This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

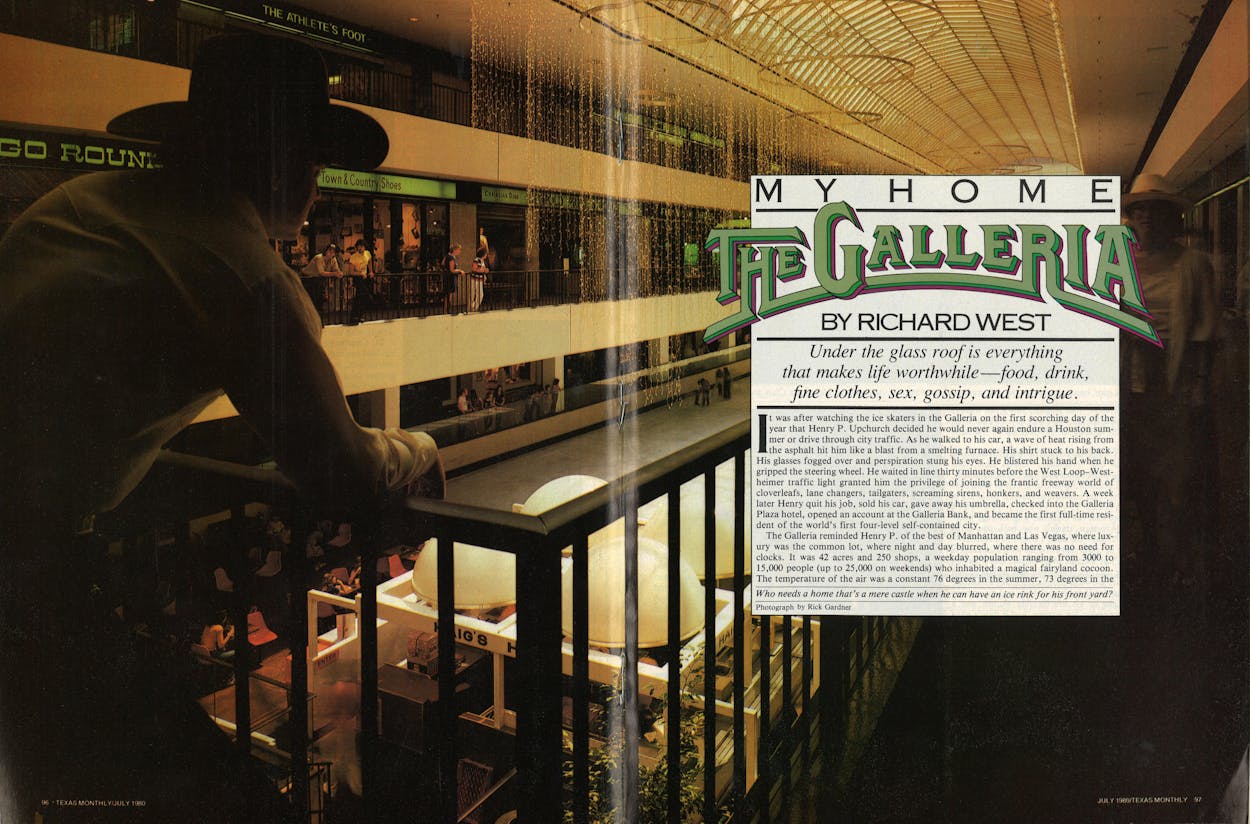

It was after watching the ice skaters in the Galleria on the first scorching day of the year that Henry P. Upchurch decided he would never again endure a Houston summer or drive through city traffic. As he walked to his car, a wave of heat rising from the asphalt hit him like a blast from a smelting furnace. His shirt stuck to his back. His glasses fogged over and perspiration stung his eyes. He blistered his hand when he gripped the steering wheel. He waited in line thirty minutes before the West Loop–Westheimer traffic light granted him the privilege of joining the frantic freeway world of cloverleafs, lane changers, tailgaters, screaming sirens, honkers, and weavers. A week later Henry quit his job, sold his car, gave away his umbrella, checked into the Galleria Plaza hotel, opened an account at the Galleria Bank, and became the first full-time resident of the world’s first four-level self-contained city.

The Galleria reminded Henry P. of the best of Manhattan and Las Vegas, where luxury was the common lot, where night and day blurred, where there was no need for clocks. It was 42 acres and 250 shops, a weekday population ranging from 3000 to 15,000 people (up to 25,000 on weekends) who inhabited a magical fairyland cocoon. The temperature of the air was a constant 76 degrees in the summer, 73 degrees in the winter. April was no different from August, July green was the same as November brown. The only sure way to tell winter from summer was to note the change in the clothing of the daily swarm.

It wasn’t long before Henry was congratulating himself on his brilliant decision. He had everything under glass, air-conditioned, and at his fingertips: food, bars, entertainment, shops, books, romance, glamour, sports, and, best of all, a constant change of characters that constituted the best street life in Texas.

Henry P. soon learned that the Galleria, with its huge international clientele and foreign shops, was both the most cosmopolitan space in Texas—the state’s own Fifth Avenue— and a small town where he could make friends with shopkeepers and regular customers just like on Main Street, USA. Living here, Henry no longer felt the loneliness and isolation that seemed endemic in a fast-growing, mobile place like Houston.

An unexpected bonus was that his social life had never been better. For the first time in his life meeting women was a pleasure instead of an occasion for anxiety, and it didn’t have the sleazy overtones of meetings in singles bars. Because of the nature of the place—the comfort, the stores pressed close together with open doors—people shed their inhibitions as they satisfied their lust for buying in this landscape of expectation and luxury. He met and dated women from all over the world—shoppers, tourists, conventioneers, and old friends from college, as well as a few who were more in keeping with the commercial aspects of the Galleria.

He had met Monica in the bar hidden away behind the darkened windows of the Pacesetter Restaurant on Level One, appropriately deemed the “leisure level” by the mall management. Henry often stopped by during the cocktail hour to eat the free canapés and watch the travel slides. He would sip a beer and stay until the pianist’s second rendition of “Feelings” ran him out. Monica was tall and pretty, and dressed, shall we say, rather boldly—in gold lamé from head to toe. She wore her natural blonde hair in the mall’s newest hairstyle craze, a Suzanne Somers ponytail that sprouted from one side of her head. She sat down, asked him for a light, glanced at his Stetson, and asked if he owned a ranch. He replied that he wasn’t a cowboy, just liked the clothes. At that point her purse beeped.

