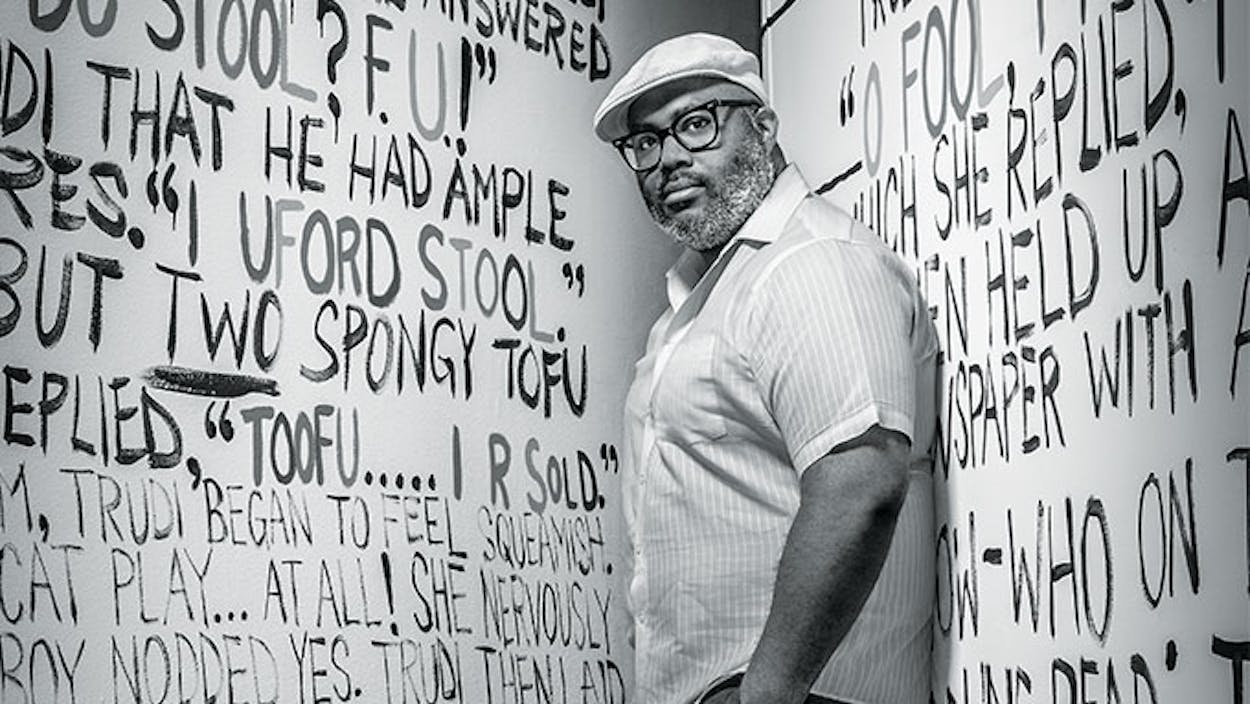

For twenty years Trenton Doyle Hancock has gained international renown for his paintings, which fuse cartoon-style drawing and abstract expressionism, creating a fantastical world populated by strange creatures known as the Mounds, their nemeses the Vegans, and Hancock’s alter ego, Torpedo Boy, who reflects his lifelong love of comic books and plastic action figures. More recently, the forty-year-old artist has turned away from this extended narrative to focus on more-autobiographical concerns. A retrospective, “Trenton Doyle Hancock: Skin and Bones, 20 Years of Drawing,” is on display at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston through August 3.

Jeff Salamon: You grew up in Paris. What’s distinctive about your hometown?

Trenton Doyle Hancock: It’s a small town with a lot of attitude—like, “Oh yeah, we’re big stuff in northeast Texas.” It has a superiority complex.

JS: Because of the name?

TDH: Years ago it was this major stop on the train, and that confidence has somehow remained in people’s DNA. Paris burned at one point—actually, it burned a couple of times—and that disrupted the industry there. If it had continued developing at the rate it was, it might have become Dallas; it could have grown to be alarger city. But there were these stumbling blocks—and I think that’s also part of the city’s psyche. Of course, as a kid I didn’t care about any of that. I fished for crayfish and rode my bike and drew pictures. It was a real easy existence.

