The word “opera” often conjures images of larger-than-life women in Viking hats, or a Pavarotti-like tenor belting out an impossibly long note—all while wealthy, white audience members watch through binoculars from a balcony. While there’s certainly some truth to these tropes, contemporary works increasingly seek to broaden what opera can be and whose stories it can tell. One of these is the Houston Grand Opera’s production of The Snowy Day, which premieres December 9.

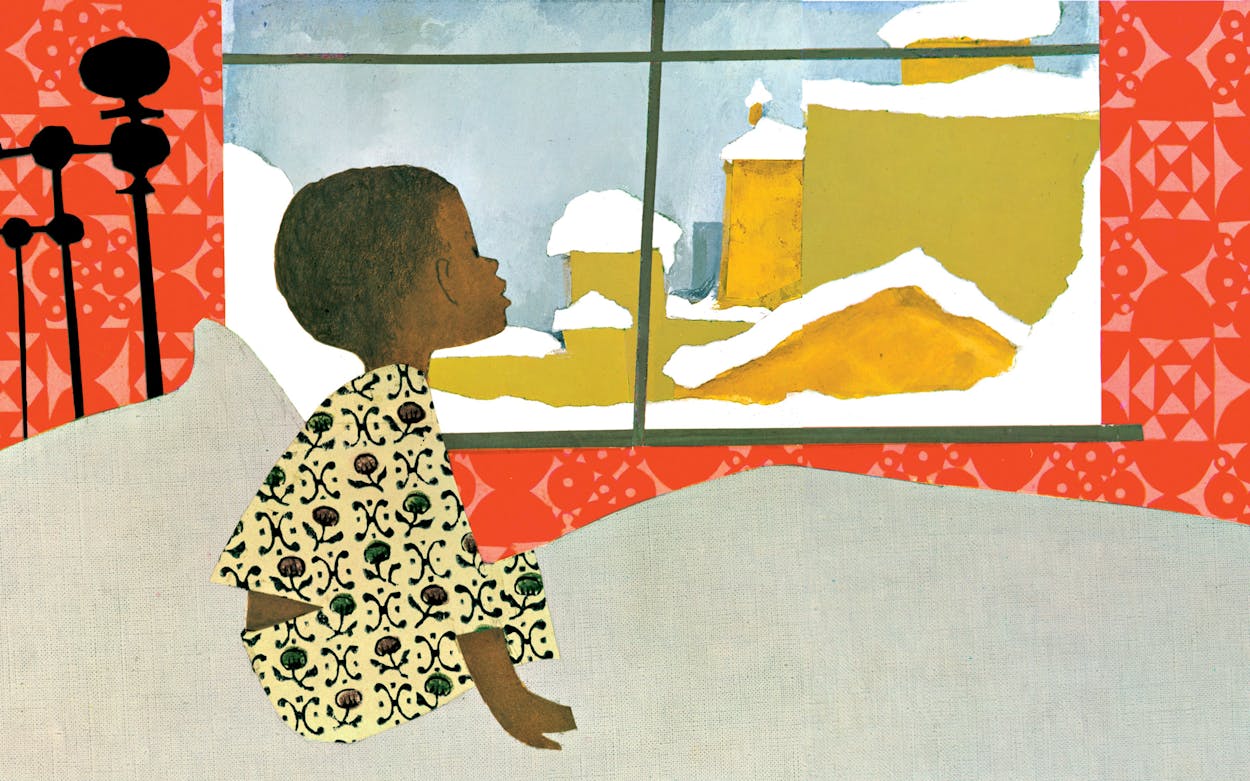

You might already know the story from Ezra Jack Keats’s colorful children’s book of the same name, originally published in 1962. While it wasn’t the first children’s book with a Black protagonist, it was the first major picture book to break the color barrier in children’s literature, quickly becoming one of the most popular and most accessible titles on the market. Serving as the inspiration for postage stamps and an animated holiday TV special, it is the most checked-out book at the New York Public Library. The seemingly simple story centers around a small, brown boy named Peter who wakes up to find the first snow of the season in all of its glistening magic. Peter is so enamored with the snow that he tries to take a snowball home as a keepsake, only to be confronted by the harsh reality of seeing it melt the next morning. He learns a lesson about impermanence and heads out for another day of sledding and making snow angels. The story was an instant classic of timeless discovery and childlike innocence. It was also a chance for Black children across the world to see themselves represented in mainstream literature. Two of those children grew up to become the creators of this new operatic work: composer Joel Thompson and librettist Andrea Davis Pinkney.

