This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

My brother John, who resides in Brooklyn, called me this past December to tell me that he had just finished weeping in a Manhattan sports bar. The Houston Oilers had won their ninth consecutive game after a 1–4 start, beating Pittsburgh 26–17 in Three Rivers Stadium to clinch the American Football Conference’s Central Division championship only five days after the suicide of Oilers defensive tackle Jeff Aim. John had watched the game on a big screen, surrounded by thunderstruck Steelers fans, and the experience was just too much for him. After the final gun sounded, he ambled off to the men’s room, bawled unashamedly for a few moments, and then returned home to his wife.

I had watched the same game, alone in an unlit room, and experienced a similar emotional breakdown. True, the Oilers had won. True, they have won fabulously this year and are expected by many to face the Dallas Cowboys in the Super Bowl. True, a follower of the Cowboys would not have behaved this way. But Houston fans, like my brother and me, are entangled in a relationship with their professional athletes that goes beyond dysfunctionality and into the dark realm of the pathological. We love our Oilers, Astros, and Rockets as we would a dashing con artist who woos us annually with diamonds, abandons us at the altar, and returns a week later with tickets for two to Paris. How could we fall so hard so often? Look it up: No other city in America endures three pro teams that have each come as close to a championship season as have the Oilers, Astros, and Rockets, and yet never delivered. Our teams are not studies in futility. They are heartbreakers, pure and simple. And seasonally the heartbroken return, always with skepticism, but finally too smitten to resist the latest round of grand overtures.

