Mack McCormick loves to tell the story of Joe Patterson and the quills. Patterson was a musician from Alabama, who had performed at the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island in 1964. He played the quills, or panpipes, like the ones the dancing goat-god Pan is always pictured waving. But Patterson, a childlike man who sometimes threw violent tantrums, wound up in an Alabama asylum, where McCormick went to visit him in 1968. He had no quills to play, so McCormick paid two guards to go down to a nearby river and cut some reeds. As rural musicians have done for ages, Patterson trimmed and hollowed the reeds, holding them together with white hospital tape instead of the bright rag strips he once favored. Then he played his quills as he did growing up, just as people had played them for generations. To McCormick, listening to Patterson’s “lovely jumble of sound”—he also whooped and banged a tambourine—was like hearing the first music ever played. “People had to invent music to suit themselves and their community,” McCormick says. “It’s the purest kind of tradition.”

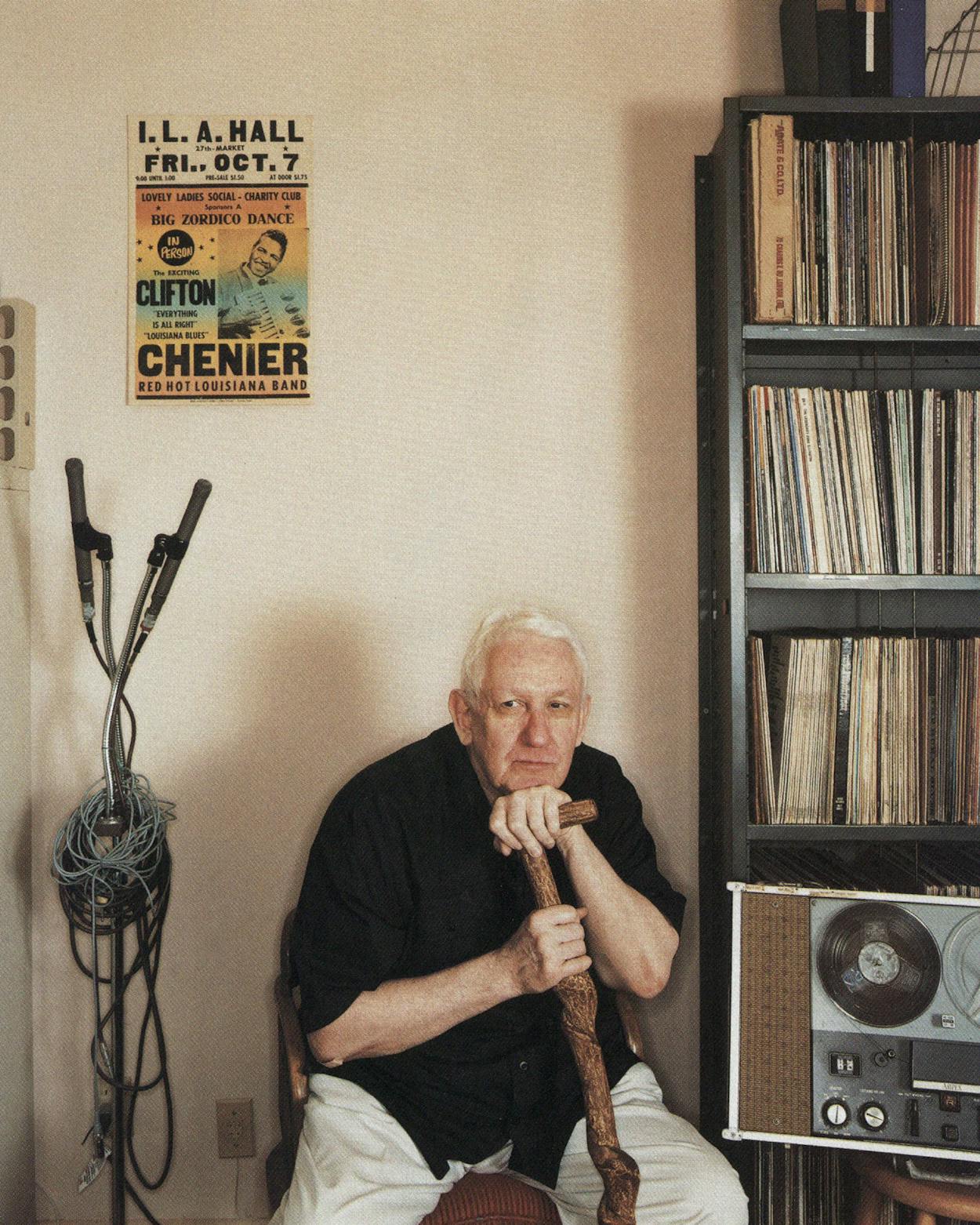

Sitting in his northwest Houston home last September, McCormick pulled out ten reeds held together by faded brown tape. They were Patterson’s, and McCormick handed them to me. Instinctively I held them to my lips and blew a disastrous tune. McCormick didn’t mind; actually, he seemed pleased. For a few seconds I was directly linked to Patterson as well as to Texas quills player Henry Thomas and thousands of unknown pipers. For McCormick, who has spent the better part of his 71 years chasing down singers, songs, stories, games, recipes, and other folklore, it’s all about connections—between citizens, between artists, between ideas, and between the stories that bubble in his brain after a lifetime of collecting: how he wrote songs with Lightnin’ Hopkins, how he unplugged Bob Dylan, how Mance Lipscomb made him weep. One story inevitably segues to another, often in unpredictable ways. At one point McCormick told me about a version of the croquetlike game roque that was played in oil fields with a ball and giant mallets, and before long he was talking about Lipscomb, who had lived in Navasota. Then he paused, as if looking for something in a pocket in his brain, and said, “Oh, I know, this is the connection,” and he was off again.

“Mack is one of the most important Texas vernacular-music historians,” says Arhoolie Records president Chris Strachwitz, himself a collector for forty years. McCormick “discovered” and recorded living musicians, like Lipscomb and Hopkins, and reimagined the lives of dead ones, like Robert Johnson. He’s written dozens of magazine articles and album liner notes. He’s worked for the Smithsonian Institution. He’s knocked on more doors than a traveling salesman, seeking . . . connections. “Mack set out to live his life on his own terms with all the passion of someone who has made a vocation of his avocation,” says Peter Guralnick, the author of many acclaimed music books, including two about Elvis Presley and several about the blues. “He pursued it in territories where there were no maps and no rules.”