“You’re nice,” Monica said. “Why don’t you wait here and I’ll be back in an hour?”

When she returned, Henry told her about his new life in the Galleria. That cemented their friendship. Why, they were practically neighbors! Monica, after all, was as much a part of the Galleria as a chic store manager or the executives jogging on the rooftop track, and Henry warmed to her with the same curiosity he had about the other inhabitants of his new world. She was 23, a native Houstonian, married young to a bad man, and supporting a six-year-old son. “My husband beat me like a redheaded stepchild,” she told Henry in a flat, emotionless voice. She worked the two Galleria hotels almost exclusively and had never been arrested. The purse beep alerted her to call an answering service to learn the client’s hotel and room number. Monica prided herself on being a member of her profession’s upper class—she charged $100 an hour and had made $32,000 last year—and not part of the rabble that trolled in cars past the entrances of the two hotels trying to catch lonely businessmen.

The night after he met Monica, Henry took her on his typical Galleria date expedition (interrupted by three beeps during their six hours). They began back at the M. Pacesetter bar and sipped Pimms Cups while the Acropolis and the Swiss Alps flashed on the wall. She was delighted with his peculiar life and demanded the latest in Galleria gossip, which Henry P. could easily supply, since he was a rather skillful snoop.

“What juicy tidbits have you learned today, Henry-P-Upchurch?” Monica asked. She thought his name pretentious and never failed to pronounce the whole thing—Henry-P-Upchurch—as if it were one word.

“People stand outside Suzy Creamcheese and peer in as if they might come upon acts of unspeakable evil inside. Once they go in, however, they love it.”

“Well, where to begin, Miss Monica,” Henry said. “The Pacesetter Restaurant right in front of us has been plagued with grease fires lately. They owe King Gerald Hines over $11,000 on their HVAC bill—that’s Heating, Ventilation, Air Conditioning in Galleria talk—and want to extend their lease, but Hines won’t sign anything until the HVAC is paid, you can bet on that. El Fenix across the way has been warned about their overloaded electrical panel—probably from all their electric can openers.

“Now let’s go up to the Roof for the upper-crust free eats,” said Henry P. as he heard the familiar opening chords of “Feelings.”

“Who is Gerald Hines?” Monica asked.

The Roof was the crown of the Houston Oaks Hotel, a restaurant-bar where Galleria office workers and tourists gathered for hot appetizers and a little dusk music by the Family Tree, a band that played safe, anemic rock, occasional country, and endless repeats of Donna Summer’s hit “On the Radio.” There was a wraparound view of the surrounding territory so patrons could monitor the freeways and decide if the traffic density justified another cocktail.

“Gerald Hines built and owns the Galleria, all of it,” explained Henry. “He is our Landlord and Master. He owns a lot of other buildings you can see from here, including One and Two Post Oak Central, those beautiful silver glass and dark aluminum striped buildings over there. He’s a genius. Wasn’t that your purse sounding off?”

It was, and Monica promised to meet him for dinner at the Shanghai East Restaurant in an hour.

In the cool, antiseptic atmosphere of the Galleria, only two places could be counted on for good, strong odors. Outside the Best of India shop, Raj Bhagwan’s incense sweetened the air, and in the Shanghai East corner on Level Three, the dense, pungent smell of Szechuan cooking almost made the eyes water. This had caused a tiff between the restaurant and the University Club, a private exercise facility located above the restaurant on the Galleria’s fourth level. What infuriated University Clubbers was that the Szechuan smell permeated their lounge and dining room. They had a point. The heady mixture of Aramis cologne and mooshi pork was not the best.

Henry P. and Monica judged window displays on the way to nightcaps at Annabelle’s, the disco atop the Galleria Plaza. (The fancy shoe boutique Charles Jourdan won.) Monica ordered one of the club’s toy drinks, something called a Disco Inferno with 151-proof rum, but duty beeped and she left for the Oaks after thanking Henry for the evening.

He began to plan his itinerary for the next day. It would be a full-sweep operation, from his hotel on the southwest corner to the foundation stone of the whole Galleria empire, Neiman-Marcus, on the eastern edge. Neiman’s remained the imperial palace of Hines’s kingdom, and Henry had important rumors to check out there, including the romantic story of Lisa and Larry, the Galleria’s most glamorous couple. Larry Schatzman, vice president and store manager of Neiman’s, and Lisa Ikard, the beautiful former public relations director, had fallen in love in a spectacular intrastore romance and were now living together in Larry’s townhouse two blocks away on Westheimer. Henry P. had to know more.

“Because of the nature of the place, people shed their inhibitions as they satisfy their lust for buying in this landscape of expectation and luxury.”

From his back table at Annabelle’s he looked down at the high-tech grid design of the newer Galleria 2 skylight and office towers, then over to the older Galleria 1 complex on the east. Here was the Gerald Hines kingdom that made life in Houston livable for him.

During the years when Gerald Hines was selling air conditioners for Texas Engineering and cars—unsuccessfully—at a Lincoln–Mercury dealership, he saw the future. Downtown Houston was dying. Commercial real estate development lay out on the bald prairie west of downtown, along freeways looping around the heart of the city. Hines correctly predicted Houston’s fantastic growth and realized that the sprawling city had to be cut down to several “nodes,” human gathering points along the road, cosmopolitan islands of business and pleasure.

By 1966 Hines had built thirteen office buildings in the Richmond area and had decided on his primary node site, the Post Oak area on Westheimer near the West Loop, five miles from downtown—1500 acres that would become one of the hottest retail spots in the country. Sakowitz had already built its store there in 1959. Joske’s followed in 1963, one year after the linkup of the West Loop with the Southwest Freeway. In spring 1967 Hines announced his $40 million Galleria project after persuading Neiman-Marcus to become his first tenant in the Galleria rather than building their new store east of the West Loop. Hines took the name and idea from the famous Victor Emmanuel II Galleria in Milan, opened in 1860 as a monument to Italy’s unification. The architect, Giuseppe Mengoni, had devised two covered streets with shops, offices, and cafes. Mark Twain, Henry P. Upchurch’s hero, had visited the Milan Galleria and later wrote in A Tramp Abroad that he could live there forever.

