James Rodney Richard allowed the applause to wash over him that night in New Orleans four years ago. He bowed his head a time or two as if attempting to wrap his mind around such an outpouring of love.

He may have wanted it to stop so he could get on with the prepared remarks he was nervous about giving. Or he may have wanted the ovation to last forever. He was back in his home state for the occasion, one of eight recipients of the Sam Lacy Pioneer Award at the National Association of Black Journalists convention. Richard often used such speaking engagements to admit that he took a long time figuring out the second chapter of his complicated life. In the end, he believed that journey gave his words power.

“Tomorrow is not promised to you,” Richard told the audience. “Some days are good. Some days are bad. You keep on going. Everything is up to you.”

On this one night, there was no talk of what might have been. Or the tragedy that defined so much of his life. There’s no way to know if this was the moment J.R. Richard achieved some kind of peace with how it had all played out. All we know is that in his final years, he became more gracious, more accommodating, and certainly funnier. He was willing to accept the praise showered upon him by so many. Perhaps most of all, he saw larger lessons.

Richard died at 71 last week of complications related to COVID-19, the end of a life defined by the highest highs and lowest lows. In the prime of his ten-year MLB career, from opening day in 1975 until he collapsed from a career-ending stroke in 1980, the Houston Astros right-hander was the most feared pitcher in baseball.

“If I’d have kept on going,” he told the New York Times in 2015, “I’d have rewritten the history books.” Indeed, he might have. At six-foot-eight and 230 pounds, he was intimidating in all sorts of ways. Those who faced him swear his fastball topped 100 mph, even though few radar guns existed at the time.

“If they took the radar gun that they’re using right now and they put it on J.R., when the ball left his hand like that, it was probably going 110,” retired outfielder Gary Matthews, who faced Richard more than any other hitter, told the Times last week. “J.R. Richard doesn’t have to take a back seat to any pitcher that’s ever pitched in the major leagues.”

Richard tormented batters with an even more impressive pitch: a hard slider—very hard, think 91–92 mph—that dipped so violently it seemed to vaporize at home plate. His lack of control made him even better. Or at least scarier for hitters trying to hang in the batter’s box without getting beaned. Over his final six seasons, Richard led the National League in total walks, strikeouts, and batting average against.

His career arc was straight up from the moment the Astros made him the second overall pick of the 1969 draft and gave him his first major league start two years later. He’d grown up in Ruston, Louisiana, and told reporters he developed arm strength by throwing rocks at rabbits and birds. Richard’s reputation really began to take shape in Houston’s minor-league system. A young catcher named Bruce Bochy, who later won three World Series championships as manager of the San Francisco Giants, suffered a broken toe when Richard plunked him with a fastball during batting practice. It wasn’t even Bochy’s turn to hit yet, but teammate Enos Cabell, who’d go on to play first and third base for the Astros, told Bochy to take his place.

“Enos took one look at how J.R. was throwing and told me to get in there,” Bochy told me. “One pitch, broken toe.”

Asked about that story, Cabell said: “Yeah, that’s how it went. I wasn’t getting in there against him.”

Current Astros manager Dusty Baker, then a member of the Los Angeles Dodgers, laughed about the day Richard was scheduled to pitch his team. That day, both the first- and second-string catcher showed up claiming they were injured and unable to play. “An incurable disease when you’re afraid of J.R.,” Baker said. “We had a team meeting and said, ‘Somebody’s going to catch.’ There were a lot of guys who would take days off when J.R. was pitching.”

Oh, about that first major league start. Richard was 21 years old when he struck out fifteen San Francisco Giants in his major league debut. He got Willie Mays three times. Mays had heard all about Richard as the pitcher made his way through the minor leagues. Former Astro Scipio Spinks said when Mays met Richard, Mays said: “Young man, just don’t hit me.”

Richard battled his control issues for four years, then in 1975, he broke through with 203 innings and 176 strikeouts. He led the National League in walks and wild pitches that year. Richard pitched angry because he was angry. He had a chip on his shoulder that seemed to drive him. He trusted few people.

