Beginning on December 31, 1884, Austin was the setting for a killing spree unlike any ever before seen in American history.

Over the course of a year, seven female residents, along with the boyfriend of one of the victims, were attacked with knives, axes, bricks, or iron rods. Police officers were baffled. They took bloodhounds to the scenes of each murder, but the dogs could find no trails. Private detectives were hired to conduct their own investigations, but they too failed to find any leads.

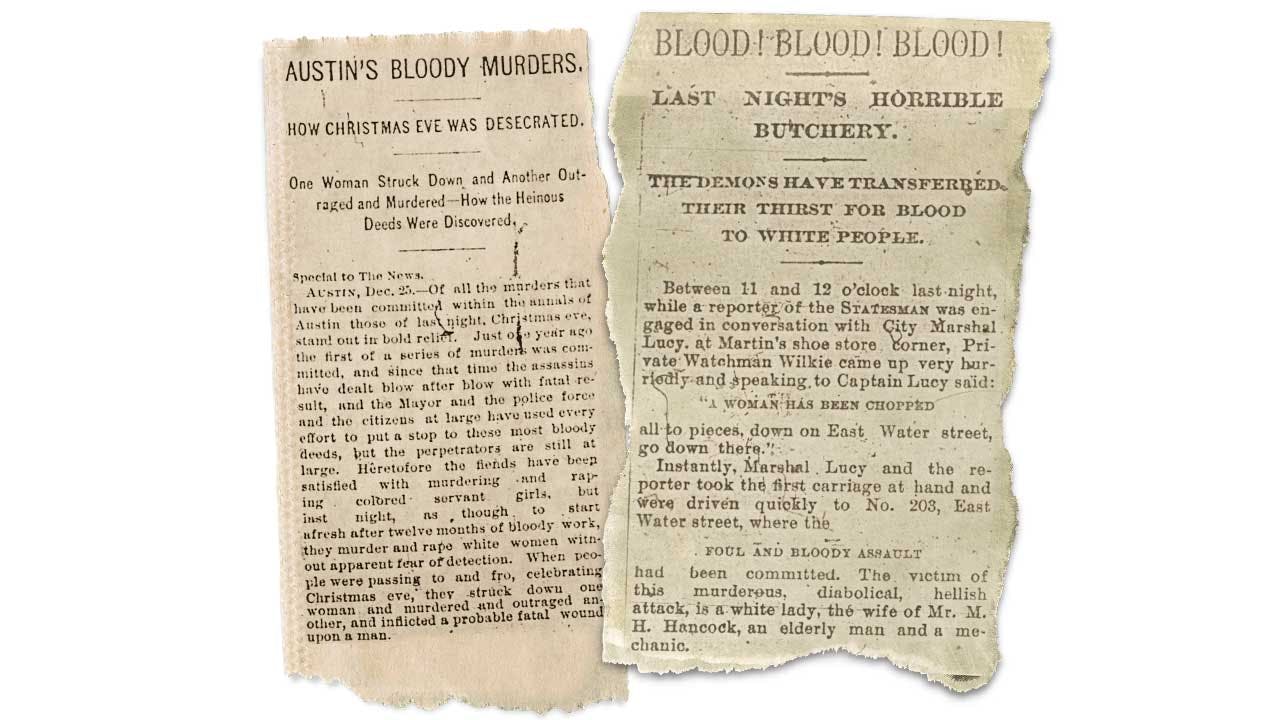

Because the first victims were black, Austin’s white residents initially believed that what was taking place was a “Negro problem.” Some city leaders theorized that a “gang” of depraved black men was committing the crimes, going after black women for reasons of its own.

But then came Christmas Eve 1885.

That afternoon, the wooden sidewalks along the downtown streets were packed with shoppers. Store owners had decorated their windows with ornaments, red and green crepe paper, and heaps of pine boughs. One merchant had placed a string of incandescent bulbs around his window, which featured a stuffed Santa Claus and tiny elves surrounded by fake snow, and another had filled his window with children’s presents: dolls, hobbyhorses, baseballs and bats, tea sets, and cowboy boots. In front of Stacy and Baker’s newsstand and tobacco shop, one of Austin’s portlier citizens dressed up as Santa Claus and sat on a large chair, where he asked the children who came to see him if they had been good that year, and at a livery stable just off Congress Avenue, Osborn Weed offered the city’s children rides on Tom Thumb, his gentle Shetland pony.

