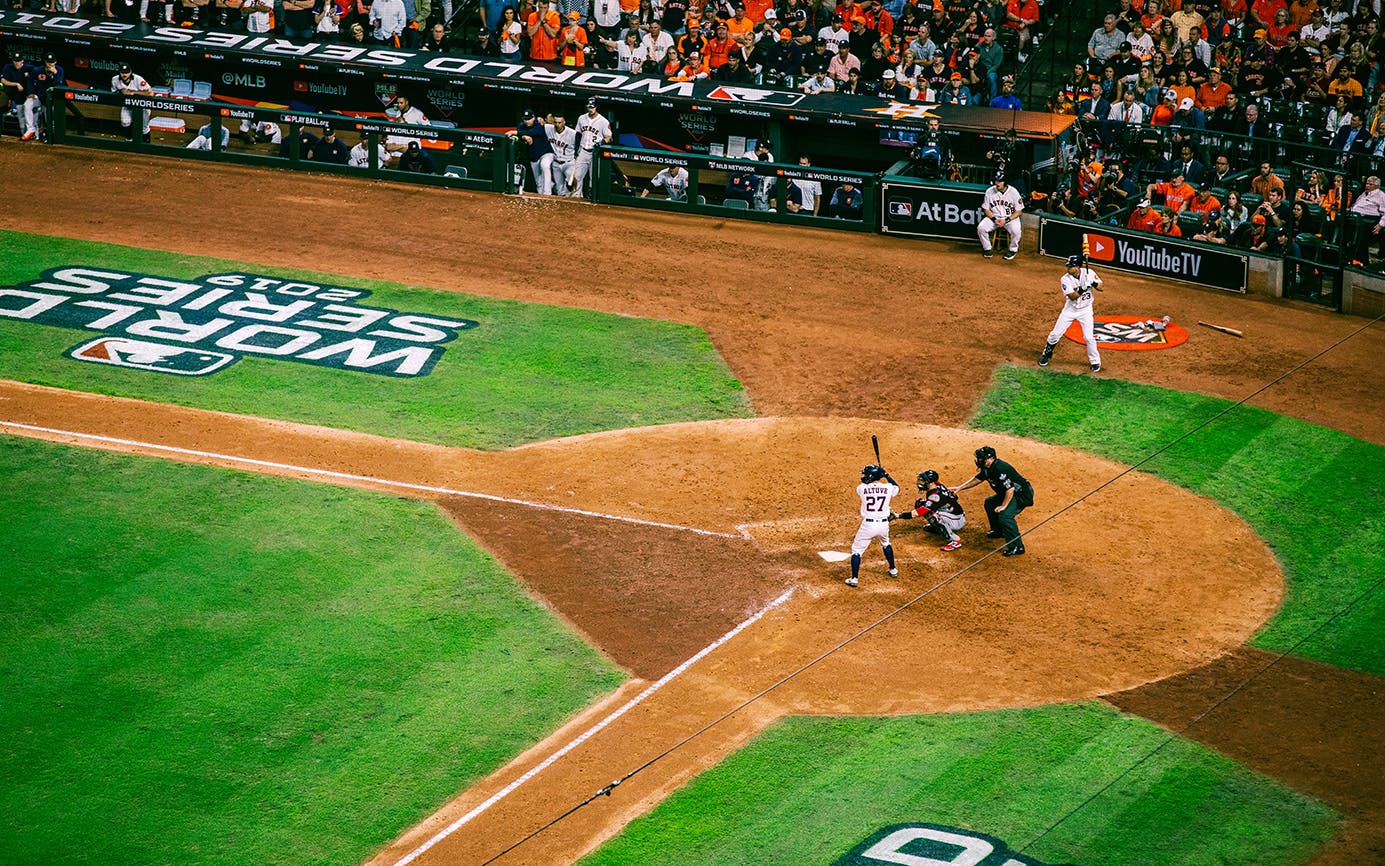

A day before the Houston Astros organization found itself embroiled in scandal, a locker room photo of the team’s four core position players—Jose Altuve, Alex Bregman, Carlos Correa, and George Springer—circulated on Twitter and fan forums. In the picture, the quartet are draped over one another. Springer’s arms are around Correa, who’s leaning on Bregman’s knee. Altuve’s cheek is pressed into Springer’s shoulder. They look like childhood best friends watching a movie at a sleepover.

