There’s one moment in nearly every Asleep at the Wheel show that best displays the band’s genius, but if you’re spinning on the dance floor as fast as you’re supposed to, you might miss it. Typically it comes about halfway through a set on the nights when the longtime Austin band covers “Choo Choo Ch’Boogie,” the jump blues classic made famous by Louis Jordan & His Tympany Five back in 1946. But the Wheel doesn’t play “Choo Choo” like Jordan did, opting instead for its signature style, western swing, the big band jazz–country hybrid that the band’s heroes-turned-mentors Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys sent out to the wider world from Dust Bowl–era dance halls. The Playboys’ great achievement was to expertly play Count Basie–style swing on stringed instruments, keeping horns in the mix but relying on electric guitars, steel guitar, and fiddles to carry the load. Like jump blues, it’s dance music, but above all, it’s fun.

Wheel fans come to shows expecting a good time. Front man Ray Benson, the seventy-year-old six-foot-seven long-haired dope smoker who formed the band in rural West Virginia in 1970, is the madcap ringmaster, scat-singing lyrics, picking a blistering electric guitar, calling for solos, and cracking wise, just like Wills once did. And the players, of whom there have been nearly a hundred, have all been topflight musicians, proficient at licks that swing, sway, or bounce, depending on what a song requires.

The current iteration of the band has gone so far as to institute a game they play onstage. Before a gig, one member will pick a song to quote during the show, maybe the theme from The Flintstones or The Andy Griffith Show. The player who sneaks a riff from that song into the most solos is deemed the winner. “That’s the band’s deal,” says Benson, “and I like it because it keeps them listening to each other. That’s the whole thing with improvisational music.”

But the special moment in “Choo Choo Ch’Boogie,” while it also involves a quote from a song, is more of a set piece. Benson’s not sure when it was cast in stone or by whom, though he assumes he did it himself. The Wheel first recorded “Choo Choo” not long after moving to Texas, for its 1974 sophomore album Asleep at the Wheel. A bit later, Benson, an omnivorous musical autodidact, was studying Thelonious Monk, and in particular “Straight, No Chaser,” a typically knotty Monk tune. “I remember living out in Pedernales and really sweating it trying to learn that song. So I must have just dropped it into ‘Choo Choo.’ And what happens is, somebody plays something, does it twice, and then it sticks.”

Ever since, the Wheel’s live “Choo Choo” has run like this: Benson opens with his rich basso profundo—“Headin’ for the station with a pack on my back / I’m tired of transportation in the back of a hack.” He races through the first two verses, then turns the song over to the band for meaty sixteen-bar solos, first from the steel player, then fiddle, his own guitar, and sax. On the way out of that section, the players start “trading fours,” or swapping dizzying four-bar mini-solos, before Benson plucks a climbing chromatic scale that lifts the song an octave and signals the shift to “Straight, No Chaser.” Seamlessly, the band drives through Monk’s main melody line twice, an interlude lasting all of thirty seconds, then dives back into “Choo Choo” and Benson’s vocal—“I really love the rhythm of the clickety-clack / So take me right back to the track, Jack”—and out.

If that sounds like music nerd–speak, it is. But the feat described is hard for even the nerdiest musicians to master. Jason Roberts, the Wheel’s lead fiddler from 1997 to 2014, who now fronts the modern incarnation of Bob Wills’s Texas Playboys, had to learn “Straight, No Chaser” before joining the band, as did Cindy Cashdollar, who played steel for the Wheel from 1992 until 2000 before going on to record with artists like Bob Dylan, Van Morrison, and Rod Stewart. Neither had an easy go of it. “The deal is,” says Benson, “if you can’t play ‘Straight, No Chaser,’ you ain’t gonna get in the band. First tryout, you’re going to do ‘Choo Choo,’ you’re going to have to play a great solo, and then you’re going to have to drop in ‘Straight, No Chaser.’ That’s a pretty good entrance exam.”

Having spent his adult life making all that look easy, Benson knows why it works. “Musicians hear that, recognize Monk, and say that’s what makes the Wheel cool. Everybody else says they love that song because their kids love it; it’s about a choo choo.”

