In 1970, when I was a junior high school student living in Wichita Falls, I rode one afternoon with a friend and his older brother to Archer City, a town located 25 miles away. At the time, Peter Bogdanovich was shooting a movie called The Last Picture Show, about some teenagers trying to find happiness in a desolate Texas town. Rumor had it that one of the actresses in the film, Cybill Shepherd, was going to be filming a nude scene that day. My friend’s older brother told us we had to be there.

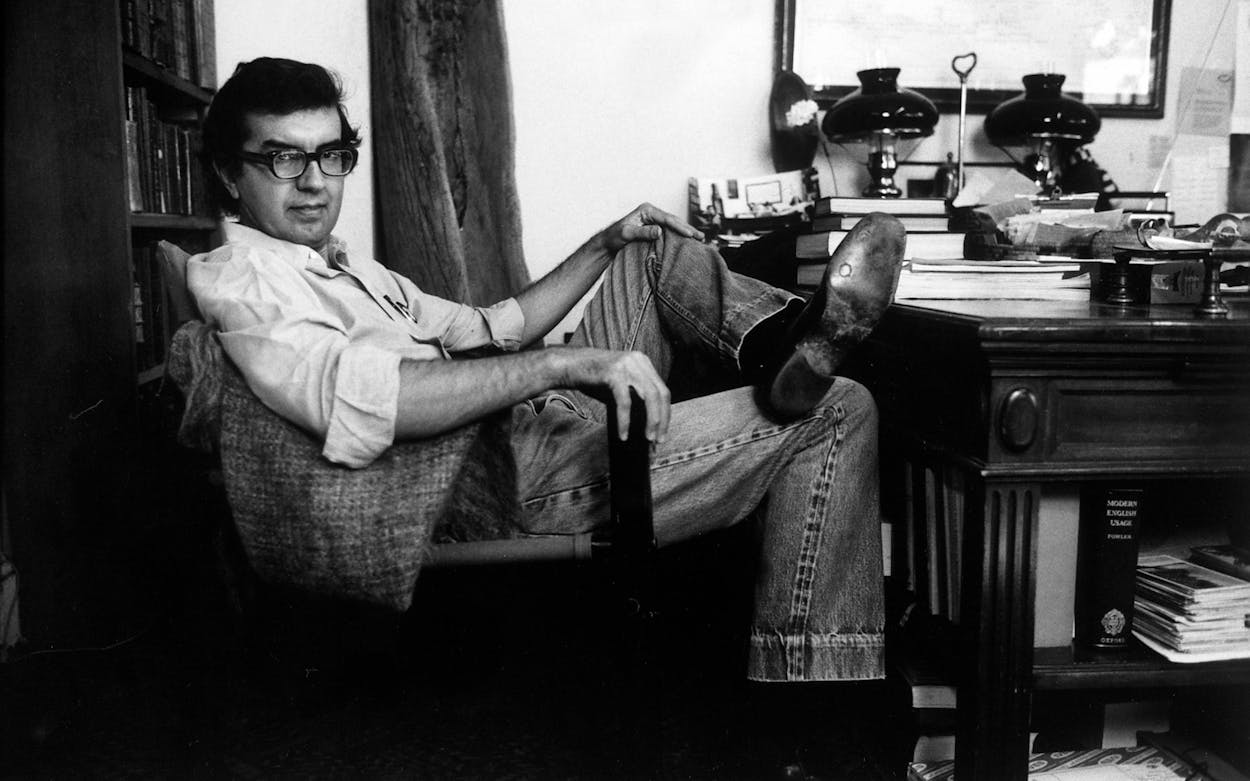

When we arrived in Archer City, the three of us gathered with other onlookers at the end of the street. We watched as the film crew moved equipment from one building to another. For the next hour, nothing else happened. Cybill Shepherd did not appear. We figured our trip was a waste of time. But just before we headed back to our car in defeat, several adults in the crowd began buzzing. One of them pointed at a thin young man quickly crossing the street. He had thick, tousled black hair and wore Buddy Holly–style glasses.

“That’s Larry McMurtry!” a woman exclaimed. Seeing the baffled looks on our faces, she explained that McMurtry was an Archer City rancher’s son and had written the novel on which the movie was based. “Hey, Larry!” someone else yelled. McMurtry turned and gave us a brief wave. I was amazed. I had no idea that a writer could be famous.

I went home, came across a worn-out paperback edition of The Last Picture Show, and devoured it. I was floored by the characters McMurtry had created, who were just like people I knew in real life. They talked the same way. They had the same problems. They stood around on Friday nights trying to think of something to do to entertain themselves. And most incredible was the fact that the novel—about Archer City, Texas, of all places—was being hailed as a major work of literature.