Throughout the afternoon, customers lined up at Bill Johnson’s market to buy meats for their Christmas Eve dinners, the counters loaded with steaks, hams, turkeys, venison, and some of the last buffalo meat left in Texas. Others visited Prade’s ice-cream parlor, where clerks were selling Christmas fruit baskets, ornamented cakes, and French candy for twenty cents a pound. Men drove their wagons to Radam’s Horticultural Emporium to buy Yule trees to carry back to their homes for their children to decorate. One man pulled up in his wagon at H. H. Hazzard’s music shop to purchase a piano.

As the sun began to set, Henry Stamps, the city’s lamplighter, performed his usual role of lighting the gas lamps along Congress Avenue and Pecan Street, the city’s two main boulevards. The owners of the restaurants and saloons turned on their incandescent lights. Children from the Asylum for the Blind held a concert, performing a popular new song about Santa Claus coming to town, and children at the Texas Deaf and Dumb Asylum stood around a Christmas tree decorated with candy and popcorn, making what one reporter said were “mute testimonials of affection.” There was even a Christmas party at the State Lunatic Asylum, north of the city. Dr. Ashley Denton, the superintendent, had arranged for selected patients to gather in the main dayroom, sing Christmas carols, and stay up one hour past their usual nine o’clock curfew.

An hour passed, and then another. The shop and restaurant owners turned off their lights, locked their doors, and headed home. Throughout the city, families ate their Christmas Eve dinners and decorated their trees, covering the branches with ornaments, strings of popcorn, candy-filled paper cornucopias, candles, and Japanese lanterns.

Eventually, parents let the fires die out in their fireplaces, telling their excited children that they didn’t want Santa to burn himself on his way down the chimney. A thin breeze swept through the city, carrying with it the aroma of evergreen and cinnamon and wood smoke. Soon, the moon rose. The stars appeared. According to what a reporter for the Austin Daily Statesman would later write, the moon and the stars “were at their most effulgent and shot their mellow light over all the earth and in nearly every crevice of our houses and garden fences.”

At midnight, the clock above city hall began to chime. City marshal James Lucy; his sergeant, John Chenneville; and some other police officers remained on the downtown streets, keeping watch. A couple of officers checked the saloons to see if any suspicious characters were drinking at the back tables; another group of officers walked the alleys behind the downtown buildings, looking for tramps; and a couple more wandered through Guy Town, the city’s vice district, to make sure the men at the brothels were behaving themselves.

Suddenly, there were hoofbeats. A horse was seen coming straight up Congress Avenue from south of downtown, and it was coming fast, whipping through the cones of light thrown out by the gas lamps. On the back of the horse was a man named Alexander Wilkie, a night watchman at one of the saloons.

“A woman has been chopped to pieces!” Wilkie yelled. “It’s Mrs. Hancock! On Water Street!”

Susan Hancock was the 45-year-old wife of Moses Hancock, a prosperous carpenter, and the mother of two daughters. Friends described her as “one of the most refined ladies in Austin,” a “handsome woman” who “bore an unblemished character” and was a “tender mother” and “devoted wife.” She was also white.

The police officers leaped on their horses and raced to the Hancocks’ home, which was at the southern end of downtown, just a block away from the Colorado River. Those who didn’t have horses simply began running toward the house. They ran so hard that their stomachs heaved and their breath tore at their throats. Marshal Lucy and a Daily Statesman reporter, who happened to be standing together outside of Martin’s Shoes and Boots on Congress Avenue, piled into a hack. It barreled down the avenue, rocking back and forth like an old stagecoach.

Lucy found Moses in the parlor of his one-story home. He was dressed in his long underwear, which was stained with blood. On the floor of the parlor, lying on a quilt, was his wife. There were two deep wounds in her head—the result of ax blows. One had cut into the cheekbone. The other, which was between her left eye and ear, had perforated her skull and sunk into her brain. Her right ear also had been punctured by some sort of rod.

Susan was breathing erratically. According to the Daily Statesman reporter who had taken the hack to the house with Lucy, “cupfuls of blood” were pouring from her mouth. From a back bedroom could be heard the desperate cries of the Hancocks’ daughters, one 15 years old, the other 11. In what would later be described as a “distracted, disconnected narration,” the 55-year-old Moses, who was leaning against a wall of the parlor, told Lucy that his wife had spent the afternoon shopping. After she returned home, the two Hancock daughters had gone to a Christmas party, escorted by a boarder staying in their home. Hancock said he and his wife had sat by the fireplace, reading and sharing a piece of cake. They had gone to bed between ten and eleven o’clock, before the girls had returned home from the party, and they slept, as they always did, in adjoining rooms. A gas lamp had been left burning by the front door.

