I can’t escape Leon Bridges. He’s been playing almost everywhere I go: in the salon I visit for a post-vax manicure; at JuiceLand as I wait to overpay for my smoothie. Somebody’s painted his Texas Sun cover art on a brick wall near my local Target, in Austin. It’s been this way since last summer, since Leon Bridges first forced his way into my life. I’d been asked to write this story and said no. (Fear of commitment and failure more than anything.) I headed to New York City, sure of my decision, free of all responsibility. Free of Leon Bridges. Then, somewhere on the Jersey Turnpike, I ran out of tunes. I opened my Spotify “Discover Weekly” playlist. Shuffle, let it play. A few songs in, I heard these beautiful chords, real simple, kinda old-school church, kinda old-school rock and roll, real soft. Ooh, this is good. I turned it up.

Your love poured into my heaaaarrrrtt, a man crooned.

His voice cut through everything, through the chords, through my rental car speakers, through me. It was Leon Bridges. I had to know what kind of man could sing a song like that.

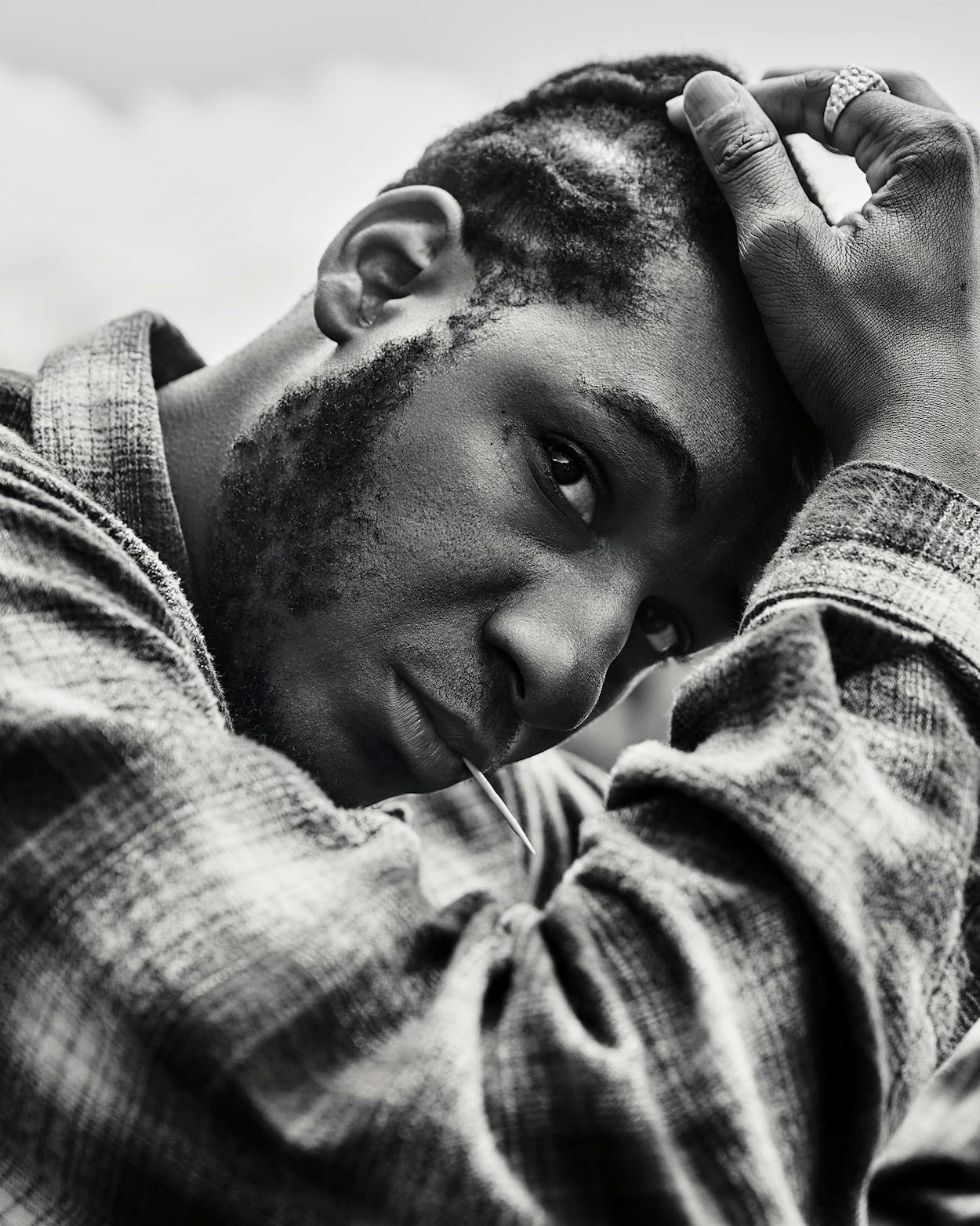

I’ll tell you a few things up front about that man, now that I’ve met him for real. He’s taller than I thought. He’s funnier than I thought, cackles with his whole body, lifts his eyebrows as he laughs, like he’s surprised that you said something funny. He’s Blacker than I thought, and if you know what I mean, then you know what I mean. He really does dress that way, even in the grocery store. He really will, as the musician-prophet Terrace Martin warned me, answer a question with a guitar and a song. He really is that nigga. (For anyone who’s lost, let’s just say he is the man. Okay?)

We were in Los Angeles one crisp, half-sunny afternoon this spring, standing in an alleyway on the sketchy east end of Santa Monica Boulevard before heading into Gold-Diggers, the studio-bar-hotel where he lived and drank and recorded his third album, Gold-Diggers Sound, scheduled to drop July 23, ten days after his thirty-second birthday. Well, I was standing. Leon moved around, this way and that . . . foot against the wall . . . feet sliding over the pavement as he broke into a jig . . . hands on his hips, hands over his face, staring at the ground, gazing at the sun. He didn’t fidget. He moved like a man trying to find good cellular reception for his own mind. Later, inside the studio, with his guitar, he was still. “Guitar is the only thing that makes sense,” he said at some point. Later, we said together, “Leon Bridges is that nigga.” I didn’t think he’d say it, accustomed as he is to playing humble (he really is humble), to taking himself down a notch so others won’t do it for him. He didn’t think the magazine would let us print it. Neither did I. Part of me wondered whether he hoped the magazine would scrap the whole story, if every magazine would scrap every story about Leon Bridges. Because, although I can’t escape him, Leon Bridges would love few things more than to escape me, to escape you and all the rest. He has his reasons, which we’ll get to, but most of all, he’s simply used to being alone.

That’s how this whole thing started.

The Long Walk

On a winter evening in 2013, a 24-year-old young man finishes his shift bussing tables at Rosa’s Café, on the suburban southwest edge of Fort Worth. He’s had this gig for seven years, kept it while he studied at Tarrant County College, and after he dropped out, in 2010, to help his mother pay the bills. At TCC, he dreamed of being a dancer, a choreographer. His biggest dream at present is leaving Rosa’s forever. He’s leaving now just for the night. It’s New Year’s Eve.