After McCormick’s decades in the field, he has amassed one of the most extensive private archives of Texas musical history in existence. He has hours of unreleased tapes, perhaps twenty albums’ worth of field and studio recordings by Hopkins, piano players Robert Shaw and Grey Ghost, Lipscomb, zydeco bands, and the polka-playing Baca Band. He took pictures everywhere he went and owns some 10,000 negatives, many of famous artists and many more of the army of unknowns he rescued from oblivion. Then there are his notebooks, which are like the Dead Sea Scrolls, holding thousands of pages of field notes and interviews testifying to the amazing diversity of Texas music, not just blues. Maybe the most important thing McCormick did was to document the lives and music of a broad group of some of the American century’s most-influential musicians, people like Lipscomb, Thomas, Hopkins, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Leadbelly, and Blind Willie Johnson. Much of the archive sits in storage in Houston, much more at a place McCormick owns in the mountains of Mexico. And it’s in danger. The pages are fading, the tapes need restoring, and McCormick is sufficiently hoary to worry about dying suddenly with no home for it all. As Strachwitz says, “It would be a horrible tragedy if all his stuff disappeared.”

McCormick calls his archive the Monster, a term of both affection and fear. Inside the Monster are secrets—on the origin of the blues, on the story of Texas music, and on the lives of some of the greatest musicians in American history. But the Monster holds secrets about McCormick too, about “some destructive block,” as he puts it, that has kept him from completing the many history books he has begun over the past half-century. “I’m the king of unfinished manuscripts,” he told me with a self-conscious, pained laugh. Maybe it was the agony of writing. Maybe it was the seclusion. Maybe it was just the blues.

McCormick shuffles around the home he’s lived in for thirty years with a cane, favoring a bad left knee. Last fall he suffered an aneurysm in his left leg, and it still hurts. He has snowy white hair and big glasses; he looks a little like crime writer James Ellroy, though without the bulldog ferocity. He has a reputation for being a crusty, reclusive old crank, and he rarely sits for interviews. Indeed, it took several phone calls and a long letter expressing my interest in doing a story on his search for Robert Johnson before I received a reply. No, he was not interested in the story I proposed, but he would cooperate on one that called attention to his collection. He was looking for a benefactor, someone to save it, and he invited me to see it firsthand. I jumped at the chance.

