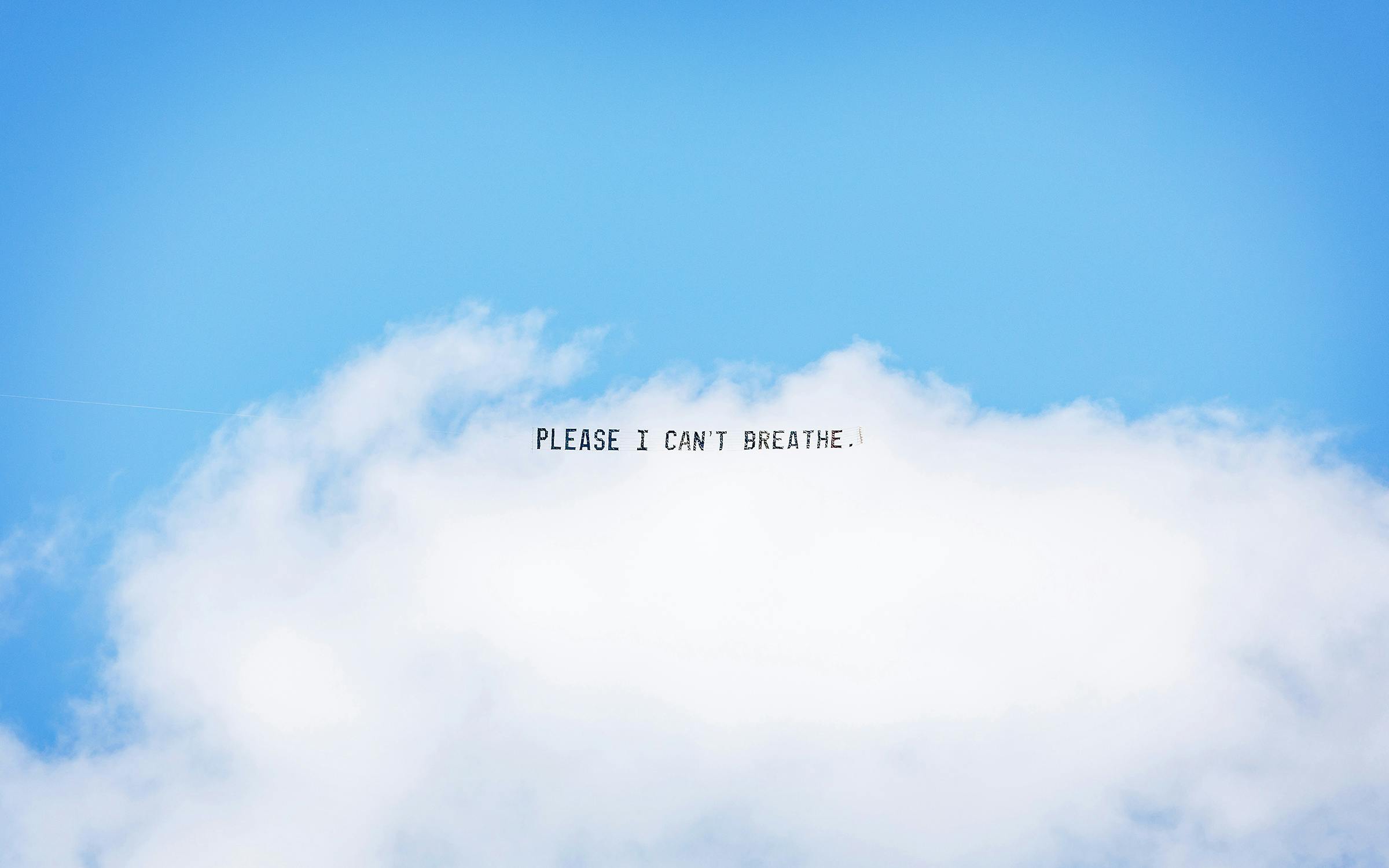

On May 30, a small plane flew over downtown Dallas, trailed by a banner bearing the words “My Neck Hurts.” These were some of the last words spoken by George Floyd, a Houston man who had been killed five days earlier and pleaded for his life as a Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck. More of Floyd’s final words flew overhead in cities around the nation: “They’re Going to Kill Me” in New York City, “Please I Can’t Breathe” in Detroit, “My Stomach Hurts” in Miami, and “Everything Hurts” in Los Angeles. It is striking to see Floyd’s last words framed against empty blue sky. Flown across city skylines, his pleas seem to ask onlookers another question: “Will this make you pay attention now?”

Jammie Holmes, a Louisiana-born visual artist now based in Dallas, conceptualized this grim demonstration. Like many of us, Holmes learned of Floyd’s death through social media; he recalls bracing himself to watch the last few minutes of Floyd’s life in a now viral video. “I was really disgusted and disappointed, and it was just a reminder that we are still dealing with this kind of shit in 2020,” Holmes says. “After watching the video, I put myself in his shoes, and knew that this could have happened to me, or to someone close to me and my family. And I feel disgusted that we as a society haven’t learned anything yet.”

