Elizabeth Olsen pulls into my carport driving a wood-trimmed Oldsmobile Vista Cruiser. She lets it idle a moment, the wagon’s engine rattling like rusty chains inside a paint can, before she finally puts it out of its misery. When she steps out of the car, she is stained with blood.

Olsen looks down at her crimson blouse. Whatever emotions may be playing across her face right now, they’re difficult to read from behind the phalanx of crew members crowding my patio. My line of sight is further obscured by the camera dolly running across the spot where my fence once stood. The subtle nuances of Olsen’s performance will surely enthrall the viewers of HBO Max’s Love & Death when the show premieres on April 27, 2023. But right now it’s October 2021, and I’ve been watching her run this scene for close to an hour.

After an appropriately dramatic beat, Olsen turns and heads for my back door. Well, not my door. That was hauled off weeks ago, along with the fence and most of our furniture. The door’s replacement is a late-seventies model, painted in screaming burnt orange.

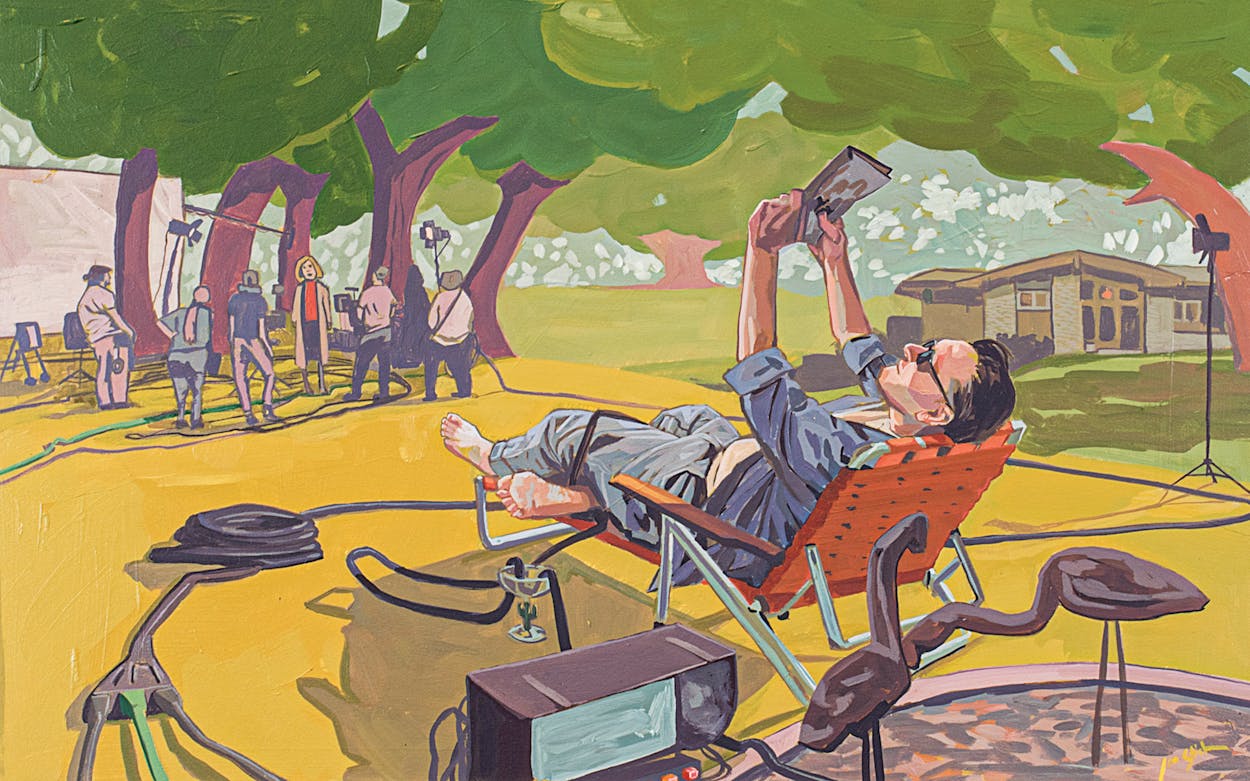

When my wife and I agreed to let Love & Death film at our house, we gave its producers permission to make any changes necessary in the name of authenticity. The crew arrived armed with power tools and paintbrushes. Our daughters’ cedar play set was dismantled with unnerving speed, replaced by one made of old-fashioned, thigh-searing metal. The workers swapped out the window shades for thick polyester drapes the color of mashed yams, replaced our chandelier with a paper lantern, and painted the walls a truly hideous harvest gold. The house’s bones were the same, but it wasn’t really ours anymore. It was a ghost torn between worlds, haunted by tragedy and earth tones.

