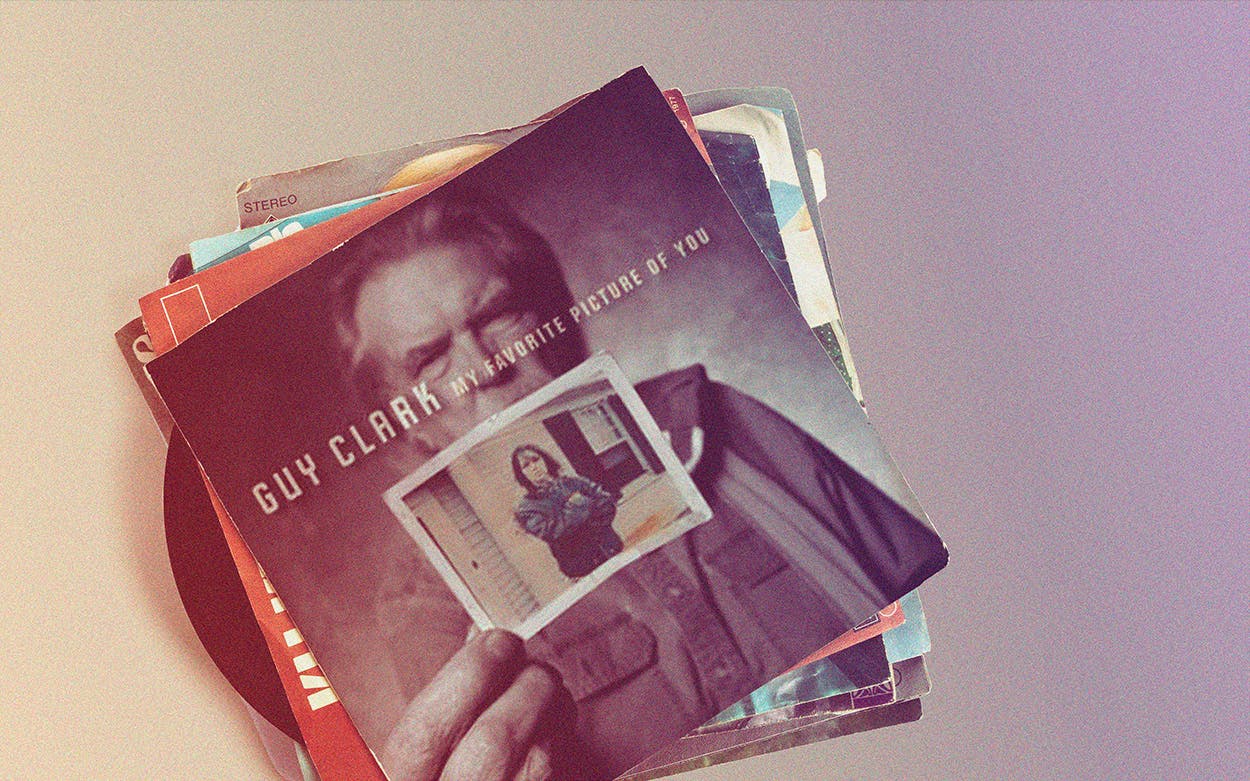

Last week, on the Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, Willie Nelson performed the late Guy Clark’s “My Favorite Picture of You.” Nelson has called it “maybe my favorite song” on his new album, Ride Me Back Home.

The tune was inspired by a forty-year-old Polaroid of Clark’s livid, arms-folded, denim-clad wife, Susanna. It was the thematic centerpiece of an album of the same name, one the then-ailing Clark knew would be his studio swan song. (And one that would claim 2014’s Grammy for best folk album.) Its lyrics portray a dying man meditating on the ghost of the love of his life and the persistence of their love, despite all the obstacles he tossed in its path over the years:

“Oh and you were so angry / It’s hard to believe / We were lovers at all / There’s a fire in your eyes / You’ve got your heart on your sleeve / A curse on your lips but all I can see / Is beautiful.”