Hines brought together the three essential elements in any large commercial development—the developer, the financier, and the tenant—and he personally followed every aspect of the Galleria’s birth. Success depended on persuading prestigious stores to settle in the Galleria. The second tenant to announce was Tiffany’s, followed by the four-hundred-room Houston Oaks, the second Western International hotel to be located outside a downtown area. The Oaks deal persuaded Isabell Gerhart to move from her catbird location on the choicest corner in River Oaks—River Oaks Boulevard and Westheimer—to the Galleria. The respected Houston women’s clothing store contracted for the largest amount of retail space up to that time—25,000 square feet—and opened a store with an entrance in the lobby of the Oaks. Then followed General Cinema’s two theaters in October 1968, the well-known New York leather company Mark Cross, in November, and numerous other smaller stores.

Neiman’s opened its $10 million store fourteen months before the official Galleria opening. Outside, Hideo Sasaki’s $240,000 landscaped sunken garden surrounded the bridge entrance. He had built the oasis around three old live oak trees that had stood by the little red Grady Elementary schoolhouse on the Galleria site in the late forties and early fifties. Inside, escalators penetrated the central light well that ran from the mall floor to the skylight. Piercing two floors near this well was Stanley Landsman’s 26-foot glass-and-light sculpture, Far Side of the Moon.

The designer of Neiman’s and the rest of the Galleria, Gyo Obata of the St. Louis firm Helmuth, Obata, & Kassenbaum, called his Neiman’s plan “the treasure chest.” For the Galleria itself, Obata designed a 150-yard-long, 40-foot-wide skylight, cantilevered its shoulders to make the central mall freestanding, and joined the three levels with stairs and escalators. But the real stroke of genius was putting a 180-foot-long, 85-foot-wide ice rink on the first level as the vortex around which all activity swirled. All the shops opened onto it. Crowds came to watch, to meet friends, to join the throngs underneath the dangling tendrils of Italian Christmas tree lights hanging from concentric rings above the rink. The continuity of the Galleria’s interior was accomplished by using dark tobacco-brown carpeting on two levels and a brown flash-marked brick on Level One; subdued colors on the walls as a foil for the brightly lit storefronts; and a sign channel that created the effect of a continuous band of mirror along all the storefronts.

Into Obata’s design could be plugged additional buildings when they were needed, such as the Post Oak Tower office building (1970), Transco Tower (1972), and Galleria 2 (1977). When the Galleria opened in November 1970 with sixty stores, it was 65 per cent leased. One hundred per cent leasing didn’t happen until a furnishings store named Columbus, an upper-class Pier One, joined the complex in 1973.

In June 1972, less than two years after opening the Galleria, Hinds announced a $61 million, 1.5-million-square-foot expansion at the west end of his original project—Galleria 2. It would be anchored by Lord & Taylor’s second Texas store and another Western International hotel, the five-hundred-room, $17.5 million, 24-story Galleria Plaza. Galleria 2 had a different character. It was more exclusive, with international boutiques such as Ted Lapidus, Carrano, Caruggi, and the Italian linen shop Frette. Galleria 2 had its share of mass-appeal shops— Casual Corner, J. Harris, and the fast food eateries near Cinemas III and IV—but the ambience told you it was going to cost more once you stepped off the Galleria 1 carpet onto the Galleria 2 tiles.

There was, of course, already a Galleria 3 planned for the nine acres left in Hines’s original chunk of land. Another well-known department store, probably I. Magnin, would join Neiman’s, Lord & Taylor, and Marshall Field along Westheimer, and another hotel would anchor the south side. The 54-year-old Hines acted as if he had just begun to build. He planned to break ground on over $200 million worth of office buildings in 1980, and next year he would export his Galleria concept to Dallas. It is a rare man who can truthfully state that he has changed the way we live. Hines could. He had changed Henry’s life more than anyone else’s, perhaps, but his way was the way of the future. Everyone visited the Galleria eventually.

Just before dawn on his busy day, Henry P. Upchurch sat beneath the skylight in Galleria 2 near the glass elevators and watched the darkness wear off and the windows lighten. For the moment he was alone. The sweepers and polishers had finished their work. Late-night strollers from the two hotels had gone to bed. The Muzak and the crackling static from the security force’s radios had ceased. Finally a sense of emptiness permeated the structure, and the only sound Henry heard was the cold air surging through the arteries of the Galleria’s vascular system.

He walked toward Galleria 1 and watched the slowly rotating clothes bag and spinning windmill in the window of Houston Trunk Factory, both powered by electric wind. The only weather he missed was breeze. Sometimes he would stand in mall kiosk shops like Forty Love and It’s My Bag to feel the ruffled air from their ceiling fans. As he neared Galleria l’s arched skylight, Henry noticed a faint sunpath on the ice rink below, the sign of another hot day. Businessmen–runners were already jogging on the roof of the mall. Near the ice rink’s ticket office a few movie technicians wearing heavy coats were drinking coffee and comparing KIKK belt buckles and other local souvenirs. After a while they began stretching cable and setting up cameras to film Telly Savalas in a scene for Hellinger’s Law, a two-hour CBS-TV movie.

Some of the rink’s better child skaters had been chosen for the scene, and they were jumping and spinning and moving backward on the ice as if drawn by a huge, invisible magnet. The inevitable group of Houston extras that always gathered for local filming—character actors, models, well-kept retired swells —registered with the casting director. The only requirements for being in Law seemed to be to show up early and be ambulatory. The locals would portray shoppers strolling back and forth across the bridge above the ice rink while Telly and a younger man chatted and watched the skaters.

“Could someone get Tell some coffee? Right away, please.’’ Henry recognized the speaker as Paul Picerni, Robert Stack’s right-hand man in The Untouchables. Now he was Tell’s business associate. Telly appeared—big, beefy, bald—dressed in brown slacks, gray coat, white shirt, brown shoes, and gold chains. He graciously signed autographs until the shot was ready. Tell had mastered the art of saying the nicest things with an ugly sneer, and his fans loved it. After three hours of preparation, the filming lasted five minutes. “Tell, we have to go. Say good-bye,” pleaded Picerni. “Love ya, baby,” sneered Telly sweetly, and the two men hurried off, followed by their minions. Henry thought it was rather touching, for here were two men representing different generations of television cop shows, father Untouchables and son Kojak, enjoying show biz and fame together.

