Texas reveres its heroes, but it relishes its bastards. Outlaws, card cheats, bank robbers, barroom brawlers: these are the grist for some of our most beloved stories and nearly all of our country songs. Perhaps it’s no surprise that we get such a kick out of slippery, scheming characters who are driven purely by their own self-interest and who don’t give a damn what anyone else thinks. Our state was founded by mavericks and malcontents. The Texas motto may be “Friendship,” but our ethos was built on Davy Crockett’s parting words to his fellow Tennesseans: “You may all go to hell, and I will go to Texas.”

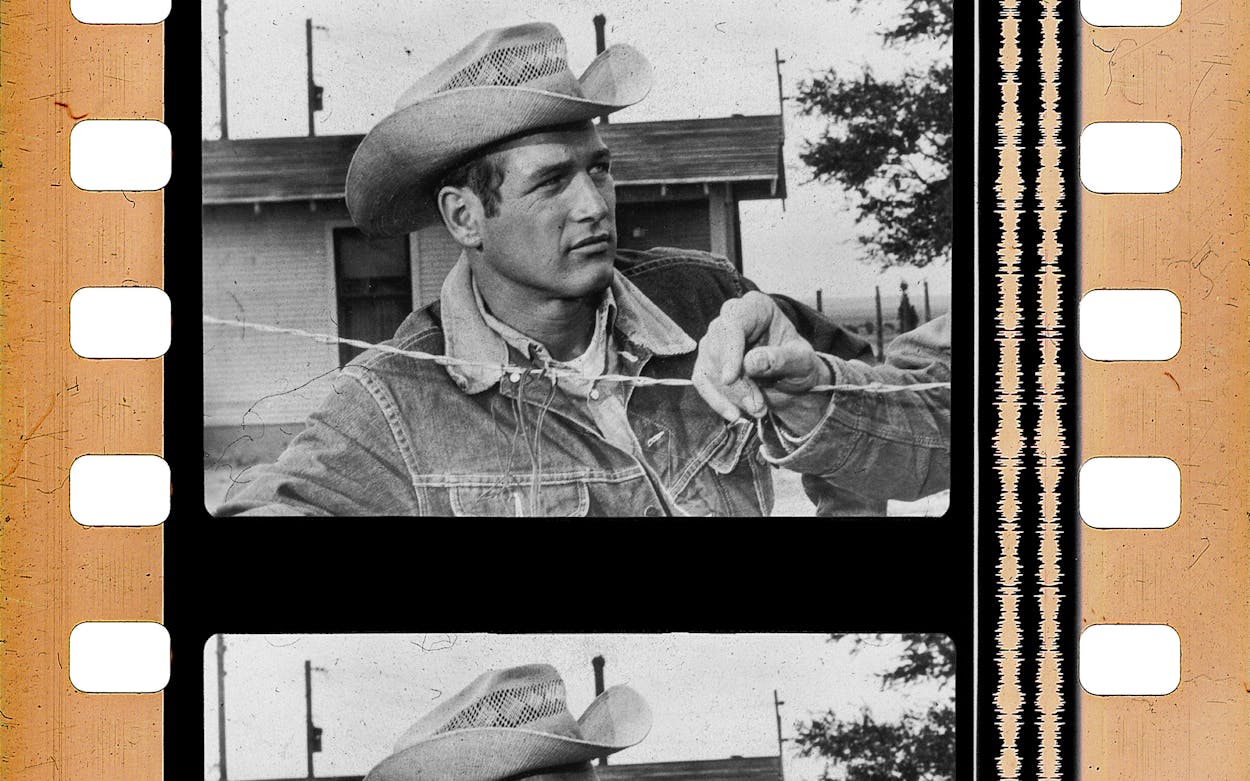

Out of all the great Texas bastards, Hud Bannon may be our most beloved. Certainly he ranks among our most consummate. The title character of Martin Ritt’s 1963 anti-western Hud, played with knife-in-the-ribs sharpness by Paul Newman, is a modern cowboy who ticks all those boxes of moral turpitude. Hud prefers Cadillacs over horses, and booze and married women over just about everything else. He’s charming and capable; when he is on a horse, he sits tall in the saddle, and when he struts into the local saloon, the barflies all cheer his name. Everybody knows Hud. And everybody knows that bastard is not to be trusted.

Hud is derived from Larry McMurtry’s slim debut novel, Horseman, Pass By, a quintessentially Texas story about a hardscrabble family of ranchers living in the Panhandle, on land that is perched along the fault line of a looming generational shift. Hud’s father, Homer (Melvyn Douglas), is a doddering, sanctimonious cattleman whose ethics are firmly stogged in the yellowing Code of the West. Naturally, he and Hud don’t get along. Caught between them is Lonnie (Brandon De Wilde), Homer’s grandson, who admires the old man immensely but whose transistor radio–fueled teenage dreams have him longing to go out and whoop it up with his Uncle Hud.

