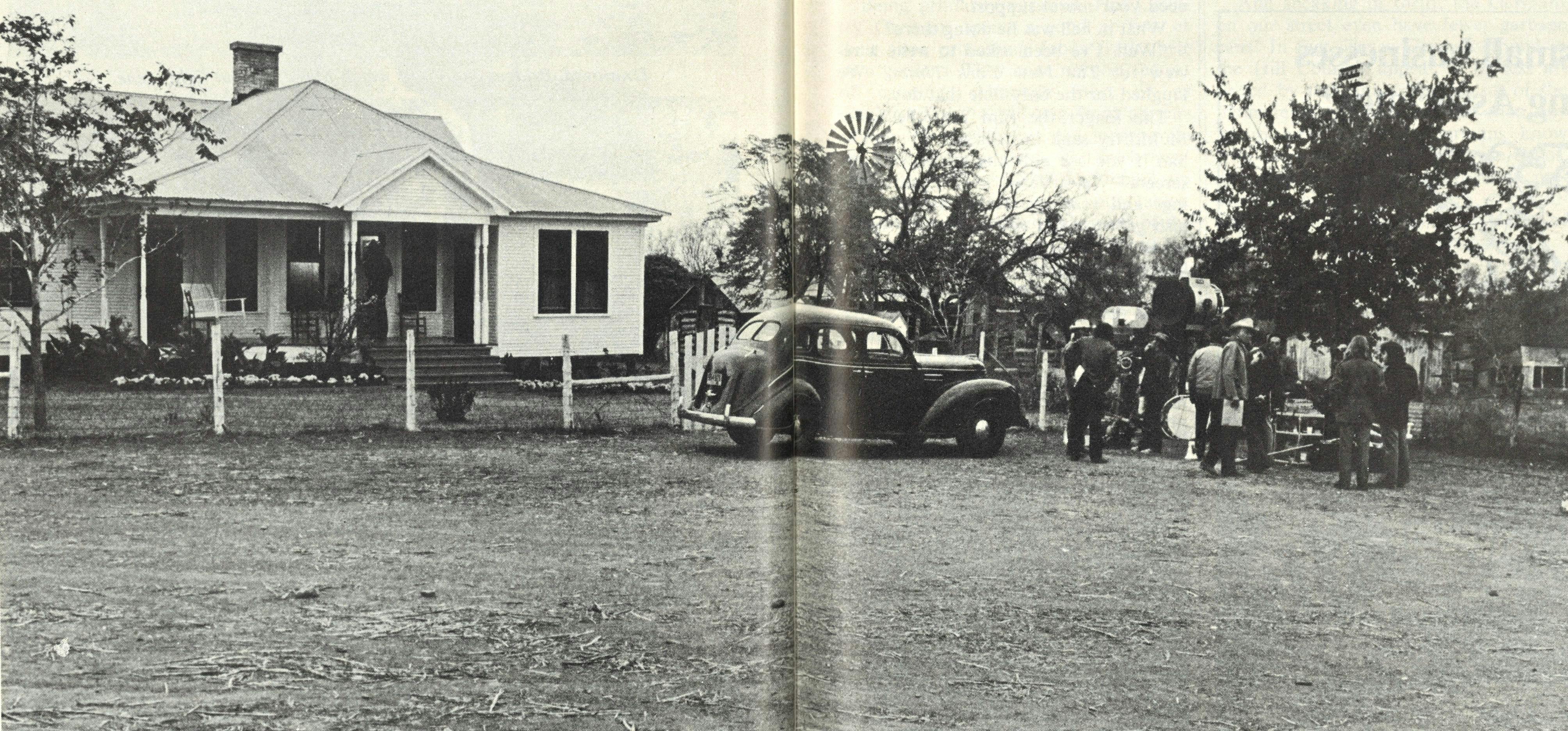

A little over a year ago the movie folk came to Texas—to Bastrop—to film Larry McMurtry’s Leaving Cheyenne, which remains my favorite among that good writing man’s novels of the old home state. Life magazine offered me money to write what I saw of Tinseltown’s efforts to capture McMurtry’s Texas on film. Perhaps foolishly, I took it.