By now the shops were open and the pace of the mall had quickened, with people rising and sinking on escalators, wandering in and out of open doors, and stopping to watch the movie roadies pack up equipment. Galleria rules stated that stores were to follow the operating hours of Neiman’s in 1 and Lord & Taylor in 2, ten to nine on weekdays, ten to six on Saturday, optional on Sunday (for those stores not required to close by the blue law). Many places, however, varied their business hours slightly and suffered no consequences except a gently scolding letter from the mall managers. The ice rink was open every day of the year. Many shops remained open on Sunday—record stores and bookstores, most of the restaurants, the movie theaters, and mavericks like the Berry Tree card and gift shop.

Walking with the crowds back to Galleria 2, Henry headed for Au Chocolat, where he always had breakfast. To begin the day with one of Herb Pasternak’s pure imported Swiss Teuscher chocolates was to die. Even Stanley Marcus preferred the Teuschers to his store’s own Godiva and Neuhaus candies, and when he was in town, he sent over a chocolate runner for his favorite, the champagne truffle. Henry, like Stanley, preferred this top-of-the-line item, made with fresh whipped cream and butter, so fragile it had only a three-week shelf life, but today he would dare to be different. Perhaps one of the nougat truffles with fresh nuts on bottom and top and whipped chocolate and butter in the center, or one of the Florentines—tiny slices of green Italian melon and red cherries on a bed of chocolate—that reminded Henry P. of a pizza. Like Henry, Herb Pasternak didn’t like the summer. Candy sales dropped because bathing suit months were not chocolate months. Also, some of his most delicate offerings, such as the marzipan dates, melted on the tray despite the air conditioning.

Knowing he would need plenty of energy for his busy day, Henry chose a walnut truffle and a Florentine to nibble on while he walked toward Marshall Field, the new three-level store that had opened last November. It managed to look more inviting than the two other big Galleria 2 department stores. Frost Bros., across from Au Chocolat, was the Darth Vader of the group—dark, mysterious, almost menacing, except on the brighter second level. Mall gossip had it that Gerry Hines had signed Frost to attract the popular Gucci line, which was available at a boutique inside the store. The designers of Lord & Taylor provided it with a cathedrallike entrance, perhaps in keeping with the name, but they should have built three levels rather than two. The store felt claustrophobic, cluttered, and disorganized. Lately, though, operations and sales had improved, thanks to Mike Hofmann, the new manager.

Marshall Field had been designed by Philip Johnson, who was responsible for many of Hines’s buildings. Henry was glad Mr. Field had vetoed the Claes Oldenburg scatter-effect artwork proposed for the Marshall Field facade, for he liked the building’s pure lines and confident curves. The Great Wall, mall people called it. In this first branch outside Chicago, Field’s wanted to fill the gap between a basic department store like Foley’s and a fine specialty store like Neiman-Marcus. Marshall Field, Lord & Taylor, and Frost Bros., all in Galleria 2, fought for this middle market, and that was why service and interior layout were so important. Field’s had a great gourmet food department, a not-too-bad in-house restaurant called the Restaurant, a popular menswear section (which generated 15 per cent of the volume in 7 per cent of the space), and disappointing sportswear and lingerie sections.

The Frango mint had been a Marshall Field specialty since 1921. It once had been called “Fran-co,” but certain political developments in Spain during the thirties had prompted a name change. To commemorate the opening of Marshall Field in Texas, Frango wizards had invented the orange Frango. Each night a Galleria Plaza maid placed a cardboard packet of two Frangos at Henry’s bedside. They were better than Godivas, but not as good as Swiss Teuschers.

Henry walked through the store’s huge cosmetics department—what seemed like an acre of makeup—marveling at the iridescent faces of the salespeople. These servants of beauty with their expertly applied powders, liners, lip paints, and blushes were busy lining and painting and powdering customers, giving advice, and squirting on scents. Henry’s nocturnal friend, Monica, knew perfumes. She wore the best, Bal a Versailles ($75 a half-ounce, $400 for four ounces), which had a sexy touch of musk but mostly smelled like flowers. An expensive attar, yes, but its effect was priceless.

Thinking of high fashion reminded Henry of the window-dressing faux pas that had occurred in the Galleria not long ago. The same $1500 Oscar de la Renta dress had accidentally been displayed in the windows of Frost Bros., Isabell Gerhart, and Neiman-Marcus on the same day. Oh, did that cause the clucking and rearranging. Everyone tried so hard to be different, but only one dress shop in the mall succeeded.

Henry had heard Suzy Creamcheese described as an art gallery, a harem, a house of ill fame, and a shrine to decadence. People stood outside and peered in, a little hesitant to enter, as if they might come upon acts of unspeakable evil. Once they did go in, however, they loved it. The shop was so popular that on Saturdays—the looking-rather-than-buying day—the manager, Cherie Bowen, had to put a theater stanchion across the entrance to control the customer flow. Suzy, just outside Marshall Field’s second-level entrance, sold wonderful, outrageous clothes—antique silks, silk chiffons, hand-painted tux shirts ($90), hand-painted jogging suits with a flower on the left leg and a flower, lips, and an eye on the front of the jersey ($125), Victorian lace wedding dresses ($2500), glitter fabrics, spandex, pure silk, hand- embroidered costumes and party things. Suzy’s average price was $300. The store had done very well during Houston’s rodeo madness last February with sequined chaps, Buffalo Bill fringed leather shirts, and sequined-yoke blouses.

But even the wild clothes in Suzy Creamcheese paled in comparison to its decor. Billowing silks ($135 a yard), hand-dyed and hand-embroidered, hung from the ceiling like parachutes. Moroccan arches with bas-relief scenes on one wall, ombré satins shading from light to dark on the other wall, handmade glass beads, Persian carpets, tiger-striped wallpaper from the thirties, brass lamps from Norbert’s in Houston, antique doors and a couch from Austin, and a mirror ball that hung from the center of the ceiling, throwing light around the room, completed the ambience. The store reflected Ms. Creamcheese’s love of expensive gypsy fashion and the work of Erte, the famous Russian fashion artist and designer who created Harper’s Bazaar covers from 1915 to the thirties. A collection of his designs has been purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

The staff was still atwitter over the visit of Maria Felix, the Marlene Dietrich of Mexico, who had swept in wearing her 62-carat diamond and a belt made of $20 gold pieces. She had bought a handmade, hand-painted, hand-beaded coat, necklace, and belt adorned with peacock feathers ($2800). Henry chatted with Cherie on the Austin couch beneath the New York tiger wallpaper and met Suzy Creamcheese’s daughter, Marci, who was learning the ropes by working in the Houston store.

