont, you don’t get it. He cares about you. He can see it in you.”

Williams eventually did get it. “He gave me a chance to see the world from different lenses,” Williams said, “and I think, as a young basketball player, I was always looking at [my] next contract, minutes, and he made me look at it differently.”

“Selfless, egoless basketball,” Williams added. “Serving your teammate. Working your tail off. Having a broader view that’s bigger than basketball. . . . That culture meant more to me than probably any culture in my life outside of high school.”

Popovich told the newspaper: “The arm around Monty and sticking it to him in practice, both have to be there or we wouldn’t be as close as we are today.”

San Antonio team dinners—in Michelin-starred restaurants, with Popovich, an avid oenophile, studying wine lists, demanding guests try this one or that one—are the stuff of legend.

“What’s my legacy?” he once told a reporter. “Food and wine. This is just a job.” These days, Popovich, 73, in his twenty-sixth season as the Spurs head coach, is being forced to do the very thing he hates, the thing he constantly preaches against: celebrate himself.

He’s the first coach in NBA history to win 1,500 total games (now 1,502 regular-season and playoff contests combined). The Charlotte Hornets, who entered the NBA as an expansion team eight years before Popovich became San Antonio’s head coach, trail him by 390 victories. And sometime after the upcoming NBA All-Star break, Popovich is a shoo-in to set a new league record for regular-season wins. At the moment, with 1,332 victories, he’s tied with Lenny Wilkens and three behind the all-time leader, Don Nelson.

Popovich has reminded reporters that he owes his success to hundreds of others, beginning with a pair of Hall of Famers, Duncan and David Robinson. If anyone tries to give him too much credit, he’ll tell them to get a clue, only he won’t phrase it exactly that way. But as former Miami Heat great Dwyane Wade put it: “What makes a great coach is getting a lot of young men and helping them become men. Adding to their life. Coach Pop has done an amazing job of helping young men become grown-ass men.”

Besides shepherding those five NBA championships, Popovich was the head coach when Team USA won gold at the Tokyo 2020 Olympics. Perhaps because of his background at the U.S. Air Force Academy followed by a stint of active duty as an intelligence officer, winning that final game in Japan prompted tears.

“It’s like the best feeling I’ve ever had in basketball,” he told his players.

Several NBA insiders had speculated that Popovich might retire after last summer’s Tokyo Games—a rumor that his refusal to deny only seemed to encourage. After all, not only had he appeared to fill in the final line of his résumé with Olympic gold, but Popovich would also be returning to a Spurs team that was beginning a massive, uncertain rebuild after the departures of LaMarcus Aldridge, Patty Mills, DeMar DeRozan, Rudy Gay, and others.

Yet Popovich seemed energized by the challenge—the NBA’s oldest coach trying to compete with one of its youngest rosters. He promised he’d be able to adjust his expectations and that he could measure success by effort and progress in addition to wins and losses. He promised to play fast and keep the Spurs’ offensive and defensive schemes simple. He has also found he loves the challenge of helping players like nineteen-year-old Joshua Primo, who was born during Popovich’s seventh season as head coach in San Antonio.

Even as the losses pile up for the 22–36 Spurs, Popovich has emphasized development over the bottom line. Never mind that the Spurs will likely miss the playoffs for a third straight year (after 22 consecutive postseason appearances). Popovich says his job this season is to help Dejounte Murray, Keldon Johnson, and Devin Vassell become the best NBA players they can be.

But for many around the league, it’s nearly impossible to imagine Popovich embracing a season in which the playoffs and championship contention are not realistic goals. Aldridge, the Dallas native and former Spurs center, was so concerned about his former coach’s ability to handle losing that he called Popovich last summer, according to the San Antonio Express News.

“Pop,” Aldridge asked, “how are you going to do it?” Popovich summed it up this way: “You have to put away what was and what could have been had we kept everyone together.”

His temper still lights up a huddle now and then, but for the most part, the coach has remained focused on the big picture. “The most important thing to develop is that competitiveness and that drive and what wins and what loses,” he said.

Mills, who played ten seasons for Popovich before signing with the Brooklyn Nets last summer, told the newspaper: “I’m impressed about how you go from winning so much and then being able to take that winning culture and all the values that come with it, and teach it and hand it off to the young boys to try to create that again. Obviously, it’s not easy, but the time and effort that’s put into something like that is what makes this place so great in the first place.”

