It’s 6:30 a.m. and somewhere in the balmy dark, the feral hogs are trotting back from the nearby hay fields to make their bed in the mesquite timbers. I’m tiptoeing after the acclaimed 38-year-old novelist Philipp Meyer, one step behind and slightly to the right of him, clear of the radius of his Remington 700. And Meyer is one step behind our guide, a hulking, bearded man named Tink Pinkard, “a real teddy bear of a guy,” Meyer called him. It’s 73 degrees and the humid mid-April air is teeming with spring, crowded with bird chirps and clamoring with cicadas—that is to say, it is not the frigid fall hunting season. However, the 2.6 million feral hogs that maraud across Texas are always fair game.

Meyer, whose debut novel, American Rust, won a record advance of $400,000 and landed him on the New Yorker’s twenty under forty list in 2010, says hunting is the most important thing in his life other than writing. This is his last chance to check out a friend’s secret spot outside Webberville, just 20 miles east of Austin, before heading back to New York to begin the promotion of his new novel, The Son, a 576-page multigenerational epic about a Texas oil-and-ranching dynasty that is one of the most highly anticipated novels of the year. Don Graham, one of the foremost scholars of Texas literature and a professor at the University of Texas, told me it was the most ambitious Texas novel in thirty years—since at least Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian or Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove.