About a month later, while I was accomplishing some real serious mid-afternoon research over a beer at Scholz’s in Austin, a New York lawyer tracked me down to report a death in the family: Life, as of two hours earlier, had expired. But to assuage my grief, I could keep the money.

I also kept my notes and memories against the day with Molly, Gid and Johnny—the shooting title—might be loosed upon an unsuspecting world. Well, neighbors, it soon will be, under the title Lovin’ Molly (which won out, at the final gun, over The Wild and the Sweet) and unless you are careful you soon may find yourself trapped with it in some Texas theater. Should you find more than a modicum of true Texas in the film, excluding John Henry Faulk’s bit role—why, then, I’ll buy you a two-dollar play purty. Lovin’ Molly has no sense of Time or Place; a curious development, indeed, when you consider that Larry McMurtry’s writing strength derives from evoking Time-and-Place about as well as you will find it done this side of Faulkner.

McMurtry writes of a real and human Texas. It is that part I know best—“my blood’s country and my heart’s pastureland,” he puts it—where the land is flat, the people narrow, and their small, pinched lives beyond even Hollywood redemptions. Tales of “legendary” Texas, blessedly, are not McMurtry’s cup of Pearl: not for him blazing six-guns, noble Pioneers taming the land by killing Indians, granite-jawed sons of the Alamo, the excesses of the Big Oil New Rich—all those characters and situations which long ago passed across the great divide of willing suspension of disbelief to take firm root in Cliché Land.

What I like about McMurtry is that he sees those hypocrises, attritions, perversions, and absurdities common to the universal human condition and then isn’t afraid to admit, in print, that they exist even in Texas Our Texas. Not all “Texas writers” are entirely bold in telling truths on the home-folks, a condition reflecting our Boosterism Heritage, traditional Yahoo-ism, and dogged, unnatural institutional and family pressures to conform: to put a good face on all things Texas and Texan and to unite against critics from within or without. Introspection has never been highly prized in the land of my birth, or hard looks at why we operate as we do or feel as we feel. For too many years writing was considered “woman’s work” by most Texans and still is by some.

Our writing antecedents, including the revered J. Frank Dobie, too often hurrahed or gung-hoed and looked away from painful truths. Younger “Texas writers” are more honest than their elders. McMurtry, now a doddering 38, got in the truth-telling business early: Leaving Cheyenne was written at a precocious 23. He knows more truths now than he knew then, and has recently said of the book that it often seems to him the gropings of a somewhat dreamy very young man. Still: it’s a fine job; it rings true in the basics.

Not that I never quarrel with McMurtry. He sometimes harbors a touch too much romanticism, especially in his early work. His women strike me as a bit much, too heroic and long-suffering and strong. Too good. He sees ’em tough, but seldom does he see ’em mean. And Texas probably has as many mean, bitchy, neurotic women as any place on earth, with the possible exception of Manhattan; there, of course, they’ve gathered from all points of the compass, while our own crop is largely homegrown. McMurtry recognizes their ability to fight back, to survive in tough country, and knows that Texas women may often be stronger than their men. But I think he misses the extent to which large numbers purely enjoy wrecking and plundering and flashing their stingers.

And in The Last Picture Show, it’s my feeling that McMurtry too gently judges what a small town would tolerate should word get around that a high school kid was regularly diddling the coach’s wife—especially in the 1950s. There are just too many busy bodies and bored avengers to permit anything short of catastrophe in retribution. I believe one—or several—bad things would have happened: the coach would have been fired, his wife would have been chased out of town, and the cuckolded would have killed (1) the student and/or (2) the wife.

But no matter. McMurtry writes of Texas and Texans as well, or better, than anyone and with a rare honest bite. If I green with envy at the thought of a fellow-author’s Texas book, it’s McMurtry’s In a Narrow Grave: Essays on Texas. That high standard will last awhile. So he is a favorite with me, and I am saddened and angry when—as in Lovin’ Molly—I find him foully used. Let us fade, now, into the recent past—back to Austin and Bastrop, in November and December, 1972—to discover how professional film folks could have so botched and perverted McMurtry’s Texas.

