This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

John Howard cursed the holdup on the San Felipe highway and began pumping his legs in a furious rhythm that pedaled him nowhere. Howard could endure all the grueling physical challenges it took to win the world Iron Man title. He could ride a bicycle from Los Angeles to New York in less than ten and a half days, including food and rest stops. But he just couldn’t stand to wait.

He had come to this asphalt straightaway 84 kilometers south of Mexicali to prove that he could travel faster under his own power than any human being in history. His chosen vehicle was a bicycle. His goal: to break the world’s bicycle land speed record of 138 miles per hour. Howard was hoping to go at least 140, and preferably 150, so he could shatter the old mark by an indisputable margin. But before he could go anywhere, the seven-mile strip of desert highway he was using as a make-do speed course had to be cleared.

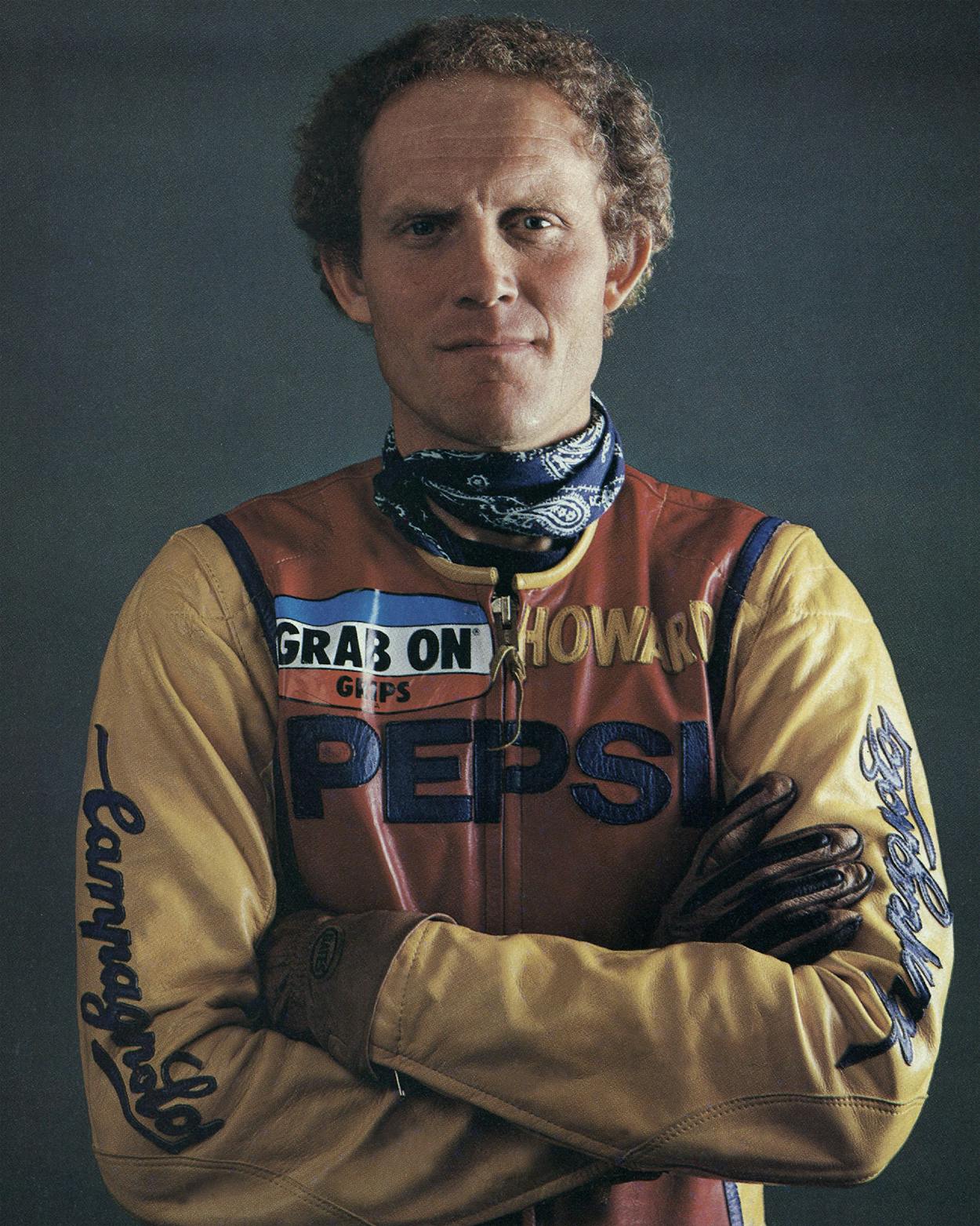

As Howard kept on swearing to himself and pedaling in place on his bicycle stand, he resembled an advertisement for some spaceage stationary exercise machine. His face and physique were obscured by head-to-toe protective coverings: a full, visored yellow crash helmet, red and yellow motorcycle racer’s leathers, turquoise boot covers, and black knob-soled bicycle racer’s shoes. His leathers sported the name “Campagnolo” down each arm and a big blue block-lettered “PEPSI” across the chest.

The remarkable apparatus Howard was straddling also appeared to be suffering from an identity crisis of design. The brightly painted yellow frame resembled that of an ordinary racing bicycle, but there were two drive chains instead of one. The most curious appendage of all was a rubber-capped vertical bumper bar that jutted out in front of the handlebars like a miniature yellow flagpole. The rest of the contraption looked like a hodgepodge of motorcycle parts. Instead of resembling the large, slender circumferences of a racing bicycle, the wire-spoked chrome wheels of Howard’s bike seemed small enough and wide enough to fit a Honda 50 motor scooter. The handlebars did not curl under, ten-speed style, but extended straight out and featured short black handgrips similar to the throttle of a motorcycle. A gray wire led from the right handgrip to a radio transmitter built onto the frame. Another gray wire led from a second radio box, taped onto the seat tube, to a tape-covered coil around Howard’s waist, then continued up his racing leathers to his crash helmet. A line of red letters on the frame read, “Pepsi Challenger.” The bike had been custom conceived and constructed in Texas. There was nothing else like it in the world.

