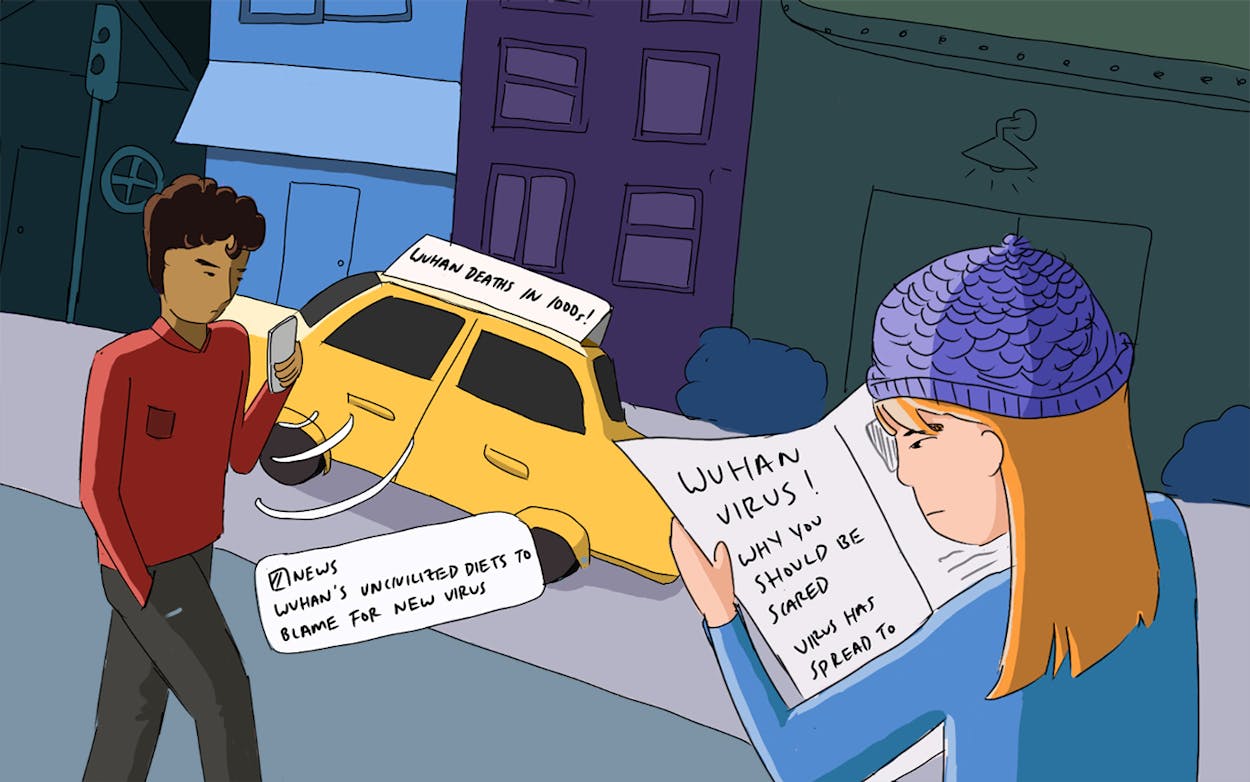

In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, discrimination toward Asian Americans has surged across the United States. According to the Asian Pacific Policy & Planning Council, the group received upwards of 1,100 reports of coronavirus discrimination—which included instances of verbal harassment, shunning, and physical assaults—within a month of opening their Stop AAPI Hate reporting center. Illustrator Laura Gao, who’s from Wuhan, China, and grew up in the North Texas suburbs, noticed racist rhetoric coming from public figures and media outlets—many of whom have called the new coronavirus the Wuhan virus—and experienced firsthand someone making unwelcome comments about her race. Gao’s hometown of Wuhan, unfamiliar to most Americans until early this year, was now suddenly known around the world.

Gao, who in her spare time often illustrates comics about her heritage and about modern romance, decided she wanted to counter the derogatory remarks she’d heard about Wuhan by creating a comic about it titled “The Wuhan I Know.” “I wanted to express my story about grappling with my identity as being Wuhanese and Chinese,” Gao says. “I also wanted to highlight why I’m proud of my city and my people.”

The comic starts with her family immigrating from Wuhan to Texas when Gao was three years old. She notes that to the Texans they met shortly after moving, “Wuhan was more foreign than Mars.” People were often uninterested in learning about the city and assumed she was from Beijing or Shanghai, too. Gao goes on to explain that Wuhan, often nicknamed the “Chicago of China,” is in fact one of the fastest-growing cities in China, and is home to more people than New York, London, or Tokyo.

In it she also illustrates Wuhan’s history and architecture, including its most famous landmark, the Yellow Crane Tower. Known for inspiring an eighth-century poem written by Cui Hao that’s often labeled as one of the greatest works in the Chinese poetic canon, the traditional tower has existed in various forms since AD 223, and Gao writes that “in the sun, it shines like gold.” The comic also delves into the part of Wuhan that Gao misses most: its street food. Gao reminisces on waking up in Wuhan to streets lined with vendors selling her favorite local snacks, including re gan mian, a hot and dry noodle dish made with sesame paste, and doupi, sticky rice with bits of meat and vegetables wrapped in bean skin then fried.

Gao told me that she was supposed to travel to Wuhan in late January to celebrate her grandmother’s eightieth birthday, but her flight was canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic. While she’s illustrating parts of Wuhan often left out of media narratives, Gao’s art also is a way for her to travel virtually to her hometown until she can return to visit family.

When Gao finished her comic, she initially hesitated to post it on social media. “As someone who is on Twitter a lot and sees what people are saying about Asians across the platform, I was afraid that people would dogpile on my feed,” she says. With time, she increasingly felt that the importance of sharing her story outweighed her fears about it. After sharing the illustration on Twitter last month, Gao received an outpouring of support—the tweet has gained thousands of likes and retweets since she posted it—with some people expressing that they now want to visit Wuhan after the pandemic subsides around the world. Others related to Gao’s story and shared their own stories of experiencing racism.

Gao, who works for Twitter as a product developer, later caught the attention of her colleagues. After her tweet went viral, Twitter’s creative team reached out to her asking if they could work with her to animate her comic. “Ever since coronavirus, we’ve seen a lot of anti-Asian, xenophobic, and racist comments and tweets, so we wanted to make sure that as a company, we were also finding good examples of what is good behavior on the platform,” Gao says. She worked with the creative team by adding some new drawings and adding her narration to the comic, which was posted on the @TwitterAsians account on April 10.

"Instead of remembering my hometown as the 'the place where COVID originated', I want people to respect Wuhan as a city with beautiful history, culture, and people. This is the Wuhan I know." – @heylauragao pic.twitter.com/pnnhou3Kjt

— Twitter Asians (@TwitterAsians) April 10, 2020

For Gao, this experience has been a prescient reminder of just how important storytelling is right now. “If you’re one of the people who historically has been disenfranchised and did not have a voice, now we are able to,” Gao says. “I was able to create a comic sharing my deepest emotions about how I feel right now and share it with anyone who wants to hear it and relate to me. Or if they can’t release it, they can at least acknowledge a lot of my emotions and understand.”

- More About:

- Art