Just before midnight, Hancock was awakened by a noise. He walked into his wife’s room and saw that her sheets and bedspread were piled in a heap on the floor. Her trunks were open and her clothes pulled out. The window of her room, facing the backyard, was also open, and blood was on the windowsill.

Hancock said he walked out to the yard, where he found his wife lying in a pool of blood. As he bent over her, he heard a noise near the back fence. He turned and saw a shadowy figure wearing dark clothes. The man—Hancock could not provide a description—quickly jumped over the fence and ran down the alley. Hancock started yelling, grabbed a brick, and threw it at the man. His next-door neighbor, a brickmason named Harvey Persinger, came into the yard and helped Hancock lift his wife from the ground and carry her into the parlor. Then Persinger ran for help. He found Wilkie, the night watchman, who rode up Congress Avenue, crying out the news of the attack.

Dr. William Burt, the physician from the City-County Hospital, quickly arrived at the Hancocks’ home, as did another physician. They worked feverishly to save Susan’s life, pressing bandages over her wounds to stop the bleeding, giving her a shot of morphine, and pouring a little brandy into her mouth to see if she would swallow it. She couldn’t. In the gaslight, the blood over her skin had an almost glossy sheen.

More men showed up at the Hancocks’, including Mayor John Robertson, who had been alerted by telephone. Some of the men struck matches to their oil lamps, adjusted the flames to the highest possible height, and held the lamps above them, trying to cast as much light as possible into the backyard’s shadows. Dr. Burt’s teenage son, who had accompanied his father to the Hancocks’, spotted a bloodied ax three feet from the window of Susan’s bedroom. When Moses was shown the ax, he said it belonged to him and that he kept it on top of the woodpile by the back fence.

Finally, a police officer showed up with Sergeant Chenneville’s bloodhounds. The dogs sniffed the ax, the woodpile, and the spot in the yard where Susan had been found. But because so many men had already tromped through the yard, the bloodhounds could not find any tracks to follow. They were led out to the alley, where they began running westward, alongside the Colorado River. A group of officers chased after them. They slid their six-shooters out of their holsters, but they came across no one. Minutes later, the dogs lost whatever trail they were following.

Back at the Hancocks’, the men kept waving their lamps over the backyard. Then, in the distance, they heard more hoofbeats.

Henry Brown, the night clerk at the police department, was on his horse, coming at a full gallop straight for the Hancock residence. When he saw Marshal Lucy, he began yelling that a woman had been found on Hickory Street, on the northwest side of downtown, two blocks from city hall.

Lucy and the other men in the yard stared at him.

“It’s Eula Phillips!” Brown shouted. “Her head’s been chopped in two!”

The men kept staring at him. Eula was the seventeen-year-old wife of Jimmy Phillips, who was the son of a successful Austin architect and home builder. Slim as a fawn, barely one hundred pounds in weight, Eula was regarded as one of Austin’s most beautiful young women, with eyes the color of maple syrup, a delicately cut chin, a bewitching Mona Lisa–like smile, and auburn hair that bunched in curls on the nape of her neck. Whenever she walked the sidewalks of Congress Avenue, she was stylishly dressed, wearing broad hats heaped with feathers and tight crinoline dresses, underneath which were wiggling bustles and corsets that pushed up her bosom.

“It’s Eula Phillips!” Brown cried again.

Men began jumping on horses or piling into hacks and racing back up Congress Avenue. They made a left turn at city hall and headed for the Phillipses’ residence. Whips could be heard cracking against the horses’ flanks. Chenneville’s bloodhounds also sprinted up the avenue, baying all the way.

The home was one of the city’s finer residences. Lucy and the other men were led to the backyard and taken to the outhouse. Next to it was Eula, her nightgown pulled up to her neck and her hair rolled in brown curling paper. She was on her back, the blood around her “warm and scarcely coagulated,” a reporter would later write. She had been struck directly above the nose by the blade of an ax: a perfect vertical blow, splitting her forehead wide open. There was another horizontal cut across the side of her head. Because her nightgown was tightly twisted around her neck, the police speculated the killer had used it like a rope to drag Eula across the yard.

And there was something new about this murder scene: three small pieces of firewood had been placed, almost ceremoniously, on Eula’s body—two across the breast and one across her stomach. Her arms had been outstretched. It was as if she had been posed to look like a figure in a crucifixion scene.

Lucy went inside the house and was directed to the room—in a back wing of the house, at the end of a long hallway—where Eula, Jimmy, and their eighteen-month-old toddler, Tommy, stayed. Jimmy was still in bed. There was a large gash above his ear. The Phillipses’ family doctor, Joseph Cummings, was already there, pressing a pillow against the wound. A bloody ax was at the foot of the bed.

