When Lars Eighner’s memoir, Travels With Lizbeth, was published nearly thirty years ago, it was a literary and media sensation. There was a review on the front page of the New York Times Book Review, a People profile, and an interview on NPR’s Fresh Air. Eighner and his labrador mix, Lizbeth, appeared in a segment of On the Road With Charles Kuralt. “It was a first-time author’s dream,” said Steven Saylor, Eighner’s agent. “But Lars was not in his element; all the press and interviews and the travel were hard for him.”

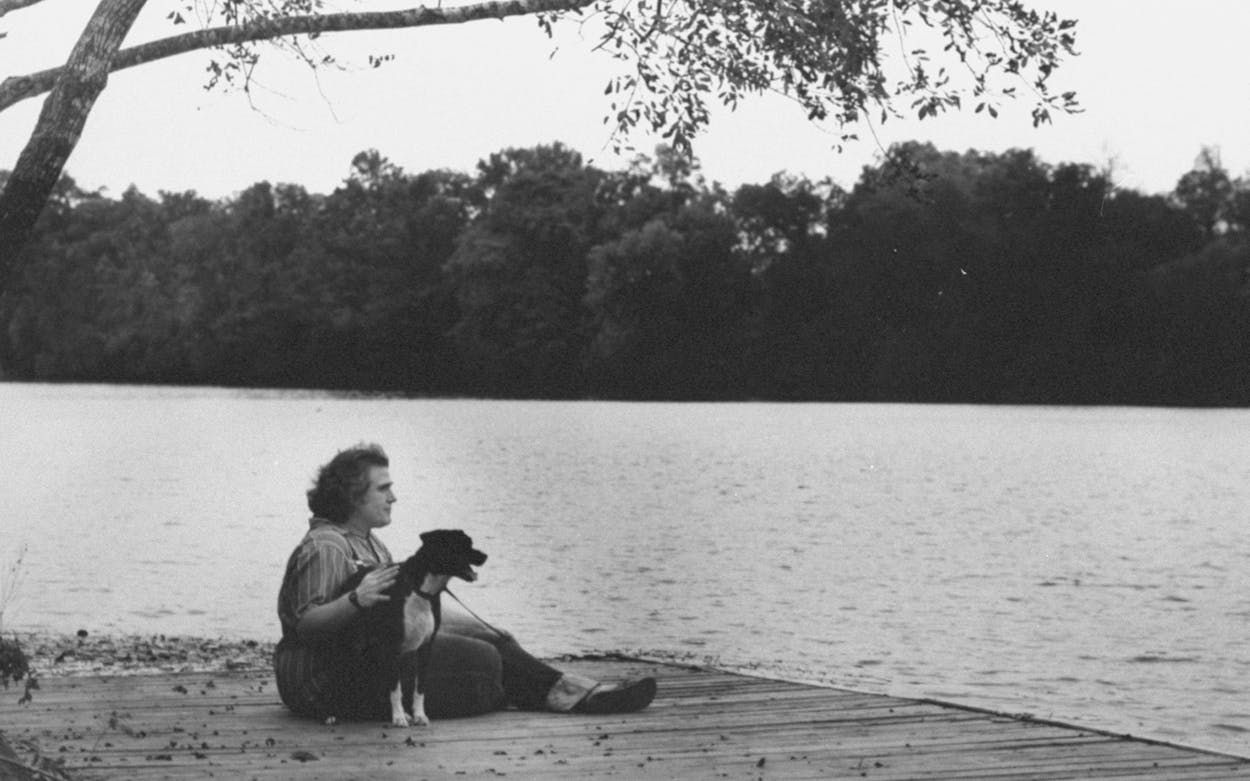

A gentle giant of a man who was reclusive by nature, Eighner had fallen gradually into homelessness after quitting his job at the Texas State Hospital, in Austin, and attempted to support himself by publishing gay erotic short stories. He didn’t set out to write about scavenging in dumpsters—he just wrote what he knew. But his book, written on a portable typewriter in an abandoned bar in Austin, struck a cultural nerve. “This book takes us into the profound depths of that other country that lies all around us on the streets,” wrote Jonathan Raban in the Times. “In lavish, patient detail, it recreates the grammar, point of view and domestic economy of the unhoused life, and if there’s any justice in the world it should guarantee its author a roof over his head for the rest of his days.” For a time, that prophecy came true. With proceeds from the book, Eighner was able to rent a house in Austin with a yard for Lizbeth, but that stability was short-lived.

I was taken aback when I read an obituary for Eighner in the New York Times in mid-February. Laurence Vail Eighner Hexamer (he had taken his husband’s name) had died in Austin on December 23, 2021, at the age of 73. Born in Corpus Christi and raised in Houston, he spent most of his adult life in Austin. He experienced homelessness again in the late nineties, after the book money ran out, and a group of Austin writers came together to raise money for him. At the time of his death, Eighner and his husband, Cliff, were living in a small one-bedroom apartment, and according to a GoFundMe page the couple had set up a few years ago, Eighner, who suffered from poor health, had been mostly bedbound for years. Still, I was surprised that nearly two months had passed before there was news. Had everyone forgotten about him?

