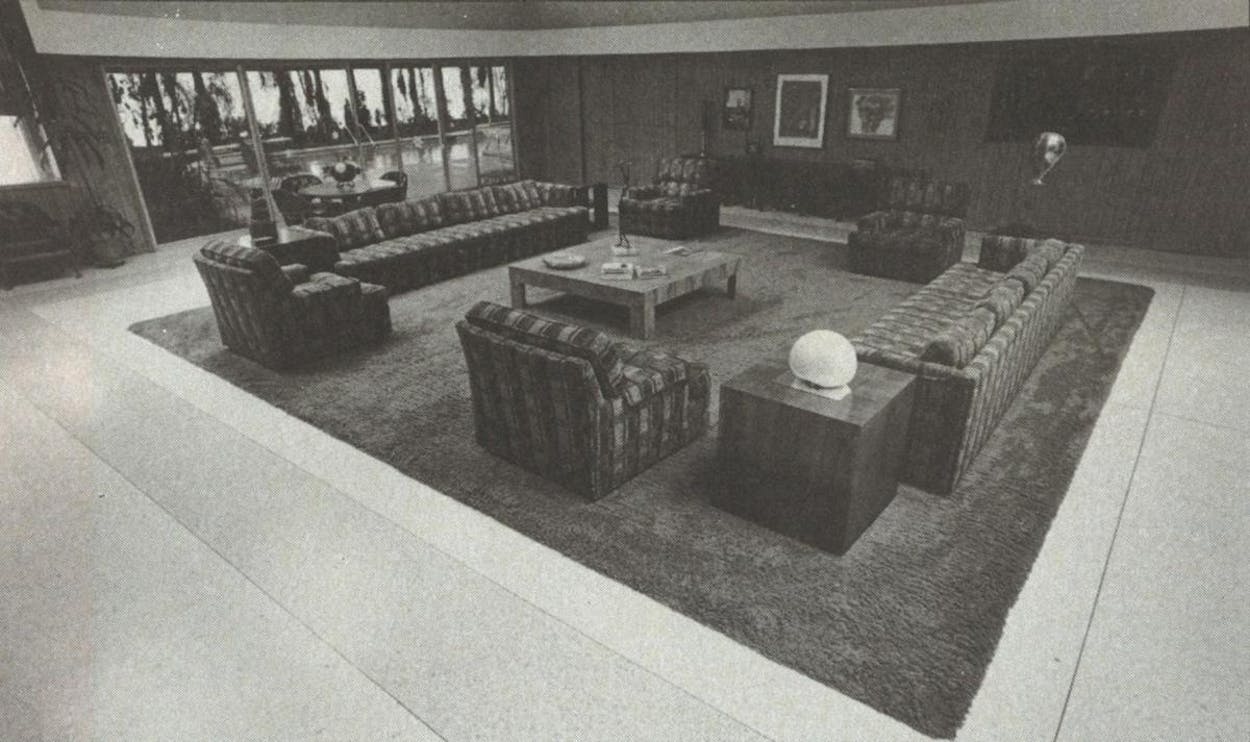

It’s not so much the $2.75 million price tag that has Dallas real estate circles twittering about the Shanbaum house on Inwood Road. And it’s not that the flagstone ranch house looks radically different from any number of lumbering, low-slung mansions in this megabucks neighborhood. What nobody can get over is the size of the place. At more than 28,000 square feet it could be the biggest house in Texas, large enough to condo into twenty 1400-square-foot units. My entire forties bungalow would fit into the largest of the Shanbaums’ three living rooms.

More astounding still, Casa Shanbaum flies smack in the face of the traditional American nuclear-family dwelling. It’s really two enormous houses connected by a set of sliding glass doors. Make that two and a half houses. The second wing, started four years after the original 1964 wing, contains a complete upstairs apartment. Along with the three kitchens and three dining rooms and nine bedrooms and two dens and kids’ playroom and barbershop and sauna and exercise room and massage room and office suite and his-and-hers dressing rooms and countless closets and outdoor pool and cabanas (you practically have to pack along a lunch if you plan to see it all), the purchaser will get a heated indoor pool enclosed by a two-story atrium. That’ll put him one up on neighbor Ross Perot, who has no indoor pool to call his own. Neither can Perot boast such a battalion of bathrooms. They number either sixteen and a half (according to the official Ellen Terry Realtors brochure) or nineteen (according to Ted Shanbaum, who begat the residence).