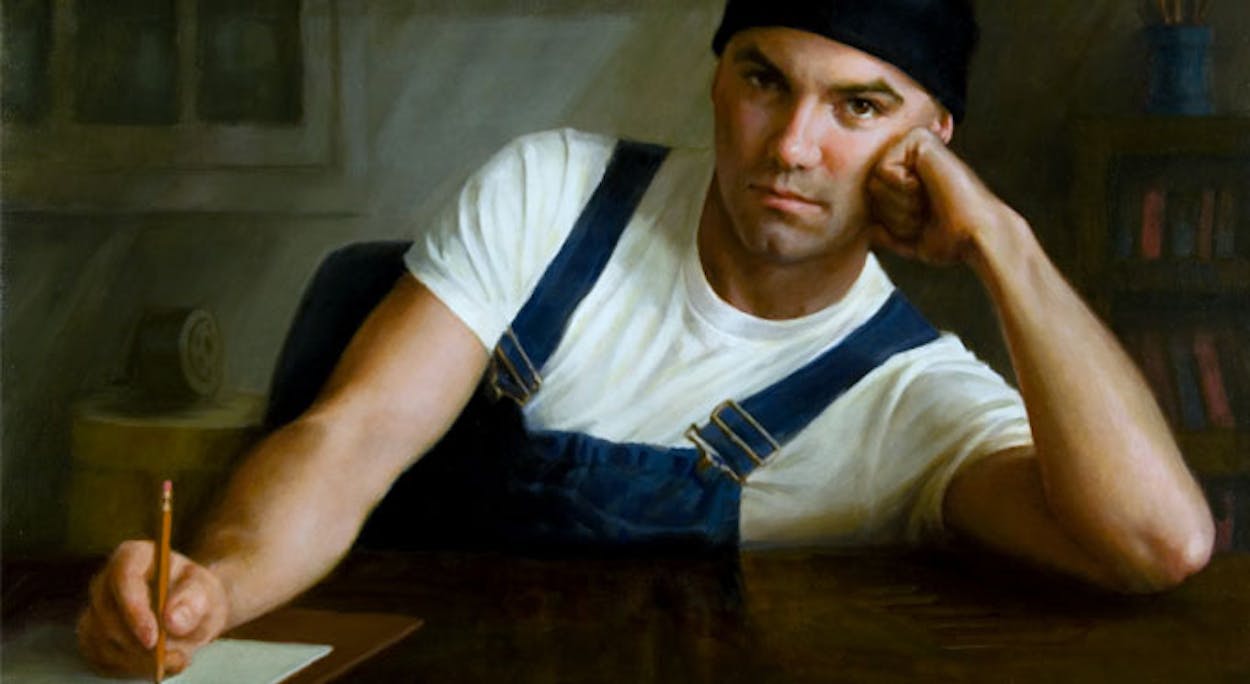

Standing in the grass, Meyer looks like a fit and comely Tony Soprano, if Tony Soprano shaved his head, wore hiking pants, and tracked down animals with a sense of serious purpose. “The chamber is empty, but the gun,” Meyer says, holding the firearm upright, “is not pointed at anything you’re not actually going to destroy, ever.” He is carrying three rounds in the gun and two in his pocket (he doesn’t anticipate that the three of us will be able to sneak up on that many pigs), and he speaks in a firm-yet-calm tone that I’ve noticed unites responsible gun owners—those blessed with the certainty of knowing that what they’re saying is actually of grave consequence. Meyer isn’t just mansplaining. Earlier I confessed to him that the only other time I shot a gun, I trembled. And given that I’m sporting the Adidas track pants I wore to eight grade PE class and a pair of nine-year-old New Balances that look brand new, it’s probably fairly obvious that I’m just as afraid of physical activity.

Meyer, by contrast, learned to shoot when he was five years old. His mother is a painter and his father, never having finished his biology PhD, taught as an adjunct. They lived in rougher areas, first the East Village of New York in the seventies, when it was cheaper and quite a bit fiercer; then Hamden, Baltimore, the butt of all his classmates’ jokes. His family always kept guns around the house for defense. “If you’ve grown up with guns, the thought that someone might take them away makes your stomach churn,” Meyer tells me. “They make you feel safe. If you didn’t grow up with guns, if you don’t know how to use them, then the thought that someone else has them makes your stomach churn.” He adds, “The only time I had a gun pointed at me was by a crazy liberal.”

Pinkard is wearing a thin camouflage jacket, which Meyer complimented earlier.It’s Sitka, a company that sponsors Pinkard and makes silent hunting gear in a camo that’s specifically supposed to foil an animal’s vision. Animals, Meyer tells me, walk around with their eyes all relaxed and blurry—perpetually in a state of soft focus—so that they can see more around them. (“The eyes are in front: predator. The eyes are on the side: prey.”) Fortunately camo isn’t all that important, especially when it comes to hogs, an animal that can’t really see that well. What matters most is how you move. Prey animals scan for action, and then narrow in on it and focus.

Not knowing what else to do while I trail Meyer and Pinkard, I’m trying to will my eyes into soft-focus, forcing my lids to droop and imagining my vision unzipping around my head 180 degrees. In this hazy state, I kid myself into believing I see the spooky white sclera of animal eyes. Turns out that’s not even what you look for. Most of nature is vertical, Meyer says, so I’m supposed to be scanning for horizontal blobs—backs just loping along. Of course, I might not see anything. This is hunting, after all.

Specifically what we’re doing, Pinkard says, is a “walk-n-stalk.” Most Texans, Meyer says, hunt at feeders or stands, merely waiting for an animal to come into view and then taking aim. “But that’s not hunting” Meyer says. Instead, we’re tracking the animal, alert to every sound and smell.

Meyer started hunting deer recreationally with some rural friends when he was nineteen or so, but it became a moral imperative in college. He ran over a squirrel and felt terrible about it, even though he ate ribs and hamburgers without a second thought. He went vegetarian for a while, but was always hungry, so he decided to “own” up to the killing, to “start seeing what’s horrible about it.” Now he hunts for a month or so a year.

We’ve got ten minutes until the 6:59 sunrise. As we amble toward the Colorado River, the men’s instincts tell them not to take a risk on the three lumps they see way off in the distance. It’s not certain they’ll get a clean shot. So we toe closer, hanging tight to the mesquite fringe. I stare and stare but without binoculars, or a scope, I see only the blackness. After we advance 100 meters, that’s all the men see, too. We’ve lost them.