I spent several days with him last fall and winter, and though he can be irascible, he is also sweet and generous to a fault, sharing history, tips on research techniques, and a somewhat holistic wisdom about the world. “All I learned,” he wrote me later, summarizing his life as a folklorist, “was what others found staying home with the neighbors. Each of us are connected by an infinite number of threads.” Though he has spent his life illuminating those threads for everyone else, sometimes he himself has lost sight of them.

“He’s a strange guy,” says Guralnick. “He’s an honorable guy.” Both traits have gotten McCormick in trouble.

Have you ever heard the lyric ‘If you get your business in a fix/You better go see Dr. Dick’?” McCormick asked as we drove down a street near his house. “Well, Dr. Dick was my grandfather.” Richard McCormick was a Waco doctor who ran the city health clinic, where he treated venereal disease. His nickname became well known and eventually found its way into local folklore and song verses sung by Blind Lemon Jefferson, among others.

Dr. Dick’s grandson, Robert Burton McCormick, was born in 1930 in Pittsburgh to Gregg McCormick, a DuPont factory rep who traveled the country showing doctors how to use x-ray machines, and his wife, Effie May, an x-ray technician. They divorced two years later, and their son grew up shuttling between them, living at various times in Texas, Ohio, Alabama, Colorado, and West Virginia. Robert’s father, an informal folklorist, would drive him around Dallas, pointing out history and characters, including street musicians in Deep Ellum. “Everywhere we went, he knew something,” McCormick remembered. His father took him on demonstration trips to West Texas, talking about local lore and music heroes. The shy, bookish boy found adventure in the stories and meaning in their telling.

In high school McCormick was a jazz and swing fan, and in 1946 he got a job at a ballroom in Cedar Point, Ohio, as a gofer for Buddy Rich, Stan Kenton, and other musicians who came through to play a radio show that was broadcast nationally twice a week. Later that year, on a trip to New Orleans, he met Orin Blackstone, who was compiling a four-volume discography called Index to Jazz. Blackstone was so taken with the young jazz buff, who was by then living in Houston with his mother, that he made him the Texas editor for the final two volumes. In 1949, at age nineteen, McCormick became the Texas correspondent for Down Beat magazine, interviewing everyone from Louis Armstrong to Frank Sinatra. “Mack,” as he became known, began promoting big jazz shows, managing and booking bands, and producing recording sessions.

One afternoon in 1949, in downtown Houston near Union Station, McCormick quite literally heard his calling. He wasn’t in the habit of stopping strangers, but something about a tall, old black hobo carrying a banged-up guitar and a busted kazoolike whistle made him curious, so he asked him questions and then asked him to play. The man’s words and music were gibberish, but his vigor was contagious. McCormick didn’t realize it at the time, but he was doing his first field research.

He worked all over—as an electrician on an offshore barge, as a short-order cook, as a carny in Oklahoma, as a taxi driver and an aspiring playwright in Houston. “In each job,” he told me, “I found myself intrigued by the virtually unknown, unexplored body of lore that characterizes a working group”—the limericks, betting games, initiation rites, and especially music. Driving the cab in Houston opened McCormick’s eyes to the diverse sounds of the state: acoustic blues, Czech songs, Texas swing, conjunto. “People thought folk music was over,” he said. “I realized that wasn’t true.” He began recording ballad singers, fiddlers, and bluesmen. He even managed Lightnin’ Hopkins, or tried to. The mercurial bluesman, who had made scattered recordings for a dozen labels in the forties and fifties, had disappeared in the haze of the desultory blues life. McCormick found and recorded him in 1959 for Autobiography in Blues and brought him back, and for the rest of his life, Hopkins was known as a giant of the Texas blues.

In 1960 McCormick brought together and edited nine years of country, folk, blues, and zydeco songs that he and other folklorists had collected. He whittled them down to two albums, A Treasury of Field Recordings, Volumes 1 and 2, and wrote long, detailed notes in booklet form at a time when most albums had cursory back-cover liner notes. The albums were a revelation, showing how musically rich Houston and East Texas were—Saturday Review called the first volume “one of the most exciting and valuable folk music collections in years”—and established McCormick as a leading American folklorist.

