While sitting in a parked car in Marfa last September, the musicians Miranda Lambert, Jack Ingram, and Jon Randall listened to their “work tapes”—what songwriters call raw recordings they typically make just after finishing a song. These iPhone recordings documented the trio of Texas natives’ four trips over seven years to West Texas, where they occasionally held loose songwriting sessions. Lambert had already turned two of them into hits—2019’s “Tequila Does” and the Academy of Country Music’s 2018 Song of the Year, “Tin Man.”

But relistening to their tapes that fall night, it occurred to Lambert that most of the trio’s work wasn’t likely to reach any listeners. So she proposed they record slightly better versions of the songs and release them as an album. “That was probably the Tito’s talking,” Lambert says. “But the next morning, in the sober light of day, it still felt like a legitimate idea.”

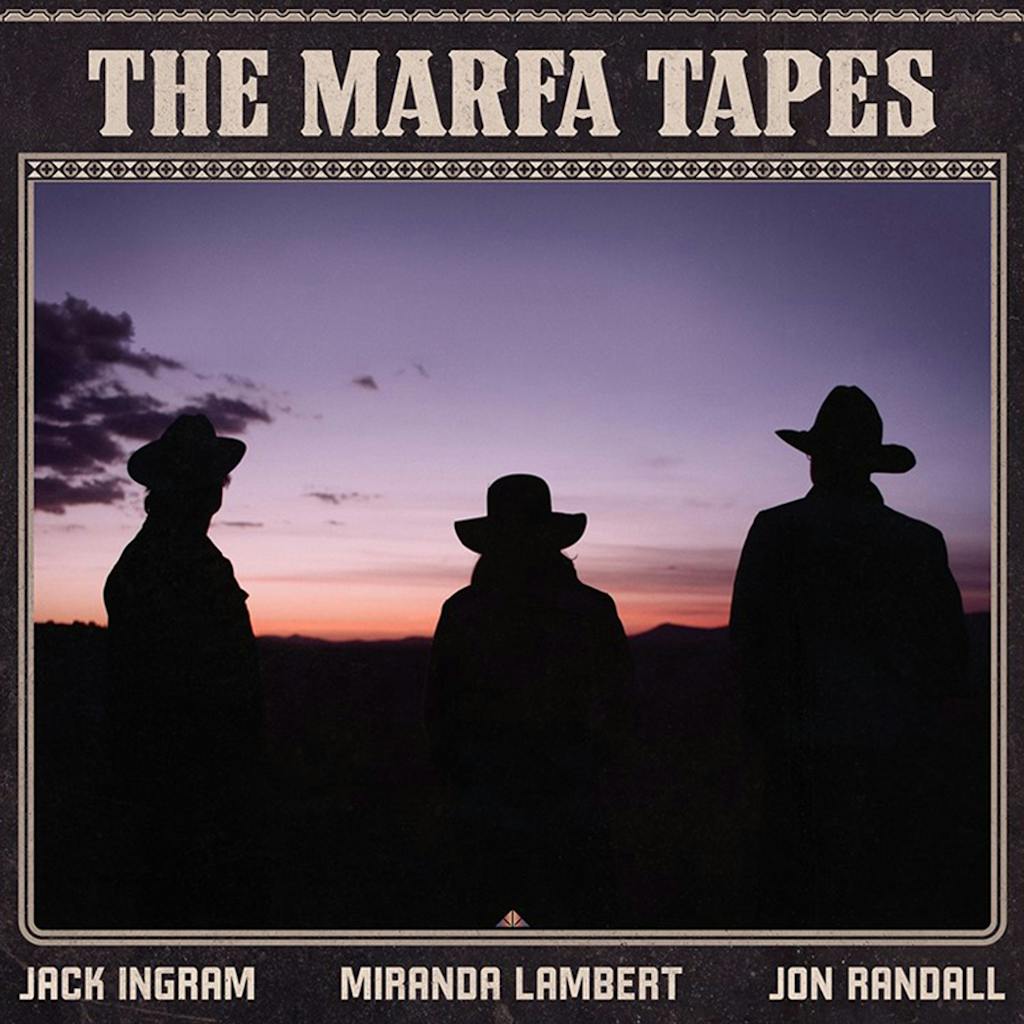

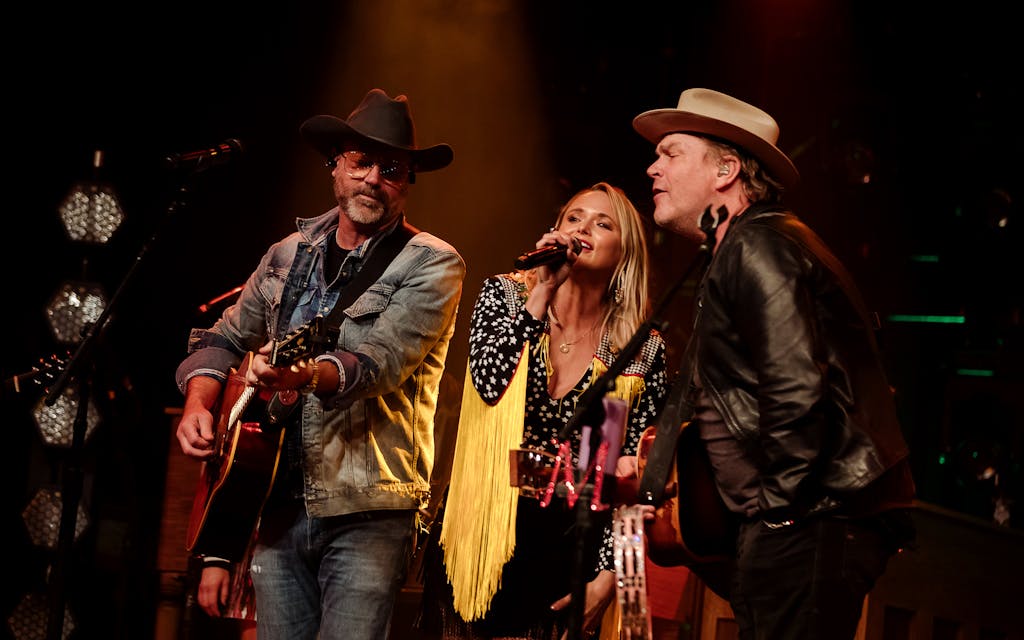

A few months later, they returned to Marfa to record what they’d wind up calling The Marfa Tapes, out May 7 on Vanner Records/RCA Nashville. The low-key campfire setup—which involved a pair of microphones and an acoustic guitar—was a departure for three musicians accustomed to proper studios and generous budgets. Ingram, a pioneer of the late-nineties “Texas country” scene, made his national debut in 1997 and has released seven albums since. Randall, who began his career as a guitarist for Emmylou Harris’s Nash Ramblers and went on to record four solo albums, is best known as a producer for the likes of Dierks Bentley and Dwight Yoakam.

Lambert says the trio immediately agreed that the songs called for atmosphere, not sheen, and they recorded virtually everything on its first take. Listening to the album, you can hear desert wind bleeding through the mixes, along with plenty of laughter, and a handful of flubbed lyrics. Aside from new versions of “Tequila Does” and “Tin Man,” the rest of the album’s fifteen songs haven’t been heard outside of Marfa. More than a few tunes, including “Am I Right or Amarillo,” “Waxahachie,” and “Two-Step Down to Texas,” unapologetically focus on Texas. “That’s not on purpose or something we purposefully avoided. We’re three Texans who got to come back home,” Lambert says. “And I love that it feels like home and sounds like home.”

Ahead of the album’s release, Lambert and Randall spoke to Texas Monthly by phone from Nashville.

Texas Monthly: Guy Clark once asked Rodney Crowell, “Do you want to be a star or an artist?” This seems like the kind of record you make because you’re an artist and get to release because you’re a star, and one that not a lot of stars would bother to make. Does that sound right?