As the minutes tick by, the sky desaturates, and the velvety black pigment fades into a luminous gray. When the wind swirls in our faces, the men bound forward. It is perfect, they explain excitedly: it will carry pig scent our way, and our own human scent backwards. No sooner does Pinkard say this, then he yells, “I smell ‘em!” And then after a few faint oinks, “I hear ‘em!”

Hunting and writing, Meyer later told me, are the two most important activities in his life. They’re both spiritual activities, he told me, and they’re both observational. “You trust your instincts and your animal nature. You never trust your intelligence, it’s always a year behind.”

Writing, however, is an intellectual pursuit, something, according to Meyer, that can feel like a real risk, one that he is proud of taking. “Emotional risk tolerance is what has lead to where I am now,” Meyer told me in his direct way, before the hunt. “I just assume that I’ll fail at something for several years—that I’ll try my hardest and still fail for several years. With writing that turned out to be wrong. I tried my hardest and failed for about fifteen years.”

At the age of sixteen, Philipp Meyer dropped out of a Baltimore public high school, but not before first asking a counselor how. (Answer: Just stop coming.) He worked as a bicycle mechanic for the next five years. “I was a retardedly good bike mechanic,” Meyer said. After all, his first comfort toy had been an auto repair manual. “Whenever I’m interested in something, I make sure I’m really good at it.”If you raced bikes in Baltimore, Meyer was one of the people you wanted to bring your bike to, he says. That’s how he ended up meeting, independently, two doctors that would become his mentors. “I ended up having a brief affair with one of the them. I was like twenty and she was thirty,” he laughed. “That was good.” Recognizing that he was a smart kid, they invited him to observe at the hospital. He liked it there. “The hospital appealed to the adrenaline-needing side of me,” Meyer said.

He got his GED and enrolled at a local college. He aced his courses, and the doctors encouraged him to apply to more prestigious schools, like Johns Hopkins. Meyer took their advice one step further, applying to a group of Ivy League colleges. He was rejected by all of them two years in a row. But his parents, he said, were supportive. “When you take the fact that you’re loved for granted, it frees your mind to go after every other thing there is.” The third year, Cornell accepted him.

Cornell marked a radical turning point for Meyer, and thus, perhaps, began his appetite for elite institutions. Or the sense of brotherhood spawned by them. As Jim Magnuson, the director of the Michener Center MFA program, said of Meyer, “I think he yearns for community. “All of the sudden I wasn’t alone,” Meyer told me. “All of the sudden I had tons of friends who were doing interesting shit, who continue to do interesting shit.” Then he added, “But there were fewer smart people than I thought. It’s more like one out of ten.” He entered Cornell as a premed but graduated, age 25, an English major with a 600-page “complete turd” of a first novel, wanting one of the few careers more exclusive than being a doctor: to be a successful novelist.

Trouble was that he had student debt. A Baltimore buddy temping at an investment bank told him that the 26-year-old traders were making half a million dollars a year. “I was like what is that job?” Meyer told me. “I f—ing want it. I don’t care what it is. That is the job I’m going to get.” And he did. He worked as a derivatives trader at UBS, writing his second novel on the side. It was, he said, soul-crushing. When he was halfway through his second novel, he quit. “How hard can writing really be?” he said he thought to himself. “Jonathan Safran Foer and Zadie Smith are making it.” But within two years (some of that time spent in Cambridge, Massachusetts), he had finished the second novel, and it had been “rejected by every literary agent that was worth anything.” Out of money, Meyer, then thirty, moved back in with his parents in Baltimore and applied to MFA programs. With two novels under his belt, he again applied to all the top schools. And again he they all rejected him.

That’s when he hit bottom. Until then, he says, he had been writing to hear himself speak. But now self-doubt forced him to consider the existential questions: What is Art and Why Am I Making It. And by the time he’d answered them for himself, he had been accepted to one of the most prestigious and best-funded MFA programs in America, the Michener Center in Austin, Texas.

