This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Art is in the eye of the beholder. Behold, if you will, the black velvet painting. Some consider black velvet paintings art. Others consider them eyesores, or at least clichés of bad taste. Taste aside, black velvet paintings, produced and sold throughout the world, are one of the twentieth century’s most commercially successful art forms.

Most of the paintings we see for sale in Texas and the Southwest come from Mexico, specifically Ciudad Juárez, the capital of black velvet. Mexico has never been much of a market, so most of the black velvet paintings end up in the United States. There is only one well-known American working in the genre—Julian Schnabel in New York—and he is a recent convert.

The black velvet buyer is likely to be anybody: a parent indulging an insistent child with a portrait of ET or Garfield, a pimple-faced gas jockey buying a no-holds-barred portrait of the woman of his fantasies to hang in his first apartment, or a teenage girl who wants more than just a poster of Michael Jackson. The all-time favorite subject of black velvet artists is Elvis Presley. But any image the human mind can conceive of is likely to end up on black velvet: the Mona Lisa, the Pink Panther on a toilet, a pickaninny and a watermelon, even you—if you have a snapshot and about $20.

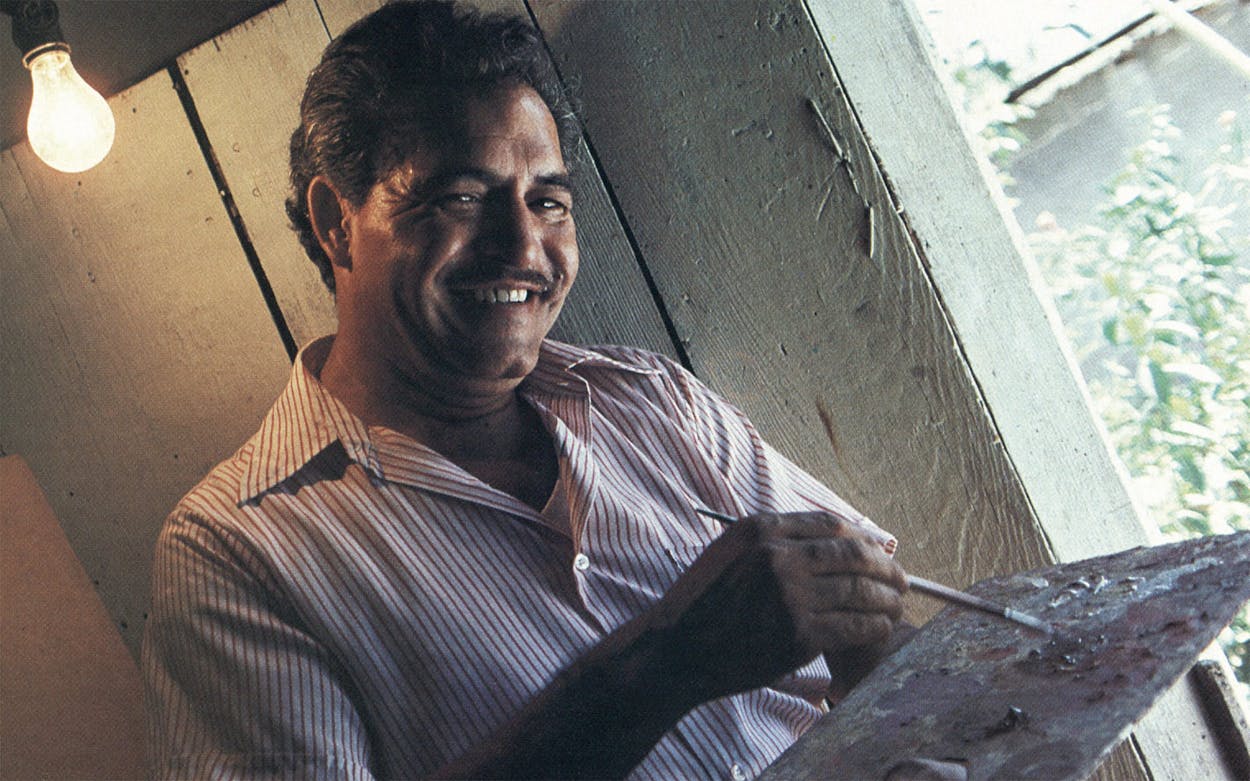

The artists who create terciopelos negros are mostly self-taught, and their paintings are the products of native talent and dogged application. One of the masters of the genre is Sabino Castillo, who lives in Monterrey. If Juárez is the capital of black velvet painting, Monterrey is its spiritual home, the place where, according to the locals, it originated.