Thompson fell in love with Peter’s story while growing up in the Bahamas with his Jamaican parents. His mother, a teacher, brought home copies of the book in both English and Spanish. “It was fascinating for two reasons: I saw a child who looked like me, and I had never seen snow,” he says. “They were both foreign things that were equally full of wonder.” Pinkney was introduced to the tale even earlier. She recalls her parents telling her that it was the very first book they placed in her nursery. “I remember sleeping with it like it was a pillow,” she says. “I was embracing the brownness of Peter; I was embracing seeing myself represented on the cover of that book.”

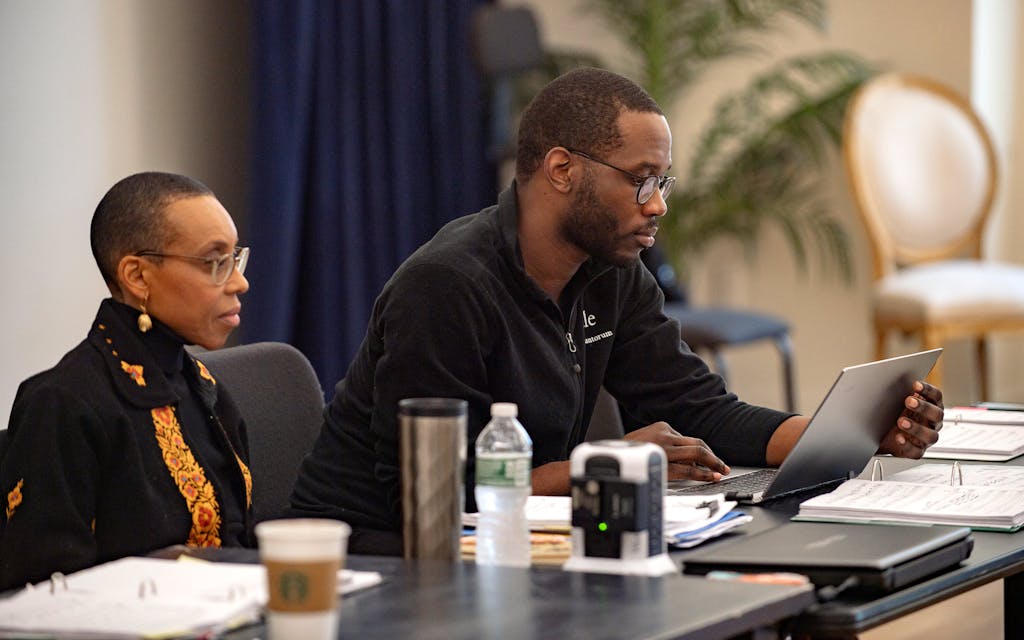

Before they began work on the project in 2019, neither Thompson nor Pinkney had tried their hand at opera. But both have spent their careers telling inclusive stories. Thompson, a doctoral candidate at Yale and an acclaimed composer, conductor, and pianist, is best known for his stirring 2015 choral work Seven Last Words of the Unarmed. The painstakingly beautiful arrangement, centered around the death of Michael Brown and the rising racial tensions caused by police brutality, won the 2018 American Prize for Choral Composition. After that and similarly weighty projects, he was ready to focus on joy rather than trauma. “My personal aim was to get in touch with my own inner child,” Thompson says. “I wanted to look at the world with wonder instead of fear.” That perspective is itself a form of resistance.

