Since he was a child, Tomás Q. Morín has counted. He has calculated the seconds between breaths, the number of telephone poles on a given street, and, once, even “the soft-blue stripes of a man’s shirt.” The mental tallying was a strategy for dealing with the traumatic situations of his youth. At age four or five, he witnessed his father shooting heroin. “I was impressed the first time I watched him cooking,” Morín writes in his debut memoir, Let Me Count the Ways, which hit bookstores in March. “Who knew a spoon and a bit of cotton was all anyone needed to make some magic happen?” He was still a child when he became a caretaker for his father, who oscillated for years between withdrawal and relapse. When Morín’s mother later separated from his father, she began dating a man who physically abused her in their home. In times of crises like these, Morín turned to counting anything and everything to give him a sense of control, which eventually led to the development of his obsessive-compulsive disorder.

As a young boy, Morín dreamed of the day when he would leave his hometown of Mathis, about thirty minutes northwest of Corpus Christi. A neighbor named Jackie, who was in and out of jail and also suffered from a drug addiction, became an unlikely role model for Morín and pushed him to prioritize school and to consider writing as a career. Jackie became his “surrogate father,” encouraging him to succeed throughout his teen years while providing a healing example of fatherhood and masculinity.

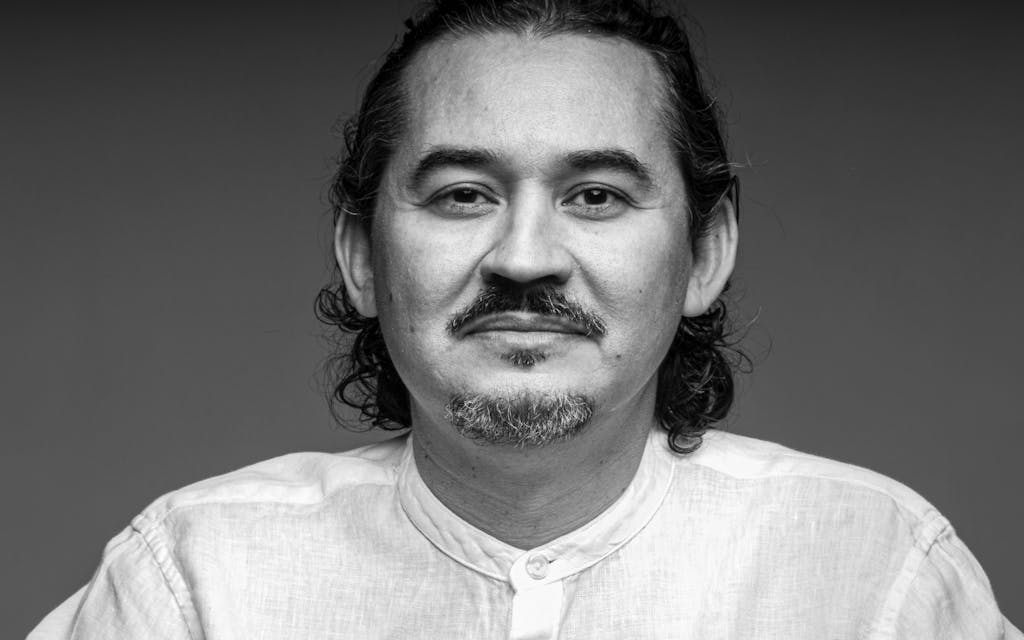

After high school, Morín studied Spanish at Texas State University and John Hopkins University, but he found his true passion in poetry. He returned to Texas State, where he earned an MFA in creative writing, and is currently an assistant professor at Rice University. His first collection of poems, A Larger Country, was the winner of the American Poetry Review/Honickman First Book Prize, and in April, Morín won a 2022 Guggenheim fellowship.