One thing he learned at TCC was how to play guitar. A classmate named Kyree let him borrow hers one day, taught him a few chords, nothing fancy. He’d been secretly writing songs for a while by then, and the songs were nothing fancy either. Nothing vulgar, nothing sexual, nothing worldly. At eighteen, the young man had given his life to Christ. Joined a Reformed church of his own choosing. He liked that the church’s music featured some piano, some percussion, a guitar, but “nothing crazy.” Liked that the songs were mostly hymns, instead of big productions. And he really liked Jesus. Took the Gospel seriously. So seriously that he threw away his favorite records when he got saved. Threw away Usher’s 8701, which his father bought him for Christmas back in 2004 (and which Leon hid from his devout mother). Threw away 112 and Jodeci and H-Town. There’s no good Christian R&B, he complains to himself. He’ll write his own . . . or try to. He finds beats on Bandcamp. Starts playing them in his mother’s Honda Accord on his way to Rosa’s. One day, some lyrics come to him. He pulls over to write them down.

Your love poured into my heart

Your love poured into my heart

Your love poured into my heart like the water that flows from the pitcher

Holy Spirit penetrated my stone

Heart like the nails that were driven through your skin

Growing up, Leon was so bashful that he really didn’t have any friends, just a few kids he kinda knew. When I eventually speak to one, who met Leon in eighth grade, the first thing he says is “He didn’t talk.” A few minutes later, he stresses, again, “I’m telling you, he didn’t talk to anybody.” But another thing Leon learned at TCC, thanks to a group of guys we’ll meet later, is that all “that shy shit is disrespectful” of the gift. At their urging, Leon began to take his music seriously, seriously enough to head to open mics, plug his iPod into a speaker, and sit before three people, four, ten, nobody, and sing his first song, “Conversion.”

Initially he called himself Lost Child. That’s what his mother, Lisa Sawyer, used to say whenever he was overdue for a haircut: “Boy, you looking like a lost child.” It was Lisa who led him to God. She’d found his Myspace page, seen the language he was using. “Something like ‘I’m that nigga,’ ” Leon tells me, falling away as he laughs. She sat him down and warned that he needed to get his life right. So he did. He threw away all his favorite tunes, wrote “Conversion” and others in their place. He believes in the songs enough to know he needs a better stage name. People have said he looks like the actor Leon (perhaps best known for playing David Ruffin in the 1998 Temptations miniseries), and “Leon Bridges” brings up much better Google results than his given name, Todd Bridges.

He still sees singing, if not the songs themselves, as a transgression—so much so that he hides his new life from his church friends and from his mother. And as he goes his lonely, “godforsaken” way, as he learns to play guitar and stops learning Scripture, he’ll write a song that will make him famous someday, though he can’t imagine that now. (He can’t even imagine leaving Rosa’s for good, now.) He got the idea for the song after seeing one of his favorite groups, the Dallas-based Texas Gentlemen, who infused their country sound with funk and blues. Came home from that show and posted on his Facebook, “I’m gonna write a river song.” When the song comes, he’s in Crowley, which is fifteen miles south of Fort Worth, at his mother’s house, which will one day belong to someone who plants a Trump flag out front. He’s in the garage because that’s where his room is. His mother has no idea he’s writing a song in there, doesn’t even know he can sing. None of his people know he can sing.

Well, there was this one time, when he was about six, when he got caught. The Lion King had just come out on video, and little Todd was watching along with his father, Wallace. Wallace left the room for a moment and returned to find his son belting so hard, so well, he assumed at first it was the movie soundtrack. He’s stunned, runs to tell Todd’s mother, gathers folks around the next time they have company. Listen to my son sing, he urges them. But Todd won’t sing a word. Won’t open his mouth, he’s so shy.

Years later, when he writes his river song, he’s eager for someone, anyone, to listen. And since he’ll come to see himself in the lineage of Fort Worth boys like Townes Van Zandt, he’ll feel, deep down, that his river song is a folk song, that he is a folk singer. Perhaps this much is clear to him by New Year’s Eve 2013. Only a folk singer or a madman, if there’s a difference, would do what he’s about to do.

He’s got a gig on this night, an open mic at Pop’s Safari Cigars, but he doesn’t have his mother’s car, and his coworker refuses to give him a ride. It’s 7.5 miles from Rosa’s to the cigar shop. That’s roughly two hours on foot. If you’re Todd Bridges, it might be longer because you’re carrying your guitar, which you’ve stored in your manager’s office all day. And it’s cold as hell. And your sneakers with the no-slip soles don’t have much arch support. But you want to sing your songs, so you take off walking.

As the musician and producer Josh Block, a guy he’ll later meet, describes Leon’s probable path, he’s “walking from a Black neighborhood, to a pretty middle-class white neighborhood, through a rich white neighborhood, into a Mexican neighborhood, back into a rich white neighborhood, probably through another predominantly Black neighborhood, Como.” I’m from Dallas, so truly couldn’t care less about Fort Worth neighborhoods, but I’ve walked enough to know that two hours is a long-ass walk, and 45 degrees is pretty cold for a Texan (or at least for me). By the time Leon gets to the cigar shop, his hands are so numb that he can hardly strum his guitar. But he strums as best he can, and he sings.

The Deal

By the following New Year’s Eve, Leon Bridges had signed a contract with Columbia Records, home of icons like Beyoncé and Bob Dylan. If that seems like it came out of nowhere . . . how do you think Leon felt?

“I was scared as f—.”

That’s Leon talking about his December 2014 meeting with Columbia. We’re in one of those big black SUVs that always feel silly when there are only a few people inside, en route to dinner after a long day at Gold-Diggers. With us is Sarah Mary Cunningham, one of the few publicists I’ve ever met who makes you respect the world of publicity. She remembers everything and everyone, and she launches into a warp-speed history of how the meeting came to be.