“Nobody ever made better use of the three years of funding than he did,” the Michener Center’s senior program coordinator, Marla Akin, told me. “Fully-funded MFA programs are God’s gift to writers, basically the new patronage system,” Meyer told the Rumpus. And yet he also noted that for a writer to succeed in one, he must ignore all feedback. Meyer only read ten percent of the comments on his work-shopped material. He stacked them up, and at the end of the semester, he threw them all away. (“I didn’t expect anyone to understand not finished work,” he explained.) Magnuson, joked that when he had Meyer in class, he wore an “Armed Liberal” shirt and was always saying, “ ‘It’s not really written yet.’ He’d done a quick draft.” Magnuson told me that Meyer “was trying to get a sense of the structure, and then he wanted to edit it more.”

Random House imprint Speigel & Grau bought American Rust, Meyer’s novel about a small Pennsylvania steel town in decline, at the end of 2007, midway through his third year in the program. To celebrate, he bought every employee of the Michener Center a bottle of champagne. He still keeps in touch with the program, especially when he’s in Austin, where he lives part-time, sharing a house on the east side with two writers affiliated with Michener. And he is a warm and generous mentor, even when unsolicited. (“It’s our duty to help one another. Because what I did wasn’t efficient,” Meyer says.) Current students ask one another if they’ve gotten The Talk yet—Meyer’s advice to leave the people who have helped you come up in your profession because they’ll always view you as a greenhorn. “I think he has an old fashioned school spirit. He roots for the Center,” Magnuson said, and indeed Meyer introduced fellow Michener alum Kevin Powers, author of the Iraq war novel, The Yellow Birds, a 2012 National Book Award finalist, to his agent.

After graduating in 2008, Meyer loved Ithaca so much that he bought a house there. “It had always been my retarded dream to live in Ithaca,” he said. He associated it with the first time he felt intellectually fulfilled. And, Meyer said, “’cause that’s what you’re supposed to do in America. Have some success? Buy some property, . . . [it] was actually quite stupid.” The people who stayed in Ithaca, Meyer told me, weren’t ambitious, and they didn’t have much to talk about. Magnuson joked that Meyer said his agent had told him it’d be good for his career to live in New York. “Now, Philipp,” Magnuson told me he told Meyer, “I don’t think Ithaca is the New York your agent meant.” But Meyer was drawn to the idea of the enlightened rural lifestyle. “It was kind of a back to the land type thing,” Meyer said wistfully, “and I love that shit, man.”

As Graham, the professor whose class “Life and Literature of the Southwest,” would first pique Meyer’s interest in writing a novel about Texas, told me, “He’s really more of an old-style Texan than many Texans.”

If we were hunting deer, we’d have to head into the shade of the thicket, now that it’s light all over. Fortunately, we’re hunting feral hogs. The musky pig smell is unquestionable and the oinks are surfing the gusts of wind and skating past our ears. Meyer scampers up about fifty yards into the low brush then gets on his knees. With the briskness of a soldier, he points the gun toward the sound of the pigs to see through the scope. The pigs are traveling right across the horizon on slightly lower ground, behind a wild hedge of mesquite, such that from where I’m kneeling in the wide-open grass 150 yards away, the tops of hides are flickering through the branches like Morse code. Meyer fires, and the bullet smacks. It sounds like it might be a hit, but we can’t see.

The pigs bend round the mesquite hedge and start sprinting right toward Meyer and then, realizing with the sound of his second shot that he’s the enemy, veer to the right. Meyer shoots two more times as they pass. There’s one smaller gray hog, a few steps behind the rest, about sixty or seventy yards from Philipp. “Get that guy,” Pinkard says. Meyer tracks him with the scope and then shoots his last round. The gray hog goes down, but it is still breathing when the men run up to it.