The way to do field research,” he told me, “is always from a standpoint of ignorance. Don’t decide beforehand what you want to find—leave your preconceptions out of it. I’ve always found it exhilarating to knock on doors. I’d stop in a town, knock on someone’s door, and say, ‘I’m lost.’ Or people would be playing dominoes and I’d say, ‘Can I watch?’ Get friendly with people. After awhile, ask a bunch of questions at once, get them agitated, sit back, and they start answering them.”

His method involved what he called a grid search: He would take a block of four or eight counties, start in one, head east, return via the next county north, and then crisscross counties in subsequent trips, stopping in every grid on his map. He’d go to the county seat first, find some men talking on the front porch of a store, assume the guise of innocent ignorance, and ask questions. “As soon as enough people tell you about something or someone,” he said, “click, you’ve got it.” Back in the car he’d jot notes and move on. At the motel that night or back at home, he’d type or write up his notes. Later they’d go into one of his many file cabinets.

One name that kept coming up on grid searches in Grimes County was a sharecropper named Mance Lipscomb. With the help of Strachwitz, McCormick found the never-recorded Lipscomb in 1960 at his two-room Navasota home and got him on tape. McCormick talked Strachwitz into making Lipscomb the first release for his new label, Arhoolie, and the debut featured McCormick’s exhaustive liner notes, showing how the artist was a connection to the pre-blues past—a “songster” who had been playing ballads, reels, hymns, dance tunes, and blues for most of his 65 years. McCormick had a real rapport with Lipscomb, and while Lipscomb’s wife, Elnora, kept their grandchildren quiet in the other room, McCormick recorded him in the bedroom, so close their knees were touching. A year later, in a Houston studio, the two recorded again as McCormick’s mother lay dying in a hospital a few blocks away. When Lipscomb sang “Motherless Children,” McCormick began weeping and ruined the take; Lipscomb did the song twice more, though both men had a hard time keeping their composure.

In 1960 McCormick signed on with the U.S. Census Bureau and asked to cover Houston’s Fourth Ward. When his day working for the government ended, he would pound the pavement for another four hours, and soon he had uncovered a fascinating pattern: In one urban neighborhood there were two hundred professional piano players. They played a style of rollicking barrelhouse that, McCormick found, went back to a man named Peg Leg Will, who used to play for people on the porch of an Italian grocery store. Young folks would hear Will play and hop up on the piano, imitating him and eventually coming up with their own neighborhood style, one that was different from the barrelhouse playing in the Fifth Ward, just a few miles away. It was what McCormick later called a “cultural cluster—an outburst in place or time when something previously unknown becomes part of our culture; that point where innovators bring forth a new language, slang, music, religion, game, ritual.” McCormick had something of an epiphany about the distinction between neighborhood and state, how a local style will become a regional characteristic—”The thing,” McCormick wrote me later, “that visitors sense when they say to themselves, ‘This is Texas, this is not Vermont, and it is neither the weather nor the rocks which make it so.'”

Where do things come from and why? Drunk with the music and the stories he was hearing, McCormick began to hatch grand plans: a massive book on the origin of the blues and another on the Texas blues. He had a co-writer on the latter, English blues scholar Paul Oliver, and throughout the sixties the two sent research and chapters across the Atlantic. In his fieldwork McCormick was finding that the trails of many of the dead Texas bluesmen were still warm. For example, he found and interviewed the family of Blind Lemon Jefferson, who had died in 1929. Jefferson’s sister, Carrie, who lived in the tiny north-central town of Wortham, told McCormick that her brother didn’t want people to know he was blind, so he would nonchalantly escort her around Dallas, plucking the guitar he carried as an echo device to guide him. She gave McCormick a real treasure, a photo of her brother that had never been published (only one picture of him has been). In it, Jefferson is leaning against a building, plump and relaxed, his tiny glasses on his face.

McCormick literally picked up Leadbelly’s trail in the little communities at the end of the dead-end roads along the Red River where the folk singer lived as a young man in the early 1900’s. Most Leadbelly scholarship concerns his life as a New York folk hero after he was famously pardoned twice—for murder in 1918 and attempted murder in 1930. McCormick talked to the relatives of two people Leadbelly had killed long before that: “He would go down those roads, get a woman, settle down for awhile, then get into a pattern. Drink, pick a fight, hurt a man. Drink, pick a fight, kill a man. He’d just get into fights all the time.”