Whenever Howard looked up from the Pepsi Challenger to check for progress on the highway, his line of sight was framed by the sides of a rectangular Plexiglas window several feet in front of his bicycle. The window served as the viewfinder through the mouth of a five-by-four-and-a-half-foot wind fairing orthodontured with cameras. The fairing in turn flared out from the tail of a rocket-shaped white race car with a horizontal chrome bumper bar across the rear. From Howard’s position directly behind the race car, the fairing looked like a giant TV console, and in the images coming through the viewfinder everything on the highway looked low and narrow.

What Howard saw wasn’t entirely an optical illusion. The race car parked in front of him was itself quite low and narrow. The top of the fairing measured 5 feet above the pavement, but that was by far the car’s highest point. The tail section sloped into a 21-foot-long aerodynamically dimpled fuselage that was only 2 inches above the asphalt and 41 inches in diameter. Those dimensions provided just barely enough breadth to hold the semi-reclining driver. Including wheels, engine, driver, and all, the car still weighed less than 1500 pounds.

Of course, as Howard knew, the size of the car in the race did not represent the true size of the race in the car. The compact little fuselage in front of him carried a modified 350-cubic-inch Chevrolet engine that could produce 540 horsepower and speeds in excess of three hundred miles per hour. When hurtling down its home course at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, the car generally wore a thin, fin-shaped tail section and carried the appropriate title of “Streamliner.” But along with its special rear-end fairing, the car had been given a new name in honor of Howard’s world record attempt: like the bicycle behind it, the car bore the words “Pepsi Challenger” on both flanks.

“Hey, Julio,” Howard shouted suddenly in midpedal. “Can’t we send somebody up there to find out what’s going on?”

Although Howard’s voice naturally carried only a few inches beyond the visor of his crash helmet, his words reverberated like thunderpeals inside Rick’s helmet. A startled voice blasted back at Howard with equally resounding volume.

“What the heck are ya yellin’ about, John? You’re breakin’ my eardrums.”

Howard felt like an idiot. He had unintentionally detonated the concentration of the man on whom his life most depended: race car driver Rick Vesco.

“Sorry, Rick,” Howard apologized sheepishly. “I forgot my voice radio was on.” Howard reached for his right cheek and flipped a switch near the gray wire that trailed from his crash helmet. Then he sat up straight in the saddle and scanned the crowd on either side of the highway.

