Lawrence Wright had his road-to-Damascus moment in 1979 in Gruene, the quaint Hill Country town halfway between San Antonio and Austin. At the time, he was living in Georgia, writing for a regional magazine and freelancing for various national publications. Although the Oklahoma-born Wright had spent his teenage years in Dallas, where his father was a bank president, he’d escaped the state’s centripetal pull once he graduated from high school, in 1965, leaving first for college in New Orleans and then accepting a teaching position at the American University in Cairo before eventually settling into a journalistic career in Atlanta.

But as he explains in God Save Texas: A Journey Into the Soul of the Lone Star State (Knopf, April 17), he was on assignment for Look magazine when he wound up one evening at Gruene Hall, the legendary music venue established in 1878. He had a night many Texans would die for: “A band called Asleep at the Wheel was playing Texas swing. A young man named George Strait opened for them. Dancers were two-stepping; the boys had longnecks in the rear pockets of their jeans and the girls wore aerodynamic skirts.”

Wright felt the stirring of a new romance with the Lone Star State that evening, and within a year he had accepted a staff writing gig at Texas Monthly and moved with his wife and young son to Austin, where he has lived since. In the years that have followed, he’s become one of the nation’s most respected and versatile writers, the author of a novel, multiple screenplays, and nine works of nonfiction, including The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 2007 (and is the subject of a current Hulu miniseries on which Wright served as an executive producer). But save for portions of a 1987 memoir, In the New World, Wright has rarely scrutinized Texas in print, reporting instead for the New Yorker—where he has been a staff writer since 1992—on domestic politics, U.S. foreign relations, and Scientology, the subject of his 2013 book, Going Clear, which incensed many adherents with its unsparing indictment of the faith and its founders. God Save Texas turns the same critical eye to his home state and seems likely to provoke a similarly passionate response.

As Wright notes, “Writers have been sizing up Texas from its earliest days, usually harshly.” For evidence, he cites, among other narratives, the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted’s 1857 classic, A Journey Through Texas, with which Wright’s new book has some points in common. For one thing, both are journalistic accounts of meandering travels across this state, enlivened by encounters with colorful locals. (Olmsted, who won the design competition for Manhattan’s Central Park the year after he published A Journey Through Texas, was on assignment for the New-York Daily Times—which later dropped the hyphen and the “Daily.”) Each writer also had company on his travels: Olmsted was joined by his tubercular younger brother, John, while Wright’s frequent sidekick is the esteemed Austin novelist (and Texas Monthly writer-at-large) Stephen Harrigan, a close friend to whom God Save Texas is dedicated. But above all, the reporting of Olmsted and Wright, though separated by more than 160 years, leads to the same conclusion: Texas, because of its size and particularly its spirit, has a heavy hand on the national tiller.

But where Olmsted worried about the state’s ardent embrace of slavery, which he feared would encourage other western territories to welcome the peculiar institution, it’s the dreadful example presently set by Texas lawmakers that concerns Wright. As he explains: “I think Texas has nurtured an immature political culture that has done terrible damage to the state and to the nation. Because Texas is a part of almost everything in modern America—the South, the West, the plains, Hispanic and immigrant communities, the border, the divide between the rural areas and the cities—what happens here tends to disproportionately affect the rest of the nation. Illinois and New Jersey may be more corrupt, Kansas and Louisiana more dysfunctional, but they don’t bear the responsibility of being the future.” What awaits America, Wright suggests, is unending partisan combat, in which gerrymandered arch-conservatives impose an ideological agenda increasingly at odds with a more centrist electorate. (At times it’s not crystal clear whether he regards Texas as a microcosm of our country’s problems or a cause of them. Perhaps, one suspects, it’s both.)

