The Texas Rangers are one of the oldest, most storied law enforcement agencies in the world, so it’s remarkable that there are so few films about them. Not films with Texas Rangers in them: there are scores of those, dating back to the silent era, when early cowboy stars such as Tom Mix and Buck Jones churned out a one-reeler a week playing interchangeable Rangers tasked with rounding up cattle rustlers and Mexican “banditos” before marrying the sweet farm girl back home. But like the nineteenth-century saloon songs and dime-store novels that first celebrated the Rangers’ exploits, those on-screen depictions were more interested in legends than history lessons. In pop culture, at least, the Texas Ranger has proved most durable as an idea—the stoic, square-jawed manifestation of all that is honorable and exceptional about our state.

The facts would only get in the way of that adulation, particularly given that the true story of the Texas Rangers is a messy one, intermittently ugly and inspiring. When the law enforcement agency was founded in 1823, it was a loose coalition of men tasked by Stephen F. Austin with fending off “hostile Indians.” As the Rangers trained their sights first on Mexican soldiers, then eventually on anyone else they deemed to be a threat, Texas’s oldest police force became an all-purpose purveyor of frontier justice, with all the racism, brutality, and extrajudicial murder that implies. In most popular accounts of the Rangers, these excesses have been largely excused, if not ignored.

Across more than a century of movies and TV shows in which the Texas Rangers have played some part, they’ve almost always been presented as heroes—complex, occasionally deeply flawed heroes, perhaps, but heroes nonetheless. In tandem with Texas Monthly’s new podcast, White Hats, which delves into the warts-and-all true history of the Texas Rangers, we’ve rounded up five fictional portrayals that have proved the most influential in shaping that cultural perception. Maybe these depictions don’t tell us who the Texas Rangers really are. But they do tell us plenty about who we want them to be.

The Texas Rangers (1936)

Released in a decade when most westerns were relegated to B-movie filler on double feature bills, Paramount’s The Texas Rangers represented a major investment—not only in the Galveston-born director King Vidor, but in the idea that Texas’s wily frontier force could become modern mythical heroes, on par with Eliot Ness’s Untouchables or the Knights of the Round Table. Vidor’s 1936 film was based on Walter Prescott Webb’s history book cum hagiography, The Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier Defense, and it arrived just as the real-life Texas Rangers were undergoing one of their periodic rebirths. In 1933, most Rangers had found themselves discharged and vindictively scattered to the winds by Governor Miriam “Ma” Ferguson. In their absence, Texas crime had surged, driven in part by the many Depression-era gangsters who’d suddenly found safe haven here. By 1935, the Texas Rangers were back, newly “professionalized” under the aegis of the just-founded Texas Department of Public Safety and raring to clean up the state.

Digging back into the unit’s fabled past to christen its future, Vidor’s The Texas Rangers posited the lawmen as Wild West saviors who were blessed with near-superhuman skill. These were singular men, “molded in the crucible of heroic struggle, guardians of the frontier, makers of the peace,” as the film’s closing narration proclaims. Their heroism ensured the prosperity, sanctity, and very future of Texas—and, by extension, of America itself. That said, The Texas Rangers also didn’t overlook the Rangers’ most titillating appeal: for many of these men, the badge was all that separated their methods from those of the outlaws they pursued.

As a product of Hollywood during the era in which it adopted a strict self-censorship code, The Texas Rangers doesn’t stray too far into that darkness. Fred MacMurray plays Jim Hawkins, a stagecoach robber who schemes to join the Rangers so he can play both sides of the law. But Hawkins is so impressed by the Rangers’ skill and bravery, he’s quickly reformed. By the time he enters a final showdown against his former partner in crime, Hawkins is every bit as virtuous and square as you’d expect from a cowboy played by the dad on My Three Sons. Nevertheless, The Texas Rangers spoke to the secret, subtextual fascination with these white-hat heroes who bore an intriguing touch of moral gray. What could be more Texan? Or American?

See also: Lonesome Dove (1989); PRC’s 22-film Texas Rangers series, beginning with 1942’s The Rangers Take Over; John Wayne in 1961’s The Comancheros; any of the several adaptations of Zane Grey’s novels The Lone Star Ranger and Last of the Duanes.