Miranda Lambert: Yes. I haven’t thought about it like that, but I guess all the years of work put in by all three of us allowed us to do this because we love it, without having to apologize. And I also attribute a little bit of that to the time that we chose to record this, [during] the pandemic. There was room and space to go do it without thinking about schedules, touring, and the other projects we have going.

TM: On those first three or four trips to Marfa, what expectations did you have to come out with songs that might work for your records?

ML: I try not to have too much expectation because I have let myself down too often. But there’s certainly something special about the three of us together, Marfa and what comes out of that. We all had this innate sense that it wasn’t just a regular hanging-out songwriting session. It felt substantial.

Jon Randall: The first trip came at a desperate, crazy time. And it was a therapy trip for everyone. Initially, the expectations were just three friends running off to West Texas to hide out and maybe write some songs. And we ended up writing seven songs that trip. Everybody was going through different things, and we were all just kind of finding our way through it. The next trip was, “Wow, how fast can we get back to Marfa and hang out again?”

TM: Beyoncé was there almost ten years ago and we didn’t find out until weeks later when she posted a picture on Instagram. It’s not a place where people care about celebrity.

ML: They don’t care. You’re right. I was having a really bad year that year that we went the first time. There was fake news everywhere. And we went to the grocery store and Jon pointed to the magazine rack, which was completely empty. And he says, “Well, that works.” I was in the right place. And I think the songs came in like they do because there’s no other worries. There’s no other stressors. You’re just out there, like on another planet.

TM: Miranda, it seems like you’ve built a career on having a sense of self that’s baked in. Jack told me the best part of writing with you is that you know exactly who you are and what you’re willing and unwilling to do and say.

ML: I like the term “baked in,” because that’s what it feels like. I know what I can bring, but my abilities only go so far and only take me so many places, so I try to find people that blow my mind every time they say a line or play a lick. And two of those people are Jack and Jon. None of us shows up to write together with a half-ass attitude about it. If we’re going to do it, even if we’re drinking and having fun, we have such a level of respect for each other that we bring our A-game, even in those moments.

