On September 11, 2001, Gary Tinterow was working as a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The museum closed briefly after the terrorist attacks—the first time it had done so since its founding in 1870. Tinterow remembers hushed meetings with colleagues, everyone reeling and trying to plan when and how to reopen. Now the director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, he’s experienced many of the same emotions since the museum closed its doors on March 16.

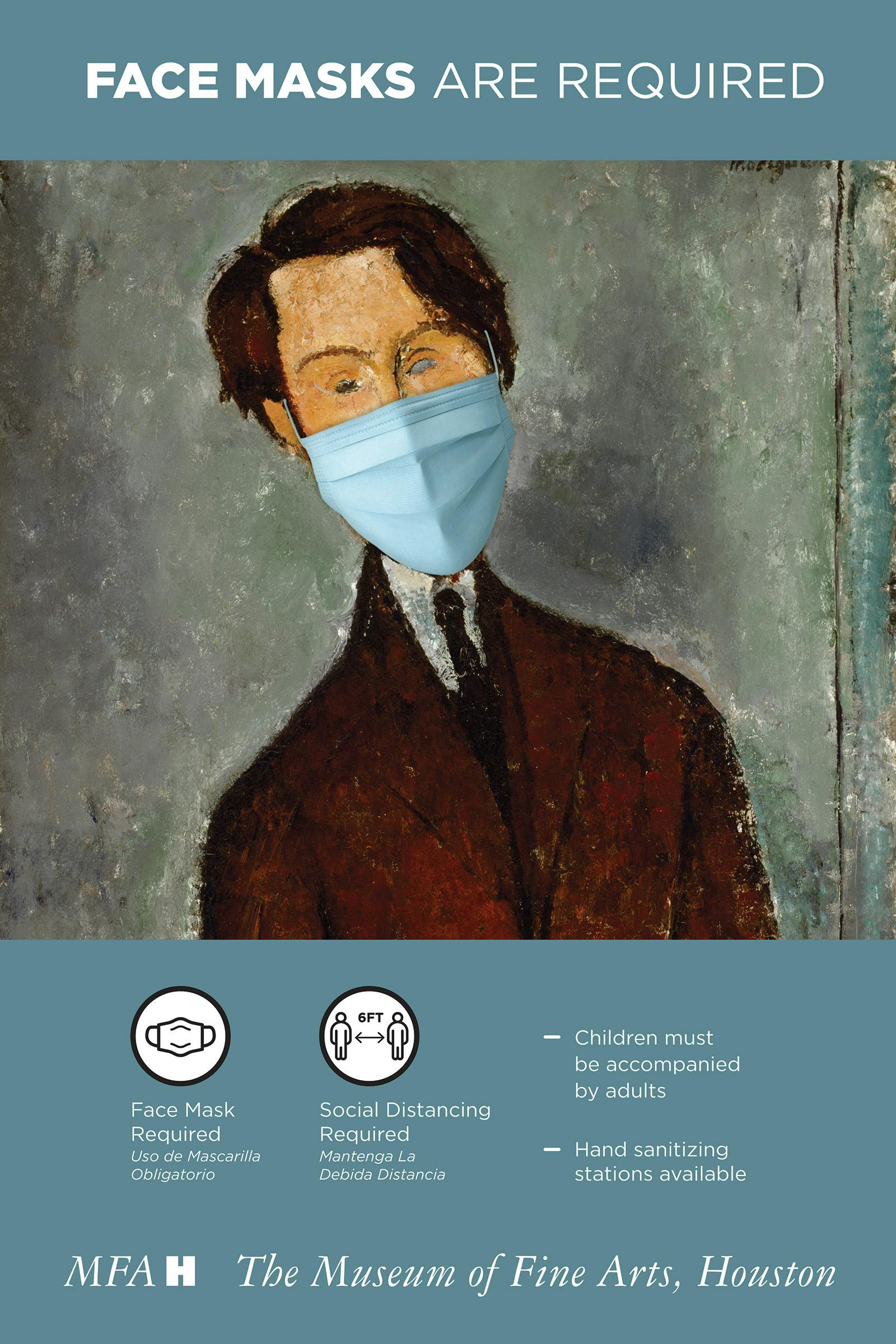

“It’s the same sense of deep uncertainty, a feeling that our lives have been permanently changed in ways we can’t quite understand yet,” he says. Despite the unknowns, on Saturday, the MFAH will become the first major national art museum to reopen to the public since the coronavirus pandemic began. Tinterow and his staff of 660 have prepared a slew of new safety measures, from mandatory masks for all visitors older than age two to temperature checks using thermal-imaging technology. Staff believe that the 300,000-square-foot museum—one of the biggest art museums in the country—is large enough to safely accommodate up to nine hundred visitors, or 25 percent of its capacity. The experience will be “touchless,” meaning that employees will open and close all doors, and they will closely enforce the requisite six feet of distancing.