Jimmy seemed to be in a stupor. His mother, Sophie, told Lucy that at some time after midnight, she heard Tommy crying. She walked into Jimmy and Eula’s room and almost fainted when she saw Jimmy curled up in bed under bloody sheets and the baby sitting up, holding an apple, unharmed even though his nightclothes were crimson with blood.

Sophie said she ran back to the master bedroom to alert her husband, James. Using Jimmy’s nickname, she shouted, “Bud is knocked in the head and Eula is gone!” James ran outside and, with the help of other men in the neighborhood, eventually found Eula. One of the neighbors then ran over to city hall and took the stairs up to the police department to alert the night clerk.

After Lucy finished speaking to Sophie, he was shown a bloody footprint on the wooden floor in the hallway outside Jimmy and Eula’s room, right next to a door leading to the backyard. He ordered that the planks containing the footprint be cut from the floor and taken to the police department. He also ordered that the ax in the bedroom—which James had identified as his, saying he had last seen it on top of his woodpile behind the house—be taken to the police department and placed next to the ax found at the Hancocks’.

Meanwhile, in the backyard, someone spotted drops of blood on the top rail of the back fence. Chenneville’s dogs were led into the alley, and they headed off into the darkness, the sound of their baying echoing against the other houses. But soon they again came to a baffled stop. It was as if the scent—if there had been a scent—had simply vanished.

Within minutes, the news was spreading over the telephone party lines. Susan Hancock and Eula Phillips had been found in their backyards. Someone was now targeting white women.

Grabbing their rifles and tearing open boxes of shells, some men shouted at their families to get out of their beds and gather in one room. They stood in front of their families, the grips of their rifles cold in their hands, waiting to see if whoever was out there was going to come after them. Other men decided it was far safer to get their families out of their homes. They loaded their wives and children onto carriages or wagons and raced toward downtown.

It wasn’t long before several hundred people were packed on Congress Avenue, standing under the gas lamps. A reporter who worked as a freelancer for the Western Associated Press ran to the Western Union office, grabbed a clean sheet of white paper, and drafted a telegram to send to his St. Louis office. “The entire population is in the streets, excitedly conversing,” his telegram began. Right behind him came the Austin-based reporter for the Fort Worth Gazette. “People tonight are in a state bordering on frenzy,” he wrote. “Groups of excited men parade Congress Avenue and ask each other, with white lips, ‘When will this damnable work end? Whose wife is safe as long as these bloodthirsty hellhounds can commit such crimes in the heart of the city?’ ”

At three in the morning, still more residents were pouring into downtown—shouting, panting, stumbling in the wagon ruts. Horses became spooked and tried to bolt. Policemen blew their whistles and shouted at the crowd to stay calm. Yet downtown remained in a lather of fury and terror. Men stood guard on street corners, holding lanterns or makeshift torches and carrying weapons of all kinds—rifles, hatchets, pipes, sheath knives. “Had a man with a speck of blood on his clothes appeared, he would have been rent in pieces,” a Houston Daily Post reporter would later write.

To increase the amount of light, merchants came to their dark stores to turn on their incandescent lamps. Several women, tears streaming down their faces, huddled in carriages under the “outdoor lamp” that Charles Millett, the owner of Millett’s Opera House, had placed by his front doors so that potential patrons walking by at night could read his marquee about upcoming shows.

Finally, the sun rose. Throughout the city, church bells rang to signify the arrival of Christmas Day. But for all practical purposes, Christmas had been canceled in Austin—presents left unopened under the Christmas trees and dinners uncooked. The priest at St. David’s Episcopal Church opened his doors for a 7:30 a.m. Communion service. But only a handful of his parishioners came to take the sacraments. There was no music at the service because none of the choir members arrived to sing.

By late morning, the newsboys for the Daily Statesman were on Congress Avenue, hawking the Christmas Day edition, which had been reprinted overnight. “Blood! Blood! Blood!” screamed the new front-page headline, the ink scarcely dry on the paper. “The Demons Have Transferred Their Thirst for Blood to White People!”

People read the story, over and over, in disbelief. Even those who had already been told details of the killings gasped when they got to the part of the story describing the firewood laid across young Eula Phillips’s body—“evidently used for the most hellish and damnable of purposes,” noted the reporter.

Holding their newspapers, some citizens walked down Congress Avenue to the Hancocks’ home and then back up to the Phillipses’ to look at the yards where the women had been found. How was it possible, they asked, that neither woman had cried out when struck by an ax? And how could no one have heard the attacks taking place? Both families lived in the middle of busy neighborhoods. At the time of the attacks, there were still some Christmas Eve revelers out and about on the streets. And there wasn’t a single eyewitness to either of the killings?