The fifty to sixty people on hand to watch Howard’s world record attempt hardly amounted to a cheering throng, but they did make a colorful and motley sight. Several flat-bellied young men and one young woman in red-and-yellow Pepsi Challenger Windbreakers and soft cotton Campagnolo bicycle racing caps scurried about with video cameras, rags, and wrenches. Several other trim, athletic-looking men clad in T-shirts and jogging shorts and some beer-gutted fellows in jeans and Windbreakers fussed over the race car and the truck it had come on. A two-man team of white-uniformed Mexican paramedics waited beside a white ambulance on one side of the highway, while about twenty Mexican locals and two or three American motorists just passing through milled around nearby.

Instead of watching Howard’s pedaling or the stretch of asphalt ahead, most of the spectators were looking skyward. Their attention was focused on the sensational maneuvers of a green and white Hughes helicopter. As the delay continued, the helicopter kept swooping, looping, dipping, and hovering back and forth across the highway.

Howard lifted the bottom of his crash helmet and called out again. This time his words reached the intended party. Julio Marquevich materialized beside Howard’s bicycle. Marquevich was a short, blotchy-faced Argentinian with a gray moustache. He happened to be the North American president for the Italian bicycle-parts maker that was one of Howard’s principal sponsors, but he looked as if he were dressed for a day at the country club. Instead of wearing one of the bicycle racing caps, he displayed the Campagnolo logo on a baby-blue golf cap complemented by a white Windbreaker, a sport shirt, and slacks. He also puffed on a filter cigarette in a white plastic holder.

“Don’t worry, John,” Marquevich assured him with a Latino-Germanic accent and air. “I will find out the problem right away.”

Howard kept pedaling in place and staring through the viewfinder of the wind fairing until he saw Campagnolo’s white station wagon disappear down the highway. Then he switched on his voice radio to tell Vesco what was happening.

Both cyclist and race car driver had made it a practice to share each bit of new information they received, no matter how trivial it seemed at first. The two of them would be zipping down the highway together at two miles a minute. They had to stay in perfect tandem at all times, for the success—and the safety—of Howard’s world record attempt depended on keeping the bicycle in the slipstream of the race car.

The “motor pacing” technique did not constitute cheating. The current world record holder and all his modern predecessors had also pedaled behind some kind of pace car. There was virtually no other way to break the 62-miles-per-hour barrier.

Like most previous world record setters, Howard would begin his run by being cable-towed up to sixty miles per hour. Although it was possible for him to reach that speed purely under his own power, the gear ratio of the Pepsi Challenger was so extreme that the effort would require at least four miles. Rather than waste all that energy and distance, Howard would let the race car do most of the work for him. But once he hit sixty, Howard would release the cable and start pedaling on his own. Car and cycle would have about two miles of runway to reach record speed. Then they would enter the “timed mile,” a surveyed 1760-yard section marked by electronic eyes at beginning and end. After they passed the second timing trap, they would have about three quarters of a mile to slow down and stop.

Riding the slipstream was no downhill coast. The slipstream was a protective envelope that extended only seven feet behind the race car. That meant Howard had to keep his bicycle’s front wheel within an invisible ten-inch pocket at all times. He would literally be chasing Vesco down the speed course. If he did not pedal fast enough to keep pace with the car, he would lose the protection of the fairing. The wind rush at that speed was so forceful that riding into it felt like smashing against a brick wall. Howard’s bicycle weighed 46 pounds, which was heavy for a bike, but it was far lighter than a high-speed motorcycle like the 550-pound Triumphs and Harley-Davidsons. If Howard veered outside the slipstream of the race car at that speed, he could be blown off the road like a twig. And if he gained speed too quickly, he would hit the bumper bar on the fairing.

But the greatest and the unavoidable danger was slowing down once the run was over. The single hand brake on the Pepsi Challenger would simply melt or lock if Howard tried to squeeze it at speeds over one hundred miles per hour. The only way to decelerate was to bang against the bumper bar. Each bone-jarring collision carried the risk of a nasty fall, and Howard would have to hit the bar several times in order to slow down enough to apply the hand brake and venture outside the slipstream.

Howard began backing off his warm-up pace as the delay on the highway continued. He was growing more and more concerned about the shifting wind. A head wind, from the north, would be no problem. Thanks to the fairing, he would be fully protected. A head wind might even help stabilize the race car and keep them straight on course. A tail wind wouldn’t be strong enough to affect them one way or the other. But the worst of all possibilities was a crosswind. Any unexpected gust from east or west could buffet the bicycle at least slightly off course. If the crosswind grew strong enough, it could even push Howard out of the slipstream altogether.