Lars Eighner and I crossed paths not in Austin, where I had been a UT student during the time he was homeless, but in New York City. Fresh out of a graduate program in creative writing, I had just started a job as an assistant publicist at St. Martin’s Press, the publisher of Travels With Lizbeth, and one of my first tasks was to write a press release for the book. I took an advance copy home and devoured it: it was literary, wickedly funny, and touching (especially his love for Lizbeth) but never sentimental. And the erudition: in one passage, he invokes Plato’s allegory of the cave to describe an especially terrifying night; in another, he critiques college papers he’s dug out of the trash. “I can hardly believe what passes for an A these days,” he tut-tutted. (He attended classes at Rice and UT-Austin but didn’t obtain a degree.) Even many of the sex scenes—hurried encounters in park restrooms and the occasional hand job exchanged for cash—were described with almost Victorian restraint. I had never read anything like it. But the book was also a testament to Austin’s LGBTQ community; even while struggling to survive, Lars donated to AIDS food banks, and he got help from the community regularly, including when Lizbeth was impounded and he couldn’t pay to spring her.

As his media tour came together, we spoke on the phone regularly (his slow drawl made me homesick for Texas), and I met him one day when I picked him up at his New York hotel to go to a radio interview. My first impression was that he was one of the most imposing men I’d ever seen, and with his longish, side-parted hair, he looked a little like Tiny Tim. We took a taxi and he was nervous and a bit crabby and a terrible passenger, something he wrote about in the book. He cried out and gasped every time the cab sped up or stopped. I remember thinking that day, and several times on the phone, that he could be difficult and even dramatic. But I wanted to confirm those memories. I called Saylor, in Berkeley, California, to talk about those days. “Oh yes, Lars could be a bit of a crank,” he chuckled. “But oh, his talent . . .”

Saylor, who is also from Texas but has lived in California for decades, had been editing a couple of gay magazines in the Bay Area in the eighties when “I started getting these things from this writer in Austin—so exquisitely written, like they were ready for the New Yorker. I wanted to meet him.” Thus began an editorial relationship that would last for decades. Eighner wrote Saylor letters from the road and sent him samples of essays. Saylor took one of them—a guide to scavenging for food that was also a critique of contemporary society—and got it published in the Threepenny Review, a San Francisco literary magazine, in 1991. “On Dumpster Diving” was also excerpted in Harper’s shortly after, and Travels With Lizbeth grew from there.

Eighner reportedly earned around $100,000 from the book, and he got royalty checks twice a year from the heavily anthologized “On Dumpster Diving.” Saylor managed to get a couple of his earlier works, the comic novel Pawn to Queen Four and Gay Cosmos, a collection of essays on queer theory, published in the wake of Lizbeth, to modest sales, but after that, the well ran dry. “Lars wasn’t like other people who had a drive; he wasn’t going to be a successful A-list writer,” said Saylor, attempting to explain Eighner’s lack of ambition or business sense (which are not qualities a lot of great writers have anyway, he added). “He didn’t buckle down and keep producing. He did this one thing that hit the bull’s-eye.” In an afterword to the 2013 edition of Travels With Lizbeth, Eighner admitted that he wasn’t good at the publishing game. He wrote that his book was “sui generis” and that he had “no argument with anyone who called it a fluke.”

I left publicity for an editorial job at a magazine not long after working with Lars, and occasionally, I’d see a story about him and hoped he was doing well. I moved back to Austin with my family in 2016 but hadn’t thought of Lars much for years until last year, when my daughter was assigned to read “On Dumpster Diving” for her freshman English class. I told her my story of how I had known him a little, many years ago. She wrote in her review that he’d made her think about how much we waste as a society and our unacknowledged privilege (cue proud parent moment). She also loved that he took a discarded embroidery project he found in a dumpster, pulled out the threads, and created his own design. I had forgotten that detail, but it sounded very Lars Eighner. Learning of his death just a few months later made me regret not reaching out. I would have gladly donated to his fundraiser.

Saylor told me that he had been behind the Times obituary; he’d gotten an email from Eighner’s husband a few weeks after he died. He has also held on to several boxes of Eighner’s letters and writings, including an unexpurgated original manuscript of Travels With Lizbeth (all 662 pages of it). Eighner mailed all of it to him some years ago, when he was worried about becoming homeless again. Saylor hopes to donate the collection to the Harry Ransom Center at UT, so that Eighner’s work can live on. “Maybe some more books can come of it—I can see a scholar going in there and digging through all of that.”

- More About:

- Books

- Obituaries

- Homelessness

- Austin