Suzy Creamcheese was famous. She had started at the Whisky-A-Go-Go in Los Angeles as a waitress and go-go dancer. She had begun designing clothes for her rock ’n’ roll friends (she took her name from a Frank Zappa song), then made it big with her store in Las Vegas. Now one of her favorite customers was Miss Lillian, mother of Jimmy Carter, who wore a size eight. Suzy did Miss Lillian’s clothes for the Merv Griffin show.

The Creamcheese crowds forced Henry P. back into the mall and he walked toward the elevator area, where soon the Houston Symphony would play a noon concert and later Harper’s Bazaar would stage a style show. This was also the place where, a year ago this spring, a girl in her early twenties had jumped to her death from the fourth level. Walking north toward Lord & Taylor, he passed Jag, the fancy jeans store that offered a pair of jeans for $500 with “Jag” written on the back in rubies. Jag, operating from Los Angeles, had not done well. Now it had been bought and would be run from Houston. You could tell from the storefront that times had been bad: the l ’s were missing from “Hills” as in Beverly, the t and n from “Houston,” and the k from “York” as in New.

The spectacular failure in Galleria 2 had been Diversions, a hangout for teenagers that featured sixteen bowling lanes, a small disco, a bar, a sandwich area, and electronic games. The predictable things happened: a little dope pushing, cut-rate prostitutes, a shabbier clientele than the Galleria bosses preferred. The mall managers were lucky that Diversions had begun its stay undercapitalized and could be legally evicted. For many months Diversions’ owners had failed to pay their minimum monthly rent ($11,111.72), merchants’ association fee ($402.17), HVAC ($2016.25), common area maintenance charge ($4203.06), and the repair bills for plumbing, broken tiles, rest room repairs, and on and on. When it vacated earlier in the year, Diversions had owed more than $340,000.

Providing entertainment for teenagers was still a problem. Kids from far-flung suburbs came to socialize in the Galleria and often brought the problems of suburban boredom with them—vandalism, car theft, drug commerce, petty larceny, shoplifting. Top Ticket, a concert-ticket outlet on Level Three near Diversions, had also closed. Nearby tenants and the management held a good-riddance attitude about both places.

Walking on past Jag, Henry stopped to check out the astonishing three-inch-long, clawlike blackberry fingernails on the hands of Roxie Everett, who managed Jellybeans & Fiddlestix. They matched her blackberry-orchid lipstick. Roxie’s shop sold designer clothes for kids—Ralph Lauren polo shirts, Calvin Klein and Sasson jeans, terry-cloth robes by Dior—and items like a beautiful French handmade lace christening gown (a steal at $900). Growing fingernails was Roxie’s hobby, breaking them the bane of her existence. She had a handsome store—eleven-foot-high mirrored walls, mirrored platforms under the window mannequins—but she was the show.

Across the way, Mahmud Yusuf, the friendly Pakistani who was manager and part owner of Copperfield, waved to Henry. Mahmud had been an actor in New York before deciding to sell Giorgio Armani suits to men who wanted to be American gigolos.

Over coffee Mahmud told Henry about the senator from Mexico who had come in the day before with his six sons and bodyguard and bought fifteen Armani suits (average cost: $500), several $50 shirts and $30 ties, and a few $95 Boulevard shirts with the hidden front zipper. “If it weren’t for the international customers, I would not make it,” Mahmud told Henry in his calm, earnest manner. “They represent eighty per cent of my business. Mexicans want to be gigolos, too.”

Especially in the more exclusive Galleria 2, the growing Mexican and South American trade was crucial. The discovery of oil had created a moderately wealthy class along with the very rich. They came to Houston for three reasons—to buy clothes, to shop for gifts, and to use the city’s fine medical facilities. They arrived in great numbers three times a year— during Easter holidays, before school in September, and at Christmas.

Almost every store owner had a story about small Mexican children buying cheap items with $100 bills. Not long ago Henry had watched a Mexican couple enter the Galleria Plaza with ten Louis Vuitton suitcases. His bellboy friend, Phil, told him that seven of the bags were empty but would be full on the trip home. He explained how some foreign customers avoided paying duty charges on new purchases by sending the newly bought clothes to the hotel cleaners or by washing the just-bought socks, lingerie, towels, or handkerchiefs. Once-cleaned or once-worn booty was not subject to import payments.

Across the mall from Copperfield, Henry P. spotted one of his favorite store managers, a good ol’ boy from Roby, Texas—that’s between Rotan and Sweetwater—named Jim Beene, who managed the Charles Jourdan shoe boutique. Beene had learned the shoe game at Neiman-Marcus before opening his own shop two years ago. So had his boss, Joe Moore, the president of Jourdan, who had once been Neiman’s shoe salon buyer. Beene resembled a craggy George Peppard with his wide, friendly West Texas face, and he knew the size of women’s feet in all parts of the country.

“Big feet up north. Now those women come equipped with something to walk on,” Jim stated with authority. “They got small feet in the Southeast—two and a half, three B’s. Got plenty of small feet here in Texas, although I’d say the average Texas woman’s foot is seven B. More small sizes are sold at this Jourdan store more than at any other, though. Mexicans have a fairly small foot. They make up about 25 per cent of our business. Wish it were more. When times get tough the wealthy Houstonian cuts back on the throttle a bit. Not our friends from the south.”

Beene also told Henry about his most frequently shoplifted item, his expensive silk scarves ($140, $275, $400), and about the thieves who broke into one of his trucks and then tried to exchange the stolen shoes for their sizes. “Now that was real stupid,” he laughed.