Out of ammo, Pinkard slices his knife across its lower belly and slits its neck. Meyer puts his foot on the pig’s chest, and the pig kicks up its leg. And then the pig actually springs back up onto his feet, wearing two gaping and unnatural orifices, and takes two mad hops forward before Pinkard snatches the hair on his back with a firm fist and holds him down. The pig is bleeting and thrashing his head until the force of his thrashing flips him onto his back, and Meyer stabs his own knife deep into the pig’s throat. The blood burbles out in several waves like a toilet after it’s been flushed.

“I thought he was going to bite off my foot,” Meyer says. “He would have. All I thought was Kill, Kill, Kill.” The one thing I know about pigs is what I learned in organic farming: they’re the only farm animal that would happily eat a human alive. Feral hogs, with leaner muscle and tusks, are far fiercer.

With the small hog finally stilled, we walk toward the mesquite hedge to see what happened to the first shot that made a smack. Just beyond it lies a large brown boar—all 170 or so pounds of him are stiff. His breast plates, which evolved to withstand attack, feel firm as shin guards. The third hit, though, is not to be found. We follow the bright red beads on the green grass, some of which are swarmed with ants knocking antennae to feed on the blood. Having gone to bed only four hours earlier, kept up by The Son’s final pages, I feel like I’m reenacting the Comanche hunting scenes from the book.

The Son is a remarkable feat: a suspenseful and violent historical novel that is most notably literary. In the book, which comes out May 28th, Meyer clips between three characters of distinct generations and views, much the same way a Crossfit class clips between burpees and pistol squats—quickly alternating registers and working different muscles. There’s the impish and intuitive mythmaker and hero, Eli, the first son of the newly-minted Republic of Texas in 1836. Kidnapped as a teenager and raised by Comanches (some of whom, true to history, have obscene names, and in Meyer’s narrative often talk as if they’re in a locker room), Eli later becomes a Texas Ranger. Eli’s son Peter maintains Eli’s cattle ranch in South Texas. The first character Meyer wrote, the one who inspired Meyer to write a novel about Texas, Peter is the conscience and the critic during the Mexican massacres of 1915-1918. Lastly there’s Eli’s great granddaughter, Jeanne, an ambitious Republican oil baroness with a gay son and a drug-addicted daughter, two potential heirs with no interest in assuming the family company.

The writing is propulsive; so much so that the heft of the book almost creeps up on you, the weight of fully realized characters living their lives within the novel’s impeccably realistic architecture. Part of what explains the realism might be Meyer’s interest in “manly” activities and strength. “He has four or five pages in which he talks about cutting up a buffalo and what the Indians did. That’s Philipp,” Graham told me. I see it too. When we were first emailing, Meyer wrote with perceptible relish that he drank buffalo blood to research the book. (It tasted awful and musky, he informed me.) “I think in his dream life,” Graham said, “he thinks he could survive the Comanches.”

The research dovetails nicely with Meyer’s commitment to self-sufficiency. (He once got in a debate with a vegetarian writer friend about the importance of hunting, Meyer maintaining it is one of the most important skills in case of, say, nuclear attack.) And it was clear that our hunt had exhilarated him, liberated him in an existential way. “Welcome to freedom,” he said with a grin afterward.

Freedom is a predominant theme in The Son—the exhilarating expanse of choice and all the promise, expectation, and vulnerability that attends it. In this expanse, Meyer marries a libertarian optimism with a resigned, almost hapless nihilism. Optimism because every single flirtation in the book is consummated (it’s deeply satisfying and crowd-pleasing in that way). Nihilism because every consummation is also a betrayal of the tribe or the previous generation. Every affair is cross-pollination with the “other”—the ethnic other (a Scotts Texan with a Comanche); the socioeconomic other (a rich oil daughter with a poor oil scout); and the sexual other (a rich son of an oil family with another man).