If you grew up spoiled on Austin’s music scene, you’d be forgiven for thinking of Benson and the Wheel as local musicians, even with their eight Grammy wins. And if you read Benson’s 2015 memoir Comin’ Right at Ya: How a Jewish Yankee Hippie Went Country, or the Often Outrageous History of Asleep at the Wheel and noted all the bold-faced names in the band’s orbit—Van Morrison, Willie Nelson, Huey Lewis, Dolly Parton, Merle Haggard, Bob Dylan, et al.—you might think of Benson as Texas music’s Zelig. But in fact, those weren’t right-time, right-place run-ins with brighter lights; those were relationships with peers. The Wheel is that good at what it does, and its contribution to American music is that important. George Strait, who opened for the Wheel when he was starting out, and who continues to return the favor by giving the band opening slots to this day, pops up repeatedly in the book. “I try to include the Wheel anytime I can at my shows,” Strait wrote in an email. “They’re good friends, and they’re exposing people to authentic western swing. Not a lot of people do that, especially not as good as them. They keep Bob Wills’s music alive.”

Why, then, was the band’s fiftieth anniversary last year not a bigger deal? In early March 2020, Benson was assembling the band in his home studio to record an anniversary album, with a documentary film crew on hand to capture the effort. His two cofounding band members, steel guitarist Lucky Oceans and drummer-vocalist–primary songwriter Leroy Preston, had tickets to fly in from Fremantle, Australia, and Vermont, respectively, to record. And a commemorative Wheel alumni tour was slated to kick off with Benson’s annual birthday show at South by Southwest, a reliable conference highlight, owing in part to the big-name surprise guests that he books each year. Last year’s famous friend was to be John Prine.

Then the pandemic struck. On March 6, 2020, SXSW was canceled. Soon, the city shut down, and the Wheel’s plans were put on hold. The same month, Benson was diagnosed with COVID, a fortunately mild case from which he managed to recover. Tragically, Prine caught it too and did not survive.

“Let me just say this about the Wheel’s whole fifty years,” says Benson. “We have survived despite amazing odds against us, in many ways: (a) the music we play, (b) the people we are, and (c) let’s see—how many tragedies have Asleep at the Wheel encountered?” Then he half laughs as he ticks off instances of utterly wild happenstance. On September 11, 2001, the band was in Washington, D.C., to perform that evening on the White House South Lawn. The gig was canceled. In May 1980, it happened to be playing Spokane, Washington, when Mount St. Helens erupted, trapping them in town for five days. A year before that, they played Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, while the nearby Three Mile Island nuclear reactor melted down. So, of course their fifty-year celebration was postponed by a plague. “I should have known that would happen,” says Benson. “I could have predicted the fucking pandemic. But I kept my mouth shut, hoping I was going to have a gig.”

Rueful jokes aside, the shutdown left Benson unable to play live for the first time in memory. So he holed up in his house outside Austin to wait out the plague.

He grew up Ray Benson Seifert in a suburb of Philadelphia in the fifties and sixties. There, he and Reuben Gosfield, his childhood best friend, soaked up sounds from eclectic Philly radio: rock, soul, gospel, and jazz. Benson’s first love was big band, and Gosfield’s was the blues, but they were into just about everything. For that matter, Benson could play just about any instrument; at one point, he and Gosfield formed a jug band that played Motown and surf covers.