Just as Howard noticed the wind starting to cross his path diagonally from the south-southwest, Marquevich returned with a disconcerting report on the holdup. A lopsided old hay truck had stalled in the northbound lane just past the timed mile. Its tires were flat, its brakes were locked, and it was out of gas. Someone had tried to tow it off with a four-wheel-drive vehicle, but the truck, loaded with about 36,000 pounds of hay, simply would not move. Now the federales were trying to pump air into its brake lines before attempting another tow.

The obstruction created by the stalled hay truck would make an already dangerous speed course even riskier. The stretch of roughly poured asphalt in front of Howard and Vesco was only 27 feet wide, and it was elevated about 11 feet above the flats by steep, rocky grades. Although the road surface looked level at first glance, it harbored several deceptive and treacherous swells that Vesco called whoop-de-dos. Those whoop-de-dos had caused Vesco’s car to become momentarily airborne on just about every test run over 110 miles per hour. If the car left the pavement even for a split second, it could come down at an off angle. Since the Streamliner was designed for straight speed runs, its steering was very limited. If Vesco did not manage to wrestle the wheels back on line, he could plunge headlong down one of the rocky grades.

Zooming past a heavily loaded hay truck would add to the problem. Even if the truck was moved to the shoulder, it would create a sizable “draft.” Racing past the truck would be a little like flying an airplane through choppy air—except that an airplane never loses contact with the air, and the truck’s draft would cause the race car to veer or, if it coincided with a whoop-de-do, to lose contact with the pavement.

The hay truck posed a still greater threat to John Howard. Passing close by a truck at 55 miles per hour was enough to give a cyclist a good shiver. The shuddering impact of hitting the hay truck’s draft at more than twice that speed might knock Howard out of the protection of the fairing. If the draft merely buffeted Howard a few inches sideways, that small misdirection, combined with a whoop-de-do adjustment by Vesco’s car, could also propel Howard into the wind wall. Either way, he would be plastered against the pavement.

Howard had no choice but to wait until the hay truck was moved. As if to remind him of the consequences of doing otherwise, the rusted hulk of a Chevrolet station wagon lay in a lingering rain pool at the base of the westward grade a few yards beyond the starting line. A short distance farther down, on the opposite shoulder of the highway, there was a low mound of dirt marked by a small white wooden cross. Howard looked up at the abandoned car and the solitary cross, then lowered his head again and kept on pedaling in place.

Howard would have preferred to stage his world record attempt on the faster, smoother, and much safer salt flats up in Utah. But unseasonal fall rains had flooded the Bonneville speed course with three feet of water, and everyone said it would take several more months for the water to drain off. Efforts to get permission to run on the space shuttle landing strip at Edwards Air Force Base in California had been snarled in government red tape, and no other site in the U.S. appeared to be long enough and straight enough for the attempt. Then a Mexican promoter and friend of one of Howard’s American cycling buddies offered to provide a highway in the Baja desert immediately.

Howard recognized the dangers of the uneven asphalt desert road, but he didn’t want to keep on postponing his assault on the history books. He couldn’t afford to. At the age of 35, John Howard was an impressive physical specimen. Although his 6-foot-2-inch, 165-pound frame was skimpy through the arms and shoulders, he had massively muscled thighs 22½ inches around and carried less than 4 per cent measurable body fat. He had a wide, square, and handsome jaw, curly blond hair, and crystalline blue eyes. But as the crow’s-feet around his eyes and the crazy quilt of scar tissue on his accident-battered knees hinted, John Howard had reached the peak of his athletic prowess.

Howard’s dream of setting a world bicycle record could be traced directly to his childhood. Like a lot of all-American middle-class kids, Howard got his first bicycle, a bright red Schwinn, back in the first grade. But the turning point of his life came in junior high school when he and his younger brother got two of the new European racing-style Schwinn Continental ten-speeds. The Howard brothers had the first curled handlebars and derailleurs ever seen in their hometown of Springfield, Missouri. Because they preferred riding their bicycles to driving cars or pickup trucks, they were considered weirdos by their classmates and neighbors. “That just wasn’t done back then,” Howard recalled. “Especially in a small town. You either drove a car or walked. You didn’t ride a bike. I was a nonconformist. I didn’t have too many friends.”

