In my mother’s house, a lonely picture used to hang over the piano. In it, a man stood alone in an unfurnished room, his arms reaching toward the heavens. Before him sat an old-school radio. He had broad shoulders and a long, lean body; in his right hand, he held a conductor’s baton. I could only see his back, but I imagined a thousand times what expression his face might have held. I was only a witness, but something in the art said that it saw me as much as I saw it—and that somehow a transference of power was taking place, as if seeing his Brown body command sound to bend in his direction gave me permission, too.

This same power pulses through every piece in “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power,” a new exhibition on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH). With pieces crafted by more than sixty artists, the exhibition spans two revolutionary decades of American history. Not only does it explore what it meant to be a Black artist in the tumultuous era of the sixties through the eighties, but it also depicts the grace and strength carried within one’s skin when existing is its own act of resistance. From sculpture to black-light art, the show captures visual artists exploring survival and political unrest within the country that they simultaneously called home.

The internationally acclaimed exhibition, organized by Tate Modern in London, was slated to open at the MFAH in April but was delayed because of the pandemic. “Soul of a Nation” is now on view in Houston through August 30 as the final presentation of the three-year tour. Houston will serve as its fitting end, as an especially diverse city and one whose own artists became a vital part of the exhibition. An audio tour of this exhibit and virtual events, including artist talks, discussions, films, and more, are available on the MFAH website, along with tickets for socially distanced visitations. (Visitation protocols are also available online.)

As the installation makes plain, Black American artists are caught between two realities. In one, they seek to claim home with the only land they have known. In the other, they know that this blood-soaked land does not safely love them in return. So they make the choice to love themselves in the process. This choice can be seen clearly in the welded steel sculpture Some Bright Morning, by Houston native Melvin Eugene Edwards. While the title heralds hope of a better tomorrow, this first piece of Edwards’s Lynch Fragments series centers around the horrors and the physically oppressive nature of slavery in America. Metal chains and harvesting blades are trapped in stasis, posing a present and immediate threat, while still offering some hope that their archaic nature will somehow become extinct.

It is this hope that drives the entire exhibit. From Texas-born Kermit Oliver’s poignant Yellow Dress to John Biggers’s vibrant documentation of his travels to Ghana, Benin, and Nigeria in 1957, in The Stream Crosses the Path, the installation depicts how Black artists attempt to reconcile a conflicting being that experiences daily suffering while clinging to a richly distant and elusive past. This in and of itself is its own act of reclamation. When artists capture Blackness in art, they are telling the whole world that no amount of oppression can stop them from being worthy of love. That nothing can withhold the world from seeing us. They are proving that we are here, and that we always have been. They are reminding us that joy is waiting every day to greet us, right alongside suppression.

There is power on focusing a lens on a single clenched fist when the chaos of living pulls you toward the cliff of fear. The work doesn’t seem to hide that, and rather feeds on it, as in David Hammons’s screen print Black First, America Second. In the piece, two Black bodies entangle themselves in the fold of a flag. This ultimate symbol of patriotism becomes a vulnerable declaration that America belongs to the Black body as much as to any other person. However, as a people who have often found ourselves searching for our own identity in a forgotten past, we must acknowledge the bondage in order to truly celebrate freedom. This fine balance makes it imperative that works like Frank Bowling’s Middle Passage sit alongside rallying calls like Reginald Adolphus Gammon’s acrylic Freedom Now. This act of juxtaposing how the world has been remapped by our persecution is the rebellious work necessary in art from Black hands. And this is not easy work, for the artist or for the witness.

Work like Betye Saar’s Eye, from 1972, an oversized eye made from leather and acrylic, does not allow the witness to dismiss Black art as merely an entertaining experience. Rather, it holds us in its gaze and makes us the exhibit. In that, we must examine how the world sees us in all of our biases and assumptions. And this is also its power. Where else but in art does the Black creator have enough silence to speak without being interrupted? The witnesses are collectors of this evidence of living, and this kind of work extends every Black artist’s life into immortality.