We soon learned that in that same locker room, just after Houston had claimed the American League pennant earlier this month, assistant general manager Brandon Taubman had unleashed a heavy dose of toxic masculinity on a group of female reporters. He pointedly celebrated the team’s acquisition of pitcher Roberto Osuna, who’d previously been suspended by Major League Baseball for a domestic violence incident, as key to the team’s victory.

Sports Illustrated’s Stephanie Apstein reported it. Team management at first denied that the incident had happened, but was eventually forced to apologize and to fire Taubman. But the damage was done—for much of the country, the Astros had taken a heel turn and become the villains of the 2019 World Series. If you weren’t already predisposed to root for Houston, you probably weren’t upset to see them lose the championship in a decisive Game 7 to the Washington Nationals on Wednesday night.

Sports franchises are complex networks of people, not homogenous hive minds (even if Houston’s stats-driven decision-making aspires to be something like that). We shouldn’t write off whole teams any more than we do everyone who works for a particular business, or who lives in a specific state or nation. But organizations do have the power to affect the behavior of their constituent parts, and for that we must absolutely hold them accountable. We need rooms full of Stephanie Apsteins. We need voices of criticism moving us forward when we err. I say that as a rabid Astros fan deeply frustrated by the team’s responses in the wake of Taubman’s actions.

My own conflicted feelings aside, I wondered if other fans were confronting their own existential questions about the cost of team management’s bottom-line thinking. In the upper deck of Minute Maid Park just before Game 6 got underway Tuesday night, I spoke with a dozen or so groups of people to gauge their feelings. About half said they weren’t aware of the Taubman situation, or hadn’t followed it closely enough to know what was going on. Several people mentioned Taubman’s “language” or suggested that he should have phrased his comments more appropriately, but that never seemed to be the issue. Jan Jones, a fan who has been attending Astros games for several decades, believes that “we are so politically correct in our environment right now, it’s ridiculous,” and says she didn’t see Taubman’s actions as “a threat to women.”

But some people at the game had stronger feelings. Alberto Almada, an El Pasoan who moved to Houston five years ago, says that the whole episode gave him a “different take” on how the Astros were being run as an organization. He compared the team’s management to a “bro culture” or a “frat party.” Yet Almada hasn’t given up his fandom and says he still loves the players, despite his disappointment with the front office.

Chris Lippincott, now an Austin resident but who lived in Katy through Hurricane Harvey and says his family was rescued by the Cajun Navy after the storm, emphasized how much the team’s World Series championship meant to him and his grandmother in 2017. The Astros were then a beaming north star on the road to recovery. He’s “disappointed” with what feels like a shift in team culture. He pointed out how the Astros, under previous ownership and management, had parted ways with Julio Lugo when he was accused of domestic violence in 2003.

Life-long Astros fan Allison Miller said her experience of this year’s World Series was undoubtedly soured by the scandal. Taubman’s actions hit a nerve, she says, that resonated with her own experiences as a professional woman sometimes told by men that she doesn’t belong “in sometimes violent ways.” The Astros’ initial statement defending Taubman frustrated her even more than the incident itself. Like Lippincott, she has loved the Astros through winning and losing seasons, and being able to cheer for them in good conscience means more than anything else.

Still, the focus in the upper deck at Minute Maid Park this week remained on baseball. When asked about Taubman, many attendees were aloof. Regarding Osuna, fans like James Watkins described him as simply “a great pitcher.” Even Holly Bermudez, who says she personally dislikes Osuna, encapsulated the general mood by saying, “I was kind of nervous because I didn’t know if it was going to affect the team and the morale. I don’t want anything negative to affect us winning.” Bermudez’s partner, Chris Castillo, added that Taubman “did a disservice to the team and to the fans too.” He hated seeing the national press focus on a version of the Astros that isn’t the team he knows and loves.

I can relate to that. The Astros were defeated by a scrappy roster of players whose buoyant celebrations in the dugout resembled their own in 2017. The Nationals faced five elimination games, trailed in all of them, and came back to win each one. The victory they’ve pulled off is admirable.

The Astros—whose slogan once was literally “Root for the good guys!”—have made it more difficult to see them that way, and now they’ve lost the World Series as heavy favorites.

Neither heroes nor underdogs nor champions, Houston is left with an identity crisis. Who will the team be next season, and for the seasons that lie ahead? They’ll still have that joyous core four—Altuve, Bregman, Correa, and Springer—as well as other exciting young players and dominant pitching. All is not lost, but the team has work to do this offseason if their star is going to rise again sooner rather than later.

This article has been updated to correct a misstatement that the Astros 2017 World Series win had meant a lot to Chris Lippincott’s elderly mother. It was his grandmother.

- More About:

- Sports