Although Howard had some success in football, track, and swimming while in high school, he saw cycling as an individual sport in which he had talent and the potential to excel. Anxious to prove himself to his father, who had wanted his son to be a football star, John entered his first bicycle race in the summer following his senior year. The race was a 102-mile endurance test across the cornfields of Kansas. Although he had never cycled that far in a single day, he managed to finish in second place. From that point on, Howard began taking the sport seriously. When he entered Southwest Missouri State in Springfield that fall, he also entered more races. Two years later, at the age of nineteen, Howard won the U.S. National Road Racing Championship, his first national title. He also made the 1968 U.S. Olympic cycling team.

Howard’s exploits in the decade that followed later prompted one cycling writer to label the seventies the John Howard Era of American Racing. Between 1969 and 1979, Howard won fourteen national titles and major road races and competed on two more U.S. Olympic teams. In 1971 he also became the first American cyclist to make a name for himself on the international scene by winning the first individual U.S. gold medal in the Pan American Games as well as first-place medals in the Tour de l’Estre in Montreal and the Tour of Newfoundland. But for all his success, Howard never became a celebrity. Although he moved from Missouri to Texas in the early seventies and won most of his cycling titles while based in Austin, he wasn’t even as well known as the third-string quarterbacks at the University of Texas.

In Texas he began gearing his workouts toward competition in one of the world’s most demanding physical endurance events: the annual Hawaii triathlon. The contest is best known as the Iron Man triathlon, or simply the Iron Man. It is a full triathlon, which means that it consists of a 2.4-mile rough ocean swim, a 112-mile bicycle race, and a 26.2-mile marathon run. Pounding breakers, treacherous currents, steep hills, dead lava flows, and bumpy pavement are all part of the course. Training is a year-round affair.

John Howard had no interest in merely completing the Iron Man—he wanted to win it his first time out. In February 1980 Howard covered the course in an impressive 10 hours and 35 minutes. But that was good for only third place. For the twelve months that followed, Howard pressed himself harder than ever before. His weekly training regimen swelled to 35,000 yards of swimming, 350 miles of cycling, and 70 miles of running. In February 1981 he won the Iron Man with a record time of 9 hours and 38 minutes.

By winning the Iron Man title, John Howard gained more acclaim than he had earned in a decade of championship bicycle racing. Accounts of his exploits appeared on network TV, as well as in Sports Illustrated, the New York Times, and sports publications all over the world.

But not even an Iron Man could live by his press clippings alone. Howard was a proven world-class athlete in search of a self-sustaining sport. He fretted over what to do next. He had held only one regular job in his adult life, and it had involved public relations for a manufacturer of sporting goods. Even his two-year stint in the Army had consisted mostly of competing in Europe for the Armed Forces cycling team. By the summer of 1981 Howard was living in Houston, working in the North American headquarters of Campagnolo, which had received valuable publicity from his Iron Man victory. The following summer he began doing occasional TV commentary for CBS Sports. But Howard could not see himself just sitting around drawing salary. That’s when he hit on the idea of breaking the bicycle world land speed record, then held by Allan Abbott, a California physician who had gone 138 miles per hour way back in 1973 on the Bonneville Salt Flats in the slipstream of a modified ’55 Chevy dragster.

Although no one had attempted to better Abbott’s speed in nearly a decade, Howard concluded that the time was ripe for world-record breaking. It looked like the perfect stunt for getting his name back in the news. That, in turn, could lead to the kind of fame—and promotional opportunities—of which post-athletic careers are most lucratively made. By making history on a bicycle, Howard could at least temporarily satisfy his long-burning desire for success. He could also come close to realizing a recurrent childhood dream. Sometimes, when the weather was just right and Howard was pedaling his bicycle in perfect rhythm, he could imagine his front wheel lifting off the pavement and carrying him toward the sky. John could not help but fantasize that cycling faster than any human being in history would be a lot like bike flying.

Howard succeeded in getting $25,000 from Campagnolo-USA after soothing the company’s fears for his safety. Then, on the advice of two Iron Man competitors, he contacted Rick Vesco and his Bonneville Streamliner.

