Academic historians weren’t much impressed with T. R. Fehrenbach’s Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans when it appeared in 1968. One reviewer criticized Fehrenbach’s decision (in his own words) to eschew “irritating footnotes” that would interrupt the book’s narrative flow. Another

scholar dismissed the author—who, after graduating from Princeton and serving in the Korean War, had worked in the insurance business in San Antonio—as a “dilettante” and offered a withering assessment, saying, “All in all, this book is a failure.”

Lay readers, however, returned a very different verdict, embracing Lone Star to such an extent that it may be the most widely read history of the state. A decade ago, a journalist in the New York Times noted its canonical status, placing it in the company of John Graves’s Goodbye to a River and Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove.

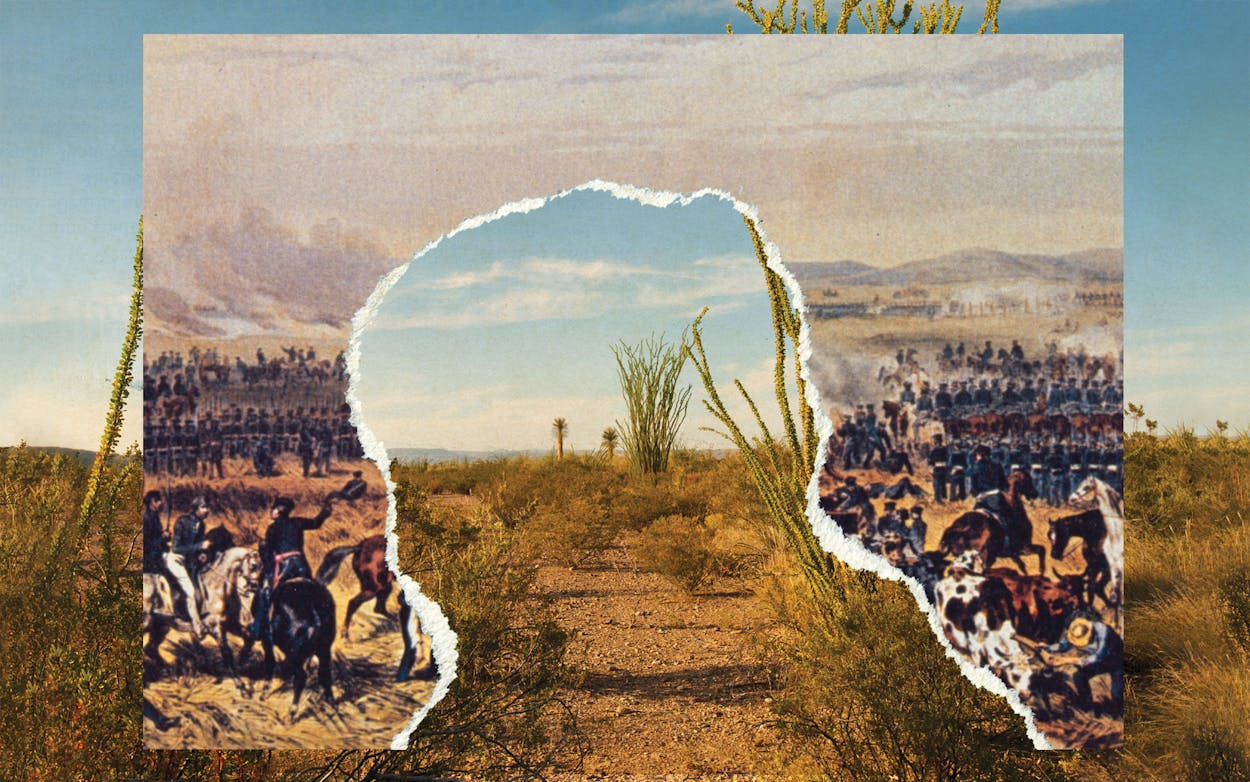

Although Fehrenbach insisted that Lone Star “was not written to destroy myths but so far as possible to cut through them to the reality underneath,” the book established a creation story all its own, rooted in the idea of “blood and soil” (the title of an entire section of the book as well as a chapter within it), a slogan popularized in Nazi Germany to explain the relationship between race and nation. According to Fehrenbach, the brutal contest among different racial and ethnic groups for control of Texas was more violent and protracted than anywhere else in what became the United States, cultivating among its white victors the “sense of being a chosen people,” which imbued them, in their minds, with “immediate moral superiority, in action, over their enemies.” This perspective may explain Fehrenbach’s intense focus on the crucible of the nineteenth century—the twentieth century is confined to around 10 percent of the latest edition’s 725 pages—as well as the book’s enduring appeal, given his crowd-pleasing attention to heroic episodes in Anglo-Texan history, from the Texas Revolution to the rise of the cattle kingdom.

Even those readers not enamored with Lone Star’s Texceptionalism might grudgingly acknowledge its merits. For one thing, Fehrenbach strives consistently to situate events occurring in Texas within the wider sweep of U.S. history. He takes into account, for instance, the European imperial rivalry in North America and the bitter divide over slavery that culminated in what he refers to—using the term popular among Confederates and their sympathizers—as “the War Between the States.”

For another, he often writes beautifully, especially about the natural world: “Over the whole land the sun burned, not the distant friendly orb that filtered light through European forests, but a violent, brassy engine that browned the earth and made the hillsides shimmer with heat.” Such vivid prose is typical of his oeuvre, which included eighteen nonfiction books as well as hundreds of columns published in the San Antonio Express-News over nearly three decades, the last of which appeared just months before his death in 2013 at the age of 88. (He also wrote a handful of pieces for this magazine.)