Castillo works in the dusty Mercado Constitucion, in a stall made of chicken wire and two-by-fours. Although he picks up whatever custom work he can, Castillo mainly paints for wholesaler José Duque in nearby stall 85. Duque furnishes the paint and the stretched velvet and pays Castillo about $1.75 for each finished painting. The artist used to paint up to forty a day for another wholesaler, but now he does fifteen a day at the most for Duque. He paints seven days a week, nine or ten hours a day. Castillo, who is in his mid-thirties, has been painting for nearly twenty years.

“I like to paint everything—landscapes, animals, portraits. I like to do portraits of Christ. I’m happy to paint one a day of Christ,” he says. Castillo takes a lot of time on each of his paintings. He spent nine or ten hours over three or four days on a portrait of Matt Martinez, Sr., owner of Matt’s El Rancho in Austin, working only from a faded newspaper photo. Complete with handmade frame, the painting cost $30.

Castillo paints each picture—custom or commercial—from start to finish, and he works by himself, turning in his stock of finished paintings to Duque once or twice a week. All black velvet painters work that way. There are no grand factories or assembly lines in the land of terciopelo negro, nor are there any paint-by-number schemes. Each artist develops a formula for his commercial works. Though all of Castillo’s psychedelic waterfalls look pretty much the same at first glance, they are different. Like it or not, each black velvet painting you see is handmade, one-of-a-kind art, something a poster is not, be it a cheap glossy of Michael Jackson or a $250 Amado Peña print.

The average black velvet seller is an itinerant who follows a yearly circuit, hitting one city after another, a street corner here, a flea market there, and moving on when the patrons play out. Chances are his paintings come from a Ciudad Juárez wholesaler known as Juárez Export, which is located in an unassuming one-story turn-of-the-century colonial-style house that has been converted into an office and warehouse. The building is pale pink with rust-red trim; “Juárez Export, Oil Velvet Paintings” and a palette with brushes are painted on the upper right corner of the front. It’s deceptively simple.

Inside, though, is sensory overload. Black velvet is everywhere: Boy George, the Virgin Mary, unicorns, landscapes, seascapes, conquistadores, fruit, flowers, psychedelic mallards, Dobermans, and the office’s centerpiece, Ronald Reagan, backed by a waving Old Glory.

Fernando Nájera and Octavio Fierro are co-owners of Juárez Export. Barely over thirty years old and longtime friends, both are business school graduates, Octavio from the University of Guadalajara and Fernando from Juárez University. Juárez Export, Fernando said, sells between 12,000 and 15,000 paintings a month to 150 distributors, who sell them as far away as England, New Zealand, Lebanon, Israel, and Switzerland, as well as in their primary markets in Canada and the U.S. He said that the firm’s top American markets are in Florida, Missouri, the Carolinas, Indiana, and Texas. In Texas the paintings sell best in Austin, San Antonio, and Dallas. For some reason the market in Houston is poor.

“We employ one hundred one full-time artists now, plus about two dozen more part-timers,” Fernando said. “Also, twenty-five framemakers and ten who make stretchers. Only three of our artists are women.”

In one form or another, Juárez Export has been around for about thirteen years. Originally, a group of established Juárez artists formed a collective with several framemakers and stretchermakers to save money by purchasing raw materials in bulk from the big velvet mills and the paint companies in Mexico City. After several years the artisans realized that they weren’t businessmen, and they decided to find someone to take over the business. And so Juárez Export was born; Octavio came first, Fernando a year later. The company soon expanded from procuring materials to exporting paintings.

“My U.S. customers tell me their business is better than ever before,” Fernando said. “We’re going to have to build a new warehouse this year. This setup is too small now, and the parking is bad. During our busy months there may be four or five semis parked out front at one time. They block traffic, and that annoys our neighbors.”

“Semis?” I asked.

“Yes,” Fernando answered, smiling. “Our biggest customers buy one truckload a month. A semi will hold approximately five thousand of the three sizes of paintings we sell. Most customers take an even mix of sizes.”