Mills was so nervous about informing Popovich of his decision to leave for Brooklyn that he began with a middle-of-the-night text message. Popovich responded quickly, telling Mills he understood and that he loved him.

These days, Popovich reserves his most passionate outbursts for issues and antagonists away from basketball, such as former president Donald Trump, whom Popovich called a “soulless coward” and “deranged idiot,” among other things. He has blasted the U.S. Senate for not passing voting rights legislation and recently criticized a San Antonio–area school district for continuing to honor Christopher Columbus.

Popovich asked rookie Jock Landale, who is from Australia, to do a team presentation on the bipartisan infrastructure bill that President Joe Biden signed into law last year.

“It’s not just basketball with him,” Landale said. “I had to actually come in with a presentation and talk to the group about it and educate them on what was going on.” He added: “He’s always quizzing us about real issues in the world. Just trying to really broaden our knowledge on things greater than basketball and that’s kind of cool to see from a guy of his stature.”

Popovich is so respected throughout the NBA that few thought it odd when Minnesota Timberwolves guard Patrick Beverley approached him to chat during a recent game. “Pop is so good that he coaches both teams,” a television announcer gushed.

His in-game television interviews can be wickedly funny and borderline hostile, given his refusal to play the traditional sound-bite game. “Happy? Happy?” he asked during one 2012 game. “ ‘Happy’ is not a word that we think about in the game. . . . We’re in the middle of a contest; nobody’s happy.”

Watch enough of those interviews, and what comes through is that Popovich is having fun with the whole ritual. He understands—and won’t play along with—the stagecraft. At times he can even be heard whispering “I love you” as he pats the interviewer on the back and returns to his team. His give-and-take with the late Craig Sager of TNT became must-watch television. Was he really that annoyed at a guy simply doing his job? He wasn’t.

As Sager’s bout with cancer became public, Popovich checked on him regularly through telephone calls and notes. “Craig . . . we want your fanny back on the court,” he told Craig Sager Jr., who briefly substituted for his dad, during one game. “I promise I’ll be nice.” When Sager did return, Popovich opened the interview this way: “I can honestly tell you this is the first time I’ve enjoyed doing this ridiculous interview we’re required to do, and it’s ’cause you’re here and you’re back with us. Now ask me a couple of inane questions.”

Inane questions are one of his favorite topics. Once, during a postgame news conference, a reporter asked if Popovich regretted not going with a smaller lineup earlier in the game. “No,” the coach said. “You coaching now? You should try not to do that.”

Those who’ve worked or played for Popovich carry deep reservoirs of loyalty. His circle of trust is small but unbreakable. And that loyalty cuts both ways. When he brought retired Spurs great Manu Ginóbili back to the organization last year, he was asked what role he envisioned for the Argentine Hall of Famer.

“He’s going to do everything,” Popovich said. “[He’s going to] see where he feels comfortable. It’s just great to have him in the program for all kinds of reasons, but mainly because we love the guy.”

As Golden State Warriors coach Steve Kerr, who played four of his last five NBA seasons in San Antonio, said: “I’ve learned so much, not just about the game, but about people, about culture. And so a lot of what we do here in Golden State is based on what I learned from Pop.”

Becky Hammon joined the circle after Popovich made her the NBA’s first full-time female assistant coach. She’s now the head coach of the WNBA Las Vegas Aces. “I’m especially thankful to Pop, who only cared about my potential, not my gender,” she said. “He saw something special in me and was willing to invest the time and energy to help teach and develop a young coach.”

Now that Popovich is in his seventies and the Spurs appear to be several years away from returning to title contention, speculation about the coach’s retirement clatters behind him like a string of tin cans. None of it comes from Popovich himself, except in his refusal to speculate. Some of those who know him best aren’t sure if he has even considered walking away from the game.

When Erin Popovich, his wife of four decades, died in 2018, the coach soon returned to work and began pouring himself into his job. The challenge in front of him—this new batch of Spurs—may have come at the right time in his life. “I never got too excited about the winning and I never got too down about any losses,” Popovich once said. “You’d rather win than lose, but it was never really the priority in how you lived your life or conducted yourself. We enjoyed the teaching, the camaraderie as much as anything. The airplanes, the buses, being with a great group of guys.”

“How can you complain when you were able to draft Tim Duncan first?” he said on another occasion. “And we have three decades of winning and playing that way. Well, that can’t last forever. But with that kind of good fortune, you shut your mouth, don’t cry and move on.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Spurs

- NBA

- San Antonio