Similar themes appear in the work of Pinkney, who is an award-winning author of close to fifty children’s books. In such works as Sit-in: How Four Friends Stood Up by Sitting Down, Bright Brown Baby, and Sojourner Truth’s Step, Stomp, Stride, she celebrates historic Black voices and makes way for a multifaceted representation of current Black life. Pinkney homed in on the team’s desire to create authentic moments that highlight what is true to Black culture without even naming it as Black. In one scene, Peter’s parents prepare him to play outside by covering his skin in a protective layer of Vaseline. This is a small, subtle moment, but one that will resonate with Black audiences who grew up with the same routine. Pinkney also insisted that the opera include a scene in which Peter’s mother prays for him (though this doesn’t happen in the book). “Keats wasn’t religious,” she says. “But every mother prays for the well-being of their child, whether religious or not.” Thoughtful touches like this one play a huge part in transforming the 316-word original text into a one-hour production to remember.

In order to accomplish this, the duo had to reimagine Peter’s world to create a full experience for the audience. This was more challenging than you might think, since there is no dialogue in the original book. How to endow silent characters with voices? “Our first consideration was how to bring the story to life and make it theatrically vibrant,” says Pinkney. “The libretto seeks to give voice to Peter’s inner world and the people that inhabit that world.” The simple set centers on the window from which Peter views the world. The music moves through segments of timpani and flourishes of strings and light percussion, all while staying true to Keats’s original story. The libretto expands Peter’s world by adding characters who aren’t in the book, such as Peter’s father. “We thought it was important to show an intact African American family,” Thompson says. Additional characters, such as Peter’s friend Amy, who is Latina, and neighborhood bullies Jasper, Tim, and Billy round out the cast. The result is a story that steers away from stereotypes and feels universal.

Still, Pinkney and Thompson didn’t make this piece in a silo unplugged from the current issues of the world. “We are at a moment of racial reckoning in this nation. We couldn’t ignore that,” Pinkney says. “Mama’s Misgivings,” an aria for Peter’s mother, gives the audience a chance to wrestle with the reality of a young Black boy venturing out into the world alone in a red hoodie. The song doesn’t address the threat of violence directly, but lyrics like “Mama’s eyes are watching this world” echo the same fear for Black Americans’ safety that was felt after the shootings of Trayvon Martin in 2012, Tamir Rice in 2014, and countless others since. But where other narratives would center on this trauma, The Snowy Day offers a moment to push through it and find something more magical. Maybe that was Keats’s intention all along.

Pinkney and Thompson’s collaboration arrives at an exciting moment for opera, as diverse talent finally enters the stage. New York’s Metropolitan Opera recently premiered Terence Blanchard and Kasi Lemmons’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones, the Met’s first opera led by a Black composer and librettist team. “I want to believe that opera can be a space where we can exercise empathy, in both the creative side and inspiring it in our audiences.” says Thompson. “Peter gets to awaken to a new day.”

The opera world just might be ready for this kind of awakening. Projects such as The Snowy Day are changing the outdated representations that are familiar from works like Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. Reflecting on the problem and the progress that is still needed, Pinkney compares it to living in a world without windows or mirrors. “The first consequence of this world is that you forget what I look like. You can’t see yourself represented and after a while you don’t really exist. If the windows are blocked off, you can’t look out and see others, and they can’t look in and see you,” she says. “That’s how marginalization happens. That is why we need people of color working in opera, so we can see ourselves and others—to let the light in.”

In another pandemic winter, that message feels especially timely. “This story is an antidote to fear, an antidote to isolation,” Thompson adds. In a moment where the world may need healing more than anything, The Snowy Day gives us a quiet moment to cast our fears aside and simply play in the snow.

- More About:

- Houston