The Lone Ranger (1949–1957)

If a single work of pop culture can be credited with inflating the Texas Rangers’ already-outsized egos, surely it’s The Lone Ranger. Commissioned by a Detroit radio station owner who wanted to invent a wholesome cowboy hero for kids, the Lone Ranger was, by his very nature, less character than cipher. Here was a Texas Ranger who was so self-sacrificing in his endless pursuit of truth and justice that he had given up his identity entirely, becoming instead a “Masked Man” who sought no recognition and accepted no reward. The Lone Ranger’s adventures spilled across the whole of twentieth-century media, spawning movies, cartoons, and comic books. But it was the eponymous fifties TV show starring Clayton Moore that most directly inspired a generation of impressionable youth to shout “Hi-yo, Silver!” from astride their broomstick horses and to look up to the Texas Rangers as paragons of virtue.

The Lone Ranger may have been partly based on the real-life Texas Ranger John R. Hughes, or perhaps the exploits of U.S. marshal Bass Reeves. But the character’s true origins lie in the set of strict guidelines laid out by his cocreator, Fran Striker, who maintained that the Lone Ranger should fire his guns sparingly, abstain from smoking and drinking, and even use precise grammar, “without slang or dialect.” To avoid offending anyone, the Lone Ranger’s adversaries were also rarely anything other than corrupt white men. This sanitized spin on the Texas Ranger life—along with the Lone Ranger’s chummy partnership with his Native American pal, Tonto—obviously bore little resemblance to the real-life Texas Rangers, who were regarded by most Native Americans and Mexicans as roving, bloodthirsty thugs. It was also a departure from earlier notions of the Rangers as state-sanctioned gunslingers. The Lone Ranger presented an idealized fantasy, one that whitewashed the Texas Rangers into something akin to avenging angels.

See also: Tales of the Texas Rangers, the 1950s, Dragnet-esque anthology series in which Willard Parker and Harry Lauter played squeaky-clean Rangers who tracked bad guys across various eras of Texas history; any of the movies in which Gene Autry or Roy Rogers played a Texas Ranger.

Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

By the sixties, audiences were bored with spit-shined, moralistic lawmen. They increasingly favored westerns that revolved around nihilistic gunslingers, ruthless bounty hunters, and other outlaws. This shift toward cynicism bordering on nihilism reached a tipping point with Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, an instant phenomenon that revived the thirties Texas bank robbers Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker as folk heroes for a decidedly antiheroic age. Penn’s film is clear about its allegiances. Riding shotgun with these charismatic criminals, the viewers are naturally on their side. By default, Bonnie and Clyde makes antagonists out of the real-life lawmen who were hot on their tail—chief among them Texas Ranger Frank Hamer, who’d come out of retirement to lead the charge in cutting down the Barrow Gang.

Hamer was far from spotless himself. In his day, he’d earned a reputation for roughing up suspects and getting into needless gunfights, and, allegedly, he’d even threatened a Texas state representative who dared to investigate his various misdeeds. But Bonnie and Clyde made Hamer out to be something worse than violent or corrupt. Played by Denver Pyle, the film’s version of Frank Hamer is a puffed-up, incompetent buffoon. In his one big scene, which was wholly invented for the movie, Hamer is captured by the Barrow Gang, who force him to pose for humiliating pictures while Warren Beatty’s Clyde, claiming the moral high ground, berates him with, “You oughta be home protecting the rights of poor folk, not out chasing after us!”

Bonnie and Clyde was released in 1967, the same year the Rangers committed civil rights violations while attempting to quash a peaceful protest by migrant agricultural laborers in the Rio Grande Valley. The film’s characterization of Frank Hamer was a fabrication; it left his widow so incensed that she sued Warner Bros. for defamation, eventually settling out of court. (Decades later, Kevin Costner would give Hamer a far more sympathetic portrayal in The Highwaymen.) Yet the sentiment it represented was real, reflecting a growing sense that the Texas Rangers were no longer sacrosanct. They were men to be jeered as much as they were to be revered.

See also: True Grit, both the 1969 and 2010 versions, in which the Texas Ranger known only as LaBouef (played by Glen Campbell and Matt Damon, respectively) is a principled but arrogant blowhard who’s taken down a peg or three by the dissolute antihero Rooster Cogburn; the 2005 Tommy Lee Jones comedy Man of the House—arguably the most mortifying thing ever associated with the Texas Rangers name outside of the last few seasons of baseball.