Love & Death takes place in and around 1980, the year that Candy Montgomery, a homemaker living in Wylie, just northeast of Dallas, killed her friend Betty Gore, striking her forty-plus times with an axe in the grisly denouement to Candy’s affair with Betty’s husband, Allan. It’s a harrowing but compelling true story that was unforgettably told in the January and February 1984 issues of this very magazine by writers Jim Atkinson and John Bloom and in their book released the same year, Evidence of Love. (That HBO Max picked our house to film a show based on a Texas Monthly story—and that the magazine, for which I’m a writer-at-large, happened to be executive producing—was a fateful twist that proved confusing to just about everyone involved.)

Candy’s tale had been adapted for television twice already. But Love & Death distinguishes itself immediately through its deep bench of talent. In addition to Olsen as Candy, the cast includes Jesse Plemons and Lily Rabe as Allan and Betty Gore; Patrick Fugit as Candy’s husband, Pat; and Krysten Ritter, wearing a reddish wig, as Candy’s confidante, Sherry Cleckler. The miniseries is executive produced by the Big Little Lies team of Nicole Kidman and David E. Kelley, and directing duties are split between Dallas native Lesli Linka Glatter (Mad Men, Homeland) and The Wire’s Clark Johnson. This is one of those prestigious, appointment-television shows that arrives with Emmy gold in its eyes. Every detail has been fussed over, down to the doorknobs.

Olsen stumbles through my doorway now, tripping over the threshold with a precision she’s honed over several takes. The camera glides back to starting position. A stunt driver hustles to the car, bringing it to belching life. I crane to see underneath, wondering if its LBJ-era oil pan is leaving my carport looking like Olsen’s shirt.

I spy Marissa Lovely, the assistant location manager, walking in my direction. All of our faces are hidden behind KN95 masks—we’re still deep in the pandemic—yet Marissa has an uncanny ability to pick up on the slightest furrow of my eyebrows. As our liaison throughout the shoot, Marissa has been tasked with assuring me repeatedly that our house will survive. “I promise,” she’s fond of saying, “it’ll be like we were never here.”

Marissa is completely sincere, and she manages a top-notch crew, but even then I know that our house just won’t be the same. They’ll bring back our doors and our fence, and they’ll return our home safely to the twenty-first century, but there will be traces left behind that won’t be so easily scrubbed out.

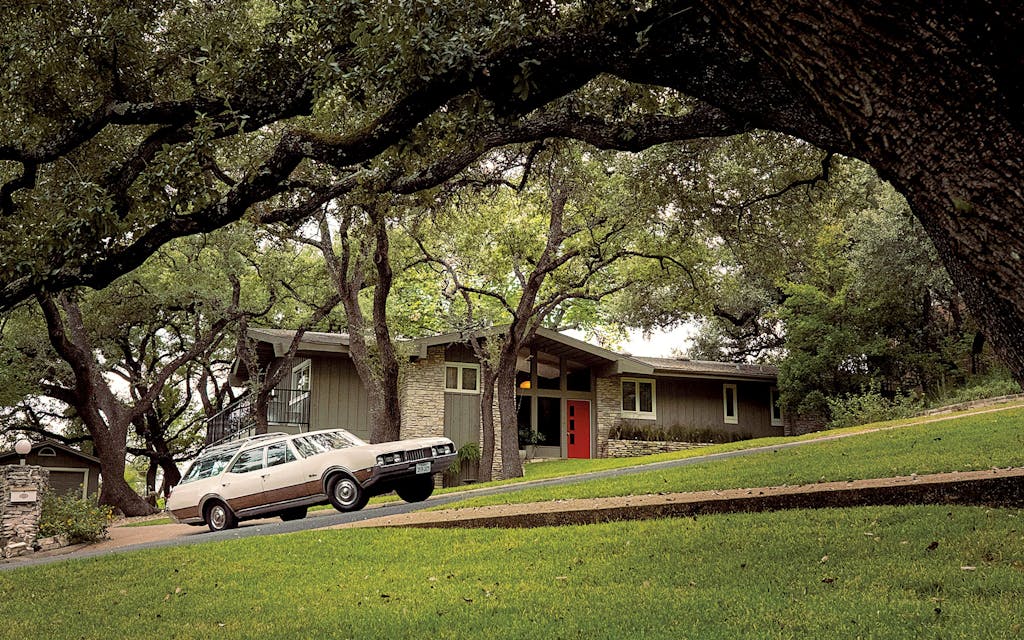

Having your home star in a TV show is, I imagine, a bit like owning a racehorse. People are impressed. Sometimes they congratulate you. But really, the house does all the work. We just happened to be living inside it when a scout drove through Austin’s Northwest Hills, looking for a neighborhood that could stand in for Dallas-area exurbs in Collin County and for a house that could serve as Candy Montgomery’s.

