Picture this: A filmmaker with no major credits to his name gets it in his head to make a black and white film set in the middle of nowhere. He’s a city boy; the movie is a quiet evisceration of small-town life, based on a novel by a native son. The director casts an assortment of veteran character actors and young nobodies. The project sounds quixotic at best. But this is 1971, the heart of the New Hollywood era, when studio heads are, for a brief, glorious time, trying new things and trusting young directors. The movie is a hit, earning eight Oscar nominations, and wins for two of those veteran character players.

This is the story of The Last Picture Show. Released fifty years ago this month, Peter Bogdanovich’s breakthrough has since become an indelible Texas movie, a stark, poetic, loose-limbed, and ultimately very sad portrait of lonely Lone Star life. It’s set in fictional Anarene, which is based on the novel’s Thalia, which in turn is based on novelist Larry McMurtry’s hometown of Archer City, where the film was shot. (Archer City’s Royal Theater will host a public tribute to McMurtry, followed by a free screening of the movie, on October 9.) The Last Picture Show is both beautifully specific and universal, evoking small towns throughout North Texas in the years following World War II, or just about any other time. “One thing I know for sure,” offers Eileen Brennan’s Genevieve, who runs the local diner. “A person can’t sneeze in this town without somebody offering them a handkerchief.”

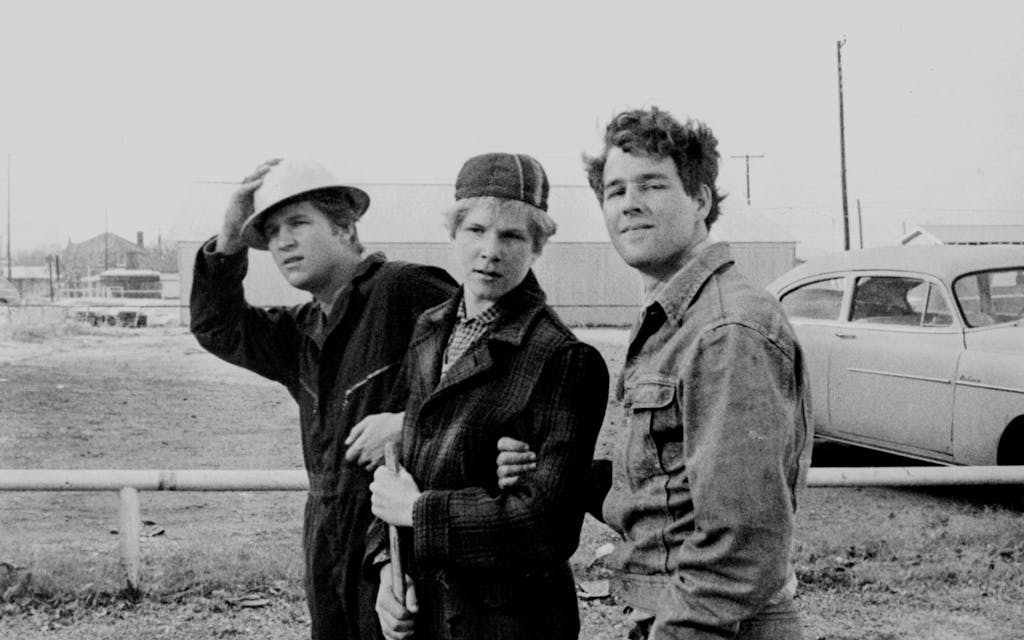

The year is 1951, and high school is winding down for Sonny (Timothy Bottoms) and Duane (Jeff Bridges, in his first major movie role). They’re knockabout, horny boys with no idea what’s next in life. Anarene’s social life, such as it is, centers on the pool hall, the diner, and the movie theater, all owned by Sam the Lion (Oscar winner Ben Johnson), seemingly the only adult in town who isn’t compromised or morally corrupt. Our protagonists drift from hangout to hangout, making poor romantic decisions: Duane dates the snooty, beautiful rich girl Jacy (Cybill Shepherd, in her first screen role), whose embittered mother (Ellen Burstyn) wants her nowhere near anyone without money. Sonny, meanwhile, is carrying on with Ruth Popper (Oscar winner Cloris Leachman); we are led to believe her husband, the high school football coach, is a closeted gay man.