This annihilation of what came before is also the story of America, the one Meyer wishes to tell. “We believe we went into this wilderness and the fact is there was no wilderness. The whole place was completely claimed,” Meyer said. “I hope that folks that are coming from the right wing point of view are like, ‘Oh, we did steal every inch of this land. Every inch.’ And that folks that are coming from the left point of view, who are inclined to see Native Americans as these holy, saintly human beings, will say, ‘Oh, people are just humans no matter what they come from.’”

Meyer, who talks about art much like the literary left of the forties and fifties as if it were an indisputable virtue, like liberty or justice, makes no bones about his aspiration to write the truest Texas novel yet. In The Son, a gaunt, self-important Edna Ferber visits Jeanne at the McCullough ranch to dig for dirt to fill her book, Giant, the last Texas epic. “Oh f— Giant, which was kind of a turd,” Meyer says when I mention this scene to him. “You know who else was writing then? F—ing Virginia Woolf. Faulkner.” Then he tells me that scene is based on truth: it happed to a rich Texas family that he’s friends with. The Son takes shots at Cormac McCarthy, too. “He was wrong about a bunch of shit. I mean I f—ing worship that guy, but writing this book made me respect him a little less,” Meyer tells me. “You have to smack down your forbearers, you know what I mean? You have to be like, ‘No, I’m the authority.’ ”

Meyer taught himself how to hunt. He taught himself how to write. He taught himself about Texas. And he is proud of this in the way that people who have taught themselves things typically are. “I was thinking I’d read 250 books, but that’s wrong,” he tells me. “I’ve actually read almost 350. Two-hundred-and-fifty is the number of books on my shelf that I bought.” Meyer first became interested in the subject in Graham’s class, though even when Graham and he started to meet for beers at Austin’s Crown and Anchor, Graham didn’t know it. He only became aware when he received an email out of the blue from Meyer, while Meyer was out West researching, asking whether he should set his oil family in West Texas or South Texas. West Texas, Graham advised, because then Meyer wouldn’t have to deal with race and the Mexican massacres. “He went ahead and did the opposite,” Graham told me. And “he did an amazing job of getting it right.”

Meyer told me his research was a matter of leapfrogging. He’d write until he got to the limit of his knowledge and then he’d research. “The Harvard library has a f—-ton of Texas books. They’re shittily written, but they’re first person accounts. They’re invaluable.” He added, “Bartlett’s dictionary of slang from 1855 is a goldmine.” And, in true Meyer fashion, he seemed to have an obsession with getting the landscape and scenery right. “And any place where the characters were outside, I went and slept there because you have to see what the terrain is, what the plants are.”

But what’s most remarkable is how well Meyer infiltrates the brains of a Republican woman. The Jeanne character wasn’t always so complex. According to his editor at Ecco, Dan Halpern, he spent a year after selling the book revising her. To listen to Meyer—and to hunt with him—you wouldn’t guess he had it in him. “Ah, sheeit girl,” he said in his Texan accent, delighted, when I complimented him. “Just tried to imagine having a vagina!”

If Meyer is worried about one thing, it’s how Native Americans are going to respond to his book. He told me that Louise Erdrich read the book “and was like, ‘Look, I love this but it made me feel kind of schizophrenic because of the amount of violence done by Native Americans.’” Meyer continued: “She was like I know this is really PC but I’d feel better about this if you were Comanche. I didn’t say this, but, you know, that is insane, because this is historically accurate.”

The character of Eli, the mythmaker, is the book’s response to reconciling this kind of otherness. Eli is a Texan who happily grows up with the Comanche that kidnapped him and killed his family. He later becomes a Texas Ranger who hunts Indians. He’s a cattle owner during the twenty-year period in which that’s profitable, and an oilman after that. He’s “incredibly physically and mentally and emotionally resilient,” Meyer said. “A person you always want on your side.” Are they morally sound? That’s another question. But Eli controls his own future. Just like Meyer.