“I have been eager to reopen when I felt we could do that safely and with the permission of officials,” Tinterow says. “That time has come. I don’t believe we’re creating an attractive nuisance. I think we are providing the safest possible environment for people to step outside of their houses and enjoy works of art.”

CFO Eric Anyah led the museum’s task force on reopening, bringing together members of every public-facing staff area for regular video meetings to go over new protocols and ensure that new supplies like hand sanitizer, masks, and gloves were ordered and stocked. Meanwhile, Tinterow and others at MFAH spoke daily with government officials and colleagues at other museums around the city, country, and world.

MFAH curator Alison de Lima Greene was traveling in New York in late February and early March and so had an early view of the seriousness of the pandemic in the United States, quarantining herself immediately upon returning to Houston. Now, through her contacts with museum colleagues across the globe, she has an optimistic sense of what’s possible for MFAH with strict onsite safety protocols and good public health management in the broader community.

“Our colleagues in Berlin were among the first museums to reopen,” Greene says. “Talking to friends in Hong Kong, where the pandemic was contained through fantastic government and local response, the art world started up there more rapidly than almost anywhere else in the globe. So, we are watching. We are being very careful. The safety of our guests matters to us first and foremost—as well as the safety of our staff. But we also don’t want to be the dog in the manger denying access when we can safely offer it.”

In a time of trauma, anxiety, and partisan-tinged outrage, Tinterow and his staff know that the museum might be accused of either putting lives at undue risk or infringing freedoms with safety protocols. He expresses confidence that cooler heads on both sides will prevail, however, because of what he’s seen from business and institutions that have already reopened.

In particular, a visit last week to the Houston Museum of Natural Science (HMNS), which has been open since May 15, convinced Tinterow that the public was interested in a return to the museum experience and was willing to observe strict safety measures. “People were readily conforming to the same set of protocols,” Tinterow says. “I could see happy visitors entering the museum. I thought, ‘Okay! If they can do it, we can do it.’” At least two other Texas art museums have followed suit, both in San Antonio: the Briscoe Western Art Museum opens tomorrow, and the San Antonio Museum of Art will open May 28.

Tinterow notes that MFAH doesn’t face the same kinds of social distancing challenges that museums like the Louvre might face with crowding around the Mona Lisa. “It’s only when we have a Van Gogh exhibition that we have several people trying to look at the same work of art at the same time,” he says. Even so, he emphasizes the museum’s “state of the art” ventilation and HEPA filtration.

Tinterow also stresses that he expects the financial gain of reopening to be marginal for the museum, because of lower attendance and new costs associated with safety supplies. “We don’t exist to make money,” he says. “We exist to provide opportunities to see works of art. That’s been our guide star as we dealt with closure, the anxiety of the pandemic, and the hard work to make reopening possible.”

By his estimate, the shutdown has already cost the museum about $5 million in revenue, which will be covered by a combination of emergency grants and donations and the museum’s own rainy day fund. (Many museums, of course, do not have such deep pockets.) MFAH has kept all 660 permanent staff members paid in full throughout the pandemic, only letting go of short-term, exhibition-specific contracts. The museum’s campus expansion and renovation, in progress since 2012, is still slated for completion in November.

MFAH had just opened three new exhibits in the weeks before the mid-March shutdown: “Francis Bacon: Late Paintings,” “Glory of Spain: Treasures From the Hispanic Society Museum & Library,” and “Through an African Lens: Sub-Saharan Photography From the Museum’s Collection.” In each case, the museum has been able to keep the show available to viewers, in some cases extending the run. For example, the Bacon exhibition was originally scheduled to close May 25; now it will be on view through August 16, thanks to extended loans from relevant collections.

“One of the things we’ve seen is the camaraderie that exists between many people in this era of crisis, all politics aside,” Greene says. “Every museum has sought ways to support their sister institutions as we have to rethink and re-juggle our schedules.”

The Bacon exhibition is a traveling show originating from the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Houston will be its only American stop. A review of the show from just before the shutdown called it MFAH’s “new blockbuster.” Greene, who organized the showing, thinks audiences will find special relevance these days in the work of the great British painter known for his intensely emotional figures.

“When we look at Bacon’s paintings in the exhibition, we see everything there that makes us human: love, sex, death, and a kind of celebration of the physical,” she says. “I think when we’re all sitting at home so many days of our lives right now, we think about these things. They matter to us.”

Greene also notes the sensory importance of in-person viewing, especially for those craving an in-person experience: “You can call up on your computer images of every painting he ever created, but nothing seen on a flat computer screen conveys the full majesty of standing in front of a great painting.”

After a pause, she adds: “Standing six feet away from everyone else.”