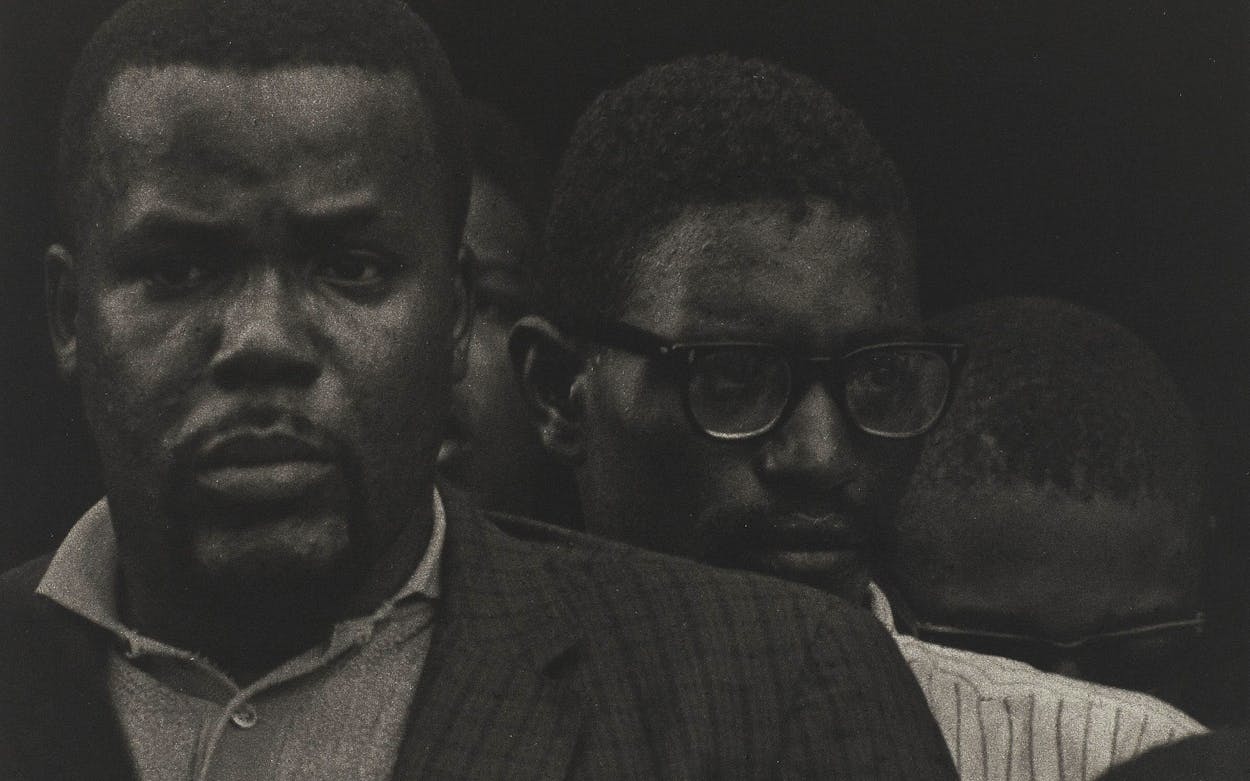

I have carried this notion since my mother’s living room: the idea that Black art does more than adorn our walls, that it also serves as a point of documentation of the ways that history has tried to erase us. It reclaims our narrative. Pieces like Roy DeCarava’s photogravure Four Men, New York 1956, which depicts four male Yates students, hark back to the beauty of the everyday. They remind us that humanity supersedes fear. We stare into these young, unnamed men’s faces and see our sons and brothers. We watch as their faces stare into ours, knowing what dangers await them in just existing in America. This is how empathy arises. This hook lodges itself in the heart and forces us to look them and finally see who they are. And we cannot turn away from that.

As a Black woman, I need that kind of reminder, especially given our recent political climate. As images of public hangings and viral deaths haunt our virtual timelines, it sometimes becomes hard to see another side. It is then that the art reminds me.

Whether it is a large coffee-table book of brilliant Black faces in I Dream a World or a limited edition print of Edwin Lester’s Restoration hanging outside my office, or an exhibition in the fine arts institution in the city I live in, I am able to remind myself daily that all that has been done to us has only chiseled strength into our mahogany fists. That we saw no way out before, and these stunning pieces of art still live on to tell how we moved forward, and continue to. That there are artists who show the world that we are beautifully human. And that every time I look up, there is a world bending to the tip of a paintbrush, or pen, or conductor’s baton, a reminder that I have the power to see and reshape things for myself.

- More About:

- Art

- Black Lives Matter

- Houston