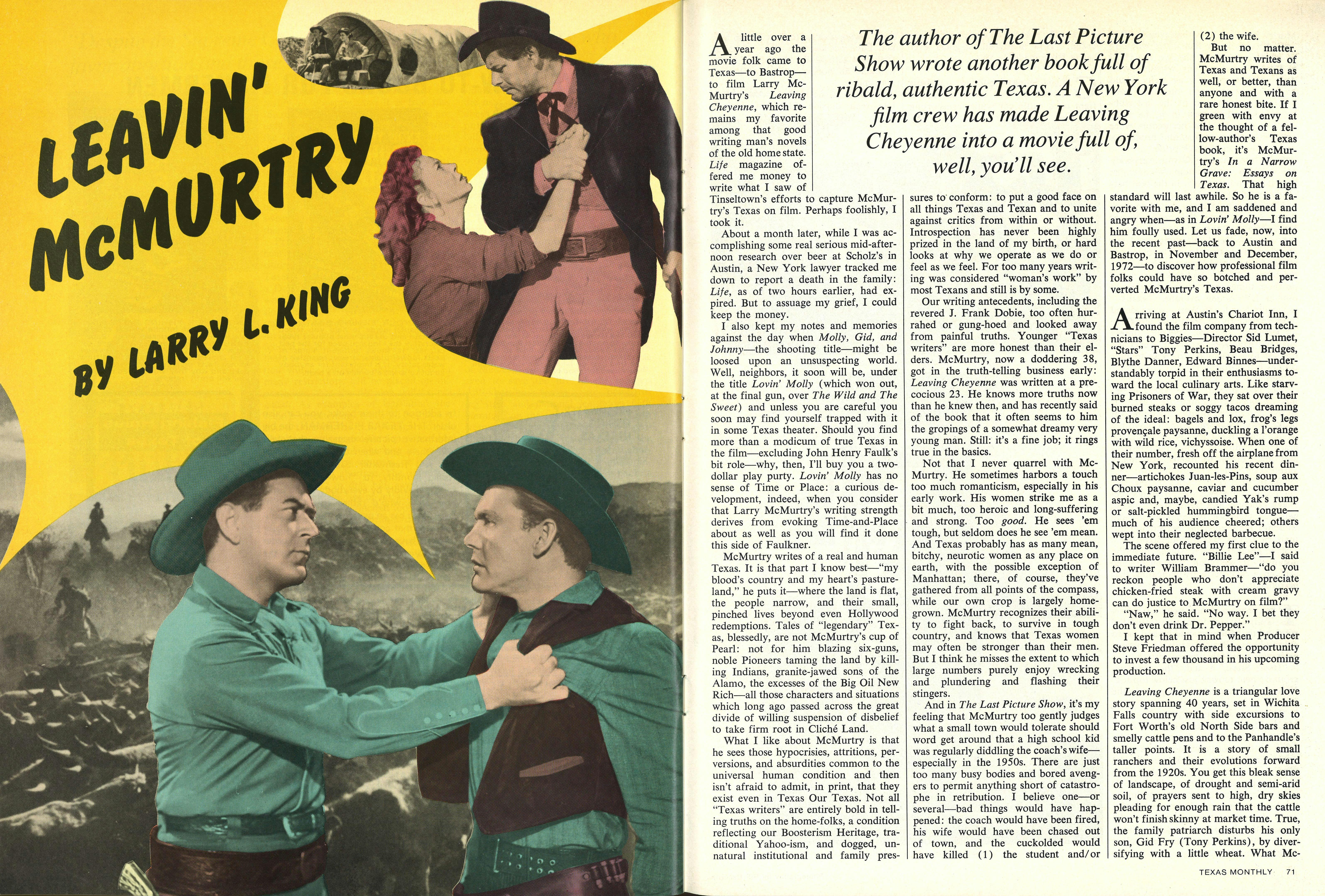

Arriving at Austin’s Chariot Inn, I found the film company from technicians to Biggies—Director Sid Lumet, “Stars” Tony Perkins, Beau Bridges, Blythe Danner, Edward Binnes—understandably torpid in their enthusiasms toward the local culinary arts. Like starving Prisoners of War, they sat over their burned steaks or soggy tacos dreaming of the ideal: bagels and lox, frog’s legs provençale paysanne, duckling a l’orange with wild rice, vichyssoise. When one of their number, fresh off the airplane from New York, recounted his recent dinner—artichoke Juan-les-Pins, soup aux Choux paysanne, caviar and cucumber aspic and, maybe, candied Yak’s rump or salt-pickled hummingbird tongue—much of his audience cheered; others wept into their neglected barbeque.