JR: I’ll say this about Miranda too. I have spent thirty years on and off working with Emmylou Harris. And Miranda reminds me a lot of Emmy in that they both love to lift up people around them. Emmy finds something that she loves musically or finds a guitar player and feels like it makes her better to have all this great talent around her. Miranda does the same for people that she loves. And she just wants to collaborate and make great music. Even though she’s got this amazing celebrity solo career, she’s such an artist and musician, her heart wants her to take these chances and do these things. I’m just lucky to get to ride along with her and Jack for that part of it.

TM: You both moved from Texas to Nashville at around the same time in life, basically right out of high school. Yet you sound decidedly, unmistakably, like products of Texas.

JR: I moved to Nashville in 1987 for the bluegrass scene. That was my thing. And then when I got here, I started hanging out at bars where Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt were playing. At that time in Nashville, they were allowing hippie poets to hang out. [Kris] Kristofferson was one of those guys. And so for me, I went for one thing, but wound up kind of following my heroes around. And you never leave Texas. It goes where you go.

ML: That’s so real and so true. I was playing in the bars in Texas and loving it. Every second of it. I was like seventeen or eighteen years old, traveling around in my mom’s Expedition or motor home, trying to get my name out there and get some experience. I wanted to make sure that I was dreaming as big as I possibly could. And growing up, coming up to Nashville for Fan Fair every year and loving all kinds of country music, I wanted to make sure that I explore that. I also know this about Texas: if you’re from there and you make music, you’re welcome back any time.

TM: But when you arrived in Nashville, Jack and Pat Green, Bruce and Charlie Robison all had recently made records there and wound up back in Texas after runs that didn’t quite meet Nashville’s commercial expectations. From a business perspective, was there any temptation to play down the Texas thing so they wouldn’t lump you in with that?

ML: I think they taught me a lot because all those guys you mentioned are heroes of mine. They’re what I grew up on. That’s who I saw live every weekend and tried to open for. But in Texas back then there was also this “we don’t need Nashville” mentality. And I loved Nashville. And I loved Texas, too. I was inspired by music coming out of both places. And so I just wanted to make sure to not get caught up in that. I didn’t understand why Texans at that time were so anti-Nashville. And I get there and ended up being on a show called Nashville Star and Charlie was a judge. It was all so weird to me. It’s like, “What’s the right answer here?” But I just stuck with my gut. I still had my Texas sound and I used Frank Liddell to produce, who’d made a bunch of records for the Texans I loved. And so I got to do the best of both.

TM: How much is this campfire folk singer thing you do here also a bit of an evolutionary step for you? Is this your next phase?

ML: It feels more like me than anything else I do, to be honest. And that’s how I grew up. I’ve evolved so much as an artist from seventeen to now that I have lived a lot of story, but I’ve always been a songwriter first. And I’m a campfire singer-songwriter at heart. I don’t know what kind of doors this is going to open. I hope it opens doors for volumes two and three. Because if people love it and respond, then we keep doing it.

TM: You intentionally wrote with women for a while, almost exclusively. How is it different being with these two?

ML: The Pistol Annies are my other power trio, and that has its own vibe too. Different vibe, you know? But I’m a tomboy. I hang with the guys pretty good. So I feel at home either way. Nobody loves a girl power song more than I do, but I also love writing those songs with guys, especially these two, because they will go there with me.

TM: Jon, the opening lines of the last song on the record are “Out in West Texas, it hardly rains / When it does, it’s amazing grace.” When you craft a line like that, what’s that feel like?

JR: It feels like you’re onto a good idea and you better go ask Jack and Miranda to help you finish it, because I don’t want to screw this up.

TM: But in all seriousness, that’s the moment this is all supposed to be about.

JR: Right. And that’s one of those songs where it captures something that was happening. Nobody was digging in their soul or pulling up skeletons and digging up bones. It was a magical and honest moment.

TM: It’s obviously a different moment than standing in front of 30,000 people, but when you write a line that lands, something particularly insightful or clever, I suspect that “eureka” moment feels similar?

ML: It’s the same feeling. Being in an arena playing “Tin Man” with everybody singing it back at you is an incredible feeling. But I had the same feeling when we finished the last line of that song, you know? I’ll never forget one of the standout memories of our trips in Marfa, when we were writing a song called “Ghosts.” We kind of wrote ourselves into the corner and everyone was staring at each other. And it just came out. I said, “I’m not afraid of ghosts.” Jack celebrated by running around the campfire as fast as he could. We’d all wrote so hard on this song and then none of us could figure out where the hell to go next. And suddenly it’s there. It’s just exhilarating.

TM: When you’re singing “Tin Man” in an arena, in your head are you visualizing the process? Do you think about Marfa?

ML: I do. And I especially do when I started doing “Tequila.” That whole lyric and that feeling just puts me right back there. And that’s another reason I’m glad we have this project, in that we could take people with us there if they hadn’t gone or can’t go. I feel like it takes them with us, and taking people somewhere else is what I try to do every night on stage. I get to take them home to Texas.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

- More About:

- Music

- Miranda Lambert

- Marfa