This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Country star Charley Pride steers his golf cart alongside a fairway at Brookhaven Country Club in North Dallas, singing to nobody and everybody: “Remember when pocket change was all we had/all those calls from the corner phone booth collect to Mom and Dad./And that old worn-out couch we called our bed/When our cuisine was pork and beans, bologna, and day-old bread.”

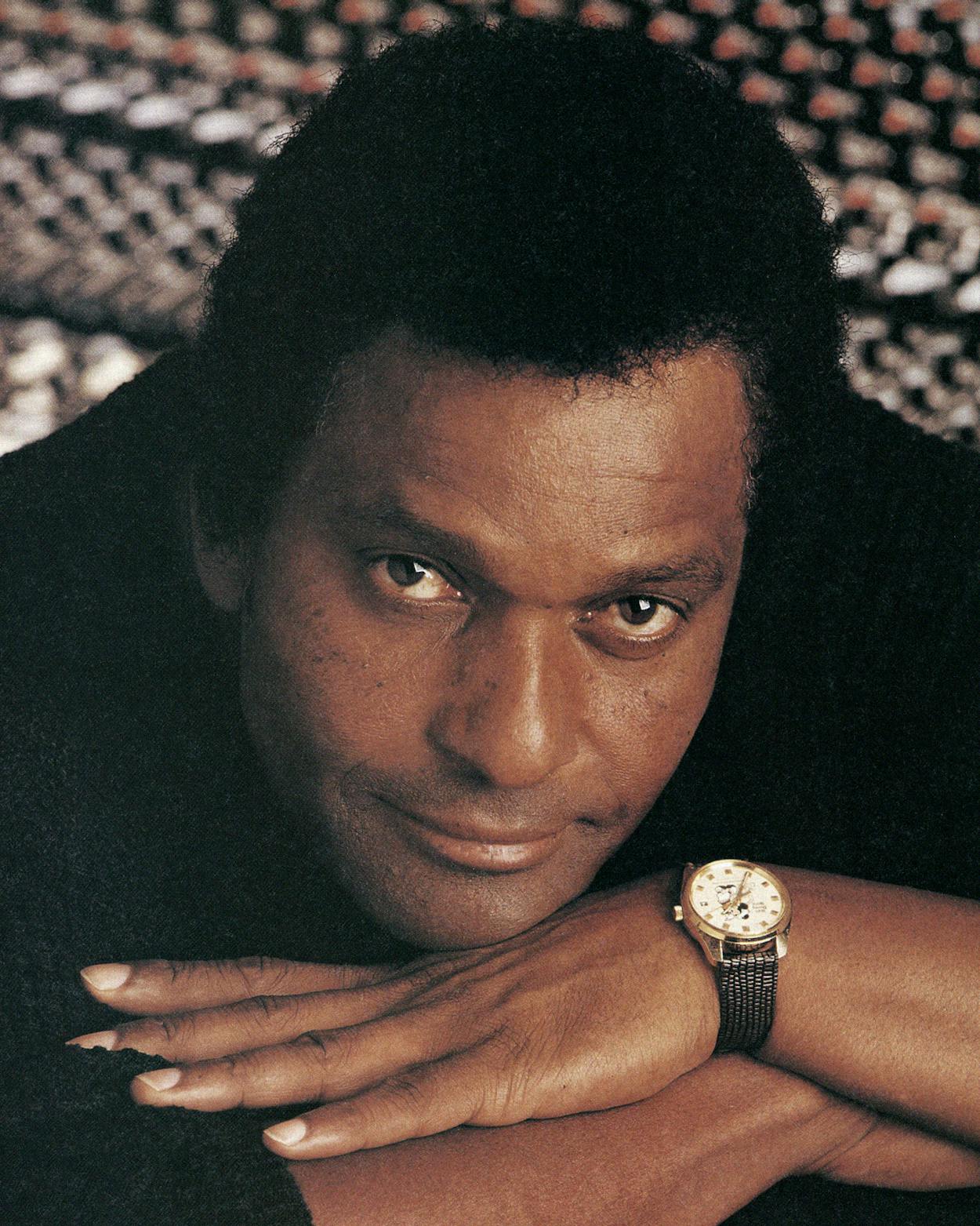

Dressed as usual in Western slacks and a golf shirt, looking as fit as a man about half his 52 years, Charley Pride is in an expansive mood this morning. It helps that there’s a reporter along, because Pride likes an audience offstage as much as on, but the real reason for his fine mood is what you might call the golf-course effect: He’s back on the links after twelve days of touring in Canada, where a snowstorm kept him stuck inside and unable to do the one thing he tries to do every single day, whether he’s at home or on the road. The lyrics to “Nickels and Dimes and Love,” a good new song about the bad old days, are perfect for Pride, because they are both very sentimental and very true—and they also sound especially sweet on the golf course, a location that symbolizes just how far Charley Pride has come.