The scene offered my first clue to the immediate future. “Billie Lee”—I said to writer William Brammer—“do you reckon people who don’t appreciate chicken-fried steak with cream gravy can do justice to McMurtry on film?”

“Naw,” he said. “No way. I bet they don’t even drink Dr. Pepper.”

I kept that in mind when Producer Steve Friedman offered the opportunity to invest a few thousand in his upcoming production.

Leaving Cheyenne is a triangular love story spanning 40 years, set in Wichita Falls country with side excursions to Fort Worth’s old North Side bars and smelly cattle pens and to the Panhandle’s taller points. It is a story of small ranchers and their evolutions forward from the 1920s. You get this bleak sense of landscape, of drought and semi-arid soil, of prayers sent to high, dry skies pleading for enough rain that the cattle won’t finish skinny at market time. True, the family patriarch disturbs his only son, Gid Fry (Tony Perkins), by diversifying a little wheat. What McMurtry is telling us is that even in 1925 some Texans knew that cattle wouldn’t make it forever, that the last Big Herd had passed, that one day irrigated farming and perhaps even oil wells would come. But he obviously intended a yarn of cattle country and of the last stubborn independent men in it; he well-clued the reader that his people wore coiled hats, boots, jeans, and retained a certain fierce saddleback pride.

So director Sid Lumet trots everybody out in clod-hoppers and bib-overalls; they plant and reap as if in the best bottomlands of the rich Mississippi Delta.

First day on location I said to Producer-Screen Writer Friedman: “Jesus, Steve, what’s all this sowing-and-reaping shit about?” He didn’t understand the question. I said, “Look, you’ve got scenes bustin’ wild broncs, shippin’ cattle, birthin’ calves. And folks just didn’t do those things, back then, while rigged out in Li’l Abner overalls. Texans—especially North and West—surrendered most reluctantly to the plow. Up there in cowboy country, people simply wouldn’t have gone around 50 years ago dressed like Arkies on the way to pick prunes in California.”

“So?”

“So, goddamn it, there was a beginning shame to farming up there. It wasn’t considered quite… manly. It broke with tradition. And if anything would make them uneasy, it would by cracking tradition. They would have—and did—cling to their cattleman’s garb.”

“Yeah?”

“Yeah! See Steve, the difference between ranching and farming is . . . well, hell . . . between riding, I guess, and walking. Between being served by animals or serving them. Understand?”

The producer-writer stared into the distance. “I see what you mean,” he said, in a way perfectly indicating that he did not.

They had a fence-mending scene. Tony Perkins held a post atop the good earth while his buddy and hired man Johnny (Beau Bridges) whomped on it with a sledgehammer.

“Jesus, Steve,” I said, “the goddamn ground’s near to rock just below top soil. You couldn’t hammer fence posts in the ground!”

“How would you do it, then?”

“You’d use post-hole diggers! You’d have to dig deep, and you’d feel the shock all through your body. And when you’d finished your back would ache like you’d been kidney punched. But you’d know the fence would hold. It would turn back a stud horse trying to reach a mare in heat. Christ, even if you could hammer a fence post in the ground, the damn thing would collapse the minute you strung wire and pulled it tight.”

“So who’s gonna know,” Friedman asked. “how many movie-goers ever saw a fence made?”

Gid and Johnny—buddies, and rivals for Molly’s bed and love—had a fight on a cattle car while transporting their lowing charges to Fort Worth market. Each accused the other of having first slept with Molly and then of failing to make an honest woman of her via matrimony.

It was the sissiest, most awkward fight I’ve seen outside Elaine’s—which is where New York’s high-rent literati gather to juice, back-bite, screech and scratch out their professional frustrations or petty jealousies.