When McCormick wasn’t taking notes or working on the book, he was making tapes: prison work songs, bawdy folk songs, truck-driving songs, cowboy songs. He began collecting things other than music, like toasts (the black poetry that would one day become rap), recipes, and oral histories. He took pictures of the work of visionary artists and chronicled local rituals. McCormick would buttonhole anybody who looked promising. At his home office he opened a file and showed me a page of typewritten field notes (“page 2096”) that tells of his stopping in Fayetteville in 1962 and speaking to three musicians in a pickup truck on their way to play a dance. The leader, Lee Wormley, age fifty, “has only been playing a short while; then hired 2 youngsters to make rock and roll; Wormley keeps the kids in line and buys the hit records he wants them to imitate.” Though McCormick didn’t learn much from them (or from a former member of the band, who was “inarticulate, near moronic and almost certainly an inept musician”), the trip allowed him to write about the excellence of most Texas farm-to-market roads and then speculate that this had something to do with the great ease with which rural blacks were moving to cities. Even when he struck out with music, McCormick would score some history.

In 1964 he married a Houston girl, Mary Badeaux. While she worked as an administrator in the microbiology department at the Baylor College of Medicine, he wrote for magazines, newspapers, and educational TV shows in Houston and made a little money from the occasional folklore-society grant or wealthy patron. Throughout the decade, McCormick also booked some of his artists at clubs and helped them make records. He took Mance Lipscomb to play in Corpus Christi and also produced three of his albums for Reprise Records. He co-wrote some songs with Lightnin’ Hopkins—one, called “Happy Blues for John Glenn,” became a minor hit. Working with McCormick, though, wasn’t always smooth. According to Strachwitz, “Mack could be gruff, almost dictatorial. He’d say, ‘That’s not the way it should be.’ When he recorded Mance for Reprise, he made him do ‘Trouble in Mind’ several times. Mance got mad and said, ‘I’ll never sing that goddam song again.’ ”

In 1965 revered folklorist Alan Lomax, aware of McCormick’s work, asked him to bring a Texas prison gang to the Newport Folk Festival to sing work songs. The Texas attorney general wouldn’t permit it, so McCormick found a few ex-cons who wanted to go, including Chopping Charlie Coleman, known throughout the Texas prison system for his strength in the fields with a hoe, and drove them there himself. The singers had never sung together in front of a microphone, much less in front of 20,000 people, and McCormick was anxious to give them a brief onstage run-through. But the previous act wouldn’t get offstage: It was Bob Dylan with his first electric band. In a matter of hours, Dylan would offend the folkies with loud rock and roll and change popular music forever, but McCormick didn’t care about that: “I was trying to tell Dylan, ‘We need the stage!’ He continued to ignore me. So I went over to the junction box and pulled out the cords. Then he listened.”

Later that year McCormick started a label of his own, Almanac Records. His first release was by Robert Shaw, a Fourth Ward piano player who had been playing since the twenties but had never recorded. McCormick again wrote a detailed booklet, connecting Shaw to Peg Leg Will. Nat Hentoff named the album “Best of the Month” in the December 1966 issue of Hi Fi/Stereo Review, noting, “McCormick promises more illumination to come from Almanac on such relatively unexplored themes as The Negro Cowboy; Truck Drivers: Songs, Lore, and Hero Tales; and the Legacy of Blind Lemon Jefferson.” But Almanac never released another album, and those tapes remain in storage.

McCormick’s field research brought him to the attention of the Smithsonian, and he began working there in 1968, when Texas was the featured state in the summer Festival of American Folklife in Washington, D.C. His title was “cultural historian,” and he sought anything and everything of interest: quilts, dolls, recipes, games, handcrafted chairs. McCormick even wrote to Lyndon Johnson and asked if he’d like to do a workshop on telling tall tales. “I knew he liked to do that,” McCormick remembered. The president said no but showed up anyway, and for fifteen minutes told whoppers. (“He went over great with the crowd,” McCormick told me.) Each year the festival featured a different state, and McCormick traveled there to do grid searches beforehand, knocking on doors and looking for people to bring to Washington: a silversmith, a sand-caster, a garlic braider, a cowboy singer, a dulcimer-maker. “It’s healthy to have an idea who lives with us,” McCormick said of his diverse finds. “You get an enhanced sense of who your neighbors are.”