There is no idealization of small-town living in The Last Picture Show, nor is there anything maudlin. McMurtry, who died in March, was above all a truth teller. Archer City is a little more hopping than it was in 1951, but not by much; its population still hovers in the 2,000 range, although Booked Up, the bookstore McMurtry started in Washington, D.C., has proved to be an enduring attraction. Still, it’s the kind of town from which people seek to escape, not arrive. The quickest way to get out of Anarene may be to die, as both Sam and his young charge, the simple-minded sweeper boy, Billy, do by the film’s end. Duane escapes by heading off to the Korean War. Jacy heads off to Dallas, a city with no shortage of rich husband material. Sonny, the kindest heart among the kids, just seems to be stuck. If you want to catch up on these characters several years down the road—always a pleasure with McMurtry’s writing—check out the (admittedly inferior) follow-up novel and its 1990 movie adaptation, Texasville.

The black and white of The Last Picture Show isn’t creamy or lush. It’s stark and unforgiving, like the blue norther that always seems to be blowing through in the winter, prompting the residents to rub their hands together and seek a warm body. (From the novel: “It occurred to Sonny that perhaps people called them ‘blue northers’ because it was so hard not to get blue when one was blowing”). The wind howls something fierce, over and under dialogue, creating a pervasive sense of inhospitality from which the characters can’t hide.

All of this might lead you to think the movie is depressing. It’s not. There’s too much humanity flowing through Bogdanovich, and McMurtry for restrictive emotions to take root. The film is empathetic and forgiving at its core, and this comes through in the tone the town takes toward Duane and Sonny after the football team’s humiliating, season-ending loss. “This is what I get for bettin’ on my own hometown ball team,” Sam the Lion mutters as he pays his bet to the town’s cocky oil tycoon, Abilene (Clu Gulager). “I oughta have better sense.” “Wouldn’t hurt to have a better hometown,” quips Abilene. Such moments play like gallows comedy. Self-awareness and lethargy walk hand in hand through The Last Picture Show—an assumption that there has to be something better out there, but that the characters have no idea what that might be. The film’s sense of ennui, especially as it relates to young people, is timeless.

Author Steve Yarbrough, in his book about the movie, recalls borrowing the novel from a friend as a young man and asking what it was about. “Among other things,” his friend replied, “it’s about football and sex.” Yarbrough was disappointed that there wasn’t much football. But sex? Oh yeah. Neither novel nor film shies away from the carnal. It’s all over the screen (and off, as it turned out: Bogdanovich and Shepherd fell in love on the set, and the director ended up leaving his wife, the film’s production designer, Polly Platt). The movie had the nerve to show that teenagers in small Texas towns, like anywhere else, talk about and do their best to have sex. Filmmakers had caught on to this fact by 1971; the New Hollywood was largely about breaking previously established boundaries. Still, there’s something jarring about seeing these taboos broken in black and white, in a small Texas town.

And they’re broken pretty brazenly. Sonny breaks up with his girlfriend because she won’t go all the way, but not before we see him playing with her breasts. Jacy attends a skinny-dipping party with other rich kids; later castigates Duane for his failure to perform; and ends up having sex with Abilene, who’s also sleeping with her mom, on a pool table. Duane, Sonny, and their friends take Billy, the simple-minded sweeper, to lose his virginity to a grotesque prostitute, who ends up bloodying his nose (Sam the Lion is irate). This last instance is downright cruel, but the film amply illustrates that extreme boredom, and ineffectuality, can readily lead to cruelty.

It’s not just the youngsters who feel the sting of loneliness here. Leachman is heartbreaking as Ruth Popper, emotionally run-down from a sham marriage and eager to find solace in the arms of the innocent Sonny. The forbidden relationship, which everyone in town knows about, feels less like a transgression than a desperate cry for help. It also sets up the final, deeply resonant lines of the film, which somehow sum up everything we’ve seen in the previous two hours.

Could The Last Picture Show ever be made today, for the big screen, in black and white, with journeyman actors, future stars, and an unproven director, in a tiny Texas town? The question practically answers itself. Bogdanovich caught the movie world by surprise, although he had some heavy hitters in his corner from Hollywood’s Golden Age. It was John Ford, a friend and the subject of Bogdanovich’s documentary Directed by John Ford, who reportedly persuaded Johnson to play Sam the Lion (Johnson was hesitant because he thought the character did too much talking). And it was another famous friend, Orson Welles, who encouraged Bogdanovich to shoot the movie in black and white, the better to capture a depth of field that both filmmakers felt couldn’t be achieved in color.

The Last Picture Show is very much of Texas—perhaps only Giant is more emblematic of the state—but it also transcends Texas. There may be no more powerful film about growing up with nowhere to go. The Last Picture Show’s way of life may be dying, but the movie will never fade away.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Larry McMurtry

- Archer City