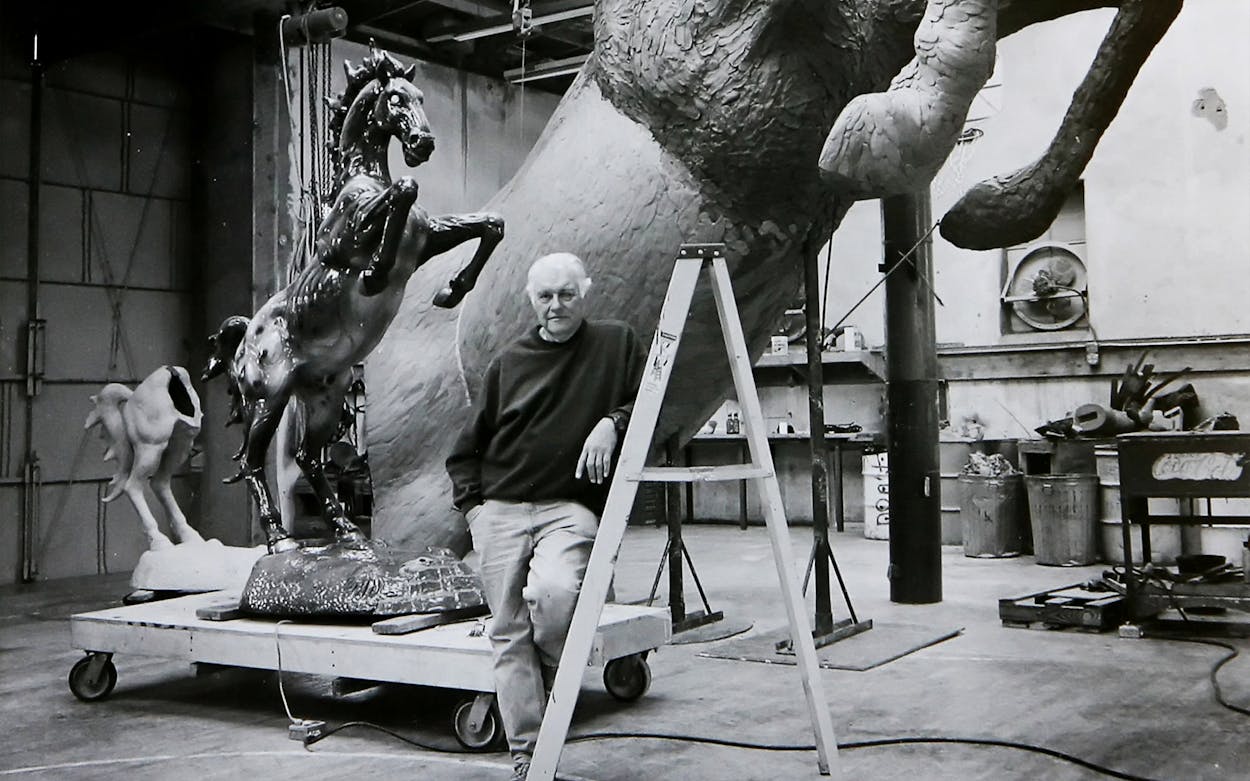

There’s a good chance you’ve come across a sculpture by El Paso–born Luis Jiménez at some point, whether you’ve known it or not. Perhaps it was Vaquero, the pistol-waving Mexican American cowboy on a bucking bronco that has stood in front of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., for decades. Or maybe it was Blue Mustang, the massive, demonic-seeming horse that greets arrivals to Denver International Airport, and which tragically killed Jiménez when a piece of it fell on him in his New Mexico studio in 2006. Jiménez’s monumental fiberglass sculptures are all over the U.S., often made to order on local themes (a steelworker in Pittsburgh, alligators in the main plaza of El Paso), to the point that Jiménez can be considered one of the quintessential—and unavoidable—public artists of his era.

Jiménez was much more than just a show pony for garish public sculptures, however. Such is the argument of the new exhibit “Border Vision: Luis Jiménez’s Southwest,” at Austin’s Blanton Museum through January 16. Blanton curator Florencia Bazzano would have us know that Jiménez was also a thoughtful craftsman at the intersection of Pop Art and rasquachismo (a streetwise, make-do Chicano art style), a student of both nature and classic cars, and a pioneering believer that the Hispanic immigrant experience and colorful barrio aesthetics deserve a place in high art.