At the police department, Lucy ordered Chenneville and his officers to round up black men who had been suspects in some of the previous murders and bring them to the city jail. Each man was told to remove his shoes, place his feet in a bowl of ink, and step down on a sheet of white paper to see if his footprint matched the bloodied one that had been cut from the floor outside Eula’s room. But there were no matches.

Later that morning, a desperate Mayor Robertson convened a public meeting at the temporary state capitol. More than seven hundred men packed into the House of Representatives’ chamber. They jostled against one another, all of them talking at once, their voices thick with anger—“an infuriated multitude, white with heat,” wrote the Houston Daily Post.

Frank Maddox, a general land agent, called for the city to hire a hundred secret agents, known only to the city marshal, who would hunt down “the assassins.” Nathan Shelley, a former Confederate general, rose and demanded that “a cordon of sentinels” be placed around the city’s limits that very afternoon. He suggested that once they were in position, these sentinels should start moving forward, step by step, questioning every man in their path and asking about his whereabouts in the last hours of Christmas Eve. If a man’s answers were “inadequate,” Shelley said, the sentinels would be allowed to take “appropriate measures.”

A number of men called on Mayor Robertson and the city’s aldermen to agree to a temporary suspension of normal criminal statutes and allow for “lynch law,” which would grant anyone the power to make a citizen’s arrest of a murder suspect, do whatever he wanted to do to that suspect, and not suffer any legal consequences for his actions. But Alexander Terrell, a longtime Austin lawyer, begged the men in the hall to let Marshal Lucy handle the investigation. “A vigilance committee means blood, and is likely to victimize the innocent,” he said. “When it rules, reason is dethroned and ceases to act. It would be fruitless of results and bring about calamities you would deplore.”

Terrell pointed to the men supporting a vigilance committee and said, “You men can’t find the killers, marching around the city!” The men roared back that they damn well could. One of them yelled that the killers, when apprehended, should be taken to the expansive grounds of the new capitol building, which was under construction, so that their hangings could be witnessed by all of Austin’s citizens.

It was finally agreed by a voice vote that a Citizens Committee of Safety be formed; each of the city’s ten wards would supply four men. The committee would raise money for a reward fund and assist in the police department’s investigations. Robertson and the city aldermen then met at city hall, where they passed an ordinance authorizing Marshal Lucy to hire thirty additional police officers, giving him fifty officers in all. They also passed an ordinance requiring all saloons, where the aldermen believed the murderer or murderers were no doubt meeting to plan their crimes, close at midnight and not reopen until five a.m.

By now it was five o’clock in the afternoon. At the police department, Lucy began hiring his new officers, pinning badges on their street clothes and sending them out to work with Chenneville and the other officers. He ordered his men to “halt” all strangers they saw, demand their name and address, and have them explain why they were out and about. If any stranger could not give “a good accounting of himself,” he was to be taken to the jail, given a more “extensive interrogation,” and kept there “until morning, at least.”

Deputies from the sheriff’s department and the U.S. Marshals Office also showed up to help patrol the neighborhoods. Members of the newly formed Citizens Committee of Safety walked around their wards. Despite the overwhelming law enforcement presence, however, few residents slept. Inside many of the homes, husbands pushed furniture against doors and nailed wooden planks or blankets across windows. Fully dressed, they walked their floors, cradling rifles, stopping every few moments to listen with straining ears for the sound of an invader. Those who owned telephones would pick them up to hear if any new attacks were being reported on the party line.

But there were no attacks and no attempted break-ins. There were no sightings of a “stranger.” Periodically, a police officer would bring his horse to a complete stop because he thought he had heard the shuffling of footsteps or the snapping of a branch. He would sit there for a few seconds, staring at the shadows. But no one emerged. The only sound came from the officer’s own horse blowing steam into the air and twitching his tail.

Twenty-four hours had passed since the Christmas Eve attacks, and still no one had a clue as to what was happening. Austin’s terrified residents could not help but wonder: was the “gang” of black killers now coming after the city’s white women? Or was there a gang at all? Was it possible, as one of the newspaper reporters had written earlier, that a brilliant but diabolical “Midnight Assassin” was on the loose? And was it possible that he was about to strike again?

Excerpted from The Midnight Assassin: Panic, Scandal, and the Hunt for America’s First Serial Killer, by Skip Hollandsworth. Published by Henry Holt and Company LLC. Copyright © 2016 by Walter Ned Hollandsworth. All rights reserved.