Holmes’s artwork often draws heavily on his childhood in Louisiana and his experiences as a Black man in the United States. In the piece Endurance, Holmes cuts his brother’s hair in front of a blue floral background. “I put flowers behind us because I wanted to tone down the black in us,” Holmes told the New York Times. “I’m 6-foot-3, bearded with tattoos, and I love jewelry. I wanted us to look safer.” Racism and police brutality are unfortunate and familiar topics for him. “I knew I needed to do more than paint another image of this, and that’s when I thought about taking my form of protest to the skies,” Holmes says of his most recent project. So he reached out to Library Street Collective, a Detroit-based gallery that represents him, to fund the project; Holmes then flew banners in cities around the United States as a public art project as well as a national display of solidarity with protests already under way in Minneapolis and beyond.

In June, Dallas Contemporary launched a digital exhibition of Holmes’s banner protests titled “EVERYTHING HURTS.” The exhibition includes documentation of the banners that flew on May 30, as well as links for petitions and memorial funds. To accompany the exhibition, Dallas Contemporary is also hosting a conversation series for the exhibition that started on July 8, with a panel called “Looking Forward: Art + Change in Dallas.”

Texas Monthly interviewed Holmes over email about his artwork, living in Dallas, and why this moment is different than any other time in history.

Texas Monthly: When did you begin teaching yourself art, and how would you say your art has changed over time?

Jammie Holmes: I started creating when I was a kid. When I was young, I didn’t have any other option or way to express emotion. For me, creating was a way to express emotion and gratitude. Giving my mom a gift of something I made was an accessible way for me to show appreciation towards her. Before I started painting seriously, I used to write a lot of my feelings down as notes in my cellphone. When I moved those feelings into painting, my early work reflected a lot of that emotion; I took on a more expressionist route with colors and gestures. From there I discovered that what I really wanted to communicate—after I got those initial emotions out—was my story. I wanted to show people who I was and where I came from and that’s how I moved into more figurative work.

TM: What are elements and methods of creating art that you’re still experimenting with?

JH: I’m really working right now to just hone my skills as a painter. One new challenge for me was a mural I did in the Belt Alley in Detroit, which is a little over twenty-six feet long. This is my first mural, so that was cool to experience and different for my practice. It was a good way to represent the universal language of youth and play. The mural features a young Black boy doing backflips on a mattress, and it was great to see kids identify with the figure as they came through this very public and accessible space.

TM: Location seems to be an integral part of your work. How does being in Dallas now shape and inform your art?

JH: Living for a year in Deep Ellum, I had a very specific moment in which Dallas influenced my practice. I had my first studio in that neighborhood and one day when I was looking out the window of my studio, I noticed that the roof had rusted on the building across the street. I thought that was a nice detail within the city’s landscape and I was inspired to find and paint more of these kinds of details within my painting’s narratives. However, I don’t paint many stories of my time living in Dallas. I really try to focus on telling stories from my childhood in Louisiana, since they might not be told otherwise.

TM: In your video accompanying your digital exhibition, you say that this moment is no longer about white or Black, but about whether people are for racism or unity. What made you say that?

JH: I said that because when it comes down to racism there is so much hatred and division out there, and because now more than ever it seems like people from many different groups are participating in the movement. White, Asian, Latinx, all these people are coming together and it’s about unity for the movement now more than anything. Black people have been fighting for this shit for so long and now my white friends and colleagues, they are teaming up with us and we are all starting to check people on racism. I find there is no middle ground and we can’t preach to be divided; we have to be united on this front if we want to see change.

TM: Does this moment of protests sparked by the killing of George Floyd feel different from other protests against police brutality?

JH: Yes. I think it has a lot to do with Donald Trump preaching so much hate. More people than ever are united in the fact that we can’t have hatred like he displays continue, not in 2020. He has been preaching racist remarks these past three years and is always trying to divide the country. I think the people are really fighting for the movement now because they want to fight back on the hatred that is coming from this country’s leader.

TM: In your “Growing up in darkness” series, you asked the question, “What if I was white?” What inspired this?

JH: This was a question I had to ask myself so many times in my life, especially when I was a kid. Even when I was growing up, I would notice the difference between the way I was treated as a Black child, and the way White kids were treated at my school. I would ask myself what my education would look like, or my community would look like, or what my role in society would look like, if I had been born White. Kids from my neighborhood didn’t have opportunities, and then I realized that that lack of opportunity follows so many Black kids in America. Look at the killing of Tamir Rice, or Trayvon Martin. How would that play out differently had they been White? I witnessed discrepancies in school all the time, saw the differences in treatments and punishments between Black and White kids misbehaving. That’s why I’m so fed up and disgusted, people are still getting away with the same shit.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

- More About:

- Art

- Black Lives Matter

- George Floyd

- Dallas