I sought out Director Lumet: “Jesus, Sid, that fight scene’s a real pussy-cat. It just won’t do.”

Lumet chuckled: “That’s my point. We’re getting away from the obligatory standard Texas machismo.”

“You’re wrong,” I said. “See, back then, two guys fighting over the honor of their mutual girl friend would be as mean and unreasoning as rattlesnakes. They’d literally beat shit and blood out of each other.”

“But these guys are good friends,” Lumet said.

“Beg your pardon, Sid, but that’s why it’d be so fierce. The only way it’d be worse is if they were brothers. In which case somebody might be seriously maimed.”

“We’re trying to reject the old myths,” Lumet said.

I said, “Look, I appreciate that. I’m sick of tough, tall Texans myself. And I feel about half-foolish insisting on blood. But given the emotional circumstances, I think blood would flow.”

The director smiled and touched my arm, forgiving my standard Texas parochialism. He moved away before I could say that the most damage I ever inflicted, or had inflicted, came in fistfights with a good friend or two. Except the time when I was 15, and had a bloody knock-down with my father.

Over drinks that night I tried to persuade Friedman. “It’s funnier Sid’s way,” he said.

“Maybe so, baby. But it ain’t real.”

One finally grew weary of approaching the film folk with unsolicited advice. Also, it got more difficult to slip up on their blind sides. When they spotted that certain outraged gleam or heard the beginning echos of “Jesus, Steve” or “Jesus, Sid,” they moved with all deliberate speed to safer quarters. Lumet reached the point of fleeing the Chariot Inn bar should he discover me in it.

At great expense to my soul I said nothing when a 1945 scene presented a Rural Route mail carrier not in khakis or tattered blue jeans but in a sparkling, tailored U.S. Mail costume which even Houston’s city letter-carriers would not adopt until years later.

I held my tongue when Gid and Johnny abandoned the Fry place to briefly cowboy in “the Panhandle”—maybe five minutes worth on film—where they were constantly in the company of lush Delta growths, lakes, and rivers.

I stood silently when Molly, accepting a telegram telling her of her son’s death in World War II, expressed her grief in front of a pastel-hued building which no Texas town had that early. Nor did I complain that she supported herself by clutching a huge, modern red-and-white stop sign even though stop signs in them days, pardner, were teensie-tiny and announced themselves in blacks and yellows.

I said not a word when Mr. Fry, son Gid, and buddy Johnny sat on horses near a cattle-loading chute—outside the corral—to chat of their market worth while, apparently, the cattle accommodatingly loaded themselves.

Watching the filming and the daily rushes, one knew the final product would offer no sense of place: that geography, somehow, was being judged unworthy of attention. Throughout Lovin’ Molly people canter by horse, wagon, buggy, or pickup-truck to this ranch or that farm or another town, without any sense of direction. You don’t know if a given trip implies a journey of a hundred yards or an equal number of miles: all you know is that wherever people go-whether to Fort Worth or to the Panhandle or to an adjoining spread-the landscape is as unvarying as the moon’s. Though it all looks as if it might yield 40 bales to the acre.

I grin and am warmed by recollecting an Early-Dewline warning flashed by Amarillo’s Buck Ramsey. Ole Buck for years was the quintessential Texas cowboy; he rode for wages, fought in bars, and his neck was red. Some years ago Buck Ramsey’s horse tricked him off, stomped him, and dragged him far enough that Buck has since been assigned a wheelchair. This cut down on Buck’s riding and fighting, though not on his drinking or sense of humor. As a side effect, Buck was caused to read and mull Camus, Dickens, Twain, McMurtry and better. So when I called Buck Ramsey one night to inform that Leaving Cheyenne would soon be filmed near Austin, Buck gave the perfect literary criticism: “Shit, when will them folks learn not to film cowboy stories down yonder in that damn swamp country?”

Stars, producer, and director jangled in anticipation of Larry McMurtry’s heralded visit to the shooting location. He disappointed them by arriving in Austin after the day’s wrap. Though McMurtry had—and has—no responsibility for the flick, other than having sold its screen rights, Lumet and Friedman sought him out for dinner and to court his good will. McMurtry, who does not flower in the presence of excessive praise, squirmed and wouldn’t look anybody in the face while being told of what a grand, perfect “vehicle” he had provided.