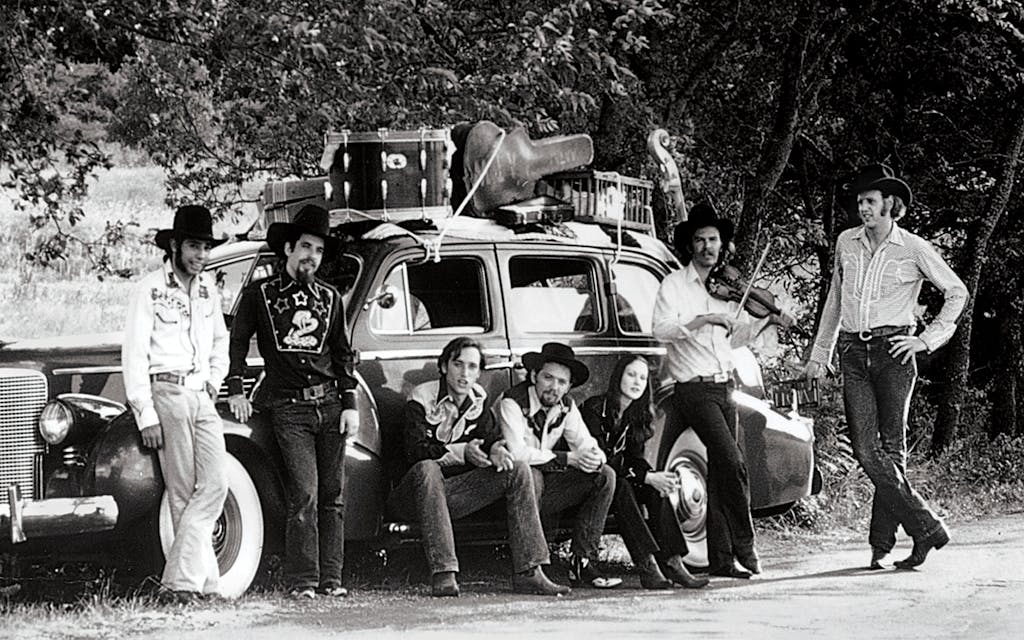

In 1970 Benson, Gosfield, and a new friend, Preston, a Vermont farm boy steeped in country music, moved just outside a tiny West Virginia burgh called Paw Paw. At that point, the three were pot-loving hippies tickled by the prospect of playing honky-tonks. So Benson dropped “Seifert” from his name, Gosfield changed his to Lucky Oceans, and they started booking gigs as Asleep at the Wheel, a name that occurred to Oceans while he was using the outhouse—but one that all three agreed was kinda cool. Soon they’d add another childhood friend of Benson’s, fiddler Danny Levin, and a female vocalist, Chris O’Connell, and then, in 1971, at the urging of Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen, like-minded players from the Bay Area, they decamped for Oakland, California. There they added a local boogie-woogie piano whiz named Jim Haber, who promptly changed his name to the far-sexier Floyd Domino.

At that point, the Wheel was a democratic outfit with multiple vocalists, and it played a lot of straight country. But all the members were enthralled by Haggard’s 1970 album, A Tribute to the Best Damn Fiddle Player in the World (or My Salute to Bob Wills), a hugely influential record that introduced young listeners to the out-of-favor dance music. Benson and Oceans already knew and loved Wills—as well as other swing pioneers like Milton Brown and Spade Cooley—but Haggard’s cleaner, modern recording let them learn licks they couldn’t from Wills’s old 78s. Quickly, swing became the band’s sound, and Benson, the only member with a business mind, the de facto bandleader. The Wheel secured a record deal in 1972 but started to sense that in Berkeley its act was a novelty. Then, in 1973, the band members met up with Willie Nelson. “Willie is the one,” recalls Domino, “who said, ‘You guys can play all the time if you move to Texas.’ ”

“We got to Austin and thought, ‘Are you kidding me? Rent’s a hundred dollars, pot’s dirt cheap, and there’s gigs on every corner? We can play redneck places and hippie places?’ ”

That was the pivotal moment. Austin offered its burgeoning cosmic cowboy scene, but the rest of the state was dotted with dance halls. “We got to Austin and thought, ‘Are you kidding me? Rent’s a hundred dollars, pot’s dirt cheap, and there’s gigs on every corner? We can play redneck places and hippie places?’ ” The move also reunited them with Levin, who’d wound up in Texas after opting not to go to California. But maybe most important, it put them in proximity to veteran Playboys, lions such as fiddler Johnny Gimble, guitarist Eldon Shamblin, and pianist Al Stricklin, who became their teachers, collaborators, and friends. “They all thought their music had been forgotten,” says Benson. “Then they saw us and were just amazed.”

Thus was the mature Wheel born, and though players have shuffled in and out—most of the original band left by 1980—Benson’s presence at the helm has ensured that the sound, if not the success, has been consistent. The band had a few hits through the seventies, followed by lean years during the early-eighties Urban Cowboy craze, when it survived, in large part, on Benson’s voice-over work. (His was the sonorous TV voice touting Budweiser and the McRib.) More middling hits came with a major-label record deal in the late eighties, and then, in the early nineties, Benson decided to lean all the way into championing Bob Wills.