For a quarter of a century, Pride has borne the dubious reputation of being “the black man who sings white,” of being almost a novelty, even though he has sold 20 million albums and enjoyed a long run of popularity that peaked with his being named the Country Music Association’s Entertainer of the Year in 1971. But there’s more to Charley Pride than music and a mellow baritone voice. During that time he also developed into an astute businessman who controls one of the largest independent banks in the Metroplex, as well as a 247-acre cattle ranch in McKinney. He’s part owner of a truck and van dealership in Albuquerque and has an interest in a New York hotel. He owns the building that houses his enterprises. By choice, he keeps himself outside the country-music loop in Nashville, where he is a respected and well-liked man even if folks do wonder why he seems a bit standoffish.

Today Pride doesn’t crank out the hit records like he used to, but there’s no denying that as country music’s first black star, he had a spectacular chain of successes. “Just Between You and Me” (released by RCA late in 1966, about a year after his first try, “The Snakes Crawl at Night”) marked his entry onto Billboard magazine’s Hot Country Singles chart, peaking at number nine. His last single for RCA, “Love on a Blue Rainy Day,” came just under twenty years later and was his fifty-ninth Hot Country Singles hit. During those two golden decades he amassed an astonishing 29 number one hits.

His music career today is two-pronged. In the U.S., his singles continue to chart modestly—since 1987 he has recorded for 16th avenue Records, a Nashville independent label —and he has matured into what might be called an Old Reliable. Abroad, however, he remains one of america’s biggest singing stars. Over the years he has also become one of the wealthiest men in country music and one of the most independent. Nobody owns a piece of Charley Pride.

When he’s not on the road, Pride begins nearly every day at his two-story, brown-brick office building near his home in North Dallas. He moved to Big D from Montana in 1969 because he wanted to be closer to the country-music action without exposing his kids (two boys and a girl, now ranging in age from 23 to 31) to the racial battles then being fought in Southern cities like Nashville. His domain includes some offices that he leases out, a studio (where he cuts demos), and a pair of suites that house his two production companies, Chardon and Cecca; in addition to handling all aspects of Pride’s career, these two operations publish music and book three other acts.

Those suites are as understated as their owner. Muzak, not country music, fills the air, and the rooms are painted and furnished in muted earth tones. The walls are covered with the usual assortment of celebrity plaques, gold records, photos of Pride with other notables, and press clippings tracking his career. You have to go down a hall toward the private areas to find a mock rest room sign that reads “White” and “Colored,” with arrows pointing in opposite directions—a rare reference to race from a man who has downplayed that part of his life and career. Pride is often referred to as the Jackie Robinson of country music, a somewhat inaccurate analogy because while Robinson opened doors for thousands of blacks who wanted to go into big league baseball, Pride is the only black of real stature in country music. After 25 years, the first and most obvious question remains the one he has had to answer since day one: “How did a black man make it so big in white-dominated country music?”

“I always just say I’m unique,” Pride declares, seemingly resigned that the issue has come up yet again. “This country, this whole world, is race-conscious. And I’ve always tried to not get caught in that syndrome because it causes so many people to lose so much. I believe I am a unique individual not only for being the country singer Charley Pride, who is black, but in all aspects of my thinking. And I don’t say that out of arrogance or ‘bragadoo.’”

This is Charley Pride’s way of saying, “Let’s talk about something else.” He has always been considered a difficult interview, moody and private; and though he says his pet peeve is “not being understood,” he is often contradictory. There is little question that much of his decorum does come from the “uniqueness” of his situation. But Pride is also from the pre-Outlaw generation of country singers, a group that routinely avoids controversy and considers it bad business to offend anyone. Despite this potent double-whammy, he has forged a very successful career. But he doesn’t like to dwell on such matters. He says only half-jokingly that he hopes to wind up like Bob Hope, spending all his time either on the stage or the golf course.

Back at the office, the details of his organization are managed by his wife, Rozene, who married him in 1956. They met in Memphis, where he was playing Negro American League baseball and she was attending college. “My whole thing was I was never gonna marry an athlete or an entertainer,” says Rozene, who wears business suits and speaks in even, considered tones. “I thought they were a bit stuck on themselves—and I got both in one.” As if to prove Rozene’s point, Charley slept through the movie on their first date.

On the surface, at least, Charley and Rozene’s relationship is a classic case of opposites attracting. She casually refers to him as Pride, while he formally calls her Mrs. Pride. He quit smoking a few years back, but she lights up regularly. Though she recollects that they were told they would never be able to hold his career together without experienced, professional management, he remembers them getting nothing but encouragement. He bristles at a report that he’s worth $75 million, saying he has no idea what the true figure is but that he would happily say so if he knew; she curtly allows that she knows exactly what it is but would never reveal the numbers. She notes that while he resists change, she accepts it as inevitable. For Charley, the hardest part of managing himself is making a decision that might hurt someone he likes; for Rozene, hard decisions are unfortunate but bound to happen.