When an outbreak of hoof-and-mouth disease hits the Bannons’ herd, threatening the family’s entire livelihood, Hud and Homer’s passive-aggressive cold war finally erupts. Hud—that bastard—wants to sell off their tainted cattle quickly, before anyone’s the wiser, then turn the ranch over to the oil companies. Homer would sooner let it all die with him than transgress his morals. In McMurtry’s novel, their schism reflects the rapid changes happening all around Texas in the wake of the oil boom, where the frontier is being parceled off and surrendered to urban development, and ranching as a viable industry is dying a slow death. Hud’s ruthless pursuit of money hastens the end of Homer’s more natural, arguably more edifying way of life.

In the movies, of course, Texas often stands in for America itself: it is the last bastion of American myth, the final proving ground of our rugged pioneer spirit. Ritt, along with screenwriters Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank Jr., saw in McMurtry’s hyper-regional tale the opportunity to tell a broader story about the nation, which had entered an existential crisis in the sleepy wake of World War II—teetering, like Lonnie, between righteousness and rot.

“We sensed a change in American society back then,” Ravetch said in 2003. “We felt that the country was gradually moving into a kind of self-absorption, and indulgence, and greed.” As Ritt told another interviewer in 1983, he wanted to make a film about a man who was “committed to his appetite and only to his appetite.” It was the kind of character that, in most Hollywood movies to date, would have been fully chastened and reformed by the third act. But Hud would earn no redemption. “Why don’t we take that kind of American hero,” Ritt said, “and show that he really is a jerk?”

To their shock, however, the audience didn’t think Hud was a jerk. “The kids loved Hud,” Ritt lamented. “That son of a bitch that I hated, they loved.” The film’s many teenaged fans hung Hud posters in their bedrooms, and they wrote letters to Ritt to tell him how Hud was right. Newman bemoaned in the magazines that his character’s utter repugnance seemed to have slipped right by most of them—that he couldn’t believe that “all they saw was this Western, heroic individual.” Hud, the critic Pauline Kael would declare, wound up as “just possibly the most schizoid movie produced anywhere, anytime”: a film intended to denounce American materialism and selfishness that had only ended up making it all seem so incredibly cool.

To Kael, the root of the problem was that they’d cast Paul Newman, an actor whose charisma superseded any vain attempt to weaponize it. Newman combined Marlon Brando’s brute magnetism with James Dean’s wounded vulnerability, a potent brew that proved irresistible to rock and roll–crazed youngsters who were hungry for rebels, both with and without causes. It didn’t help that Newman was almost supernaturally good-looking either. No matter how callous or cruel his character, it seemed, his sins would all be washed away in the pool of Newman’s big baby-blues.

But then, Hud was always supposed to be handsome. (As Newman would later say, “That’s exactly what made the bastard dangerous.”) What truly undercut the attempt to make him repulsive was Newman’s ability, unique among his contemporaries, to make aloof self-interest seem heroic—the only honest response to all the phonies trying to put one over on the common man. One of the film’s working titles, after all, was Hud Bannon Against the World. What person, especially a young one, can’t empathize with that? When Hud justifies selling off the poisoned cows by decrying all the “price-fixin’, crooked TV shows, income-tax finaglin’, souped-up expense accounts” and the sundry other cheaters gaming the system, the audience’s knee-jerk response isn’t “damn him.” It’s damn right.

That Hud’s creators might have expected otherwise seems at best naive, and at worst disingenuous. They’d taken Hud, a relatively minor character in McMurtry’s novel, and puffed him up into a living legend. Hud got all the movie’s best lines—many of them pilfered from other characters—and they made nearly every other character around him a passive dud. Movie Hud was also much less of a monster. In the book, Hud torments Halmea, the family’s Black housekeeper, before finally raping her in the most brutal passage of McMurtry’s novel. The film transforms her into the white Alma, played with sultry earthiness by Patricia Neal (who won a well-deserved Oscar for her performance), while Hud’s campaign of harassment is similarly softened and Hollywoodized into a teasing, mutually flirtatious dance. After a drunken Hud forces himself on Alma, she even confesses to Hud that “it would have happened eventually without the roughhousing,” given that she was so darn attracted to him. The film goes to great lengths to humanize the supposedly irredeemable Hud, even giving him a sympathetic backstory: here he’s grieving both his mother and his brother, the only people who truly loved him. It all proves so effective that when Lonnie asks his grandfather why he’s always picking on poor Hud, again the audience can’t help but agree.

Homer’s reply to Lonnie is sage, and it’s delivered with a weary grace that helped Melvyn Douglas win his own Oscar: “Little by little,” he says, “the look of the country changes because of the men we admire.”

It’s a great line, and one that’s proved endlessly adaptable to anyone who has ever written about Hud’s canny prescience in predicting [fill in your favorite American megalomaniac]. But these are so clearly not Homer’s words, nor are they McMurtry’s. They’re a sermon handed down from on high by the filmmakers, who would then lay the blame for the film’s “shocking” misinterpretation on the audience’s own moral failings. “If I’d been near as smart as I thought I was, I would have seen that Haight-Ashbury was right around the corner,” Ritt would say. “The kids were very cynical; they were committed to their own appetites.”