Henry was amazed to discover that no central alarm system for the stores existed in the Galleria. Shop owners were responsible for their own systems. This way, SETEC, Hines’s security company, was liable only for the public domain. Shoplifters most often hit the smaller stores, because they usually didn’t have cameras or plainclothes security cops and seldom pressed charges. They only wanted the goods returned. The larger stores were tough on shoplifters. Still, Marshall Field had already been broken into twice, once through the front door on Westheimer. Security officers had responded quickly, but the robbers escaped both times.

It was high noon and a crowd of shoppers and office workers had gathered to listen to the Houston Symphony, which had set up near the glass elevator well. The young associate conductor, C. William Harwood stepped up to the microphone in front of his musicians and announced a selection from Handel’s Water Music. Secretaries listened from their office balconies overhead. Children squatted down in front and followed the conductor’s jerky movements with their eyes. Shopkeepers stood in their doors and toe-tapped. Brown-baggers sat beneath the mall’s trees and chewed pensively in rhythm with the music. After 45 minutes the musicians closed the program with the rousing overture from Carmen, which sent the audience swaggering away in a festive mood.

North of the elevators, a runway and stage had been erected for the Harper’s Bazaar style show, titled “Images of Success.” The clothes came from Marshall Field, Elico, and St. Germain—none from Neiman-Marcus. Neiman’s stood aloof from mall activities even to the extent of not letting its models or clothes be photographed with merchandise or models from other stores. Neiman’s people thought the rule made them distinctive. Others thought it simply snotty. The show’s coordinators and models were working out of St. Germain. Henry had seen the store’s delinquency report, which showed a debt of $16,316.14 owed to Hines in March. Henry had also heard that St. Germain held counterclaims against Hines and wondered if landlord and tenant had settled their differences. He liked the store and hoped the show would generate many sales of the orange knits, white linen suits, and white jackets and pants that were about to be paraded before the customers.

He stepped inside and watched the models. Henry P. had discovered that modeling was very hard work. These tubular, serpentine, concave figures had to be almost asexual. They had to walk a fine line between drawing attention to themselves—hardly at all—and their clothes—a lot. Models had to create a world of glamour through their looks, vitality, character, and intelligence so that customers would feel they also could be glamorous. They were delicate creatures with fragile egos and usually had unhappy personal histories. Men married models for their beauty and arm-piece appeal, then kept them home and tried to change what they had married them for in the first place.

In St. Germain, style show coordinators placed tape on the bottoms of the models’ shoes to lessen the chance of slipping and made sure they had not used perfume on their necks, wrists, or other body areas that the clothes touched. Most knew better and wore no scent or hand jewelry, except wedding rings, that would divert attention from the dress. Diamond rings were turned palmward. Henry watched Kay Emberg, a woman about 45, one of the top models in the Southwest, as she prepared to go on. The face of her daughter, Kelly Emberg, a top New York model, usually graced at least one fashion magazine each month. Kay assumed the expression of an actress ready to walk onstage and, with great confidence and angularity, walked onto the ramp as the commentator began describing her outfit.

Living in the Galleria had forced Henry to pay close attention to women’s clothes for the first time. About 40 per cent of the stores in the complex sold clothes, and the mall was a panorama of well-dressed women. Henry had long thought of high fashion and all its accoutrements as representing society in its shallower aspects, but actually the changes in fashion through the years reflected social change. If the Galleria were an archeological site, it would reflect only a frozen moment in history. It was fiercely current, from clothing styles to the New Wave music blasting out of the record stores (the Galleria’s radios) to the $3400 six-foot Advent television screens in Video Concepts.

Later Henry joined three teenagers for a shopping expedition. Laura, Allison, and Sandra, all eighth-graders at Rogers Junior High School, represented one of the most dramatic changes in women’s fashion in the last twenty years. Before the mid-sixties, thirteen- to nineteen-year-olds were only a tiny fraction of the market. Now this age group bought about half of all dresses, skirts, and coats. Like these three girls, the current teenage look was urban and middle-class in origin. What had begun in the late fifties with California casual wear and blue jeans now encompassed all styles and types of clothing, a $100 million market.

At Rogers Junior High there were three broad groups of students, according to Laura, Allison, and Sandra. The “jells” or “jellies” were the dopers, nonstudiers, and drop-out-and-get-a-job kids. The “kickers” loved rodeo, country-and-western music, and Western wear and dreamed of pickup trucks. The “jets” were the athletes, student leaders, cheerleaders, and honor-roll students who dressed preppie in LaCoste Izods, Lauren polos, madras, and khaki to achieve the return-to-frat-rat look. All three of these girls were firmly in the jet camp. They had earned their shopping money by working, usually baby-sitting, and were dressed correctly in jet attire—jeans by the Gap, Levi’s, or Sasson baggies, with tennis-style shirts. They were spirited and demanding, handsome and bright, well scrubbed and eager to buy.

Henry followed them into Lerner’s, which was on Level Three of Galleria 2, above Jellybeans & Fiddlestix. The girls began appraising Bermuda shorts and tropical shirt-and-shorts sets. Laura had the most money—$32, $20 of it designated for summer camp clothes. Allison had $12 and Sandra $10. “Everything I like you don’t like,” exclaimed one of the three from behind a clothes rack. “My dad says I look better in one-piece bathing suits.”

“You do, Allison,” Sandra said. “Two-pieces are too old for you.”

The girls picked out some brown pinstriped shorts and disappeared into the dressing room, identified as “Try On.” Lerner’s was trendy but economical, similar to J. Harris, Judy’s, the County Seat, and other Galleria clothing stores for teenagers.

“This looks like you, Allison,” teased Laura, holding out some mylar slacks and a matching bag.

“Oh, disgust,” shrieked her friend.

The girls bought some shorts, moved on to the County Seat, where Sandra bought hair ribbons, and then swept downstairs into the fancier Limited. This shop bordered on a boutique with its more expensive items: imitation bowling shirts with pictures of Hollywood, New York, and Key West on the back and Hawaiian shirts, which were very popular this summer. Henry had noticed that T-shirts were being abandoned by the mall population in favor of classic collar-and-sleeve shirts. Fashion was rediscovering the differences between men and women.

After a break for Big Macs and champagne truffles, the three girls pressed on. They browsed in It’s My Bag, a favorite stop, before descending on Marshall Field to try on more outfits and lay away bathing suits. The day’s only disappointment came when they discovered boarded-up windows instead of the Shop of John Simmons. “Oh, disgust,” announced the girls in unison.