Of course, the publicity machine is behind The Son, too. Ecco paid Meyer a $1 million advance (after Meyer dumped his first agent Esther Newberg, allegedly because she advised him to settle for less). Eric Simonoff, the agent who sold American rights for The Son and whose clients include Bill O’Reily, Edward P. Jones, and Jhumpa Lahiri, told me, “I recognized it was one edit away from being a masterpiece, and I didn’t, frankly want to screw anything up.” Dan Halpern, the esteemed founding editor of Ecco who bought the book, told me, “I said to [Meyer] in the very beginning, ‘Just do me a favor and don’t f— this book up. Make sure the rewrite works.’ . . . I didn’t have to worry about his feelings.” Fortunately, as Simonoff said, Meyer is “incredibly confident in his ability … in a really unusual way.” Or as Meyer said of himself, “I have an outsized ego.”

By the Colorado River, Pinkard threads rope through the eyes that he cut between the knuckle and tendon of hog’s hind legs and then he hoists the boar up on the branch of a Mexican Blue Oak. Pinkard skins the thing with swift, darting strokes, until all the skin is hanging around the hog’s neck like a gravity-defying cape, and then Pinkard uses both hands to unscrew the head around and around as if it were the wheel of a vault until it is dangling by one tendon, which he hacks. What’s left hanging from the tree looks like a 170-pound pastrami roll with arms and legs. That is until Pinkard runs Meyer’s blade down his stomach. Lungs, intestines, stomach, liver, burble out of the seam and plop onto the verdant green grass—a landslide of balloon-like organs the shades of Jordan almonds: pastel purples, pinks, and blues.

After the field-dressing process (it’s funny that this isn’t called undressing), we hop into Meyer’s gray 4×4. There’s a brown cooler full of raw pork in the back, and Meyer is in a good mood. He reverses his truck faster than anyone I’ve ever seen: He stands up against his chair, the rigid human hypotenuse to his seat, craning his neck to look backwards. He calls it “offensive driving” and he learned it (along with J-turns and how to stake out a house) at one of the two summers he spent doing Blackwater training. “I had a sense that the wars were going to play in the new book, which was wrong,” Meyer tells me. Regardless, he applied to Special Forces with a letter of recommendation from a General and two colonels. He believed that as a supporter of the war in Afghanistan he was obligated to fight in it. Plus, what an elite institution. It would have cost him six years of active duty, and eight years of allegiance. He would have been with them until he was 46. Kevin Powers thought it was silly, but said he understood. His editor at Ecco hated the idea and thought it was crazy. But none of that mattered. The Pentagon, at the last moment, denied Meyer’s request for an age waiver (the cut-off is 35). Perhaps, one might guess, they did this because he is a writer.

I ask Meyer whether he’s going to buy land in Texas, and he says the paranoid part of him wants to make sure he’s not tied down to anything. That in the event his career takes a downturn—which he doesn’t expect—he won’t have financial obligations. He’s not even quite sure he wants to stay living in Austin part-time. I ask him where he’d move.

“Maybe New York,” he says, which is where he currently lives part time. “It matters more to be a writer there. Any kind of intellectual pursuit, you sort of get brownie points from society…. Though that’s sort of happening here now. I’m starting to get on the lists for fancy places,” he says.

But no matter where he ends up, this book should win him recognition as an honorary Texan, which is something he already epitomized, anyway. After all, being a Texan is all about picking yourself up by your bootstraps, being resilient, ambitious and iconoclastic: the high school drop out who attends an Ivy, the novelist working at an investment bank, the gun enthusiast in an MFA program, the New Yorker twenty-under-forty writer who loves Blackwater training. Plus, while you might not be able to judge a book by its cover, you can judge a person by the contents of their suitcase, and when Meyer lifts off, I know what the x-ray machines will see: 20 pounds of frozen feral hog.

Read an excerpt from The Son here.

- More About:

- Books