“Justin Eshak [a Columbia executive] came into my office, which was rare, and he says, ‘Come into my office; I need to play you something.’ So I went in, and he’s like, ‘This is this kid from Texas. His name is Leon Bridges.’ And I remember just standing at his desk, and he played me just the two tracks that were on [the music blog] Gorilla vs. Bear. He’s like, ‘This kid is completely self-trained,’ blah blah blah. And I remember, Leon’s voice filled his room, and Justin had a really sick stereo in that room. And I remember thinking Leon’s voice was just so warm and pure and really beautiful. So I say, ‘Can I have those tracks?’ So Justin emailed them to me. My office had these window seats. It was snowing, and I sat in the window seat and hit repeat, and I just played those two songs and vibed out. Then my friend Meko Yohannes, who at the time worked for Snoop Dogg, was in New York and happened to be meeting me that night for dinner. And I was like, ‘I don’t think I’m allowed to play this for you, but I need you to listen to this kid.’ So I dragged Meko over to Justin’s office, and he played the song, and Meko was like, ‘Oh my God. This is my heart.’ ”

Such awestruck responses were the engine that propelled Leon from hoofing it across Fort Worth on New Year’s Eve 2013 to sparking a bidding war among the country’s major record labels a year later. Austin Jenkins, then the guitarist for Texas psych-rock band White Denim, was one of the first to fall for Leon. Jenkins’s girlfriend introduced the two of them at a bar because she saw Leon’s high-waisted vintage Wranglers, just like the ones her boyfriend loved. A couple evenings later, Jenkins heard Leon sing at an open mic and figured he was singing covers, the songs were that good. Jenkins pitched Leon on joining him and White Denim’s drummer, Josh Block, in the studio to record. Block remembers Jenkins showing him a photo of Leon at the Stockyards. “I was like, He’s in the Stockyards? That’s badass.” Leon later explained why his presence might have surprised people: “The Stockyards is predominately a white hangout. It’s a lot of cowboys, that type of stuff. There was a spot called Pearls, a honky-tonk type of place. I remember going there a handful of times, and it was uncomfortable for me, being the only Black dude in this area.” Why’d he go? “I just always loved the Stockyards aesthetic.”

Leon says this word a lot, aesthetic. It’s part of his gospel: how a thing looks will dictate whether he can vibe with it, tolerate it at all. Block and Jenkins shared Leon’s aesthetic-sonic tyranny—the tape machine in their studio once belonged to Dan Healy, the longtime Grateful Dead audio engineer—which is one of the main reasons Leon agreed to meet the two at Shipping & Receiving, a Fort Worth warehouse that had been turned into a mixed-use complex, for a four-day test session.

By then Leon had written a song that scared him, a song called “Coming Home.” His first steps into music had already caused spiritual angst, and now there was this tune that opened with Baby, baby, babe. As in a girl, not Baby Jesus. He was too far gone, though. “I felt like I’m just gonna do what the hell I want to do, write what I want to write about. I know my friends might not accept it. My mother might not accept it. But this is what I’m passionate about.” It’s important to note that Leon’s mother has been his champion the whole way; we often overestimate our mothers’ condemnation and underestimate their love.

So, “Coming Home” became the first song they recorded at Shipping & Receiving. It was one of the songs Jenkins and Block sent to Jonathan Eshak of Mick Management, who represented White Denim at the time. It was one of the songs Eshak sent to the blog Gorilla vs. Bear. “Coming Home” then went viral on SoundCloud. Later, Eshak sent the songs to his twin brother, Justin, who just happened to be an exec at Columbia Records. Justin sent it to Sarah Mary Cunningham, who played it for her friend Meko, who responded, “Oh my God.” Columbia wanted a meeting.

Back in the too-big SUV, Sarah reminds Leon of the day they met.

“It was bitterly cold out, snow on the ground, gray New York nastiness. I came into the room, and you had your hands like this”—Sarah rubs her palms on her knees—“and now I know that’s a nervous gesture.” They both laugh. “You did not say a whole lot, but I loved your outfit. We chatted, and I was like, ‘I swear to God, if this kid goes to f—ing Atlantic Records—’ ”

“Man, in no way would I have,” Leon butts in. He went with Columbia because they wanted the songs as is, instead of the more polished versions other labels hoped he’d remake before releasing his debut album. “ ‘River’ was essentially a demo. And Columbia’s like, ‘No, we want that version on the album.’ ” Hearing this, I pull up Spotify on my phone and play Aretha’s “Respect” for Leon. I point out the part when Aretha’s voice cracks—what you neeeEEEd—because she recorded the song while fighting a cold. “Ohh, see,” he claps. “That’s the thing. The imperfections in it humanize the person.”

Signing with Columbia wasn’t just about that, though. Leon signed with Columbia because, in the words of Block, “they gave him a nineties deal.” What’s that? He laughs. “A deal we haven’t seen since the nineties.”

Leon signed his big record deal at a Staples in Fort Worth. Up till then, he’d been making $8.75 an hour washing dishes. When the Columbia direct deposit hit, the first major thing he did was pay off his mother’s house. Rightfully so. After hearing of his long walk, she’d helped him buy a Ford Fusion. She’d made it possible for him to get here, even if she never thought he’d get here, if only because, as she later told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, “he always avoided anything that would put him in the public’s eye.”

So much for that.

Bottle Rocket

Coming Home debuted at number six on the Billboard 200. Four months later, in November 2015, Leon was invited to the Library of Congress to pay tribute to one of his heroes, Willie Nelson. Sarah reminds Leon of that night. “Willie was so happy to see you, and I remember he’s like, ‘Leon, remind me, are you on a major label?’ And you were like, ‘Yeah, I’m on Columbia.’ And he goes, ‘Oh, yeah, Bobby’s been on that label his whole life.’ He was talking about Bob freaking Dylan. And he’s like, ‘And have you met Rosie yet? Her daddy was on Columbia.’ And he points over at Rosanne Cash.”

Paul Simon was there for Leon’s Willie tribute and rushed over to say, “You’re just amazing.” How can the self-proclaimed “most bashful, introverted person” pull off a set like that? Or perform on Saturday Night Live, as Leon did in December 2015? “It’s a different persona I tap into. Like, almost facing your fears. Every night. But when I’m in my element, I can just lock in and say, Okay, I want this experience to be seared in their memory. I gotta kill it. Even when I’m nervous, like when I performed at the White House.”

That came next, in February 2016, at a tribute to Ray Charles. Leon wore one of Ray’s old jackets, a big gold number loaned to him by the musician’s foundation. He sang “Lonely Avenue.” One way he seemed to stay in his element was to never, ever look Barack and Michelle Obama in the eye. It’s hilarious to watch, which you can do on the internet. He finishes the song and finally turns to the First Couple. He bows, Thank you, Mr. President, and they beam at him. (The president is such a fan that he invites Leon back for his fifty-fifth birthday party, where “shy” Leon has a dance-off with, among others, Stephen Colbert.)

That same month, he’s in Los Angeles for the Grammys. Coming Home had been nominated for best R&B album but loses to Black Messiah, D’Angelo’s comeback record. I’m probably reading too much into this, but there’s a slight chance I’m not, and so I’ll tell you what I think: I think this is some kind of cosmic sign.

In 1995 D’Angelo released his debut album, Brown Sugar, which announced him as perhaps the most gifted of the new crop of male singers that would eventually be labeled as neo-soul. The music is smooth, throwback. The album goes platinum. Then D’Angelo goes underground. A few years pass until he locks himself in Electric Lady studios with a crew of great musicians. They jam. Watch old Soul Train episodes. Then, to launch the album Voodoo, D’Angelo films the hottest music video in the history of the world, half naked, alone against a black screen, singing the lyrics to “Untitled (How Does It Feel).” The video becomes . . . I mean, I’m still processing it twenty years later, it was that hot. The only problem is that D’Angelo absolutely does not want to be a sex symbol. He’s a musician, a master of his craft, but he goes onstage and women throw their panties at him, scream, Take it off! He spirals, vanishes, almost dies in a car accident in 2005. It’s nearly a decade before he returns, fully clothed and clothed in his right mind. Another great album, another Grammy. But what a price he paid for that strange journey—a journey fueled, at least in part, by the paradox great artists often face: the thing that launches you can also lead you to a dead end.