In Let Me Count the Ways, Morín recounts his childhood with wry, dark humor and examines the abuse, trauma, and his coping strategies. But, more than anything, he focuses on the men in his life and grapples with conflicting models of masculinity. Morín spoke with Texas Monthly about the book, his Guggenheim award, and what being a father means for him.

Texas Monthly: Let Me Count the Ways is probably the most intimate glimpse into your life out of all of your works so far. Why did you decide to write the memoir?

Tomás Morín: A lot of these scenes and moments in the memoir were stories that I would tell my friends. There came a point when I realized that my memories of those events were starting to shift. It’s just the nature of memory. I wanted to be able to preserve the memories of my father, my grandfather, and Jackie. They’ve all passed away now, but I felt like in the stories that I would share with people that they were alive again. I thought that if I could write well enough, summon enough skill, and get them and their stories and my relationship to them into this book, then as I grow older, and I get farther and farther away in time from those moments in my life, I’ll still be able to return to the pages and find them.

TM: You recently had your first child. How did fatherhood influence your decision to write the memoir?

Morín: My son will one day be able to read this book and learn about his grandfather, whom he never knew. He passed away before he was born. And he’ll read about my grandfather. These men were just so crucial in making me who I am—sometimes in positive ways, sometimes in negative ways.

TM: You write about some of those “negative ways” in your book. How did you cope with seeing your loved ones struggling with addiction, incarceration, and abuse?

Morín: I couldn’t change the big picture. I had no power over my father or his addiction. But what I could and did have power over was how I observed and how I marked space—counting, remembering exact details. That was a way to cope. That’s how you can control what you can’t control.

TM: Speaking of marking space, I felt like locations and the geography of Texas were highlighted throughout the book. Sometimes the descriptions of Texas weren’t very flattering. What is your relationship to the state?

Morín: My family has been here in Texas since before it was the United States. It’s home. It’s like what James Baldwin says about the United States. He loves the United States, and it’s that love that allows him to critique it and examine it. I’ve lived in Lubbock, Austin, and San Marcos. I grew up near Corpus Christi, and now I’m living in Houston.

My relationship to the state is definitely complicated. I think a lot of that has to do with growing up with not a whole lot of money or medical resources and seeing other people like me, other Latinos, struggle like my family. And at the same time, seeing all the resources geared toward people who look different than us. It’s hard.

TM: In the book, there is an emphasis on the importance of names. Why is that?

Morín: The Latino community has such a love for wordplay. There’s so much power in a name. When someone adds an “h” to my first name, I bristle. I don’t know who “Thomas” is. There’s no “Thomas” here.

TM: What did you name your son?

Morín: Jack. He’s named after Jackie. In addition to his last name, he has three names. His full name is actually Jack Antonio Francis Morín. The “Antonio” is because my partner loves Antonio Gramsci’s work. “Francis” is because we both love the nickname “Paco,” which comes from Francisco.

TM: How did the act of writing this memoir and reflecting on your memories of your father and Jackie shape your understanding of what it means to be a dad?

Morín: In certain ways, I feel like I didn’t really have a childhood. I became a caretaker for my father and had to navigate the police, health-care workers, and his addiction. I was always going back and forth between being a kid and trying to be an adult. There are moments, as a father now, where I feel my father rise up. In a way, I feel like I’m unlearning the ways in which I was parented.

With Jackie, like right from the start, I realized, “Oh, someone can be a parent and still not be perfect.” They can even use drugs and still love you and be affectionate toward you. He would put his hand on my shoulder or my hair. He would say he loved me and was proud of me. That gentleness and not just loving someone but actually showing it made such a huge impression on me.

TM: You were just awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. What do you plan to work on next?

Morín: I’m working on a new collection of poems. The tentative title is “My Favorite Things,” and it’s going to be in conversation with John Coltrane’s album with the same name. For three books now, I’ve been exploring suffering and trauma, and how we survive that. I feel like I’m ready to explore how we thrive when we are in a state of crisis—not just survive anymore.

- More About:

- Books