In their Texas Monthly story, “Love and Death in Silicon Prairie,” Bloom and Atkinson were spot-on in describing the Montgomery residence, which still stands, as “sitting on a little knoll, shrouded by two or three red oaks. It was like a contemporary cathedral in wood and glass, with the stylishly unfinished look of a Colorado ski lodge.” Our home indeed sits on a hill. Oak trees—live oaks, but close enough for TV—dot the yard. Its front windows are unusually tall, framed by distinctive woodwork cresting in a peak that I suppose could be described as ski lodge–esque. More important, I’m told, our house has it. Later I would hear that when Glatter was shown a photo, she exclaimed, “Action!”

The path to stardom for a house is surprisingly short. My wife, Keaton, found a note written on HBO Max letterhead pinned to our front door. She called immediately. After a year-plus of COVID restrictions, we needed some stories to tell, she declared. An hour later, a location manager was in our house, photographing the rooms while we pressed him for details.

I recognized the name of the show right away. “No one’s getting murdered here, right?” I asked. Staged or no, I didn’t want those kinds of psychic scars lingering, to look at our kitchen tile and always see traces of Betty Gore’s blood. He reassured us that we’d only be the killer’s house. We agreed to put ourselves in the running. Two weeks later, we got the call: whatever audition had just taken place, our house had nailed it.

It was all very flattering and exciting. On the other hand, I knew that turning our home into a movie set was a gamble, and not just because of the risk of property damage. Back to the Future fans have been racing skateboards outside Marty McFly’s house for nearly forty years now. The owners of the Breaking Bad house had to install a six-foot fence to keep idiots from tossing pizzas on their roof. I knew we could be dooming ourselves to a lifetime of gawkers peering into our windows or sneaking into the yard. Once it was on-screen, it would no longer be our house. It would be “the house from Love & Death.”

There were obvious benefits too. HBO Max offered us a generous fee—twice what I make in a full year of writing, if I’m being honest—for one week of filming in the fall and another in the spring. They would put our whole family up in an Airbnb and pay for our poor cats to be boarded. We also would receive a separate compensation for every month we went without our fence and play set. Because I was a journalist—and, legally, couldn’t be kicked off my own property—I would be allowed to hang around and observe, so long as I passed a COVID test and generally stayed out of sight. Even more than the money, I must admit, the thrill of celebrities milling about our house proved irresistible. We signed the contract.

Of course, the allure of playing host to film stars fizzled out somewhere around the forty-fifth minute I spent watching Patrick Fugit pretend to mow my lawn. Because our house was used largely for exteriors, a lot of it was mundane business—mostly transitional scenes involving cars. On the first day of filming, Jesse Plemons and Lily Rabe pulled a pickup truck in and out of my driveway for about an hour, while Fugit and the child actors pitched horseshoes in the grass. Another afternoon was lost watching Krysten Ritter drive up in a Chevy hatchback, passing a group of extras posing as TV reporters who pretended to smoke from across the road. Sorry for the spoilers.

Friends, random passersby, and my editor wanted to know what the stars were really like, but truthfully, I had no idea. I kept my word and remained invisible, even during the rare scenes they filmed inside. I spied on Olsen from my basement office while she carried a laundry basket up and down our stairs, tensing up every time she passed over the narrow winder treads: one nasty tumble and I’d be blamed for ruining the Marvel Cinematic Universe. I stayed squirreled away down there while Ritter rang my doorbell over and over again for a scene that involved her picking up a card table— suppressing my urge to pop out and offer unsolicited notes on her Texas accent, which seemed to get twangier with every take.

I dared speak to the actors only once, bounding upstairs oh-so-casually to offer Olsen the Wi-Fi password, after I overheard her saying she couldn’t load something on her phone. The entire cast was there on a lunch break—all these familiar faces right inside my living room. I babbled an introduction from behind my mask. Olsen complimented me on the house. Plemons silently scraped the avocado from his sandwich. Unfortunately, I don’t think I’ll be mining a juicy tell-all from this, unless it’s about the time that Olsen, who used our bedroom as her dressing area, left its sliding door open all night to the elements and the possums. If Ryan Murphy wants to adapt that, let me know.

It was intermittently thrilling but, yes, often dull. I also knew that I was lucky to be bored. Most everything filmed here was of the happier times in the Montgomerys’ lives: a backyard barbecue, a baby shower, a trick-or-treating scene with dozens of adorable child extras in period-accurate Star Wars costumes. Lost in that fantasy of normality, it was easy to forget about the grim true story that was being told. Making peace with this would also be part of the deal.