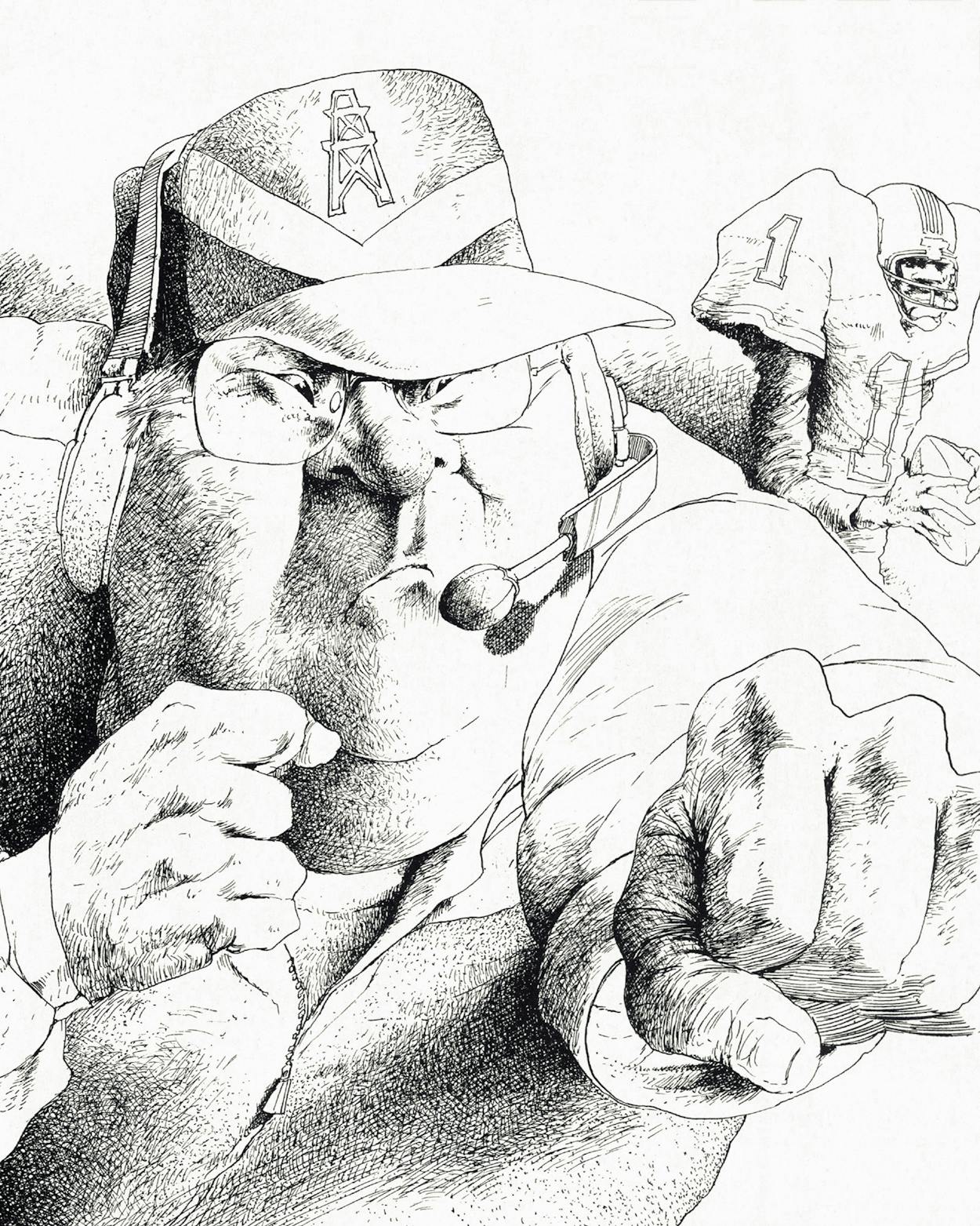

The turn of this year marks another season of recklessly high hopes. The Houston Rockets won their first fifteen games, tying the best start in NBA history. For the first time in at least six years, opponents refer to the Rockets as a team, rather than a hodgepodge supporting cast for the NBA’s best player, center Hakeem Olajuwon. Hakeem, dare we dream? The Astros, following a disappointing 1993 season, have hired fiery manager Terry Collins and acquired nerve-shattering relief pitcher Mitch “Wild Thing” Williams—at last, they look like a team with enough desire to match its talents. Then there are the Oilers. By the time you read this, we will both know whether Houston’s football team has atoned for its 41–38 choke in Buffalo a year ago or instead fashioned a miserable reprise. After Buffalo, the Oilers were a national joke—and so, by extension, were we. But the moment owner Bud Adams hired defensive coordinator Buddy Ryan, the fans were back in droves. The Oilers showed their gratitude with a 1–4 start, and the follies did not end there. When offensive tackle David Williams missed game six so that he could attend the birth of his son, columnists like the New York Times’s Anna Quindlen ridiculed Oilers management for punishing Williams, bringing additional shame to us all. Later still, the rest of the world snickered at the Oilers when Buddy Ryan threw a punch at offensive coordinator Kevin Gilbride on the sidelines in the middle of a game. Oilers fans have seen this sort of foolishness in earlier years—but this season, our patience has been rewarded. The Oilers are a franchise-record 12–4, jock pundits everywhere are confidently predicting an all-Texas Super Bowl . . . and, Lord, how we yearn to believe that this is the year of deliverance, rather than just another vicious tease.

We were set up early, we Houston fans, by teams that softened us to the concept of losing. I remember, as a six-year-old boy in 1963, fidgeting under the summer heat at Colts Stadium, wearing an oversized Colt .45s baseball cap, while my grandfather, a season-ticket holder, hollered, “Aspromonte, you run like you’ve got a piano on your back!” I later remember my teenage cousin Mike mimicking the ineptitude of Oilers quarterback Don Trull by staggering punch-drunk around the back yard and heaving passes into the trees. I remember my uncle’s announcing to the family that he and a few business partners had purchased the San Diego Rockets and were moving the team to Houston—and then I remember seeing the Rockets get freshly slaughtered in Hofheinz Pavilion and thinking to myself, “Just what this city needs.”

True, the Oilers contended for the American Football League crown in 1967, and the Astros finished second in the 1969 National League pennant race. But these were only mild flirtations with triumph. Houstonians grew accustomed to rooting for losers and embraced them in a way few other cities would. Well into the seventies, Houston remained a raw and somewhat clumsy town, a place filled with daredevil novices looking to score big. Some of them wore boots, others wore cleats. Prosperity was every Texan’s dream, but a failed dreamer in Houston didn’t have to go underground. He could stick around, and a few of us might even congregate to cheer his next bumbling endeavor. How could we have known that this safe, sweet relationship we had with our awful teams would evolve into something so tormented? How could Bum Phillips and Earl Campbell have done that to us?