Vesco is a member of one of America’s most prominent racing families. The Streamliner was the brainchild of Team Vesco’s seventy-year-old patriarch, Rick’s father, John, who had conceived the basic design of the car back in 1957. Although the Streamliner had carried a variety of engines and tail sections in the last quarter century, its design had remained essentially the same. Rick Vesco nearly set a world record in the Streamliner when he whizzed through Bonneville’s timed mile at an average speed of more than 300 miles per hour, only to flip the car before he could complete the mandatory second run. Pacing Howard’s bicycle to 140 or 150 miles per hour seemed, in comparison, like a Sunday afternoon drive with the family: it would require only about half throttle.

Then Howard went to bicycle makers Doug Malewicki of California and Skip Hujsak of Austin. Malewicki, who had designed and built daredevil Evel Knievel’s skycycle, and Hujsak, who was one of the top independent bicycle designers in the country, listened excitedly as Howard outlined the requirements of the high-speed bicycle he wanted them to build. Like ordinary production bikes, the machine Abbott had used to set the existing world record had consisted of a one-chain, two-gear system. In order to accommodate a front gear capable of 130 miles per hour, the chain had to be angled upward, which meant the good doctor had essentially been pedaling uphill. To achieve greater speed, Howard would need an even larger gear. The problem was how to enlarge the front sprocket wheel without increasing the uphill factor as well.

The solution Howard, Malewicki, and Hujsak came up with was a “double-reduction” gear system using two chains and four sprocket wheels. Instead of linking the oversized forward gear directly to the rear axle, they would chain it to a small sprocket attached to an elevated support tube behind the saddle. Sprocket number two would turn on the same miniature axle as the third, larger gear. A second chain would connect gear number three to a fourth sprocket on the axle of the bike’s rear wheel. The result would be a lower center of gravity, more stability, and a greater range of gear ratios. Howard would thus have the option of installing large sprockets, which would require hard pushing but relatively slow pedaling, or small sprockets, which would require faster pedaling but less pushing to achieve the same speed.

As the production of the double-reduction bicycle slowly proceeded, Howard’s funds dwindled. He later estimated that about $10,000 of the $25,000 Campagnolo sponsorship money went directly into bicycle construction costs. Much of the rest was consumed by the expenses of everyday living. Appropriately, Howard pedaled himself out of the financial crisis by winning the Pepsi Challenge 24-hour marathon race around Central Park in New York City on the last day of May 1982. His national endurance record of 475 miles impressed the Pepsi-Cola people enough that they contributed about $25,000 toward his speed record attempt.

The first high-speed tests of the newly christened Pepsi Challenger took place on the Bonneville Salt Flats in July 1982. Nothing John Howard had experienced as a bicycle racer and triathlete prepared him for the terrifying thrill of slipstreaming down the salt. Before Howard got up to 60 and released the tow cable, his bicycle would wobble and shake like a wind chime in a tornado. Sharp granules of salt dust would swirl up from the track, elude the protective shield of his visor, and bounce against his stinging face and eyes. Howard felt that he was on the verge of losing control during every run. But on the last test run of the last day, Howard managed an unofficial clocking of 114.9 miles per hour. “At that point and not before that point,” Howard said later, “I realized that we were on target and that the record was within reach.”

Then the rain came to Bonneville, and Howard was forced to look south to Mexico. The site was called Laguna Salado (“Salt Lake”), but Howard would be running on an asphalt highway, not a salt flat. Vesco and Howard went down for some preliminary runs on the third day of 1983. The surface proved to be considerably narrower and bumpier than they had been told, and there were three bridges punctuating the roadbed. But on the final test run, Howard got up to an estimated 115, the same speed he’d last achieved at Bonneville, and both cyclist and race car driver decided to return the following week and give it a go.

Howard finally set out from San Diego on Sunday morning, January 9, at the head of a four-car caravan. His entourage included a three-man film crew, three still photographers, two journalists, two Campagnolo company reps, an English-born triathlete-yoga guru, and a combination girlfriend-nurse.

Howard and his caravan reached the desert campsite south of Mexicali about midafternoon. The place was marked by the 84-kilometer sign on the highway, an abrupt change in the thickness of the asphalt surface, and a solitary cone-shaped sand dune a few hundred yards from the western edge of the road. For lack of an official name, the caravan called its campsite by the generic auto racing term “the Pits.”

By the time Howard turned off the highway into the desert, Rick Vesco and his family contingent had already set up a ragged semicircle of mobile homes, vans, and four-wheel-drive trucks. The new arrivals touched off a frenzy of photo taking, handshaking, and soda pop, decal, cap, jacket, and T-shirt distributing, and more photo taking. Obviously unnerved by all the commercialism and commotion, Vesco took off into the desert on a Yamaha 550 dirt bike.