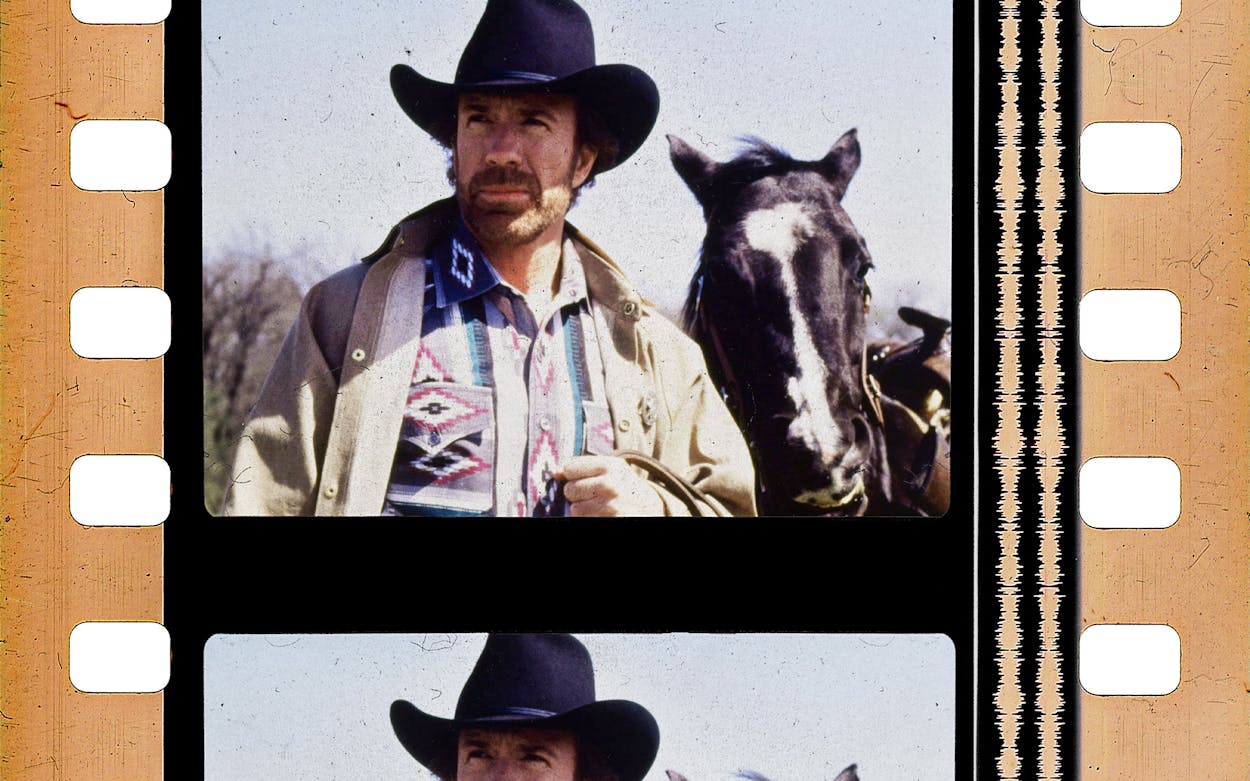

Walker, Texas Ranger (1993–2001)

In 1993, the Texas Rangers were facing yet another existential crisis, this time from Governor Ann Richards’s mandated promotion of several (gasp) women into their traditionally good ol’ boy ranks. “I see the brotherhood slipping,” the venerable Ranger Joaquin Jackson told Texas Monthly that year, bemoaning the quota-filling bureaucrats he believed were ruining his once-elite fighting force. The Rangers had other reasons to worry: their usual by-any-means-necessary tactics of investigation and intimidation were facing growing scrutiny from a new generation of legislators, who were not as predisposed to look the other way. More and more, the Texas Rangers seemed out of step with the modern world.