Pride grew up in Sledge, Mississippi, about forty miles south of Memphis, the son of a sharecropper and the fourth of eleven children. His father picked cotton for $6 a day. (In 1975 the sharecropper’s son bought the farm he grew up on.) After dropping out of high school, he played baseball for several Negro American League and minor league teams, continuing to believe that he was a major league prospect long past the age when most hopefuls give up. (He still holds his own at spring training with the Texas Rangers every year.) By 1958 he had faced reality and gone to work at a tin smelter in Helena, Montana, where he played semipro ball for the company team. Two years later, he began singing country, the only music he had ever followed, in local bars. Country touring stars Red Foley and Red Sovine eventually heard him and encouraged him to try Nashville. After one last stab at baseball—a failed 1964 tryout with the New York Mets—he took the singers’ advice.

From the Mets camp in Florida, Pride hopped a bus to Music City. Jack Johnson, an entrepreneur who had been heard to declare that the time was right for a black country singer to make somebody a few million bucks, took one listen to Charley’s on-the-spot interpretations of “Lovesick Blues” and “Heartaches by the Number” and signed him up. Fearful that somebody else would hear Pride and steal him away, Johnson also bought Charley a ticket on the next bus back to Montana.

Johnson and his associate Jack Clement won Pride a deal with RCA. With Clement producing, Pride hit the charts with his third release, “Just Between You and Me.” Once he was somebody, the “uniqueness” business had to be dealt with. In a decision typical of the times, artist, management, and label agreed to play down the race issue. The few love songs Pride cut in his earliest days were chosen carefully, so that nobody would get the wrong idea about a black man singing to white women. In fact, many of his early songs avoided the matter entirely by dealing in country themes like trains, nostalgia, and mom. RCA didn’t even release photos of him until after his warm baritone had established him as a hitmaker. On top of that, Pride rarely sang down-and-out songs, loser’s laments, or boozing ballads. With hits like “All I Have to Offer You (Is Me),” he presented himself as a down-to-earth but upstanding man.

In short, his image was both positive and nonthreatening, and it worked largely because it was more than just image; when Pride first went on the road, he put the audience at ease with his easygoing stage demeanor and jokes about having a permanent tan. Even so, there were a few dodgy moments. Willie Nelson has often told the story of introducing Pride in Louisiana and neutralizing the crowd’s shocked reaction by kissing him on the mouth, as if to bestow a personal seal of approval. (Charley, who is clearly embarrassed by the tale and just as clearly grateful to Nelson for moral support in those tense days, claims the incident actually happened as the two men were getting off a tour bus at a Texas motel.)

By 1971 such tunes as “I’m Just Me,” “Is Anybody Goin’ to San Antone,” and “Kiss an Angel Good Mornin’ ” had made Pride the top draw in the business. It was a time of transition and growth in his career, and so, after eleven years and two management contracts, Pride and Johnson parted ways. Though they had little experience, Charley and Rozene took over the bookings and finances themselves. They are still in charge, although these days Pride makes decisions only after he has heard out the Big Four, a team whose members also include Rozene’s sister, Hortense Ransom, and Pride’s attorney, Jerry Lastelick. Several people who were around Pride in the sixties are surprised to hear of his business acumen, noting that he showed no such interest, let alone skill, in the old days. As for Pride, he says simply, “I didn’t know anything about picking cotton when I started either, but I got to be a pretty good cotton picker.”

Still, there have been times when an MBA might have helped. His setbacks have included a barbecue-grill company that went belly-up despite a distribution deal with Sears, a Charley Pride sausage venture, four failed radio stations, and a couple of private planes that siphoned off too many funds. But those failures are dwarfed by the success of the First Texas Bank in Dallas, of which Pride has been majority stockholder since bailing it out of financial difficulties in 1977. Today it is the tenth-largest minority-owned business in Dallas and the seventh-largest black-owned bank in America.

Even though his status as a hit recording artist is fading—he hasn’t reached number one since 1983’s “Night Games”—Pride’s popularity overseas shows just how carefully he has taken care of business. There is a steady diet of USO tours and a six-week jaunt through either Europe or Australia and New Zealand every other spring. Though a precise breakdown is unavailable, record sales have always been high in countries like Canada and Australia. His “You’re My Jamaica” (1979) was the first number one country record ever cut in England.

Such smooth moves enable Pride to gracefully hold his own despite fickle fans and changing trends. Other stars have meteoric careers, turning into has-beens at forty or parodies of their former selves, but Pride has defined his own arena so carefully that he can remain at the center of its stage as long as he wants. Then he can go play some golf.

John Morthland is a freelance writer who lives in Austin.

- More About:

- Music

- TM Classics

- Golf

- Country Music

- Dallas