“You know what your book’s about?” Lumet curiously asked.

Startled, McMurtry said something sounding like er-ah-whonk-oh.

Lumet leaned in, grasping McMurtry’s arm, frowning to show Deep Artistic Insight: “Larry, it’s about…well, it’s about…the glory of no reward!”

“Hmmmmmmmmm,” McMurtry perfectly responded, failing to look up from his cucumber salad.

Later, McMurtry witnessed the latest daily rushes flown down from New York processings: rough cuts and retakes of scenes put on celluloid three, four days earlier. Often he snorted or muttered to himself.

By now they were filming some scenes from the 1960s portion of the book, when the principals have aged 40 years over the film’s beginning. Tony Perkins, who in the opening reel appeared much too used and scabby for the 23-year-old he portrayed, now appeared to be about two years older than Christianity: possibly the worst make-up job since Nixon’s in that first debate against Kennedy; he spoke in a voice cracking near to a yodel, and exaggerated the shakings of terminal palsy. In the darkness of the Chariot Inn’s make-shift screening room, generally a meeting place of Lions and Rotarians, McMurtry took one look and grunted like somebody had poked his ribs with a pitchfork.

He suffered the sissy mock fistfight, Blythe Danner’s pitiful attempts at a West Texas accent (it sounded as if it had been shipped in from Philadelphia by way of Pascagoula), and a 1925 scene where Gid and Molly, semi-sensually roistering in an open field, groped in passion near a fresh cow-plop obviously and recently tracked by a 1972 giant-type tri-wheeler. When a scene depicting “the Panhandle” revealed green foliage, and many running brooks, McMurtry breathed: “Is that Vietnam, or Missouri?”

McMurtry talked near to dawn in a motel room with old Texas friends, instructing how, for all their millions, movie folk seemed to possess natural talents for being unable to distinguish asses from elbows. He philosophized that, well, hell, you wrote something and then you moved on to write something else and the devil take the hindmost.

As a perfect counterpoint to the Technicolor turkey then in the making, he reported on his old cattleman daddy, who—aged, ill, long past any hopes of Big Herds—had freshly battled a mad cow to at least a moral victory though suffering a bootful of blood and a major fracture. It was a symbolic story, almost as poignant as the old yarn of the dying Indian tribe buying a Longhorn steer and then killing it the way they—and their ancestors—had once killed countless buffalo. And I thought it an affirmation of that which McMurtry writes about: life’s natural attritions, and inevitable change, and the stubborn surrenderings they force. You knew damn well that tough old Jeff McMurtry hadn’t worn bib-overalls—or given a thought one way or another to Texas machismo—in playing out one of the final, natural dramas of a hard-scrabble ranch life.

One night on location outside Bastrop, as a few dozen of us shivered in a chill wind and klieg lights, I cornered a big, cheerful, robust native-Texan rancher who supplied cattle and horses for Lovin’ Molly and also was being paid as a technical advisor. True, he had taught the principle actors how to mount horses without appearing totally foolish or getting hurt, how to toss a rope or to saddle-up and other “techniques” that were to him second nature, but how-I asked-could he permit the make-believe cowboys to miss or misinterpret so much, to commit so many dozens of small boo-boos he certainly must have recognized?

He was a good ole boy, not without a certain country ambition, and we’d poured enough booze together that I knew he owned more smarts than he’s publicly revealed. He lowered his voice and carefully checked for outsiders: “Listen,” he said, “them people payin’ me $3600 for six weeks a-work. And I got three buttons to educate. This is the best and quickest money I ever seen. Maybe, you know, them people may come back down here from New York to make another picture one day. You want me to screw up easy money by quarrelin’ with ‘em now? Whatever pleases them people, cousin, just tickles me plumb to death…”

All prevailing deceptions were not hatched by Texans. Governor Preston Smith and several state legislators “starred” in a cattle auction scene ending with the auctioneer crying out, “Sold for forty dollars to Preston Smith.” I remarked to Producer Friedman that the scene didn’t appear all that vital to moving his story line. He grinned: “Well, it never hurts to politick with the politicians. Meanwhile, when we need cooperation from the authorities—well, this scene hasn’t hurt us.”