By college, I was an unabashed McMurtry fanboy. I wrote papers about him for my English classes in which I always pointed out that he and I were, more or less, neighbors. During my trips back to Wichita Falls, I made regular excursions to Archer City, hoping to run into him. In my early twenties, I decided to compose my own McMurtrian novel about a boy coming of age in rural Texas. “How hard could it be?” I asked, leafing through The Last Picture Show for the hundredth time. After learning that McMurtry wrote five double-spaced pages of fiction on his manual typewriter every day of the week, just after breakfast, I vowed that I would do the very same thing each morning before going off to my job as a reporter at a Dallas newspaper. I never got past the second chapter. How, I wondered, did McMurtry do it?

McMurtry, who was 84, died on Thursday of congestive heart failure, as his writing partner, Diana Ossana, confirmed. He spent his final days surrounded by Ossana; her daughter, Sara; his wife, Faye Kesey; his son, James; his grandson, Curtis; and Ossana’s three dogs, all of whom adored McMurtry. Just before he died, Ossana sent me an email. “I keep walking through my house and remembering so many things he did, where he’d sit, typing at the counter, staring out at the mountains for hours at a time,” she wrote. “I know I’ll survive, but at the same time, I don’t know how I’ll survive. This feels like someone is sawing off one of my limbs.”

McMurtry was not always the friendliest man. In 2016, when I visited him in Tucson and Archer City for a Texas Monthly story I was writing, he always seemed bored, and changed the subject whenever I asked him about his accomplishments. He grunted at my queries about his “writing process.” When I called him to ask follow-up questions, he got so tired of talking with me that he hung up the phone without saying goodbye. Not once did I ever hear him laugh out loud.

But, Lord, he was a lot of fun to be around. At dinners, he’d get wound up and talk about everything from eighteenth-century Russian poetry to the joys of Dr Pepper and Fritos. He passed on juicy gossip about movie directors, politicians, and best-selling authors. I felt cheated when he said it was time for me to leave because, of course, he had to get up early the next morning to write.

Day after day, he churned out the pages. The Archer City boy who grew up in a ranch house with no books turned out to be one of the most prolific writers in American letters. He published some thirty novels and fourteen books of nonfiction, wrote or co-wrote more than forty screenplays and teleplays, and produced reams of book reviews, magazine essays, and forewords to other texts. “Larry is like an old cowboy who has to get up in the morning and do some chores,” Ossana told me in 2016. “He has to get up and write. I don’t think he would know what to do with himself if he didn’t have something to write.”

I haven’t come close to reading all of McMurtry’s work. The only person I know who’s accomplished that Herculean task is Mark Busby, an English professor at Texas State University. Busby argues that McMurtry, more than anyone else, has shaped the way people see Texas. His novels about the fictional town of Thalia (Duane’s Depressed; Horseman, Pass By; The Last Picture Show; and Texasville, among others) are pitch-perfect depictions of the realities, and hilarities, of small-town Texas life. (When we spoke in 2016, Busby went so far as to compare the Thalia novels to William Faulkner’s great Southern novels about Yoknapatawpha County.) And the novels McMurtry wrote in the seventies about Houston, including All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers and Terms of Endearment, are, in Busby’s words, “brilliant and moving domestic dramas, something that no one was expecting from him.”

And then there’s Lonesome Dove, his 1985 novel about two retired Texas Rangers leading a brutal cattle drive from Texas to Montana in the 1870s. McMurtry had spent years railing against writers who produced clichéd novels about the Old West. He swore he would never stoop to writing a western. But he did, and the novel he produced gripped the public’s imagination. Lonesome Dove won the Pulitzer Prize and sold nearly 300,000 copies in hardcover and more than a million copies in paperback. It spawned a sequel as well as prequels, and became one of the most popular miniseries of all time, starring Tommy Lee Jones and Robert Duvall. To Texans, went one joke, Lonesome Dove was the third-most-important book in publishing history, right behind the Bible and the Warren Commission Report.

Even when McMurtry was writing novels set in Los Angeles or Las Vegas or Washington, D.C., Texans were always a part of the narrative. He wrote of a former rodeo cowboy who became a womanizing antiques dealer (Cadillac Jack) and an erstwhile University of Texas football player who later became a Hollywood striver (Somebody’s Darling). Just before he fell ill, he was working on two more Texas-based stories—one a western based on the life of the cattleman Charles Goodnight, and the other a modern-day novel of manners about a Fort Worth socialite. (He never published them.) For all of the acerbic criticism of mundane Texas life and literature that marked his essays, the man loved Texans, big and small.