Leon reached his dead end a few months after the Grammys, at the 2016 Roots Picnic, in Philadelphia. He’d been a festival darling since 2015, when he made a splash at South by Southwest, and had gone on to play some of the biggest fests, like Bonnaroo and Lollapalooza. They all seemed to love Leon. They also happened to be mostly white. Not so at the Roots Picnic.

“It was almost as if I was playing into a wall,” Leon tells me, still stunned by the cold reception he received. He’s not lying; you can see clips on Instagram. In one, a young Black woman sways absentmindedly as she scrolls on her phone. Everybody else stands still like they’re in line at the DMV—except for one tall white guy, who raises his fist and jams hard. To be fair, Leon had the misfortune of playing right after the late DMX, whose high-energy show should arguably never be followed by anyone, especially not a soul singer. Leon was also new to many in the audience (his management later confessed to knowing best “how to market to white hipsters”).

In Philly, Leon learned a lesson that I’m sure he’d learned as a kid but had not learned, perhaps, as a recording artist: Black people are the toughest crowd in the world. (Remember: A young Ms. Lauryn Hill was booed at the Apollo. Outkast was booed at the Source Awards.) Even tougher if you happen to show up with a white band, dressed as if you never got the memo that the sixties died, with a spare, retro sound resolutely out of step with the heavily synthesized R&B and trap-style hip-hop that dominated the landscape. (Ironically, the star trap trio Migos influenced the way Leon sang “River.”) That is not to say Leon was universally rejected by Black listeners. There were many ardent Black fans like my cousin who, way back in 2014, urged me to watch a clip of Leon singing “Lisa Sawyer,” one of the standout songs from Coming Home. But when you’re sensitive, as Leon is, and you’ve received so much love, as he has, a boo (or silence) might feel like a death blow.

“Nigga, I wanted to cry,” Leon says of that day, which he and his team considered a wake-up call. As he started to look toward his follow-up to Coming Home, he felt that “we exhausted what we could do with that aesthetic.” He needed a change. “Part of my thought process was, I’m not going to be fulfilling your wet dreams of having a soul revivalist man. I’m way more than this.” He wasn’t sure what, if any, wet dreams he would fulfill, but he knew he wanted to keep his sonic foundation soulful. And he knew what question he had to answer: “How do I connect with my people . . . more?”

Jonathan Eshak puts it this way: “He was a bottle rocket. But what we realized pretty quickly is that [the album] went niche massive. That was naiveté on [the part of management] too. We thought if we just play a WBLS radio event and play the Apollo, then all of a sudden Black audiences are gonna care. We learned quickly it doesn’t work that way. We had to start at the bottom.”

Going Hollywood

In 2015 the MacArthur “Genius” grant winner Dave Hickey, who grew up in Fort Worth, wrote a blistering article in this magazine entitled “Don’t Move to Texas” that included this pungent line: “All my favorite Texans had to leave Texas before they could blossom like the little flowers they were: Ornette Coleman, Bob Rauschenberg, Candy Clark, Waylon Jennings, Don Barthelme, Bobby Keys, Rip Torn, and most egregiously, Natalie Maines.”

That made me think of Leon, who likewise left Texas and headed to Los Angeles to explore a new vision for his second album, Good Thing. I called Hickey because I wanted to be sure I understood his theory. “It’s easy to find people that love you in Texas,” he explained from his Santa Fe home. “It’s hard to find people that hate you. Now, that seems like a normal thing. But really, the push-pull of criticism and response and crowds is pretty important. And Texas is a place that hates anything negative, you know what I mean?”

I thought I knew what he meant. But I had this big outlier to his theory, this big, ugly Houston Rodeo response to Leon Bridges in 2018, when Black Texans—not all, but enough—made clear that if they did not hate Leon Bridges as a man or an artist, they at least hated the idea of him performing on Black Heritage Day. They might have shared many of the same reservations held by that Roots Picnic crowd, but their objections were also uniquely Texan: Leon Bridges just wasn’t big enough. With all the famous Black artists out there, folks seemed to reason, why should our night go to someone we’ve got to google?

“When they announced it, niggas was lighting my Twitter up,” Leon remembers sadly.

“Who tf is Leon Bridges?!?” someone tweeted. “Rodeo Houston y’all played us on black history night.” Another added, “rodeo houston gave us leon bridges for black heritage day bc he’s black but attracts a white crowd. damn they showing they trump colors.”

Plenty of journalists, many of them white (and one of them from Texas Monthly), stoked indignation with their own takes. And the outrage went further, Leon recalls. “The most off-putting thing was when people were like, ‘Oh, I ain’t going, I ain’t going.’ Damn near about to boycott. That’s when it really got real.”

It got so real that Eshak sat down with Leon to discuss the possibility of calling off the whole thing. I ask Leon why he didn’t. “I didn’t wanna give them—” He stops, shifts in his seat. “In my mind, it was Let me just persevere . . . get up there, do what I need to do, and keep moving.”

I’ll say it for him: he didn’t wanna give them the satisfaction of knowing they’d bullied him into dropping out. Leon Bridges may be shy. He may love to chill in the cut, watch other people talk. He may have a laundry list of self-doubts. But remember: Leon Bridges is also a man who, on New Year’s Eve 2013, after working a long shift bussing tables, walked for miles in the cold just to strum his guitar and sing his songs before a handful of people. Remember: Leon Bridges is from Fort Worth, where the West begins, where Black cowboys roamed the Chisholm Trail. Leon Bridges is also from the south side, where his father ran the Bethlehem community center and is still respected by the toughest gang members in town. Remember: Leon Bridges is that nigga.

He was also facing the same dilemma Black artists have always faced in this country, the “undertow of sharp criticism and misunderstanding from his own group and unintentional bribes from the whites,” as Langston Hughes wrote in his 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” While that undertow might have shaken Leon, it has not, so far as I can tell, led him to grasp desperately for acceptance. As Eshak says, “Leon has embraced his singularness.” Just as Langston recommended nearly a century ago, “we build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves.”

So Leon played the Houston Rodeo and later, at the invitation of the popular local rapper DJ Mr. Rogers, went to a club. “The place he plays is straight hood,” Leon remembers. “The night I was there, this dude’s playing all the trap hits. In the middle of all that, he drops ‘River.’ And I was nervous. But I looked around, and heads was vibing with it. That was a moment I said, Okay . . . my people . . . they with me.”