The sun started to roll over the western mountains, and the temperature began to drop. By the time Vesco finished his motorcycle ride, it was almost dark, the film crew and the Campagnolo reps were leaving for their motel rooms in Mexicali, and there was a campfire blazing in the Pits. The unlikely collection of super jocks, auto-racing junkies, and sports-spectacle groupies who settled in for the night had only one thing in common: their quest for a world speed record.

The next morning Howard and Vesco made two slow-speed tests on the San Felipe highway. On both trips the bicycle wobbled and shook so much that Howard had to wrench the handlebars with all his might to keep it on line. Vesco also had his hands full. The whoop-de-dos repeatedly caused the Streamliner to get airborne.

The essential art of slipstreaming also proved to be a problem. Howard and Vesco had originally planned to coordinate the speeds of car and bicycle with a remote control throttle. Once Howard released the tow cable, he would take over control of the pace car by means of the radio transmitter wired to his right handgrip. The signals transmitted from Howard’s bike would regulate the acceleration of Vesco’s car. But on the first run of the day, Howard pinned Vesco against the seat by twisting the throttle too quickly. When Howard let off to compensate for his mistake, he slammed into the bumper bar. Howard accelerated much more smoothly on the second run, but he discovered that he had to “feather” the brake, which was also located on the right handgrip, to help steer. One-handing both throttle and brake at high speed was just too much.

They decided to deactivate the remote control throttle for the last two runs of the day. The new plan left cyclist and driver in complete control of their respective vehicles. Since Vesco could not see Howard from the cockpit of the Streamliner, their only means of communication was the helmet-to-helmet voice radio, an inefficient medium at high speeds, to say the least. Unlike airplane pilots, Howard and Vesco could not count on “flying” on their instruments. Vesco’s cockpit contained no speedometer, only a tachometer. Vesco had attached a speedometer to the inside of the fairing, but the ride was so bumpy that Howard could hardly read it. The two most visible references in Howard’s line of sight were the white strip of tape on the speedometer’s 140-mile-per-hour mark and an orange-lettered bumper plate that read, “Faster You Fool.”

It was all going to boil down to an unspoken, almost mystical form of communication the race car jockeys called dialing in. That was the term for being in sync—with a car, a race course, a codriver. Having sacrificed remote throttle control, instruments, and eye contact, Howard and Vesco would have to rely largely on instinct, their practiced feel for each other’s reflexes and reactions.

Howard and Vesco seemed to dial in with ease. Although the third and fourth runs were even rougher and scarier than the morning runs, they were also incrementally faster. There was no official time for any of the runs because the tandem of car and bicycle was causing the timing traps to malfunction. But they believed they could get a pretty good idea of their speed from Howard’s speedometer and by estimating from the revolutions per minute registered on the car’s tachometer. They gauged the first, second, and third runs at 80, 110, and 120 miles per hour. Vesco had intended to pace the fourth run at 125, but when he passed through the first timing trap, he unconsciously kept on accelerating. They estimated that by the time he came to his senses they were going roughly 135 miles per hour. “I’m really sorry, John,” Vesco apologized afterward. “I didn’t mean to go that fast.”

Howard was too overjoyed to assure Vesco that an apology wasn’t necessary. “One-thir-ty-five!” he exclaimed, enunciating each precious syllable. “That’s only three miles an hour from the record!”

The next day, primed for the assault, Howard found himself idling in place waiting for the stalled hay truck to be moved. He groused that at this rate it would take until next week to get started. The wind was blowing across the highway from the northwest at about five miles per hour. And it was picking up all the time. If the crosswind became much stronger, the run would have to be scratched.

Then, without much warning, the signal came that the highway was clear. Vesco fired up his engine with a roar. An aide pulled the tow cable out of the fairing and hooked it to Howard’s bicycle. The official ended a four-second countdown and dropped his hand.

Howard got off to a fairly good start. When car and cycle reached the first timing trap, he was pedaling so snugly in the pocket of the fairing that the spectators at the timing stand first saw only the race car. Howard and his bicycle did not become visible until the tandem passed directly in front of the timing stand. Howard was pumping his legs in fluid rhythm. Then he hit a whoop-de-do a few hundred yards into the timed mile. The front wheel of the bicycle twisted first to the left and then to the right, but somehow Howard yanked the bicycle back on course.