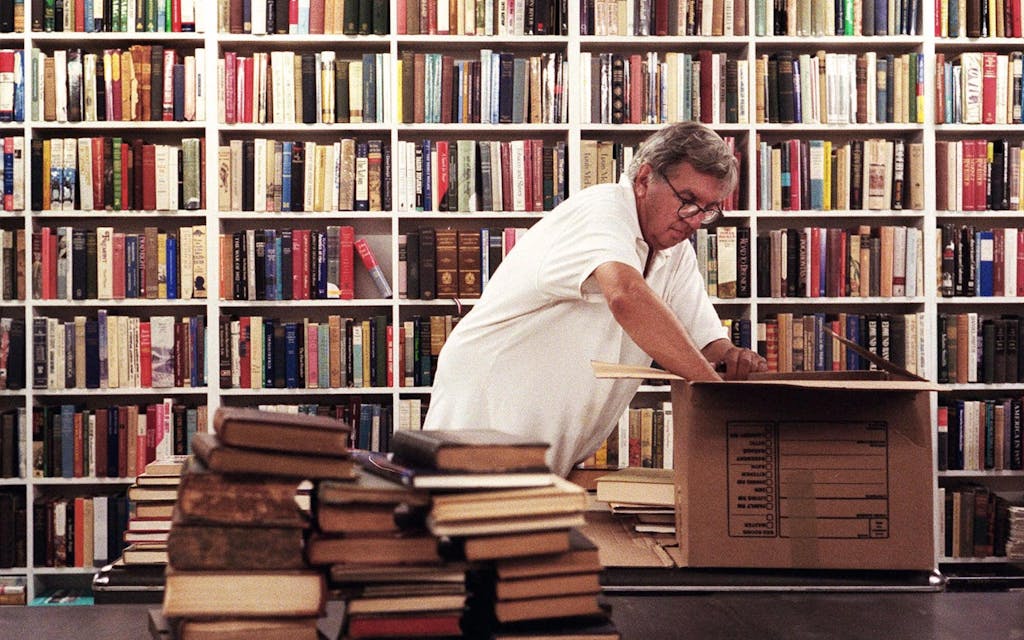

McMurtry took his knocks for writing too much and not editing what he had written, but even his fiercest critics admitted that he had a Dickensian ability to spin a yarn. Besides the Pulitzer, he won an Academy Award with Ossana in 2006 for Brokeback Mountain, their adapted screenplay based on Annie Proulx’s story about two gay ranch hands. (McMurtry famously wore blue jeans to the ceremony and had a less than ecstatic response while accepting the Oscar.) When he wasn’t writing, he served as the president of PEN America, the association of prominent writers. He operated a massive second-hand bookstore that, at its peak, spread across four buildings in downtown Archer City.

Periodically—this is one of my favorite details about him—he’d rent a Lincoln Continental, drive across the country, visit a friend or two, drop off the car at a rental facility whenever he got tired of driving, pay the exorbitant drop-off charge, and then fly home. I asked him what he did with all his dirty clothes on those excursions. Would he stop at a laundromat and clean them? Oh, hell no, he said. He’d stuff the clothes in a Federal Express box and ship them back to his house.

When I went to see him in 2016, he seemed weary. He had had a couple of heart attacks. He stumbled a few times. His memory slipped. “Old age comes on apace to ravage all the clime,” he said at one point, quoting the eighteenth-century Scottish poet James Beattie. “And old age is doing what it can to ravage me.”

I tried to get McMurtry to reflect on the end of his life. I asked him how he felt about the inevitable day that was approaching when he would no longer be around to write his five pages. But he was having none of it. I changed the subject slightly and asked where he wanted to be buried. He said he had bought a plot at a Wichita Falls cemetery, but he recently had begun thinking about cremation and keeping his ashes in an urn. “I expect there will be a little memorial service of some kind, and then my ashes will be placed unobtrusively on a shelf in one of the bookstores in Archer City,” he said.

“Your ashes forever among books?” I asked, hoping my question might spur McMurtry to say something sentimental. Predictably, he refused to rise to the bait.

“Well,” he said, “maybe people will want to come up to Archer City and stare at my urn. And maybe they’ll buy more books.”

Update: This story has been updated to reflect McMurtry’s cause of death.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Books

- Larry McMurtry

- Houston

- Archer City