A couple months later, Good Thing dropped, earning Leon another Grammy nomination for Best R&B Album, and his first win, for Best Traditional R&B Performance. He would likely agree, at least in part, with Rolling Stone’s view that “not everything works” on the album, but neither the acclaim nor the criticism mattered more than the strides Good Thing helped Leon take as a man and an artist. Under the guidance of Ricky Reed, who has produced hits for stars like Lizzo, Leon learned to write songs collaboratively, pushed his sound beyond retro soul, sang even more directly about sex. Los Angeles also affirmed his unique fashion sense and unleashed his love for nightlife (he didn’t drink or party while he was recording Coming Home).

Reed saw the Good Thing process as “the first step of Leon grabbing the reins of his career in a new way,” even though Leon knew this new direction might come with consequences. “I was really nervous about putting Good Thing out in the world,” he told me. “Just thinking What if I lose people? My second album could have f—ed my career up.” He felt the fear and did it anyway.

That same spirit led Leon to make another tough call the following year, when he pushed for the release of Texas Sun, a four-song EP on which he collaborated with the band Khruangbin. Leon was unfamiliar with the Houston trio before they opened for him on tour, where it became clear that Khruangbin’s galactic funk-soul-world music synced brilliantly with his own genre-fusing sensibilities. One night while they were touring together, Khruangbin bassist Laura Lee sent Leon an instrumental, to which he wrote a song called “Ghetto Honey Bee” before going onstage. Laura dug the song, as did management, so Leon went down to Houston for more sessions with the band. It was a career-shaping process for him, as he saw that he could partner with a wide array of artists (he’s since worked with musicians ranging from John Mayer to Diplo) as a way to whet his expansive musical appetite and reach new audiences.

There was only one problem with Texas Sun. “The label basically told everybody, ‘This is not coming out,’ ” Eshak recalls. The higher-ups at Columbia felt the songs weren’t radio-friendly enough, weren’t pop enough. “We were defeated,” Eshak continues. “Then, Leon’s like, ‘Nah, man, it’s coming out . . .’ and we’re like”—Eshak slams the table with excitement—“ ‘F— yeah, it’s coming out!’ ”

Leon After Dark

Among all the badass musicians who came together for Leon’s third album, Gold-Diggers Sound, one stands out as powerful evidence of Leon’s revelation in that Houston nightclub. Terrace Martin is his name. Martin was raised amidst the L.A. gang wars of the eighties and nineties. He picked up a saxophone as a high school freshman and was so cold on that horn by sixteen that he started playing with Fort Worth native Kirk Franklin’s group God’s Property. Since then, he’s worked with everyone from Snoop Dogg to Quincy Jones. Then there’s his longtime collaboration with rapper Kendrick Lamar, a creative partnership that has produced some of the most vital music of the twenty-first century. It takes only a few minutes of talking to him to know that he does not hold most mainstream artists working today in high regard, does not hold most music released today in high regard. So why did he agree to work with Leon Bridges?

“By the time I’ve come into the studio to make a song with you, I’ve already evaluated you with my spirituality and my God.” Does that mean he prayed before deciding to work with Leon? Yes. What was the prayer? Martin wanted to ensure that Leon was the real deal. Specifically, he implored, “God, make sure this nigga ain’t on no f— shit. Amen.”

Martin studied Leon’s entire song catalog and started to sense what the Gold-Diggers sessions would later confirm: “He’s one of those guys that are helping shape the landscape. These are records that you’re going to be able to go back to twenty, thirty years from now. People are so concerned with Billboard. Everybody posts their Billboards, and everybody posts their streaming numbers, but I love that Leon doesn’t care. He cares how many hearts and souls he can assist.”

There was one thing Martin didn’t love at first: going to Gold-Diggers. I ask him when he knew the sessions were going to be something real, and he explodes. “I knew it better be something real, ’cause ain’t no parking at Gold-Diggers!”

Gold-Diggers bills itself as “a bar, boutique hotel, and recording studios all within a single campus.” Think Electric Lady meets a less obnoxious Soho House. The producer Ricky Reed had noticed during the recording of Good Thing that Leon seemed a bit subdued during the day. Turns out that was mostly fatigue from partying the night before. Reed suspected that work-Leon and party-Leon were very different beings. So, his question going into album three was Who’s Leon after dark? “I was trying to get a more direct channel to the man’s soul,” Reed explains.

Reed felt Gold-Diggers was the perfect location for nighttime Leon to thrive. “The whole concept was How do we bring the party to the studio? ”

Martin, though, was skeptical when he first arrived. “I’m painting the picture, so you know the truth. Ain’t no parking. It’s in East Hollywood, you know what I’m saying? The parking structure is, like, two blocks away, in a shady lot with no lock. A shady l-o-t with no l-o-c-k, no lock. Okay? This was the first time I went there. And I’m like, Man, what Ricky got me coming to? So, I get out the car. I walk over to Gold-Diggers. It’s a club, it’s a nightclub. It’s an abandoned night—” Martin sounds truly exasperated. “I’m walking in like, What is this? It’s a joke. I go to the door. I know it got real, ’cause they had the big fancy metal doors. You know when motherf—ers got the metal doors, they trying to protect some shit. You know what I’m saying?”

I don’t know what he’s saying, but I love everything he’s saying. I say, “Yeah.” He continues. “I go through the metal door. I walk through the corridor. It’s a little grimy. I’m like, See, this ain’t my spot. I don’t feel champagne-y. It looked like they smoked cheap weed there. Anyway, I walked to the back, and the first thing I saw before I seen anybody was a beautiful API console. A beautiful API console.” I later learn that an API console is a piece of high-end studio equipment used by the likes of Frank Zappa, Marvin Gaye, Herbie Hancock, and Bob Dylan. “When you have an API mixing console in your studio, you are not playing.” Then he saw Reed. “Ricky’s a happy guy.” Martin listened to some of the tracks the team had already been working on. “When Ricky pressed play, man, I heard some of the most sincere, heartfelt ideas I’ve heard in the past couple of years.”

Reed made sure the sessions always started late and that they flowed freely. “Leon would just be on the mic, usually holding an acoustic guitar, more so flicking it like a drum. And he’d just open his mouth and let melodies flow, half thoughts, some words, some nonwords. The best word for what he did, I guess, is channel. That’s when I felt like we were starting to see the core of Leon, Leon’s spirit in the room. That became the root of all the songs.”

Toward the end of my visit to Gold-Diggers, Leon and I went to a control room and played back the album’s eleven tracks. We’d been in the studio for four hours at that point, and Leon was finally comfortable enough to stop pretending he likes sitting down. He bopped around the listening room, then leaned over a table, fingers spread like a kid waiting to grab the cake-mix spoon, as the album played. He’d primed me all day for this moment. “If you pay attention,” he said, “there’s some really tasty shit in there.” He’d also rejected my suggestion that this album is proof of Miles Davis’s line, “It takes you a long time to sound like yourself.” “Coming Home was me,” Leon explained. “Good Thing, that’s me. Gold-Diggers Sound is me. But it’s totally not dictating what the future me is gonna sound like.” Per esempio, his next project is a Nashville country–R&B album. Beyond that, he’s got an idea for a trap collab with an artist such as Atlanta-based producer Metro Boomin, and another idea for a Black western film that he and I have since discussed teaming up on. Till then, let’s stick with “LB3,” Gold-Diggers Sound.