During this time, McCormick was filling file after file with titles like “Bottlenecks and Hang-ups” (about the erroneous idea that Mississippi is the only place where people played bottleneck guitar; they did in Texas too) and “Wild Ox Moan” (about the unicorn legend reappearing as a West Texas myth). But all was not well with one of his biggest projects, The Texas Blues, for which anticipation had been building for more than a decade. By 1971 McCormick and Oliver had 38 chapters done, but their relationship was breaking down. One problem, says McCormick, was they were collaborating long-distance without the benefit of copiers, fax machines, or computers. Oliver says it was also a matter of different working methods. Plus, he says, “Mack could be insistent about saying, ‘You will do such and such by such time.’ I don’t work that way.” Both got so burned out that they stopped working together. They haven’t spoken to each other in thirty years.

McCormick, however, had other things to think about. In 1971 his daughter, Susannah, was born, and he was in the middle of tracking down the most iconic American roots musician of the century, Robert Johnson, a dead bluesman about whom nobody knew much of anything—not even what he had looked like. He was thought to have lived and died in Mississippi, where he was poisoned by a jealous woman or an angry husband, and other folklorists had been on his trail. In 1970, while working for the Smithsonian, McCormick came across a copy of Johnson’s death certificate. He found the names of a couple of witnesses to a murder that could have been Johnson’s. An interview with them led him to the actual killer, but McCormick wouldn’t write about it just yet—it was to be the last chapter of another book he was planning. He spent many more hours in Mississippi, knocking on doors, asking questions on the Rolling Store, a bus that served as a shop for sharecroppers. He eventually tracked down Johnson’s two half sisters near Baltimore in 1972 and got the first known photos of the bluesman as well as first publication rights to use them and other family memorabilia. It was the find of a lifetime. Guralnick is still in awe of what McCormick did: “He never would have found Johnson had he been limited by the conventional approach. His work is a tribute to the untrammeled imagination.”

So when the two-CD Robert Johnson box set came out in 1990, the one that has sold more than 600,000 copies, why wasn’t McCormick’s name mentioned in the 48-page booklet that accompanied it—and why didn’t he, of all people, write the liner notes? No one knows for sure. (McCormick refused to talk to me about Robert Johnson.) But it has something to do with a blues fan named Steve LaVere, who located one of the half sisters in 1973, a year after McCormick did, and got her to assign to him the rights to administer Johnson’s estate. LaVere subsequently went to Columbia Records with photos and his own story about searching for Johnson, and the label committed to releasing an anthology with him as a co-producer. When McCormick heard the news, he notified Columbia about his prior deal with the half sisters, and the project was put on hold, remaining so for sixteen years.

In the meantime, McCormick worked on his book about Johnson, tentatively titled Biography of a Phantom, and he finished one of his masterworks, the album Henry Thomas, “Ragtime Texas.” Thomas was one of the grand old names McCormick had sought for The Texas Blues for decades—a mystery man who had recorded in the late twenties. Thomas’ music, like Lipscomb’s, wasn’t purely blues but lay in the DMZ between blues and the music that came before—reels, ballads, ragtime, and gospel songs from the 1880’s through the 1920’s, many with the chirping sound of those quills. If McCormick was going to write the definitive guide to the origin of the blues, he had to know where it came from, and Thomas seemed to be a guy to follow. McCormick’s interest became a mild obsession over the years, and as he did his grid searches, he asked questions about Thomas. He played Thomas’ 78’s for people, and some identified his accent as coming from northeast Texas. He got a tape of a Thomas song called “Railroadin’ Some” that listed town names along the Texas and Pacific Railroad stretching from Dallas to the hills of East Texas, and he knocked on doors along the route, talking to old-timers who remembered the colorful guitar-and-quills-playing hobo nicknamed Ragtime Texas. McCormick tracked down a second cousin living in East Dallas whose sister had a battered family Bible, and there it was: Henry Thomas, born in 1874 on a farm in Upshur County.

As the Herwin label collected the 23 songs Thomas was known to have recorded, McCormick wrote a 10,000-word evocation of the man. “That essay,” says Guralnick, “has such imaginative breadth and scholarly research. Mack went beyond the facts and reimagined the world and music of Thomas—it’s one of the most extraordinary pieces of writing on blues I’ve ever read.” McCormick not only came close to finding the source of the music but also had an epiphany of sorts that transported him back to the beginning of his career. While researching Thomas, he saw a picture and a drawing from newspaper ads, one of which looked remarkably like the tall hobo he had stopped near the train station in Houston in 1949. When the Thomas anthology finally came out, in 1975, it was clear that McCormick’s first field research had led to one of his greatest achievements.