JS: How did the town’s confidence manifest itself?

TDH: In the way people walked down the street, or the way we positioned ourselves against the other small towns nearby.

JS: I’m guessing football was part of that?

TDH: Football was the major way people identified with their town. And, of course, when I got old enough, I was right there on the team. I wasn’t very good, but I felt I had to represent my town.

JS: What position did you play?

TDH: The bench. [Laughs.] I was an offensive tackle.

JS: In many ways you had a very traditional Texas upbringing—the church was central to your childhood, your extended family was tightly knit, and you played football. But your stepfather, who was a minister and a factory worker, also ran a karate school in your house. Did that spin you in a slightly different direction?

TDH: My stepdad wasn’t the typical example of a black man that people had in their minds as an archetype. He wasn’t interested in sports. He saw karate as a method of self-discipline. And he had an amazing work ethic; he probably worked harder than any person I’ve ever met, which is probably why he passed away earlier than he was supposed to. The man never slept. In some ways he laid out the best blueprint for me for how to live a life. But it was also a cautionary tale.

JS: How did he get into martial arts, which I would think would have been somewhat unusual in rural Texas at that time?

TDH: It was in the late sixties, early seventies when he started to become interested in Eastern philosophy—of course everyone was, it was the time of Bruce Lee and Chuck Norris, it was all the rage. It was a certain idea of masculinity that he became interested in and wanted to promote, and now that I’m in the art world, I look back on it and think, “Wow, that was performative.” There was a lot of poetry in his gestures, in the way he moved through space. These people would gather at our house and have these very formal rituals. It was different than the rest of the stuff that was going on in Paris, Texas. Sometimes I look back and think, “Wow, I had a much richer experience than sometimes I like to think”—and a stranger experience than I guess I ever noticed.

It’s funny—some of the Eastern stuff can sometimes be seen as antithetical to or in opposition to some of the biblical things. He created his own sense of how to marry those ideas together. Even though he probably wouldn’t have talked about it that way, in retrospect that was a great thing for me to grow up around.

JS: Because?

TDH: Because that’s what I do. I take bits of philosophies from all over to create my art. I think that’s a healthy thing to do.

JS: Was it confusing for you as a kid that there was Eastern philosophy stuff and this Christianity going on?

TDH: Not at all. No one told me that it was confusing, so I just saw it as, this is the way things are—that I’d go watch Bruce Lee at the drive-in theater and then come home and my dad is doing the same stuff. The idea of superheroes was very real to me. It was, like, “Oh, look, you can do whatever you want to do in this life because, yeah, my dad breaks bricks and boards and uses swords and throws knives just like that guy on the big screen.” There was no separation between fantasy and reality, really.

JS: He was the man who raised you.

TDH: From before I can remember, maybe age two.

JS: You were born in Oklahoma, but you moved to Paris when you were . . .

TDH: Just a few days old.

JS: Are your family’s roots in Texas or Oklahoma or both?

TDH: I have family in both. The family I grew up with are all either still in Paris or in the Dallas area. On my biological, birth father’s side, they’re all in Oklahoma City.

JS: You grew up in a part of Texas that’s closer to Oklahoma and Arkansas than to most of Texas. Do you think of yourself as a Texan?

TDH: Yeah. It’s funny—growing up in Texas, people stick their chest out in a different kind of way. In school we had Texas history, and when I tell that to people who grew up, say, in Virginia or Maine, it’s like, “We didn’t take Maine history—what is that?” So there was this sense that we’re from another planet or something. Then there’s this idea of tall tales—there were the stories that were passed down in my own family about the trials and tribulations that my folks went through, and there was the biblical mythology that I was getting. And all of that was associated with Texas, this idea that stories are much bigger and much grander and they maybe mean more, and that gets in your psyche. I just happened to take it to heart and become a storyteller myself.