There’s much more to the story behind that photograph. I know because I spoke with the man who took it—or at least the man who’s been told he took it by someone who would have known. His name is John Lomax III, a longtime friend of Guy Clark from Houston. He also happens to be my father.

Dad, my late mother Julia “Bidy” Taylor, and Clark had run in the same rowdy circles of the late-1960s Houston folk music scene, and they all moved to Nashville in the early ’70s, alongside Rodney Crowell, Townes Van Zandt, Richard Dobson, and, a little later, Steve Earle.

It was, to put it mildly, a creatively charged environment. After many a night closing down Bishop’s Pub on Nashville’s West End Avenue, these musicians would congregate over whiskey, cheap beer, and vodka in living rooms illuminated by oil-burning lanterns and fragrant with smoke—both legal Marlboro reds and unsanctioned Panama Red. There they’d pass around their guitars and share rough drafts of their latest creations, lay into fiery renditions of their own older songs, or perform hoary old classics by the likes of Hank Williams, Bob Wills, Jimmie Rodgers, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Mance Lipscomb—none of the young Texans aware that many in their crowd were legends in the making.

Luckily, some of these evenings were captured on film, as in this clip from Heartworn Highways, James Szalapski’s 1981 documentary about this wing of the nascent Outlaw Country movement. The setting was Guy and Susanna’s lake house in Mount Juliet, Tennessee, just outside of Nashville, which hosted many such a pickin’ party, as they were called in those days:

It was the morning after another of these nights when Dad took Guy Clark’s favorite picture of Susanna. Or so he’s been told: “Guy was the one who swore up and down that I took it, and who’s going to argue with Guy Clark on something like that?”

Dad’s memory of the event is foggy, for good reason. Unlike today, when pictures are instantly disseminated online and stored on computers or in the cloud, this was truly a snapshot of a moment in time. Only one copy of it ever existed, and seconds after Dad took the picture, it was gone from his life, if forever treasured in Clark’s heart. As the song puts it:

“My favorite picture of you / Is the one where you’re staring / Straight into the lens / It’s just a Polaroid shot / Someone took on the spot / No beginning no end / It’s just a moment in time / You can’t have back / You never left but your bags were packed / Just in case.”

Dad knows it was Polaroid and that it would have been taken early in ’74. He believes it was shot at a house on the corner of 21st Avenue South and Portland Avenue, now the site of the Nashville Periodontal Group and then the first of two Nashville homes where my parents tried and failed to hold their shaky marriage together. “There would be picking going on all night, and because I had to work in the morning, I would retire to the back bedroom, and Bidy and the pickers would carry on all night long,” he said.

Sometimes, he’d be heading out the door for work while the last dying embers of the previous night’s party were still smoldering. He thinks that was the case here—and that he happened to have his Polaroid camera out for some other reason when an upset Susanna rolled up in the morning to collect her carousing husband. Dad must have pointed the camera and clicked, waited for the picture to pop out, shook it to hasten its development, and then maybe giggled over the still-warm snapshot with Guy and a perhaps slightly mollified Susanna.

“Yeah, Susanna was clearly not pleased with the events that gave rise to Guy’s demeanor that morning,” Dad said, adding with a laugh, “Maybe because she wasn’t in on the party. I don’t know.”

Dad never knew how deeply Clark had treasured that photo—through the years of his tumultuous marriage to Susanna, her physical decline and agonizing demise, and his final years as a widower. Hearing of its resurrection was a puzzler to Dad, a bit like winning a contest you had no recollection of entering and weren’t positive you deserved to win.

“When they told me they were putting it on the album cover, I just thought, ‘Oh, great. Too cool!’” he said. “[But] I have no way of proving or disproving that I took the picture, because it’s a Polaroid, so that would be the only copy.’”

Yep, just a Polaroid somebody took of a clenched-fisted woman, “not gone but going, just a stand-up angel who won’t back down, nobody’s fool, nobody’s clown.” But now Susanna is gone, and so is Guy. Yet thanks to Clark’s gift and Nelson’s appreciation of it, that moment in time will live on for as long as Texans sing songs.

- More About:

- Music

- Willie Nelson

- Guy Clark