“Border Vision” is a two-room exhibition built mostly out of works from the Blanton’s permanent collection. It presents a purposefully narrowed, border-centric view of Jiménez’s life and career. We learn about Jiménez’s childhood as the son of a neon-sign shop owner in El Paso, his excursions into the nearby mountains as a boy to explore and to observe wildlife, his teenage fascination with restoring classic fiberglass-exterior cars, his side job when he was living in New York as a social worker organizing dances for Hispanic youth, and his return to the Southwest and New Mexico in the seventies. We are reminded that he is a distinguished alumnus of the University of Texas at Austin, the parent institution of the Blanton. The show skips over Jiménez’s New York–era Pop Art and more far-flung commissions, bringing him closer to a Texas audience and streamlining his persona for a present era when artists are, more than ever, expected to speak to and for their communities of origin.

The Blanton show is built around two big, classic Jiménez fiberglass sculptures—Progress II, which depicts a vaquero roping a longhorn, and Border Crossing (Cruzando el Rio Bravo), another of Jiménez’s most iconic works, which catches a migrant family in the moment of crossing the Rio Grande. Progress II is mythic and extremely kinetic, featuring frightening, neon equine eyes like in Blue Mustang, plus several details that nod to Southwestern history and nature, including a broken barbed-wire fence, an indigenous warrior’s skull and spear tip, and various native plants and animals.

For many Texas-based visitors to the Blanton, Border Crossing may be a familiar sight, but it is still probably the most important work in the show and the one that is most likely to stand the test of time and be looked at by future generations as an emblem of our era. Its vertical, totemic composition—a woman, eyes ahead, clutching a baby in her shawl, sitting on the shoulders of a man who, eyes downcast, steps through the swirling waters of the Rio Grande—is simple and perfect. It captures a timeless vision of a family’s sacrifices and forward-looking hopes. The work would be powerful enough on that level alone, without the added present-day political resonances around ever-larger migrant flows and ever-greater mortality risks faced by families who pursue a better life in the U.S.

Border Crossing was conceived in part as a tribute to Jiménez’s father and grandparents, who came to the U.S. from Mexico without documents. It works on me in much the same way as a Renaissance pietà or church sculpture of the Holy Family. It feels infused not only with the mythic story of the figures depicted, but also with the specific personal experiences of everyone who has laid eyes on the work over the years and felt their own family history, grievances, and hopes reflected in it. Jiménez made several copies of the sculpture, which can also be viewed at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and the University of Texas–San Antonio.

The Blanton is careful to offset Border Crossing’s seriousness with more festive, celebratory visions of Mexican and Chicano life. For instance, Fiesta Dancers (Jarabe), Working Drawing No. 2, the largest wall hanging in the exhibition, shows a courtship dance well-known on both sides of the border, with the man in chaps and the woman in a Mexican flag–themed dress. Their faces speak to lives of hardship, while their bodies are sensual. This is another classic Jiménez image, which he has reproduced in sculpture elsewhere.

Perhaps the most interesting juxtaposition of the Blanton exhibition is a pair of lithographs—Air, Earth, Fire, and Water and Cholo and Van with Popo and Ixta. Both works depict the Aztec-era myth of Popocatépetl (El Popo) and Iztaccíhuatl (Ixta), deities who share the names of the two large volcanoes to the southwest of what is now Mexico City. In this Romeo and Juliet–like tale, Ixta, a beautiful princess, is misled into believing that her beloved Popo, a valiant warrior, has fallen in battle. She lies down and dies of a broken heart. Upon her burial, Popo lays down his smoking torch and dies as well.

Jiménez depicts this myth first straightforwardly, in Air, Earth, Fire, and Water, in which we see the four elements come together in the moment of Popo’s grief. Then he repeats it, in transgressive celebration of lowbrow Chicano culture, as a mural painted on the side of a panel van in Cholo and Van with Popo and Ixta. It’s tempting to read the latter work as Jiménez’s justification for his use of bright and pastel colors, comic-book pictorial styles (including bulging muscles and swelling bosoms), and muscle-car fiberglass as a go-to sculptural material. He is proudly placing himself in the same artistic lineage as the “cholo” van driver, daring the institutional art world to call him low-class or illegitimate.

Last but not least, “Border Vision” offers a few valuable glimpses of how Jiménez drew himself in the context of heritage and culture. The exhibition includes two self-portraits, one in which the artist dances with a seductive calaca, or skeleton, and one in which the artist’s own skull is made visible through his skin. Both make clear reference to traditional Day of the Dead celebrations in Mexican and Mexican American culture.

These gloomy but charismatic prints are another hint that, beyond the horses and cowboys and gaudy public art, there’s a more personal, magnetic Jiménez waiting to be discovered by a new generation of artists for whom he will feel like an ancestor spirit. “Border Visions” is not quite big and well resourced enough to fully unpack that discovery, but we can hope that a major Jiménez retrospective will happen in the coming years—according to Bazzano, the last one was in the mid-nineties. The outlines of what we’d find in such a retrospective are visible here, in a mid-century barrio kid made good in the art world, who was proud of his Chicano roots and in constant, fruitful search of iconic ways of paying tribute to them.