In December, during the winter lull between shoots, Marissa sends us a text inviting us out to Kyle, twenty miles south of Austin. She wants us to tour the soundstages, where a life-size replica of our house has been built for filming interior scenes. Keaton and I drive into the industrial hinterlands, pulling up to a row of generic warehouses to find Marissa waiting for us. She leads us through an unmarked door that spits us out, disoriented, into our own backyard.

We stagger in a daze around a replica of the tree that grows outside our bedroom window. Marissa leads us to the front of our doppelganger home, past a sign reading “HOT SET” and into a precise copy of our entryway. Walking onto the landing, my hand swings instinctively behind me to close the front door so our cats won’t get out. Were it not for the workmen lugging sawhorses outside, this illusion would be entirely convincing.

We wander a hallway that is just like ours but leads to rooms stretched impossibly big and strung with klieg lights where their ceilings should be. There is the same stone fireplace in the living room, flanked by the same wooden lattice wall. Yet this room is large enough to fit a grand piano, and it spills into a kitchen five times the size of our own. Keaton remarks that it’s like that dream in which you’re walking through your house and you discover a room that you never knew existed. But of course this isn’t our house. It’s Candy’s.

Marissa takes us to the opposite side of the warehouse so we can visit our basement and downstairs patio. Just steps away from these, separated by cables and costume racks, lies the front door of the Gores’ house. We wander inside that too. We look at the wedding photos featuring Plemons and Rabe, and we check out the spines of the books in the library. Marissa takes us into the utility room, where Betty will meet her bloody end. We stand inside the nursery, where the neighbors will find Betty’s baby, hoarse from crying. For a moment we fall silent.

Whenever anyone asks me what this whole experience was like, I tend to lapse into cliché: It was crazy. A little traumatic. Surreal. But if I’m feeling expansive (or I’ve had a few), I’ll tell them that the most accurate description would be “hyperreal.” The philosopher Jean Baudrillard used that term to describe how modern reality has become indistinguishable from a simulation. We’re living in an idea of reality, Baudrillard argued, reconstituted from signs and signifiers that we’ve absorbed largely through our media. Maybe you, like me, remember learning about these ideas from The Matrix.

Filming locations are a good example of hyperreality. They’re places that are simultaneously real and imaginary, combining things that exist (like a house) and events that actually happened (such as actors filming a movie) with a fictionalized narrative. The story gives the location new meaning. The fantasy replaces the truth.

Baudrillard’s theory can be applied to true-crime shows too. Series like Love & Death purport to tell you a “true story”—such as the one about the killing of a woman in a small Texas town that destroyed the lives of several real people—but filtered through the lens of TV dramatization, with scripted dialogue delivered by talented actors. To the audience, that reconstruction can be so compelling, so intimate, so authentic that eventually the “true story” replaces the truth. So what’s it like to be immersed in that story, to live inside a house that, for many, will forever be Candy Montgomery’s? What’s it like to coexist with her presence and the pain she caused? It’s hyperreal, man. I don’t know how else to explain it.

The other thing that people ask me is whether it was all worth it. They mean the money—and in that case, sure. As my wife predicted, we also got a pretty good story out of the deal. Decades from now I’ll be boring some nurse with it. Already it’s brought us closer to our neighbors, giving us all something to chatter about at block parties. Some of the people farther up our street—the ones who endured the road closures, nighttime shoots, and noisy generators but weren’t paid nearly so well—would surely tell you that it was more trouble than it was worth, and they’d also be right. Yet I think they’d have to admit that even this makes for an entertaining anecdote.

In the end, though, there is a cost to surrendering your house to Hollywood that can’t ever be properly compensated or even accurately tallied. As promised, HBO Max returned all of our furniture intact. The crew took great pains to restore our house, down to the exact positioning of every painting. Our fence didn’t survive, and the replacement doesn’t exactly match. That Oldsmobile did, in fact, piddle rust-colored crud all over my carport. And once everything had finally been packed away, I discovered a sprawling semicircle of dead grass, a phantom imprint of director’s chairs stabbed into my lawn that has yet to fade, even after we had the whole area resodded. I guess there was a murder at my house after all.

But these are all superficial sacrifices (and certainly the money helps). On a much deeper level, this whole experience took something ineffable, forever altering our house and our sense of home in ways that we’re only beginning to wrap our heads around. It gave us a story, true, but it’s also made us part of another—one that’s not about movie stars but is filled with real-life pain, heartbreak, and misery. How exactly will that story unfold? All we can do now is watch.

This article originally appeared in the May 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Love & Death at My House.” Subscribe today.