But to encounter Lone Star today feels like stumbling—and then lingering—on an explicit website, considering the almost pornographic nature of its racism. “Amerinds,” as Fehrenbach calls the Indigenous peoples of Texas, are described as “barbarians,” “red vermin,” and an epithet unprintable here, a formidable obstacle swept aside by an onrushing tide of white settlement. In the long battle for dominance in South Texas, Fehrenbach explains, “the Mexican, to keep the records straight, slipped from deviousness to outright treachery,” citing the dubious statistic that “Mexicans killed more Texans by the result of parleys than on all the battlefields.”

In the author’s hands, African Americans have no agency whatsoever. For instance, in describing the turmoil following the Civil War, he writes, “The situations that became utterly intolerable to whites—the Negro police, the Negro senators, the Negro society quartered on their towns—were all brought about not by Negroes but by Southern Scalawags and Northern Caucasians.” Little wonder that he considered this era “the most disastrous period in Texas history.”

Fehrenbach, who served as head of the Texas Historical Commission from 1987 to 1991, surely heard complaints about the unvarnished white supremacy that suffuses Lone Star, which sheds light on the defiant tone he struck in a foreword he prepared for an edition of the book published in 2000. “As a construct,” he wrote then, “history is too often revised to match contemporary views. It has been said that each generation must rewrite history in order to understand it. The opposite is true. Moderns revise history to make it palatable, not to understand it. Those who edit ‘history’ to popular taste each decade will never understand the past . . . and for that reason, they will fail to understand themselves.”

This, of course, is nonsense, a view held by few professional historians. Anyone worthy of that title revises narratives about the past as new sources of information and new methodologies become available. Alas, echoes of Fehrenbach’s inflammatory defense of Anglo-Texan triumphalism can be heard, loudly, in the hysteria that has recently convulsed public schools over so-called critical race theory—a method for examining systemic racial discrimination that has been grossly mischaracterized by those who prefer that schoolchildren be taught little or nothing about the state’s long struggle with racial issues. In that way, Lone Star, lamentably, is very much a book for our times.

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Goodbye to a Mythos.” Subscribe today.

Image credits: Landscape: Education Images/Universal Images Group/Getty; Battle: MPI/Getty