Baby-boomer selfishness is certainly one explanation for why “the kids” were so drawn to Hud. Even if it seems hard to square the free-love hippies of Haight-Ashbury with Hud’s money-grubbing, every-man-for-himself philosophy, the leap from the libertine indulgences of the sixties into the “Me” Decade self-gratification of the seventies, and finally to the libertarian excesses of the eighties and beyond are well-documented. But more likely, those cynical kids were simply tired of hearing that kind of preaching from their elders, especially since those same elders seemed to be aching to send them off to die in more foreign wars. Compared to this phony bill of goods, Hud’s lament that “this world is so full of crap that a man’s gonna get into it sooner or later whether he’s careful or not” sounded real. And to the kids, it seemed, the only way out was to wave a dismissive “to hell with it all” and pull down the shade, like Newman does in Hud’s iconic final frames.

I recently went to see Ethan Hawke present a screening of Hud at the Austin Film Society, where Hawke had curated a Newman retrospective as a companion to his recent HBO docuseries, The Last Movie Stars. Hawke introduced Hud as “arguably one of the greatest Texas movies of all time,” and from the crowd’s enthusiastic response he didn’t really need that “arguably,” nor did he need to offer much in the way of justification. In his brief remarks, Hawke commended Ritt’s direction, as well as the Oscar-winning black-and-white cinematography of James Wong Howe, who captured the low plains of North Texas in all their portentous beauty. But the bulk of Hawke’s praise was reserved for Newman. Hawke mentioned that his friend and frequent collaborator, the director Paul Schrader, had even called Newman in Hud ”the single greatest performance by an actor in cinema history.” It was another bold statement, after which much of the audience again clapped in enthusiastic agreement. Some sixty years later, it seems, Texas still loves that son of a bitch.

The abiding local love for Hud is perhaps simpler to explain. Whether you think that Newman’s acting is truly the greatest of all time, you have to admit he sure put a lot into making Hud seem genuine. Newman trained with the dialogue coach Bob Hinkle—who had taught James Dean and Rock Hudson how to talk on Giant—learning to sharpen his R’s and stretch his vowels until they were as broad and flat as the Panhandle. Newman also reportedly spent some time working on an actual Texas ranch in preparation, roping steer and mending fences and properly roughing up his hands. When McMurtry visited the set of Hud in Claude, Texas, an experience the author chronicled with typical ironic remove in 1968’s In a Narrow Grave: Essays on Texas, he noted that Newman had even “picked up the cowboy’s habit of cocking one hip higher than the other” when he stood. Still, perhaps what truly marked Hud Bannon as a Texan was the giant chip on his shoulder.

“Any number of people assured me they knew someone just like Hud,” McMurtry wrote. “Their Hud was a real hellion, they told me—if they were men their tone indicated that he was the sort of man they almost wished they had been: tough, capable, wild, undomesticated.” McMurtry added that most of these men knew they should strive to be more like Homer, who more closely resembled the man their daddies wanted them to be. But they preferred Hud all the same. Deep down, perhaps they also felt that their birthrights were being squandered or stolen—by the government, by suburban sprawl, by time itself. As McMurtry wrote, Hud resonated because he is simply “one of the many people whose capacities no longer fit their situations,” an anguish that has been passed down through every successive generation of Texan.

McMurtry suggested that this loss of purpose makes Hud an inherently tragic figure. Hud is “a gunfighter who lacks both guns and opponents,” he wrote, left to turn his naturally violent impulses inward, directing them toward his family and his community. Still, I don’t think Hud is nearly as trapped nor as self-immolating as McMurtry suggests, nor is he as defeated as Ritt’s film clearly hoped to make him out to be. In the years since the film’s release, in fact, Hud has proved to be a story about a new breed of Texas gunfighter, whose weapons are his words and his wiles. Instead of shooting up the local saloon, the Huds of the world have the stock market and Washington, D.C., in their sights. On the eve of George W. Bush’s presidency, the columnist Peggy Noonan wrote him a mash note remarking that Bush “grew up in a Texas where boys wanted to be Hud,” and I don’t think she meant it as an insult. Hud’s many acolytes grew up and learned to recast his cynicism as canny pragmatism, even patriotism. Today the same scheming self-interest and profit-driven amorality that once made Hud such an outlaw are the bedrocks of the establishment.

But even if you dislike the way the country has changed in his image, it’s pretty difficult not to marvel at Hud’s audacity in spite of yourself. Even the young, presumably white-collar and slightly liberal Austin crowd at my screening of Hud laughed right along with him, far more than they gasped or recoiled. Although we may not want to admit it, Hud is the kind of Texan that we relate to whenever it seems like everything has been stacked against us, when we’re forced to rely upon our wits and our hustle, and bluff our way through another bad hand. The bastard may cheat, but damn it, he wins—and sometimes that’s all we care about.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Movies

- Film

- Larry McMurtry