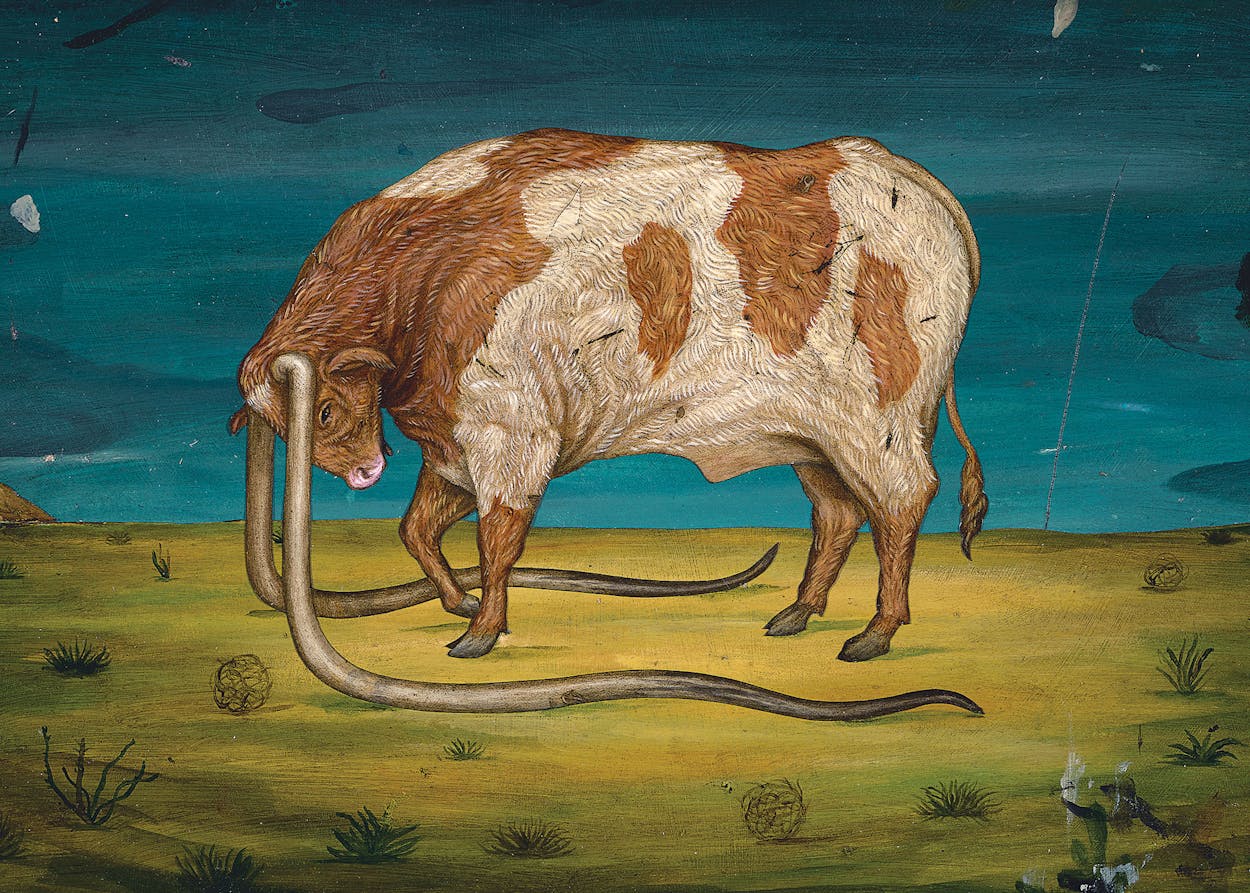

A Big Night in Ol’ San Antone

Frederick Law Olmsted’s “A Journey Through Texas” includes this alarming description of street life in San Antonio: “Where borderers and idle soldiers are hanging about drinking-places, and where different races mingle on unequal terms, assassinations must be expected.”

Much of what Wright describes will be familiar to readers of this magazine, especially to those who followed the 2017 proceedings of the 85th Texas Legislature, which—highlighted by the failed bathroom bill—seem to represent, to Wright, our political nadir (or perhaps just the freshest wound among many). As such, one suspects that the intended audience for God Save Texas is coastal cosmopolitans, whether in New York or Los Angeles, who will probably have a bifurcated reaction to the book. On the one hand, they may take glib satisfaction in the notion that they were right all along in their misgivings about Texas: it really is an arrogant, mean-spirited place that thumbs its nose at regulation and undermines efforts to aid the least of its brethren. At the same time, those very scolds will likely recoil in horror at Wright’s thesis that Texas represents an existential threat to much of what they hold most dear. As Wright tells us, the Norwegians, of all people, arrived at this insight some time ago, captured in their expression “Det var helt texas,” which means “It was totally bonkers.” Easy for them to say in Oslo, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. Bostonians, San Franciscans, and even Austinites may be less sanguine.

Wright’s tone throughout the book conjures nothing so much as a series of loosely connected diary entries by a spouse reporting from inside a troubled marriage. After several decades of togetherness, the heady romance of those Gruene Hall days has waned, replaced by disappointment and frustration. God Save Texas is a pretty one-sided dispatch, which Wright himself admits. His slant is perhaps most evi-dent in a chapter describing “two different states [that exist] at the same time: AM Texas and FM Texas.” The former “speaks to the suburbs and the rural areas—Trumpland . . . Paranoia and piety are the main items on the menu.” FM Texas, meanwhile, with which Wright identifies, “is the silky voice of city dwellers in the kingdom of NPR . . . progressive, blue, reasonable, secular, and smug—almost like California.”

He tries dutifully to understand the other side’s explanation of how it took over, as when the GOP operative (and liberal bête noire) Karl Rove pulls up a chair at one of Wright’s weekly breakfast gatherings of writers and thinkers and proceeds to dissect the Republican vise grip on the state (Democrats have not won a statewide election since 1994). Yet it’s clear that Wright considers the AM listeners hopelessly wrongheaded and—despite their congenital Texan friendliness (which he describes as “a sort of [statewide] mandate”)—a formidable roadblock to national development, given the state’s lopsided sway.

All of this might lead a reasonable person to wonder just why it is that Wright has stayed wedded to Texas all these years. He has asked this question of himself, acknowledging that he sometimes dreams of divorcing the Lone Star State and running off to Montana or the Mediterranean coast of Spain. His network of close friends in Austin is surely a big part of why he remains. But just as much, it seems, is the state’s beguiling “Texceptionalism,” characterized by its “sense of its own apartness,” its location at a geographic crossroads, and—perhaps especially for a keyboardist in a blues band called WhoDo—its whopping, even obscene production of homegrown musical talent, including luminaries such as Buddy Holly, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Janis Joplin, Willie Nelson, and Roy Orbison, whom Wright holds in particularly high regard. Texas, he notes, boasts “a culture that is still raw, not fully formed, standing on the margins but also growing in influence, dangerous and magnificent in its potential.”

In short, it matters, and deeply. Having recently chosen his plot in the state cemetery (an honor reserved for exceptionally distinguished Texans, ranging from Stephen F. Austin to Ralph Yarborough), Wright will forever enjoy a front-row seat from which to view the state’s evolution. Not even in death will they part.

Andrew R. Graybill is the chair of the history department and co-director of the William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies at Southern Methodist University.

- More About:

- Books

- Lawrence Wright

- Austin