There are a few songs that I think best help us understand the man behind this music. First, there’s “Sweeter,” a song that Leon decided to release ahead of schedule, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder by a Minneapolis cop, Derek Chauvin, in May of last year.

One of the reasons I imagine it must have been painful for Leon to hear the claims that he was whitewashed is that he has spent his life as a Black man in Texas, with Black parents originally from Louisiana. He remembers the 1998 lynching of James Byrd Jr., in the southeast Texas town of Jasper, remembers immediately fearing for his life. “Because living in Crowley, man? Seen it. There were still remnants of that racist energy. I remember moments of, like, I’m walking my white friend home . . . and somebody stopping, asking her, Are you okay? I was like fourteen, fifteen. Then, walking home, heads yelling out N—r, flicking me off.” Adulthood and fame made little difference. “I still fear rolling through my own neighborhood. I’ve had moments where I was riding my little electric bike and the tire went flat. I had to walk a minute from where I was. It was dark. I live here, but I’m like, What’s the possibility of somebody calling [the police]? ”

Then he grabs his guitar and does something I curse myself for not catching on video. He starts strumming a sort of country ballad about an unidentified victim of police brutality. His voice is so sweet, the whole thing is so simple, so chilling, so surprising to hear sung like a Tammy Wynette or Willie Nelson tune. “That’s how ‘Sweeter’ started,” he says as he stops strumming. He wrote an early version of the song in a hotel room, maybe in Virginia, in 2015. It sat on the shelf, like many of his songs—he says he’s written about a hundred since “Conversion”—in part because he has frequent bouts of writer’s block, and in part because he felt that if he released a country ballad about police brutality, the people he wrote the song for wouldn’t listen. So, he left it alone.

Until one night at Gold-Diggers, when Reed started playing a beat and Martin came in with a chord progression that struck him. “At that moment, I remembered that old country song.” He’s standing now, starts strumming that same country ballad, eyes closed:

Mr. White Man with your black steel

Didn’t expect to see the darkness today

As I

Lay on the pavement covered in blood

While the tears

Of my mother

Rain over me

My eyes well up as I look at Leon Bridges and his guitar. He’s cool about it.

“I had been numb, up to that moment,” he says of Floyd’s murder. “My way of not feeling shit is, like, I just turn it off. I don’t like the way I feel when I totally dwell on it.” But then he saw the video of Floyd. “I remember . . . I was in my kitchen . . . just bawling. I was like, damn . . . That’s . . . that’s my brother. That’s my dad. That’s my . . . homie, you know? It just rocked me.”

That brings me to the second song I want to meditate on with you. “Blue Mesas” opens with the kind of slow, consequential strings you might hear at the end of a war movie. The strings go still, and a man faintly counts—two, three—as the band picks up the beat and melody, and Leon starts to sing, achingly, about his loneliness, a “hurting in my soul.”

Turns out there’s been a mighty cost to Leon’s journey from Rosa’s to the top of the world. “There’s a solitude that comes with success and notoriety. Initially, when I got in the game, I was swept up, and I didn’t express that to anyone. I just had a really hard time, on a lot of levels, being in the limelight.” I wonder why he didn’t tell anyone. “It’s one of those things that you feel is very minuscule, you know? You wonder how people are going to respond. You think they’ll say, Oh, you got everything—how are you feeling that way? But the wild thing is to have everything but still feel that way.”

There was one other issue that made it painful for him to be in the limelight. For many years, Leon Bridges—who is a genuinely beautiful man and one of the most fashionable singers on the planet—hated the way he looked. “I have a very distinct kind of appearance, and I just felt very fearful of how other people viewed me. I didn’t like my nose, you know what I’m saying? Like, I hated it.” I ask if he ever considered a nose job. “I did. I did. I was like, Man, I can’t deal with this. Like, I don’t like the way I look. And I’m doing all these videos. I was at one point scared to even get the opportunity, if I ever had it, to sing at the Grammys, you know? And I internalized all that pain.”

The first sign of trouble came not long after the release of Coming Home, at a fancy club in Paris. Leon was set to perform, but before he went onstage, he had a breakdown. He pulled it together enough to play, but then, a few years later, another breakdown, this time with friends.

“We were just out, like, doing our thing. We had this after-hours hang at this hotel that we kick it at. It came out of nowhere . . . I just started bawling.” He felt trapped. “At that point I was like, Man, I kind of don’t want this, you know? I kind of want to go back to Todd, go back to washing dishes. And I’m dealing with this feeling that I’m not handsome enough to be here, I’m not a good enough songwriter. Just feeling like I didn’t deserve to be in the position that was handed to me.”

When Leon first shared these struggles with me, I decided I wouldn’t tell you about them. But the more he and I talked, over two days in Los Angeles, a long day in Fort Worth, and via a few texts since then, the more I realized I was more afraid than Leon. “I think that we, as men, should just be more transparent,” he told me at one point. He could have drowned his troubles in drugs or booze. He could have stepped away from life altogether. I mean no disrespect when I say he could have gone down the path of Michael Jackson, become a slightly or radically different Leon Bridges. He could have kept internalizing his pain and played tough and strong and silent. But he didn’t. He sat with his best friends, and he cried.

I ask him how dark things got. “I’ve contemplated just, like, not being here anymore, you know? But I never got to the point of acting on it. It’s such a wild thing that something, I guess, so minuscule as not being in love with a part of my body, or my face, or whatever . . . is the thing that causes depression, and that sparks suicidal thoughts. Because, like, I can’t even walk away from it. I can’t just say, Oh, yeah, like, I’m chill, and I’m not gonna be, you know, this guy anymore. It’s like, I’m locked in. You can’t really step away from who I am now.”

A prime example: Leon took me to his father’s home, on the south side of Fort Worth. He spent weekends and summers in this house after his parents separated, when he was seven. In the hallway there’s a photograph of fourteen-year-old Todd; he’s wearing an oversize white T-shirt, holding his baby sister’s hand on Venice Beach as they wet their feet in the Pacific Ocean. That same sister, who’s now in her early twenties, is in the living room when we arrive. She hands Leon a cordless phone. It’s Uncle Bill, one of Leon’s oldest surviving family members and his father’s hero. I hear Uncle Bill softly repeat, “Whenever you have time, come see me. Whenever you have time . . .”

Another sister appears. Toooodddd, she whimpers. She grips him as if she’ll never see him again. Over the next half hour she updates him on her life, including her first experience of ghosting. Leon seems unsure what to say, so just says, Hmm . . . ghosted . . . wild . . . Never ghosted, never been ghosted. He’s not bragging, I don’t sense; he just wants this conversation to end, especially since there’s a photographer capturing the whole thing. His sister shoots back, “Well, you’re famous, so you don’t count. You’re never gonna count, ever.”