Less than a minute later the run was over. Both Howard and Vesco looked shaken. That had been the roughest ride yet. Car and cycle had been airborne at least twice. The impact of pounding back down onto the pavement had made both vehicles tremble. “The road surface is just killing us,” Howard complained. “The car was really pitching around.”

The only consolation Vesco could offer was that the run felt like it might have been close to the record. Though they hadn’t been able to catch a clear reading, Vesco guessed that they might have done better than 130 miles per hour. Then the timing official radioed the truth: 120.192.

Howard looked devastated. That was nearly 20 miles per hour slower than the world record and 30 short of his goal.

“That’s the first run where I’ve really felt out of control,” he admitted. “I was really having trouble tracking the car. I came real close to coming out of the pocket. My forearms are just killing me from fighting those bumps.”

As if the difficulties of the road surface needed any further emphasis, Vesco discovered that the bouncing runs of the last day and a half had worn out a rubber “limiter” bushing on the front right suspension of the Streamliner. This tiny piece of rubber, similar to the suspension bushing of an ordinary passenger car, was designed to limit the shock when the car came down from a bump. Now it was worn through, and the suspension was rubbing metal to metal. Vesco’s already limited steering would be even more restricted if he tried to make another run. The car had to stay straight or it would go out of control. “The only way we can run is if we’ve got a straight head wind or a tail wind,” Vesco informed Howard. “Otherwise, we just can’t go.”

While the rest of the crew made lunch in the Pits, Howard took off into the desert on a dirt bike. He wore the same crash helmet and leathers he had put on for his bicycle attempt, and he seemed to go almost as all out. He zoomed back and forth across a brush-dotted flat near the Pits.

Rick Vesco also felt the need to let off some steam and headed for the highway on his red Yamaha. He was gone for half an hour or so, but when he returned, he announced some good news. He had just been down at the timing stand, and the wind gauge showed they had a 22-mile-per-hour head wind.

About two hours later, Howard was wobbling away in the wake of the race car. He looked much smoother than he had in the first run of the day. The bike still shivered when it hit the whoop-dedos, but Howard seemed to right himself more quickly. He also seemed to be pedaling faster.

The view from the roadside did not correspond to Howard’s experience on the bike. Although he also sensed that he was going faster, he later described the run as rougher than ever before. He felt car and cycle get airborne at least three times. Every time the tandem hit the pavement, paint and debris chipped off the belly of the car and swirled up under his helmet just like the salt at Bonneville.

When Howard started banging into the bar to slow down after the last timing trap, the car hit another whoop-de-do, the bike’s hand brake locked, and the bike leaned sideways. Howard thought he was going down, but somehow Vesco managed to pull the car back in line, and Howard straightened out the bike. “That one scared me a little bit, Rick,” Howard said as he pedaled beside the cockpit of the race car after the run was over.

“I’m scared, too,” Vesco admitted. “We’re approaching the outer limits of control.”

By the time the ambulance and the Team Vesco truck pulled up, both driver and cyclist were ready to call it quits. “I just can’t go any faster than that,” Howard confessed. “It’s just not worth it.”

Then the timing official radioed the results: 124.189 miles per hour. The new numbers changed Howard’s mind. He had established a world record for an asphalt surface. He had recorded the fastest human-powered time in ten years, the third fastest ever. But he was still 15 miles an hour short of the world land speed record. He couldn’t help but consider giving it one more try. “Do you think That’s Incredible! will be interested if I don’t break the record?” Howard asked a public relations man.

The PR man said he didn’t know, but he offered to drive to Mexicali and call his That’s Incredible! contact to find out. The round trip would take at least an hour and a half. By then it would be near four o’clock, and the sun would be dropping fast over the western mountains. There might or might not be just enough light left for one more run.

Rick Vesco finally said that he didn’t want to make another run. He was simply having too much trouble controlling the car.

“Only at that point did I agree to quit,” Howard said afterward. “I really didn’t want to make another run either. But from an ego point of view I needed to hear it from Rick that one hundred twenty-four miles per hour was all we could do on that surface.”

Back at the Pits that evening, Howard quickly made clear that he had no intention of giving up his quest for the world record. “We will go back to Bonneville,” he promised the campfire. “We’re gonna set the record. All that’s holding us back is three feet of water.”

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Longreads