From 1975 through 1980, Bum’s Houston remained in a state of holy agitation not unlike Khomeini’s Teheran. I will always remember the closing months of 1979 as a time when every large hairy man in the city wore powder-blue clothing in broad daylight; a time when otherwise tasteful souls bought out the initial pressings of two of the ghastliest singles ever recorded: “The Oiler Cannonball,” sung badly by center Carl Mauch, and “The Oiler Fight Song,” written by a mathematician and sounding like it. No Houstonian talked about anything else. Bum could have made us drink Guyana punch. Instead, his players were steamrollered by the great Pittsburgh Steelers in the AFC championship, just as they had been a year before. But we were too far gone to let go. To an Astrodome late-night pep rally crowd of 70,000—more people than had actually attended the game in Pittsburgh the previous afternoon—the Oilers coach delivered his famous January 7, 1980, proclamation: “One year ago we knocked on the door. This year we beat on the door. Next year we’re going to kick the son of a bitch in! ” How I wanted to be in the ’dome that night. Instead I was on a plane to Saudi Arabia, where I spent the next few months driving a truck filled with refinery valves through the oil fields of the Middle East, a pagan among Muslims with a Columbia blue derrick emblazoned on the front of my shirt. My parents sent me clippings, and in the desert I read how Bum had rolled the dice in classic Houston fashion. First he brought in an aging gunslinger, former Raiders quarterback Kenny Stabler, and then he mortgaged the team’s future by trading three high draft choices for Raiders tight end Dave Casper. The 1980 season would be all or nothing, and I returned home to find . . . nothing. The Oilers had unraveled early in the playoffs, precipitating the firing of Bum Phillips and the dissolution of the Luv Ya Blue era. Yet that very October saw the Astros come within a couple of runs of winning the National League pennant. Seven months later, an overachieving Rockets team somehow overcame a 40–42 regular-season record to battle the Boston Celtics for the NBA championship. The Rockets lost the series, 4–2, but that was enough to stoke the old embers. The city was hooked again, taking the very bad with the almost good enough.

I moved to Tokyo in 1986 just after watching the Twin Towers of Olajuwon and Ralph Sampson devastate the Los Angeles Lakers before finally falling to Larry Bird’s Celtics—and we just knew, didn’t we, that in ’87 the Rockets would take it all. Months later, I watched on Tokyo tape-delay as Mike Scott’s no-hitter brought the Astros to a National League championship showdown with the Mets. Again the good guys lost, yet only barely. Then came football season. The Oilers went 5–11 that year, despite owner Adams’ usual prediction that the team would be playoff-bound in 1986. My mother sent me the game videotapes, which I received a week after the fact. Warren Moon took a savage beating every game. The tapes were like underground snuff movies; I watched them with horror and tried to think of nice things, like the Rockets and the Astros. Yt those teams flopped miserably the following year, while the Oilers ascended, taking us with them on another series of cruel rides.

Kenny Stabler, Elvin Hayes, Don Sutton. Archie Manning, Moses Malone, Nolan Ryan. Warren Moon, Ralph Sampson, Mike Scott. For every season there came a new gladiator and soaring spirits. Ah, but there was always another wave of disaster coming over the horizon: the career-ending stroke in 1980, of J. R. Richard, who was as dominating a young pitcher as the major leagues had seen in years; the demise of brilliant shortstop Dickie Thon after being felled in 1984 by a pitch that caved in his eye; the banishment of Rockets guards Lewis Lloyd and Mitchell Wiggins after each tested positive for cocaine in 1987; the 1985 through 1989 tragicomic reign of Oilers coach Jerry Glanville, whose grandstanding buffoonery inspired opposing teams to roll up scores and take shots at Warren Moon’s head; Astros owner John McMullen’s refusal to meet Nolan Ryan’s contract demands in 1988, resulting in the Hall of Fame pitcher’s departure; the suspension by Rockets general manager Steve Patterson, at the close of the 1991–92 season, following speculation that Olajuwon was faking injury; and finally, that infamous afternoon in Buffalo only a year ago, when the Oilers blew a 35–3 lead and instantly lost every fan they ever had, until the following season.

How could we know that the safe relationship we had with our teams would evolve into something so tormented?

Why do these things happen to Houston teams? I have heard a hundred theories advanced, among them unsupportive ownership, inept management, a lack of player leadership, lousy stadium facilities, and the effect of Houston humidity on ball movement. None of them holds up. The New York Yankees, for example, have won with meanspirited owners, bad managers, and selfish players, just as they have lost with more innocuous ownership, crafty managers, and upright talent. Champions are champions because they prevail over their own demons. Of course, the Dallas Cowboys have suffered embarrassing episodes—wide receiver Lance Rentzel’s indecent exposures, Hollywood Henderson’s drug problems, the disgraceful sacking of coach Tom Landry, and the recent gridiron misadventures of Leon Lett—to say nothing of the hapless Mavericks and the roller coaster Rangers. Yet the low moments have done no damage to the city’s collective psyche. Dallas fans adore their winners and despise or ignore their losers. There are exceptions, of course, and I consider those people to be prospective Houston converts. Whatever else I may have done or failed to do for my ex-wife, Judy, she is now an Oilers season-ticket holder. During the Cowboys’ Super Bowl season last year, a relative sidled up to Judy and seductively asked, “When you look deep into your heart, what is it you see? A derrick? Or . . . a star?” She remains with us, as does my brother in Brooklyn. We are all aboard the runaway train. We don’t know where we’re going, but where would we be if we jumped off?

- More About:

- Sports

- Business

- TM Classics

- Houston Rockets

- Houston Oilers

- Football

- Houston