Born Again

One Sunday morning just outside Hollywood, Leon and I sat across from each other in an uncomfortable wooden booth at a “plant-based bistro” whose dim lights seemed designed to hide the sad food we ordered. He’d had a late night, and I kept asking pretty dumb questions, so we sat in silence for a good while, picking over our meals, which was fine with me. I had a trump card. Eventually I opened my laptop and played a video that he couldn’t believe I knew about, a video I must tell you about before we’re done.

Way back before he was Leon Bridges, before he wrote songs or played guitar, before his Ford Fusion, before he quit Tarrant County College, Todd Bridges was a member of the Velocity Dance Company of Fort Worth, under the direction of Gypsy Ingram. “He was this tall, shy, quiet kid that stood in the back of the room and did not look me in my face,” Ingram recalled.

Todd had enrolled at TCC following his older brother, who encouraged him to hang with a crew of his own friends, especially “Nemo” Calvin and the Busby brothers, Kenny and Sean. Nemo, Kenny, and Sean hosted jam sessions in TCC music rooms that would go for hours, freestyle singing about everything from heartbreak to Kool-Aid. They started inviting Todd, then convinced him to join Ingram’s company, where he initially felt inadequate, feared he’d never be able to dance like them. (It’s Sean who scolds, “Be reserved, yeah, but that shy shit is disrespectful.”)

One day, after a tough rehearsal, Ingram sat Todd down. “I asked him to come sit with me in the lobby. I said, ‘Look, here’s what I need you to realize. Todd is the only person in the world that can do what Todd does. That’s the young man that I need.’ ” Something seemed to change after that. “Once he allowed himself to know that I was okay with him just being who he was, it was like a switch had flipped.” He worked harder than ever, learned ballet, jazz, modern, African. He became a leader, especially after Nemo and Kenny moved on to professional dance careers. Then, after three years in the company, he got his first solo. Ingram explains the gravity of that: “Getting a solo meant that you had arrived. It meant that I completely and totally saw not just the technical dancer but the artist. You were ready.”

Todd wasn’t so sure. So he and Ingram added a piece of choreography to his performance that featured five background dancers. Nearly two minutes into his five-minute routine, the other dancers spread out in a line facing the audience. Todd bounds from far back on the stage, pirouettes past the others, his long body stretched high in the air. As soon as he lands, he starts to stagger. The background dancers turn away from the audience, turn their backs to Todd, who stagger-dances as if he’s about to collapse. Just before he does, the dancers spin around, encircle him, catch him. They lift his limp body into the air, higher than he was when he pirouetted on his own. In the video I show Leon, the crowd goes nuts. Todd comes back to life. “That lift happened because I needed him to know that he was supported, that he was not out there by himself,” Ingram explained.

It’s the same thing Leon’s friends want him to know when they hear “Blue Mesas.” “Every time I play it for my homies,” Leon tells me, “they’re like, ‘Man, we got you!’ ”

It’s hard to know that when you’re always on the road. So, while there is no silver lining to the coronavirus, it also must be said that this awful plague most likely saved Leon’s life. He got to go home.

When everything shut down, Leon went back to Fort Worth, but Gold-Diggers Sound wasn’t yet complete—he still needed to make one more song. Reed started sending him beats to write to, a sort of Marco Polo remote jam session. One morning Reed issued a challenge: write something by tomorrow. “Bro, I was depressed,” Leon remembers. He woke the next morning with nothing to show. Suddenly, still in bed, the words came to him. “I was like, Spinning ’round, spinning ’round, feeling numb . . .”He rushed to GarageBand. Or, he pulled up GarageBand in a cool, calm manner, as is the Leon way. He recorded his vocals, sent them to Reed. “Born Again,” the last song Leon wrote for his third album, the first song he wrote after finally going home, became the opener for Gold-Diggers Sound.

Feeling born again

Feeling joy again

When all else fails, your love will last forever

Your love will last foreverrr

He wants people to interpret the idea in their own way. “I mean born again not necessarily in the traditional spiritual sense but just feeling like my prayers were answered, of finally having time to slow down.” He rented a house on Lummi Island, near Seattle; stayed there for a week, alone. “It was almost just a childlike wonder, just taking in the beauty, like, Damn, that grass looks nice.” Aside from that far-off retreat, he stayed mostly in Fort Worth, where he often did much of nothing, besides watching his favorite childhood cartoons. “Nostalgia is the antidote,” he tells me. He got closer to a girl he was seeing at the time. That’s not the love he’s referring to in the song, though. “It’s about the everlasting love of God, you know what I’m saying? Then my mother. Then my friends.” Friends like Brandon Marcel, a singer Leon met at one of those Fort Worth open mics back when. “I’m very grateful for him to be there,” Leon says of Marcel, who is now his roommate and part of his touring band. “Because if he wasn’t, I’d be f—ed.”

These are the people I want to meet.

I drove to Fort Worth in early May to spend a long Sunday with Leon and crew. What struck me most about his house, which he bought a few years back, is that you approach the neighborhood, called Monticello, via a redbrick road. Not quite cobblestone, but close enough to signal old-ish money. Josh Block says everyone was proud to see how reasonable Leon’s home was. “I’ve always been, you know, essentially a minimalist,” Leon explains. “Even when I had a little bit of success, I was still rolling around in my freakin’ 2012 Ford Fusion.”

To be fair, you don’t have to be flashy when, hanging on the wall right inside your front door, there’s a photograph of you at the White House, bowing to Barack and Michelle Obama as they grin at you as if you’re their son. In a case on the opposite wall sits Leon’s Grammy. As soon I enter the kitchen, I see his first art purchase, a Gordon Parks photo. Leon takes me around, past the RIAA plaques for Coming Home. “ ‘River’ just went platinum,” he says, in the same tone you might announce the mail has arrived. Above his couch hangs a large painting by a local artist, Jay Wilkinson, which Leon special-ordered. “My pantheon of guys that I look up to,” he says of the image. They’re all hanging out together: Willie Nelson, Ginuwine, Townes Van Zandt, Miguel, Van Morrison, Bob Wills, Guitar Slim, Dr. John, Bobby Womack in an astronaut suit, Leon’s friend Jake Paleschic, Sam Cooke, Bob Dylan, Allen Toussaint, Lee Dorsey, and Frank Ocean. Oh, and Hank Hill, from King of the Hill. “Hank is that quintessential Texan, you know?” Leon explains. “And one of my favorite cartoons.” As we’re walking back to the kitchen, he adds, “He actually plays guitar as well.”

We sit at Leon’s kitchen island as his friends gather. Marcel’s already there, as is Dion, the one who wants me to believe that young Todd didn’t talk. Nemo, Kenny, and Sean roll in after a while. (The Busby brothers enter wearing tricked-out denim jackets, no shirts underneath.) Next comes Abraham Alexander, who connected with Leon by chance when he showed up one day at Shipping & Receiving to meet a friend. He saw someone pushing an amp inside the building, followed them to figure out what was happening, then ran into Austin Jenkins and Josh Block. “If you can hum, come,” Alexander remembers them telling him. The next day he met Leon, and the two have been friends ever since.