There’s also this sense of space that’s very different here than in a lot of other states. I lived on the East Coast for a few years, and I treated it like I was a Texan—I still spread out, I needed a certain amount of space. There was this constant battle between me and that area of the country. So I think it was only natural that I gravitated back toward an area of the country where you’re entitled to more space, somehow.

JS: This was in Philadelphia?

TDH: Yeah.

JS: How did Philly hem you in exactly?

TDH: The highways weren’t big enough for me! [Laughs.] Driving was terrifying up there. I like to relax and know there’s two lanes on either side of me. And it wasn’t like that up there. It’s basically just two lanes, and people will be like, “I got to get around this guy somehow,” and they’ll just cut off your bumper and keep going. And I was like, “Oh, this is crazy.”

Also, the houses are much closer together, the streets inside the city are much more confined, and just how people use personal space is different. You get used to it. Especially when I’m in New York, as soon as you step off the airplane or the train or whatever you understand that your space is calibrated differently immediately. It doesn’t bother me any more but it took some getting used to.

JS: You went to school at Texas A&M–Commerce and drew a comic strip for the campus newspaper. There are some examples of the strip in the exhibit at the CAMH, and they’re pretty naked emotionally—there’s a lot of anxiety on display. Was putting that out there in front of your classmates when you were a young man a tough thing to do?

TDH: All the women in my family are teachers, and there are a lot of ministers too. So I got this early training to go up in front of the church and talk, and be the one in class who raises his hand and speaks. Putting those cartoons out there didn’t bother me one bit. Any persecution that came, it was welcome.

JS: What kind of persecution came?

TDH:There was this column in the paper about some corrupt activity at a fraternity, and I followed it by drawing this critical cartoon involving a fraternity boy. And they hated it. One of the fraternities held a newspaper-burning party in front of their house. My editor was like, “Maybe you should lie low for a few days.”

I was like, “Wow.” I liked the idea that the things I drew could affect people in that kind of way. But generally the response to what I was making was pretty positive—people looked forward to what was coming next week because they had no idea—the cartoons had gotten increasingly more absurd and out there, just ’cause that was a need I had at the time.

JS: Was Gary Larson of the Far Side an influence?

TDH: I looked at a lot of Gary Larson. A guy named Dan Piraro, who did a strip called Bizarro. A strip called Red Meat. I thought that was going to be my life after school. I was grooming myself to be a cartoonist. I was going to continue to paint forever, but I didn’t think that was going to be a career.

JS: In 2000 you moved to Houston to take a fellowship, and you’ve been there ever since. What’s the appeal?

TDH: It’s close enough to my family that if I need to, I can jump in the car and go. But I know they aren’t going to just pop in and be at my door. [Laughs.] Houston also has the best thrift shops in the country.

JS: Why?

TDH: It’s a very casual city, not a hipster-heavy kind of a city. In New York the hip folks make their way into these thrift shops and buy up everything and then they start their own shops and resell. Austin’s the same way. But Houston is kind of untouched, which I appreciate. I get to go in and get my run of the whole lot of it, for quite cheap. Which is why my house and my studio are overrun with stuff.

JS: What do you look for in thrift shops?

TDH: Anything that’s strange. Toys, vintage children’s books, science books, records. Any and everything, because I got to a point where I also sell on eBay, so that’s a whole other life. I guess you could call it a hobby. It channels its way back to my artwork, so I guess it’s a little more than a hobby. Some of the objects are used as a kind of one-to-one inspiration for either the paintings or my own sculptures.

JS: Do you buy stuff with the intent of selling it on eBay, or at some point does it just lose its energy for you and it’s time to unload it?

TDH: A little of both. I try to develop my eye. I see it as an extension of this idea of being a superhero—you can see things that other people don’t see. I like the idea of going into a thrift shop and then scanning it like Superman scans a building, looking through walls and seeing that hot item, and then I grab it and pay 25 cents for something that I know I can get $100 for. That’s such a great feeling.

JS: Those numbers are not made up?