As Henry sat resting in the mall after the girls had departed, he watched a tall, good-looking young man, about eighteen, with blue eyes and blond hair, who repeatedly introduced himself to girls his own age who were shopping alone and began an intense discussion with each one. He was very personable and had clearly mastered the art of nonthreatening introductions. He was also an expert flirt. Henry edged closer to hear what he had decided was a spiel.

“Hi. Have any young, determined men come up to you today trying to sell magazines for a contest? No? My name’s Kevin and this will only take a few minutes. I’m from Minneapolis. Ever been there? I’m selling these magazines to accumulate points to win a thousand dollars cash. You ever won a thousand dollars? No? But you can understand why I’m doing it, right?”

It was illegal to solicit in the mall, but SETEC patrols weren’t likely to spot Kevin among the huge afternoon crowds. Jon Schultz, head of SETEC, had told Henry that after a four-month legal research project last year, attorneys had ruled that the Galleria was not a public place. The customer was, in effect, a guest in Gerald Hines’s home and could be ordered to leave if certain “house rules” were broken. If the ousted guest returned, he or she could be arrested for criminal trespass. Since last August SETEC’s House Ejection Program had dramatically reduced complaints regarding the more blatant prostitution solicitations and other nuisances. Henry mentioned this to Kevin, but it seemed the least of his worries as he moved on to introduce himself to another young girl, who was watching the ice skaters.

Nearby, on Galleria l’s Level Three, across from the spicy Shanghai East corner, was the Boardwalk, a jewelry shop with a nice cactus bed bordering its window. This store had a problem. Section 3 of the almost inch-thick tenant lease stated that tenants were to pay not only a minimum monthly rent but also a percentage of the store’s gross retail sales each quarter. While checking the Boardwalk’s records for the year ending in July 1979, Archie Kramer, an auditor for Systems Technology Financial Services, discovered that the store had underreported sales by $63,436. The Boardwalk’s Rosemary Estenson claimed that “outside sales,” representing items sold or orders received away from the store, could be excluded from reported sales. Galleria 1 manager Bill Butler disagreed and told senior retail manager Bob Boyd that the Boardwalk had to pay percentage rent on the outside sales or face default proceedings.

Henry decided to pay a visit to the mall’s newest store for aristocrats, a beige-and-blue jewelry palace named Fred. There were Fred stores in France, Switzerland, Beverly Hills, and now Houston. Fred was owner Fred Samuel, who worked in the firm’s Paris headquarters at 6 rue Royale. Fred’s logo was a crown sitting on the number six. Fred had hit Houston big—helping underwrite last spring’s ballet ball, holding a black-tie pre-ball party hosted by Carolyn and Harold Farb in the new store, and bringing eight display cases of jewelry to the ball. Actress Sarah Purcell of Real People had worn Fred’s $1.5 million, 275-carat “Blue Moon” sapphire, one of several million-dollar-plus sets that Fred had trotted out to wow the Houston crowd. If Henry had any doubt that Fred was haut monde, it was dispelled when he spotted a sign reading Cuisine on the door of the employees’ coffee room.

United States Fred had been infiltrated by Texans. The man who had started American operations, now the director of Beverly Hills Fred, was Mark Lamia, an ex-Galleria Neiman’s man. On Houston Fred’s back walls were four huge color blowups of Mick Jagger’s girlfriend, model Jerry Hall from Mesquite, wearing Fred jewels. Jerry also appeared on a Fred catalog cover. And the Houston director was Cliff Bueche from San Antonio, who had mastered the art of saying things like “You have to see what Fred is trying to say” and “Everything has to make a Fred statement, it has to say ‘Fred’ ” without laughing. What Fred was saying was don’t come without big bucks. In an octagonal shaped vertical glass display case was a 25-carat diamond necklace, the stones connected with knots of angel-skin coral ($70,000), the matching watch with similar diamonds and a dial made from coral ($34,000), and matching earrings ($22,500). Back in the vault was an inch-wide $250,000 bracelet of platinum and square-cut diamonds that was so flexible you could almost tie it into a knot.

Cliff emphasized that not all Fred’s offerings were in the five-figure price range. They would be glad to do a $500 gold bracelet for a graduation gift, and as an example of Fred’s cut-rate items he pointed out a beautiful ruby ring that cost only $3000. Galleria jewelry shops ran the gamut from Fred and David Webb (the only mall shop that kept its door locked during business hours), to Tiffany’s and Cartier, on down the price list to Zale’s and Gordon’s.

Cliff talked about his competitor David Webb. “Now, I’m not knocking David Webb, but we are interested in quality. Our coral has to be the finest shade. The stones have to be top quality. Look at these cabochon stones. What? Oh, cabochon refers to a stone that’s been cut or polished to a circular or oval dome. It’s always used with translucent stones, always with star rubies and sapphires. David uses a lot of cab, but you will never find our kind of quality. Never. That is what Fred is trying to say,” ended Cliff with a flourish. Well. All Henry P. could do was agree and say good-bye as Cliff hurried over to help his staff unlock a case filled with Rolex watches. Henry P. went by to get the David Webb folks’ response, which was “They’re crazy.”

By now it was mid-afternoon. In the bright fluorescent light the thousand-limbed crowd seemed to sway along the windowless walkways in a rhythmic mass, responding to a collective, throbbing shopping beat. Henry saw no unpurposeful strollers, no aimless eyes that dreamed rather than stared. A group of kids shouted loudly in unison, “Hey teacha, leave us kids alone,” echoing the Pink Floyd refrain that drifted into the mall from Disc Records. Mixing in with the crowd, Henry could feel the heat radiating off newcomers who had entered from a world burned by sunshine, the sweat on their upper lips and foreheads drying quickly in the cool air. Thinking of the outside heat, he hurried to watch the skaters.

On the ice, among the children, whose small, brown faces were contorted with excitement, Chuck Martin whipped in and out while the kids tried in vain to catch him. Chuck had been skating for 32 years. He used to skate at the city’s old Polar Wave Ice Rink, but he had been going to the Galleria rink three hours a day, three days a week ever since its fourth day of business. At the appropriate times he dressed up as Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny, the Great Pumpkin, and Frosty the Snowman.