Art on that scale requires organization. Octavio, Fernando, and some of their employees just finished taking a course on how to use the office’s new computer. The company’s first computerized subject catalog and roster of artists was hot off the Epson printer. More than two hundred subjects were listed in the catálogo de pinturas, and each reporte individual de pintor listed the artist’s personal data and subjects painted.

Scanning the catalog, I saw cowboys and Indians, Jesus on the cross and the devil on the john, koalas and Pitufos (Smurfs), Bob Marley, Jimi Hendrix, and chicas desnudas (“nude girls”) of all shades. Elvis was there (with tears or with flowers), alongside Bruce Lee and John Wayne. But where were the bullfighters and the campesinos sleeping under cacti and the burros and the pretty peasant girls in native costumes?

“We sell very few paintings of traditional Mexican subjects,” Fernando said. “I must add bullfighters and Spanish dancers to the list. We still produce them. I just made this list up yesterday and must have forgotten them.”

Elvis, of course, is the biggest seller. “We have sold at least twenty-five thousand paintings of Elvis all over Canada, the U.S., and Mexico.” John Wayne is a steady best-seller, as is Bruce Lee. Unicorns and religious themes in general are also evergreens. Lately, Hank Williams, Jr., has been hot, as well as Porter Wagoner and Waylon Jennings. “Dolly Parton flopped, though,” Fernando said with a sigh. Michael Jackson was big during the spring and summer of 1984, but no more. Everywhere I went in Juárez Michael was staring down at me—Michael petulant, Michael jubilant, Michael every which way in between (except desnudo). I gave up after counting 25 different poses. According to Fernando, that many Michaels in stock could only mean that the market was glutted. For what it’s worth, I saw only one Mr. T the whole trip. I could barely resist taking him home, but I was saving myself for either Mel Tillis or Porfirio Díaz, whoever came first. I found neither, but I did see paintings of a kitten listening to a Sony Walkman and a nearsighted turtle mating with an army helmet.

“We get ideas from our artists and customers,” Fernando said. “They will send in magazine photos or cards and say ‘Copy this.’ Sometimes Octavio and I pick the subject. I have ordered some Christmas cards for the artists to copy, and I’ve clipped photos of various stars.”

On a tour of the warehouse out back Fernando showed me where several thousand paintings were stacked, dozens deep, dozens tall, grouped roughly by subject matter. Religious paintings and naked girls were kept on opposite walls.

“A lot of paintings,” I commented.

Fernando turned to me with a look of regret. “I wish you could be here in the summer to see the place. You can barely walk around in here. That’s our busy season. They don’t stay here for long; they’re shipped out almost as soon as they’re finished.”

The artists stretch the velvet themselves and provide their own easels and working places. Everything else—velvet, stretchers, oil paints, and brushes—is supplied by Juárez Export. Fernando emphasized that the artists use only the highest-quality materials. “These paintings,” he insisted, “will last forever.”

I decided that I could not avoid the question any longer. Sure it’s a great business, I asked, but is it art?

Fernando paused. I had touched a nerve. “Sometimes it hurts my feelings that some people think the paintings are a joke,” he said. “Many of the artists really do express their feelings in their paintings. Sometimes even my customers say, ‘Oh, your prices are too high. Why aren’t they lower?’ I tell them, ‘You’re not paying for a machine-made thing. You’re buying something handmade and unique! It’s more special to have a painting of Michael Jackson or the Virgen de Guadalupe than just a cheap poster.’ ”

When I returned to Monterrey, I began my search for the originator of black velvet painting. I was not optimistic about finding him and assumed that such a person would be long dead and that his life would be shrouded in legend and mystery in any case. But, back at the mercado, I was in for a happy surprise. “The originator?” answered José Duque. “Let me think. He painted under the name ‘Dante.’ Yes, he’s still alive. I think he still works at the shop Curiosidades de Monterrey, on Calle Reforma.”