Each friend—each brother—tells his story of meeting Leon (or “L,” as many call him), of watching his music evolve, of their own frustrations with the charges that he was whitewashed. “A lotta people don’t know,” Marcel says as we discuss “Sweeter,” “the hood f— with L.” He sees the “Sweeter” video as a prime example of that. Directed by Fort Worth–based Rambo Elliott, it was shot on the same Southside Fort Worth street Leon grew up on and features Leon’s friends, as well as a few of the local gang members—from rival factions, no less—that Leon’s father mentored long ago. “No actors. Nothing fake,” Marcel says. “He wasn’t pressing or paying nobody to do nothing. People showed up out of love and respect.”

I ask folks if they knew how holy Todd was back then. “Hell, yeah!” Sean cries. Nemo, the oldest, adds, “He was endowed with his faith.”

“And then y’all turned him out?” I ask. Sean points at Leon and cries, “Naw, he turned hisself out!” The room becomes a big guffaw.

Leon’s had enough. “Let’s do some shots, man.” He plants a Bluetooth speaker on the kitchen island, starts blasting music. I move over to a slightly quiet corner with Nemo and Sean. Kenny joins after a while, then Marcel. We talk about Fort Worth and the Houston Rodeo and their own dreams. At some point I mention Leon’s struggles with his insecurities. I want to know, from the people who know him best, how Leon overcame those struggles, or at least endured them without self-destructing, because things could have gone way left.

There’s a long silence.

Kenny speaks up first. He speaks for a long time, is listened to by the others. He says that the group has always had a standard that they hold one another to. “His style, his music, where he comes from, everything: it’s been hammered in him to not change it. That’s always been the type of people that we are.”

Marcel has been there for Leon’s darkest moments. “I just reminded him of who he truly is. Reminded him of his value. We know his magic, we know his power, we know who he truly is as a human being. I know it may sound corny, but God created you that way. And you have the opportunity to make your flaw beautiful, so that the next person, the next generation, can look at you and say, ‘I look up to you.’ Because you didn’t change yourself. And something that I’m struggling with, you took and made it beautiful, or you took it and you faced the struggle despite it.’ ”

Marcel always stresses to Leon that he doesn’t have to make some dent in the universe, or ever write another song. “Go do all the other shit, but I’m a rock. And I’mma be there for you ten years from now, when maybe this ain’t all here. That don’t matter to me. It doesn’t matter to nobody that’s around him. It’s about you being healthy, about self-love, not depending on people’s applause to be happy.”

Earlier that day, as Leon drove me to Rosa’s Café, I asked him where he was on that journey. “I’m way closer to more self-love and acceptance of who I am,” he said with no shame or hesitation. “I can look in the mirror and be totally fine.” I asked what helped him get there. “It has happened probably within the past year, really . . . being home, being away from it all. I’ll see where I’m at when I’m back in it.”

By the time you read this, Leon Bridges will be back in it. Should he happen to read this himself, I want to leave him with a dose of nostalgia, a sequence I hope to still remember when I’m dead.

At one point during my sidebar with Nemo, Sean, Kenny, and Marcel, Leon walks over and picks up a nearby amp, moves it to the kitchen. He’s switched outfits from earlier, when he had on loose blue jeans, a brown-and-tan windowpane flannel shirt, and dark-brown vintage Gucci loafers. Now he wears slim cream trousers, a cream knit top, and a different pair of vintage Gucci loafers, also cream. (Gucci should name Leon as an ambassador.) When I met him in Los Angeles, his hair was in bantu knots. Now it’s braided, under a velvet “Woodhaven Fort Worth” fitted cap. His friends had promised me this moment would come. It’s time for a jam session.

Leon sits on the amp, and everybody stands or sits around him. He sings as he plays, some real songs and some freestyles, just like the old days at TCC. Kenny freestyles a verse, and then Sean, and later Marcel, who performs an original song as Abraham Alexander plays guitar, and the crew goes wild. This continues for over half an hour, ending with an R&B group singalong, led by Leon on the guitar. The song ends, and I guess Leon is done with the guitar and the harmonies and the crooning. He goes to his phone. From the Bluetooth speaker comes the up-tempo hip-hop beat “Club Rock (Everybody Rockin’),” by Yung Nation, a Dallas group that also happens to be in Leon’s painting. All of a sudden, the kitchen becomes a club. Everybody pushes the counter stools back, grinning as they toss the first few lines back and forth. The bass drops. “Get the club rockin’! Everybody rockin’!”

And, well, everybody starts to rock it, one by one. It’s not a dance-off, exactly, but nobody’s about to lose whatever there is to lose. Leon stands against the wall near his refrigerator, drinking flavored water (or White Claw?), hyping this one and that one up, lifting those eyebrows, grinning, Aye! It’s almost as if he’s at somebody else’s house.

Then, his drink goes on the island . . . he jigs into the crowd, he dips, his friends circle around, press close, ecstatic. He turns toward the front door, which is already open. He’s crouched like the hood version of a Russian squat dancer. Aye! . . . Aye! The crouching mass lurches forward, past the Gordon Parks print in the kitchen (“Stand out stand out go / Body rock the flo’ ”) through the hallway, past Leon’s Grammy in the living room, past the photo of Leon and Barack and Michelle at the White House, out the damn front door—I still can’t fully believe it—across the porch, down the walkway, off the curb, into the street.

Each one takes a solo now: Nemo rocks it, Sean rocks it. Abraham retrieves a suede cowboy jacket from his car, uses it as a James Brown cape as he rocks it, passes it to Kenny while Kenny rocks it. As if they’ve done this a million times, they move in formation, two lines of four, dropped low, huddled together, swagging three steps to the left, three to the right—Aye!—breathless with laughter, breathless because this has gone on for a long time and it’s still not done. They’re up again, another round of solos, they know the song is ending soon. Then—then—Leon, all of a sudden, launches away from the group. Everyone stops and watches: his friends from the middle of the street, me from the curb, his neighbors from their windows, as Leon pirouettes—Aye! . . . Aye! . . . Aye!—a tall cream blur spinning solitary down the middle of a quiet street in one of the nicest neighborhoods in Fort Worth, Texas. You really should have been there.

I watch Leon Bridges stumble back to his friends from down the road, stumbling drunk with laughter, and I think back to a dinner we shared in Los Angeles.

Dusk had settled over the courtyard restaurant. We were one margarita and some lamb ribs in when I asked, “What do you think six-year-old Todd, singing ‘Hakuna Matata’ in his room, would say to you now?”

Leon looked down at his plate, or down in his memory at that little boy. “Hmm.” He rested his hands on either side of the table. “Six-year-old me. Wow. Man. What would he say?” His brows lifted, that sly smile flashed in the dark. “Probably I love what you’ve done with the place.”

This article originally appeared in the August 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Texas Son.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Music

- Fort Worth