“Everybody called us western swing,” recalls Benson, “even when they were reviewing New Orleans blues songs we’d played. So I started thinking—and I always quote the Bee Gees on this—‘How deep is your niche?’ ”

Beginning with 1993’s Tribute to the Music of Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys, the Wheel released a trilogy of duet albums celebrating Wills, featuring one-name superstars like Willie, Dolly, Reba, Lyle, and Vince, as well as old Playboys. “When we played ‘Blues for Dixie’ on that first Wills tribute record,” recalls Lyle Lovett, “Eldon Shamblin was on the session. And the song won a Grammy. So, I owe Ray a Grammy.” In 2005, Benson unveiled a two-act, Bob Wills jukebox musical, Ride With Bob, that he’d cowritten with screenwriter Anne Rapp. For the next eight years, he toured it on and off through nineteen U.S. cities, most notably performing it for President George W. and Laura Bush at Washington, D.C.’s Kennedy Center in 2006. More recently, the 2015 installment in the Wills trilogy, Still the King, reached number eleven on the country albums chart. In one sense, the Wheel was just doing what it’d always done, but now even more people were getting hip to the magic of Wills—and the notion that the Wheel was an institution itself.

This spring, with COVID seemingly on the wane, Benson jump-started the anniversary album sessions. He assembled a core band of Domino, Levin, current fiddler Katie Shore, longtime drummer David Sanger, and bassist Tony Garnier—on loan from Dylan’s dormant road band—to lay down basic tracks. Alums, including Oceans, Preston, and O’Connell, sent in parts recorded remotely. So did high-profile guests such as Willie, Strait, and Lovett, but their presence feels different from the “Ray’s Rolodex” quality of the earlier Wills tributes. These artists are all family.

The album they made, Half a Hundred Years, was released in October, and it registers as a long-overdue celebration of the Wheel itself. For one thing, after opening with the big-band twang of the autobiographical title song, Benson essentially cedes lead vocal chores to his former bandmates, just as he did during the early years. O’Connell shines on Basie’s “It’s the Same Old South.” Oceans gets his first-ever lead vocal assignment, on a swing song he wrote titled “I Love You Most of All (When You’re Not Here),” and Preston debuts “I Do What I Must,” a swing number he wrote way back in the seventies. Benson also reworks old favorites, such as the band’s only top ten hit, 1975’s “The Letter that Johnny Walker Read.” An inveterate pack rat, Benson also dusts off unheard archival jewels and drops them in as is, including a Willie duet on Tommy Dorsey’s “Marie”—an outtake from 2009’s Willie and the Wheel—and, most wonderfully, “Spanish Two Step,” an old-school, live studio recording cut with Gimble and Wills’s original fiddler, Jesse Ashlock, back in 1975. The result is a listening experience that feels a lot like flipping through a scrapbook.

Just as the album came out, Benson finally launched the reunion tour, which included an October 15 performance at Austin’s new, tony Moody Amphitheater. Nestled in the just-completed world-class reimagining of Waterloo Park and set against the backdrop of the ever-expanding city skyline, the venue is a far cry from the stages the Wheel played when it first came to town. As the show started, the audience behaved accordingly. But as the Wheel picked up steam, the crowd did too, welcoming the new songs and erupting at old Wills tunes. “Half a Hundred Years” was unveiled as a steel- and sax-heavy stomp. Katie Shore subbed nicely for Lovett’s harmony lines on current single “There You Go Again.” The fiddles stole the show on “Take Me Back to Tulsa” and “San Antonio Rose,” with Jason Roberts playing with a high whine reminiscent of Wills, and Danny Levin—his Open Road Stetson cocked at an aw-shucks crook on his gray Beatles mop-top—adding wry, bouncing licks that confirmed that yes, he’d learn to play in Philadelphia in the sixties, a place and time when Texas fiddle was considered ironic.

When surprise guest George Strait came out—surprising exactly nobody—the crowd rose to its feet as the Wheel shifted to crackerjack backing-band mode to support the King of Country on dance-hall favorites such as “Is Anybody Goin’ to San Antone” and his own hits, such as “Troubadour” and “All My Ex’s Live in Texas.” And then, with Strait and his wife, Norma, watching from the wings and dancers clogging the amphitheater aisles, Benson cranked things up yet another notch to close the show. On the penultimate number, “House of Blue Lights,” he juggled three beanbags, catching one on the brim of his hat.

There was no indication the audience even noticed. They were too busy shuffling, spinning, and dipping. Because that’s what you do at an Asleep at the Wheel show.

This article originally appeared in the December 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “How Asleep at the Wheel Keeps on Turnin’.” Subscribe today.