I could barely contain my excitement. It was like finding the inventor of the margarita or the nacho. People in the States had told me of seeing black velvet paintings in Mexico City as early as the late forties, but the identities of the genre’s pioneers had faded with time. So I settled on Dante because I figured he was as close as I was going to get. At Curiosidades de Monterrey I was told that Dante had indeed invented the black velvet painting. He had retired from the shop a year ago and he still lived on the north side of town, but nobody could recall exactly where—somewhere near the corner of Central and California, across the street from a tortillería. He didn’t have a phone. With a healthy dollop of divine providence and neighborly directions (there was no tortillería), I found the house, 207 California. A young man was out front. “Momentito,” he requested, disappearing into the house to fetch his father. After a few moments an ordinary-looking middle-aged man, dressed in neat but worn work clothes, came out.

“Are you Señor Dante, the painter?”

“Sí, señor.”

I had my man.

Given his reputation as the creator of a genre, 47-year-old Jaime Dante Cortés A. lived in extraordinarily modest circumstances. “I am not a rich man, señor. I have a humble house in a humble neighborhood,” he explained as he escorted me into his kitchen–dining room. The house did not look like the home of an artist. One small, unframed black velvet landscape with muted greens and golds hung on a kitchen wall. In that house Dante and his wife had raised six children (three boys and three girls), every one of whom had graduated from or was then enrolled in college. That was where most of the money from his 25,000-plus black velvet paintings had gone.

“Twenty-five thousand?” I asked.

“Yes, at least,” he answered. “Twenty-five a day in my prime, all by myself. I was the first to begin painting on terciopelo, but it was entirely by accident.”

The year was 1955. Dante was eighteen. After several years of apprenticeship and practice with noted Monterrey commercial artist Benito Salinas, Dante had just struck out on his own. He had already sold his first painting, a campesino with a burro, on traditional white canvas, to Herbert C. Chase of West Dennis, Massachusetts. Mostly he painted clothes—shirts, blouses, skirts, leather jackets, and vests—to order. Burros, bullfighters, señoritas, whatever the gringo tourists wanted.

One day that year, Padre Carlos Alvarez of Monterrey’s famous orphanage La Ciudad de los Niños came to Dante’s stall. A mariachi and traditional dance group from the orphanage was to tour the United States, and Alvarez had a black velvet skirt that needed painting. “He wanted the Virgen de Guadalupe,” Dante remembered, the image of the Virgin that had first appeared on a tattered blanket. “As I painted on the black velvet, I became excited by its possibilities. It was something different, and I enjoyed the new shadowing and lighting effects. The cloth took colors without preparation, it was easy to paint on, and the velvet was cheap. That made art accessible to the masses. Anyone could afford handmade paintings because they could be done for so little cost. And people liked the way they looked.

“I painted traditional subjects at first, just as I had on the clothes. Yes, I painted many bullfighters. I went to the corridas and took many, many photos of bulls and matadors to study their form. But I have painted everything—landscapes, seascapes, portraits, everything! My paintings have gone all over the world—United States, Canada, France, Spain, even Russia.” Dante paused and leaned back from the table, quiet again.

After 25 years of working exclusively for Curiosidades de Monterrey, Dante retired last year. “I haven’t painted in two months, actually. I have been designing gardens instead. I will start painting again soon, but only for my pleasure and that of my friends.”

What happened to the skirt? “Oh, it was sold to someone. At the end of each tour the orphanage auctioned off the costumes for additional funds.”

We sat at Dante’s table, sipping Cokes and talking about the black velvet business until sunset, time for me to take a cab home to the far west side of Monterrey.

“No, no, I will not hear of it,” Dante protested. “I will take you there; it is no inconvenience. I’ll borrow my son’s truck.” As he opened the passenger door for me (the outside handle was missing), he apologized for the ugliness and grime. The back of the battered 1964 Dodge pickup was full of gardening tools.

We chugged determinedly through Monterrey’s madcap rush hour, and Dante continued talking. “There are only four or five artists in Monterrey today. Used to be twenty-five or thirty—true artists I mean. There are many more who merely paint by number, so to speak. But Juárez is the capital of terciopelo now.

“I have worked hard all my life, first as a bracero picking cotton in Texas at Rio Hondo, then as a painter. I am proud that black velvet paintings have become so popular. I am not a wealthy man. I live in a poor home. I have no phone or car. But all those velvet paintings sent my children to college, and for that I am very grateful and happy.”

Richard Zelade is a writer who lives in Austin.

- More About:

- Art

- TM Classics

- Mexico

- Longreads