Now, some people, contemplating the Shanbaum abode, might ask, “Why?” Theodore B. Shanbaum, who hit Dallas during the Depression with $300 in his pocket and parlayed it into the nineteen-state Lee Optical empire, asked, “Why not?” Shanbaum grew up on the fourth floor of a Chicago tenement in company with parents, five siblings, and five other families. There was one bathroom for the whole floor, and according to the ebullient, talkative Shanbaum, “There was always a line.” One day he felt sick. His mother administered a dose of castor oil. When nature called, Shanbaum ran to the washroom, only to find it occupied. His mother marched him out to the stoop, pulled down his trousers, and indicated the back yard four stories below. Later, Shanbaum resolved that if he was ever in a position to build his own home, “there would be a washroom within five feet no matter where I sat in that house.”

Ted got his washrooms and a lot more besides. What he wrought on Inwood was nothing less than the house the Jock Ewing should have lived in: a fiesta of fabrics, a circus of surfaces, a whopping aggregation of sixties and seventies artifacts. It’s an unpretentious place that the goat-cheese-and-Architectural-Digest crowd would never go for, but the house has an innocent exuberance; it expresses the old-fashioned Texas ideal of comfort and expansiveness rather than sophistication. The color scheme runs to lime greens, blues, aquas, golds, and lots of sensible browns. In accordance with that deepest of erstwhile-poor-boy impulses, there is seldom one of anything where two will do—two costly Sub-Zero refrigerators in each kitchen, two ovens, two dishwashers, two garbage disposals in two sinks. There have been as many as 27 television sets on the premises.

As for those multiple living quarters that Dallasites love to speculate about, Shanbaum—who built wing number two over the protests of his immediate family—explains, “We always had big families on both sides, so when there were parties or marriages or bar mitzvahs, they all would stay with us instead of having to stay in a hotel.” He says he wanted to be able to provide a home for his three sisters and his father, should they ever want to live with him. It didn’t work out that way. The Shanbaums often used all that space to play host to the Dallas Jewish community; during the Yom Kippur War in 1973, says Ted, they raised $8 million from 150 people at one Sunday breakfast. Then there were the three Shanbaum children. Whether they were busy at Hockaday, St. Mark’s, Wellesley, Colorado, or Wesleyan, Shanbaum figured “they’d always come home because they had the pleasures of the house. There was no need to go to a nightclub or a resort.” On any given weekend, there might be ten kids staying overnight. Shanbaum’s daughter and son-in-law lived briefly in the second wing while waiting for their own house to be built. But the extended family that Shanbaum envisioned on Inwood Road did not come to pass as any student of American culture could have predicted. Now the Shanbaums have scattered, and the house is on the block. “It breaks my heart not to be in a position to keep it,” Ted says. “That house smiled. I even planned the doors big enough so when I died, we could have the services there.” In the fifteen months the house has been listed with real estate agent Betty Godwin, there have been nibbles from an Iranian and a Thai (both from cultures where extended-family compounds are more the norm than they are in Dallas). A film production company made inquiries. “It will take a very special buyer,” understates Godwin, who is currently touting the house as a “corporate retreat.”

Should that special someone fail to show, perhaps Dallas might want to float a bond issue to establish the house as a museum of the sixties and seventies—just about the only era remaining unpillaged by collectors and connoisseurs. Of course, the place will lose some of its resonance without the hundreds of Shanbaum family photographs—a capsule history of fashion and hairstyles in those decades. Still, the first Jacuzzi that was ever built into an indoor swimming pool in Dallas is on the premises, along with furniture, fixtures, gadgetry, and objets d’art that embrace the entire design vocabulary of the period. If any of our descendants ever want to see real cypress, Formica, smoked mirror glass, birch, oak, metallic wallpaper, parquet, cedar, Arizona flagstone, faux bamboo, bronze mirror, gold tile, walnut, linoleum, and marble, why, there it will be. Dallas, the ball’s in your court.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Fashion

- Architecture

- Dallas