The publication of Biography of a Phantom was announced for the following year, but no book materialized. McCormick took his research and various other manuscripts and moved to another house in Mexico to get some work done. For a decade there were rumors about the book, exacerbated by growing anticipation of the Johnson box set. In 1988 McCormick wrote in the Smithsonian’s American Visions magazine that he had promised Johnson’s killer that he wouldn’t publish until the man died. The next year, Guralnick, to whom McCormick had shown much of his research in 1976, published Searching for Robert Johnson, a book heavily indebted to his fellow historian. “My entire purpose in writing it was to announce the imminent arrival of Mack’s book and perhaps spur him on,” Guralnick says now. The gambit didn’t work, and when the box set came out, in 1990 (Columbia finally decided to go ahead with the project), McCormick was, as he had once called Johnson, something of a phantom.

Indeed, McCormick was the forgotten folklorist. He was spending his time working on various projects—articles, albums, a family history, a little fieldwork here and there—but he had alienated many in the music world (and perhaps possible benefactors of his archive) when those books never came. Some thought he was playing games or hoarding information. McCormick says he wasn’t, that he had always been addicted to field research and it just kept piling up. Also, he had a family and needed to make a living. “It was always something,” he told me. “Most of the time it was some museum or the park service calling, asking, ‘Do you want to go do this?’ ” Strachwitz, who had had a falling-out with McCormick in the mid-seventies, knew him to be a champion procrastinator. McCormick rationalized his limitations and began withdrawing. He became reclusive and hard to get hold of. His home was robbed a couple of times, which fueled his mistrust. He declared himself retired. LA Weekly writer Robert Gordon says that after he spent two weeks trying to get him to agree to an interview, McCormick finally answered the phone but claimed to be a nonexistent brother. (McCormick denies this: “I told him, as myself, I did not want to contribute.”) After a lifetime spent making connections, he was letting them go.

What no one knew was that McCormick was ill. “A great part of the reason I haven’t published anything in years,” he told me, “is I developed a manic-depressive illness. I’ll have states of grandiosity and then a short time later no energy at all. I’d get started on something and then wake up a few days later and say, ‘I don’t see the point anymore.’ It’s a crippling and destructive disease.” McCormick said that after trying twenty different antidepressants over fourteen years, he finally found the right medicine only four years ago. As for those stories of his self-imposed seclusion, he said, “People call and ask me things all the time. I’ve helped something like a thousand people. I’m not a recluse—I don’t know how I got that reputation.” When pressed, though, he admitted, “I think it’s because people know I’ve started and not finished these books.”

Indeed, the manuscripts sit where they’ve sat for years, silently goading him, especially because a few need only a good, passionate editor or co-writer to finish them. The Texas Blues, all 500,000 words of it, is 80 percent done (McCormick said it grew far beyond being merely a blues book long ago, expanding through the years to include all Texas music), and The Aggressive Birth of the Blues is researched, with maps, fieldwork, and interviews—it just needs to be written. (All McCormick will say about the Robert Johnson manuscript is that it has been abandoned: “It ain’t happening anymore. I lost interest.”) If these works were completed, they would be the most anticipated music books in years and McCormick’s reputation as a hermit would be moot.

At an age when most people are retired, McCormick is still addicted to research, still adding to the Monster, still in love with the chase. Lately he has been mildly obsessed with Emily Dickinson, another semi-recluse, whose life he’s probing for a play he’s writing. “She’s so inspiring,” he said. “All I have to do is go to one of her poems for hope. ‘This is my letter to the World’ is the most heartbreaking poem and the closest to my own lonely feeling sometimes.” That feeling got him to join a support group for manic-depressives: “I tell people who are suicidal, who call at three a.m., ‘Of course it’s hopeless. Who told you it was any different? It’s only hopeful in those few moments when you’re delusional.’ ”

But McCormick’s life belies such playful cynicism. Only a believer, a person with hope, would spend so much of his life knocking on doors, talking to strangers, seeking connections, even if they sometimes seemed to last for just a few moments, like when Joe Patterson played a jumble of sound on some reeds bound together by white hospital tape.