Striding onto TV screens that spring, CBS’s Walker, Texas Ranger delivered a roundhouse kick to all that. Chuck Norris’s Sergeant Cordell Walker offered a proud, and proudly ludicrous, throwback to the Texas Rangers of lore. Here was a pugnacious one-man army who carried an unshakable moral authority, at a time when the Texas Rangers seemed to be losing their grip on theirs. Norris’s Walker believed firmly in the old cowboy’s Code of the West—a ruggedly individualistic, staunchly conservative worldview that put him in direct confrontation not just with the usual border smugglers or the occasional grizzly bear, but with contemporary social ills such as addiction, cybercrime, and, uh, the AIDS crisis. Walker, Texas Ranger made slight adaptations to its era, reflecting the changing ranks of the department by partnering Walker with a younger Black Ranger, Jimmy Trivette (Clarence Gilyard), and later it even brought in a (gasp) woman Ranger, played by Nia Peeples. But it was always made clear, both to these characters and to the audience, who was really in charge. In the end, the whole Texas justice system always genuflected before Walker’s awesome might.

In the show’s later seasons, after Ann Richards’s reign had given way to the George W. Bush era (with a little help from Chuck Norris himself), Walker, Texas Ranger took on an even greater political symbolism. It began to seem less like some regressive macho fantasy than like a potent symbol of Texas’s burgeoning right-wing reawakening. The metaphor was made literal in 2010 when Bush’s successor, Governor Rick Perry, made Norris an honorary Ranger, thanking both him and the show for helping “elevate our Texas Rangers to truly mythical status”—right when they were most at risk of being brought down to earth.

See also: Lone Wolf McQuade (1983), the Chuck Norris actioner that laid out the prototype for Walker, Texas Ranger; Extreme Prejudice (1987), in which Nick Nolte plays another Texas Ranger supercop—loosely modeled on Joaquin Jackson!—who crosses the Mexican border to hunt down his former best friend turned cartel boss, single-handedly taking on an entire army of mercenaries.

Hell or High Water (2016)

Joaquin Jackson served the Texas Rangers honorably during his nearly thirty-year tenure, ending his run as one of the most decorated officers in department history. But arguably, Jackson’s most lasting contribution was as a symbol. The Dan Winters photo of Jackson that adorned the February 1994 Texas Monthly cover soon found its way onto book covers and posters, and it quickly turned Jackson into an icon—the stoic embodiment of a Texas that is forever fading. Jackson played into that mythmaking with his frequent forays into Hollywood, not only through his own acting turns in films such as The Good Old Boys and series such as Streets of Laredo, but also by serving as a technical consultant to movie stars, showing them how to walk and talk like genuine Texas Rangers—or, at least, the kind that existed in the organization’s endlessly romanticized past.

Yet Jackson’s final—and finest—contribution in this regard was also the one that strayed furthest from those legends. Jackson spent the last year of his life keeping Jeff Bridges in line on the set of the Taylor Sheridan–scripted neo-western Hell or High Water, with Bridges modeling his Texas Ranger Marcus Hamilton on Jackson’s gruff, weary demeanor. In the film, Hamilton is months away from being forced into retirement when he’s given the chance at one last ride: chasing down a pair of brothers, played by Chris Pine and Ben Foster, who are robbing branches of the bank that’s threatening to foreclose on their family ranch. Hamilton tracks the two across the disappearing West Texas frontier, and he gazes out at his suburbanized surroundings with an elegiac sense of his own denouement. The film shows us that Hamilton is a decent man born of a simpler time—albeit one who’s also given to needling his half Mexican, half Native American partner (Gil Birmingham) with creaky racist jokes. But he’s also painfully aware that he’s operating in a world where “good” and “bad” have long since been blurred by the slow creep of a systemic oppression that now passes for the law of the land.

Hell or High Water subverts those pulp western myths of yore, offering a less glamorous, if no less flattering depiction of what makes the Texas Rangers special—along with arguing for their continued relevance. Hamilton is fearless and clever, but most importantly, he is dedicated, in a way that only the autonomy and (let’s face it) arrogance that come with being a Texas Ranger can allow. He works his case with perseverance and deliberate patience, posting up to watch a small-town bank “like a deer feeder” for hours on end, and still pushing for answers even after he’s retired. While the Texas Rangers built their mythos on violence and adventure, Hell or High Water shows us the kind of monotonous work they actually perform. As the film argues, it’s this steadfastness—and not just their self-mythologized importance—that has made the Texas Rangers such an enduring part of a state that’s forever changing around them.

See also: Clint Eastwood as an aging, regret-and-ennui-filled Texas Ranger in 1993’s A Perfect World; the CW’s Walker (2021–), a mournful spin on Walker, Texas Ranger for our anxious age.

- More About:

- Film & TV