TDH: Those numbers are not made up. In fact, there was once—and I didn’t sell this object, because it was something I wanted—but I had tried to get this robot on eBay, and I kept getting outbid—it went consistently for $300 to $350; it’s from the sixties. I thought I’d never see one in my lifetime. And the next day I go to this thrift shop, and it’s sitting there—I see it from across the room, in perfect condition. It was the weirdest thing. So I ran—I’m knocking little children and old ladies over to get to this robot—and it was $3.50. And I grab it, it’s the holy grail. And to this day I can’t believe I found that robot.

JS: There’s a certain poetry there. It was $350 online and you got it for $3.50—exactly 1 percent of the price.

TDH: Yeah, there’s something to it.

JS: Do toys still mean as much to you as they did when you were younger?

TDH: They mean more. When I get within a hundred yards of a thrift shop or a Toys “R” Us, my body changes; there’s a physiological change in me. I think every artist has this other thing that fuels what they do. For me, it’s toys. If I have a set of He-Man action figures and I’m working on a painting, the challenge for me is to make the painting as visually interesting as that pile of toys. There’s a kind of integrity I see in that design that I try to transfer over into the things that I make.

JS: How did you get started on this whole thrift shop thing?

TDH: My collecting went full force when I got to Philadelphia, which, I must say, had the best flea markets in the country. I got really spoiled, because there, and pretty much in all of Pennsylvania, there was a healthy, just insane flea market culture. So on the weekends my girlfriend and I would get in the car and travel pretty much all over Pennsylvania and sometimes right there in Philly, and these parking lots would open up and people would just have blankets on the ground—they’d be covered in toys and old car parts and magazines. This was just before the Internet was superhuge, and I didn’t know much about eBay and there weren’t a lot of specialty websites at that point, so that was the only way to see large groups of things that people had curated. And the memories just started coming, coming, coming, and I was like, “Wow, I want to be part of this, I want to be a collector, I want to have these memories next to me, so that I can respond to them.”

That’s when the collecting bug truly started. My mission at that point was to get every toy I had as a kid that maybe had gotten thrown away. Then it turned into, I want to get every toy that I didn’t get as a kid but I wanted, so that was another thing. Then the Internet thing really happened and I was fully into it. I was able to see other collectors and hear their thoughts on this culture. And then it turned into, “Well, I want everything that is tangentially connected to the things that I wanted that I didn’t get.” Then it was like, “Well, I guess I’m just interested in the idea of toys. That’s when it became more than a hobby and turned into a mission, a life mission.”

JS: Are there any specific sorts of toys that you’re interested in?

TDH: The Star Wars format of action figures, Masters of the Universe—the eighties is home base for me. There’s a complexity to those figures that I find rewarding.

JS: Is the complexity actually in them, or is it in your head?

TDH: The complexity is in them, but it’s also in how they relate back to whatever the source material is. So when I see the Star Wars action figure, that prompts me to want to learn more about George Lucas’s writing and the films; it’s like an entire universe. It’s sort of like Catholicism—you have the Virgin Mary statuette in the sanctuary or the stained glass windows, and those things sort of draw you in. I see the little Han Solo and Greedo action figures as these conduits to get me into that universe. In the same way, I see my paintings as a conduit to get into something much larger. It’s like, yeah, I can focus on the materiality and design of this object itself, but beyond that I’d love for that to be a gateway into this much larger philosophy.

JS: What was more powerful for you as a kid, playing with superhero toys or reading superhero comics?

TDH: The funny thing is, I didn’t really play with the toys. I was a weird kid. Me and my brother, we were both the same—we would set up situations and step back and look at what we had set up. So we would get all of our action figures, set them up on the bed, create little mountains and things, have strings coming down and set it all up perfect, and then we’d go to the door of our bedroom and just look at it. He’s an artist too now— he’s more a graphic designer—and I feel like we both do that in our studios. But this idea of getting something out of you, setting it up, curating it or whatever, and then stepping back and reflecting on it to assess what you could tweak or change or how could you make it better—that’s what artists go through. And I think the toys were just practice to get there.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

- More About:

- Art