I said, “And there’s always the cutting room floor. You can always decide during the final editing that maybe Governor Smith’s scene is expendable.”

Friedman laughed: “You’re pretty damn smart for a Texan. You sure there’s not a little New York hustler somewhere in your bloodline?”

P.S.: If Preston Smith made the movie as released, I neither saw him nor heard his name.

Beau Bridges, cast as the happy-go-lucky Johnny, noted that many real-life cowboys chewed tobacco. Concluding that perhaps Johnny would take a chaw, too, he wrote that bit into his part. “A guy passed me some of this stuff that looked like a pressed rag,” he said, “and I chewed it and nearly passed out.” By now Director Lumet loved the tobacco-chawin’ idea, and Bridges was stuck with it. He tried substitutes: licorice, black bubble gum; nothing seemed to work but the real thing. Beau spent a lot of off-camera time rinsing out his mouth, and gagging.

The cast and crew grumbled of a Spartan social life. One night a party was arranged in the home of a congenial Austin man who supplied booze, music, deposits of minor dope, and friendly girls attracted to the possibility of meeting Tony Perkins. It was the flop of Austin’s social season: only the technicians among the film folk appeared, and after nervous introductory drinks and chatter they segregated themselves to talk of Joe Namath, cream cheese, the New York Giants, and how wonderful it would be to see the spires of Manhattan.

Since Producer Friedman had made much—in press conferences and local speeches—of how at home New Yorkers were being made to feel in Texas, I asked one of the crewmen-by then drunk-what he really thought of the cowboy life and the region. “I get enough of these salt-of-the-earth types in a hurry,” he said. “Hell, they don’t even know what stick-ball is!”

Finally, it was over. At the cast party—attended, again, only by technicians and, this time, Beau Bridges from among the “stars”—there were mutters that anti-Semitism had been felt in Bastrop. How so? “Well,” said an assistant producer, “when we needed to lease farms or ranchers or equipment for certain scenes, people tried to hold us up. And one rancher said to me, ‘Listen, you New York Jews come in here and git rich makin’ fun of us and try to get out for six-bits.’ I can’t say I won’t be happy to get home.”

I saw McMurtry last summer, shortly after he’d witnessed the first rough-cut screening of Lovin’ Molly; he was in a state of mild shock.

“It’s simply dreadful,” he said. “Tony Perkins plays a swishy boy until the final reel, and then suddenly he’s older than rocks or water. The old-age make-up on everybody is simply grotesque. There’s no sense of direction: Lumet apparently shot the thing in track shoes—zip, zip, zip. People at the screening kept laughing in all the wrong places, and some walked out. Near the interminable end, I realized a woman behind me had been crying for 20 minutes. I wondered what kind of a woman would cry at such a film. When I risked a look behind me, it was my agent.”

With some 20 minutes clipped from the original cut-mercifully, most of it in the mismanaged “old age” sequences—Columbia Pictures held a recent New York screening.

I was surprised to find Larry McMurtry sitting alone near the front row. “Glad to see you,” he said. “I’ll probably need your moral support.”

What in the hell was he doing there?

“Well, I’ve been asked to write a review for The New York Times.” We laughed for the only time that day.

The longer the film ran, the lower McMurtry sank in his seat: “It’s not so bad if you only see the top half of the screen.” We suffered it all again: sowings and reapings, technical boo-boos, lush growths and rivers allegedly indigenous to Panhandle country; Blythe Danner clasping a bloody, wet, newborn calf to her generous bosoms and then—yes!—kissing it. McMurtry covered his face with his hands; his shoulders shook. I don’t know if he was giggling or crying. We felt no sense of how hard-scrabble ranch life might be on the high Texas plains; received no notions of sandstorms, summer parchings, winter freezes, wild lonesome winds, or incessant jangling country tunes.

We escaped to a bar, drinking silently and shaking our heads.

I asked McMurtry what he intended to call his review for The New York Times. He perked up and smiled for the first time in two hours. “I’m gonna call it,” he said, “‘Leavin’ Lumet.’”

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Longreads

- Larry McMurtry

- Bastrop