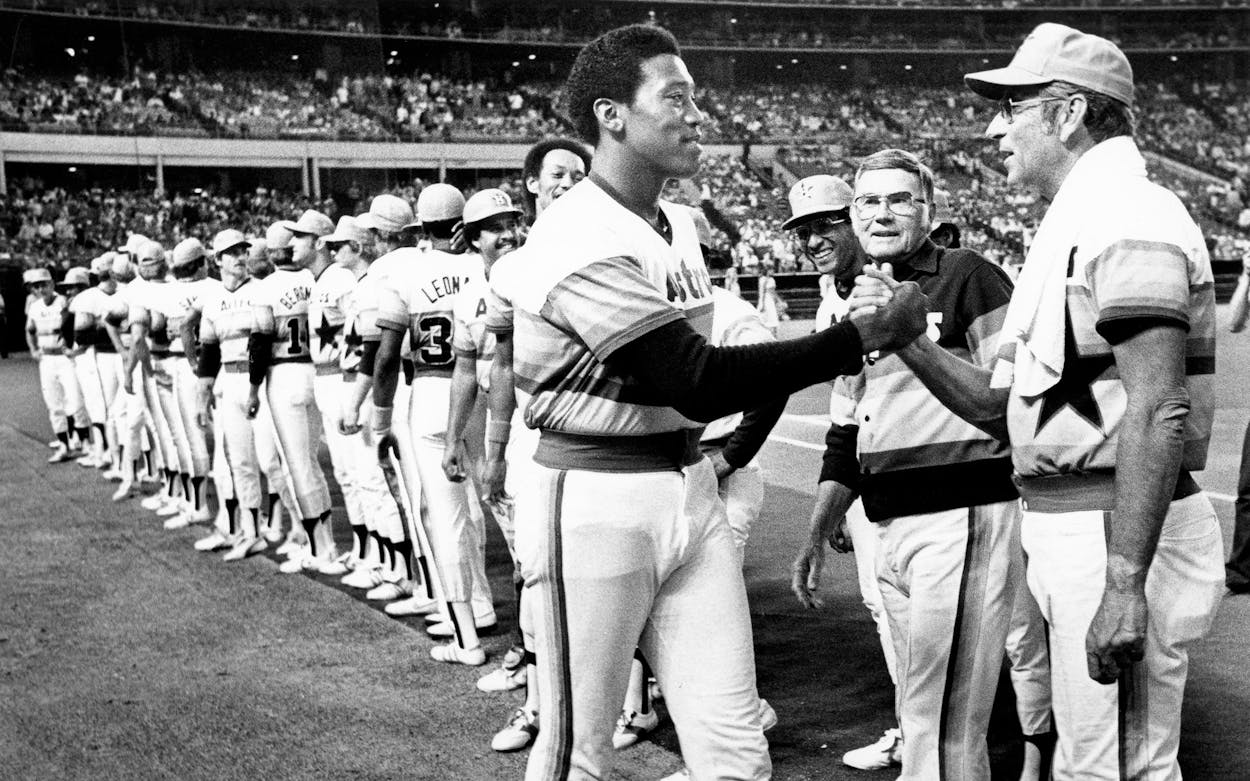

In 1980, he made his only All-Star Game after leading the National League through the first half of the season with a 1.90 ERA and .166 batting average against. He threw shutouts in three straight starts, and in a statement released last week, Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan said Richard’s 1980 season was “one of the best seasons a pitcher has ever had.”

“The thing about his size was, the plate is sixty feet six inches from the mound, but J.R. is throwing from fifty feet,” said Baker, who faced Richard. “He was all legs. You didn’t have much time to make up your mind, plus he was a little bit wild. He was the toughest guy I ever faced.”

The scary thing about Richard’s talent was that he may have only begun to harness his full range of abilities in that 1980 season, which turned out to be his last. “I don’t think I was in my prime,” he would say years later. “Remember I got a late start before I really got it together.”

He started that All-Star Game and pitched two scoreless innings and left with what was said to be an upset stomach. That turned out to be the final time he appeared in a major league game. For a couple of weeks preceding the All-Star break, Richard had been bothered by a dead-arm feeling and medical tests revealed he had a blood clot in his pitching arm. But he was cleared for workouts.

Around that time, he’d caused a stir in Houston by hinting he might be better off pitching elsewhere. Plenty of people in the Astros organization and the Houston media weren’t sure if he was having physical problems or playing up his injury to send the organization a message.

Richard was surely on the cusp of unimaginable riches on July 30, when he collapsed while playing catch at the Astrodome. Doctors saved his life, but his baseball career was over. Three weeks after the stroke, Sports Illustrated published a searing piece detailing the condition the once mighty pitcher found himself in:

James Rodney Richard is sitting up in bed in his room at Methodist Hospital in Houston last Friday afternoon, staring at a bowl of vegetable soup and stirring it with a spoon. He has just finished his second dish of mashed potatoes, leaving the asparagus and rolls, and now Kathy Burke, his private nurse, moves to his side. The nurse steadies his right hand as he raises a container of milk to his lips. “Now sip,” she says. He sips slowly through a straw. “That’s it,” she says. She turns and walks away. Lunch is over; a little party is about to begin.

And later in the story:

When Richard first came out of surgery, his speech was so impaired he had to write notes. His first to (Tom) Reich (his agent) was: “Black walnut ice cream. One quart.”

Richard attempted comebacks in 1982 and ’83, but his body wouldn’t allow it. After baseball, he worked an assortment of jobs, including preaching, construction, and selling cars. His career earnings—peanuts, compared with the eight-figure salaries of today’s best major leaguers—were soon gone. His second marriage ended in divorce. He bottomed out in 1994, when he was discovered sleeping beneath an overpass a few miles from downtown Houston.

“I had some people I knew when I was playing ball and I would go to their house and wash my clothes and eat, maybe spend a night or two,” he told the Times in 2015. “But some of those people had families, and I did not feel right just coming in. So I would go under the bridge, and that’s it.

“Everything at that point became a point of survival. You’re trying to survive, you have no transportation, no food, no finances. You ask yourself a lot of times, where do I go from here?”

He made it off the street with help from friends and the Baseball Assistance Team, an organization that provides confidential financial aid and other forms of support to ex-MLB players in need. In addition, Richard became eligible for a $100,000 MLB pension in 1995, when he turned 45.

When Richard became a public speaker, he hoped that in repeating his life story he might help others. He worked with Houston’s Lord of the Streets Episcopal Church as part of what he saw as his final mission.

“You can lay down and die or get up and keep living,” he said. “I just chose to get up and keep on living.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Obituaries

- MLB

- Houston Astros

- Houston