Skating with Chuck was his friend Nita Elliott, an actress at Marietta’s Dinner Theater and the only skater who could match his tenure at the Galleria rink. Both Martin and Elliott were concerned about the increasing crowds and the need for more guards at the rink. During the Christmas and Easter holiday periods, 400 to 500 people skated during an afternoon, 10,000 during a busy week. Occasionally a skater was sliced in a collision; once Nita had been badly cut just above her Achilles tendon and the wound had required three hundred stitches.

Nita was watching for a thin, blondish woman of about fifty who usually came to the rink in the afternoon. Recently she had been following Nita on the ice, shouting insults and cursing her. Nita knew her name and that she had a history of mental illness but didn’t know why the woman had singled her out for the abuse.

Mornings at the rink were reserved for skating lessons. On Tuesdays Henry always watched the Spirits of ’76, a drill team made up of housewives who had been skating together for eight years. Rink manager Peter Martell’s wife, Ellen, a former competitive skater turned coach, was on the ice at five-thirty each morning, with figure skating champ Josh Roberts whenever the curly-headed Houstonian was in town. Josh had started skating eight years ago as a Galleria “rink rat” and now, at eighteen, divided his time between Houston and Denver, where he trained with Charlie Tickner, who had placed third in figure skating at the 1980 Olympic Games. He practiced eight hours a day every day except Sunday and had thighs as hard as a New York banker’s heart. Now Roberts skated for the afternoon crowd, performing perfect triple Salchows—three airborne twists—and Russian splits, leaping to touch his outspread hands with his $400 skates. As he finished his last jump and slashed to a stop in mid-rink, the mall erupted in applause.

Earlier in the year the ice rink had been the cause of much hand-wringing by mall bosses. The controversy had developed when the Family, a gay group from the city’s Montrose area, rented the rink for a late-night Valentine party. Because canceling the Family’s contract for the party might bring bad publicity and possibly, lawsuits, mall managers decided to honor it. Thanks to added security from the Houston Police Department, over fifteen people were arrested in the mall for homosexual activity. In April the bosses made it firm policy: only Hines, the Galleria Center Association, and the Ice Capades can rent or reserve the rink for private parties. Thus ended what became known in the mall as the Gay Blade Affair.

Henry waved to Milt and Annie Laurie McKenzie, who like himself and Monica considered the Galleria their second home. Since their retirement four years ago Milt, who had been an electrical engineer for 34 years with Martin-Marietta Aerospace Corporation, and Annie Laurie, after 21 years as a second-grade teacher in Evergreen, Colorado, had never missed a day in the Galleria. They had driven 13,230 miles to make their 1096 visits to the mall, where they had walked (both in Adidas tennis shoes) 1650 miles. From beret to bosom flower to shoes, Annie Laurie dressed every day in aubergine (the color of eggplant). Milt favored a more conservative sport coat and slacks. Henry asked them about their previous Galleria day.

“It was one of our longest,” said Milt. “We began with breakfast at the Pacesetter and then visited Neiman’s, where Annie Laurie bought some Alexandra deMarkoff makeup and looked at dresses. Next, on to Isabell Gerhart, where she bought a dress. We looked for dress flowers and settled on some at Marshall Field, the Flower Children, and Lord & Taylor. We snacked at the Coffee Garden and stopped by Athlete’s Foot, where we had bought our tennis shoes, to get shoestrings. Then to see our broker, run a few more errands, and eat an early spaghetti supper at the Fire Engine. At the end of the evening we watched the news on the big-screen TV at Video Concepts. The car had an ‘overparked’ sticker on it when we left, but we were glad Galleria security had been watching.”

It was just like a small town, thought Henry P. Doing your business and pleasure without an auto, up and down Main Street, chatting with friendly merchants, then driving home. Like Henry P., Milt and Annie Laurie were headed to the Isabell Gerhart style show. The three of them strolled past the Coffee Garden, which would soon change its name to Zucchini’s Farm-to-Market Cafe, and Charles Beckendorf’s Texas outdoor scenes of bluebonnets, deer, oil rigs, and shrimp-boats at the Sportsman’s Gallery ($30 signed and unframed, $60 with frame) and onto the escalator that ferried shoppers down to Level Two.

The style show today would feature James Kenrob by Dalton, a line of women’s sportswear (average price: $150) that Gerhart had carried for many years. Folding chairs were set up in the store’s foyer. A security guard, who looked like an old Texas lawman with his white hair and handlebar moustache and who usually worked Tiffany’s, stood by the door. Annie Laurie and Milt sat on the front row. Henry slipped to the back and listened as the commentator began his nonstop, sexless atta-girl babble.

“Everybody’s doing blazers, pants are back, silhouettes have changed, skirts must cover the knee. Please notice the slit. They love to show it and we love to see it. White is right. It’s a polyester washable that appears to be linen. Love the season, love the look, love the lady. Thank you, Barbara. All you see, you can buy,” the salesman continued. It was a carnival spiel and it worked. Greg Gerhart later told Henry the store had had one of its best days ever.

After the show Henry said howdy to the security guard and walked toward the University Club for his daily gulp of air and burst of exercise. Henry often ran his five miles—25 laps—on the club’s track, which circled the skylight above the ice rink, then watched some tennis on the club’s ten air-conditioned courts. Club members used the Houston Oaks pool, also on the fourth level, and there was even a lone basketball goal near the entrance to Neiman’s, but Henry had never seen anyone use it. The late-afternoon sun had moved behind the Galleria 2 office towers and now struck the complex a glancing blow. Inside the exclusive club, Henry picked up his running clothes and saw a notice on the bulletin board: “Reward—$500 for return of Rolex watch. No questions asked.” A stolen Rolex? The heavy-jeweled and silent watch that wound itself and ticked on the pulse of every University Clubber? Impossible! He had not seen a member without one. A Rolex was obligatory equipment for a businessman, a badge of success. Lost, perhaps, but not stolen unless someone wanted to wear two.

Out on the track Henry joined the trail of runners with well-preserved, middle-aged bodies, still tough-limbed, their jugular veins standing out as they ended their personal lap assignments. Back in the locker room, he steamed, saunaed, whirlpooled, listened to stock-market talk and Carter-cursing, River Oaks gossip, and the bewailing of excess government interference. Leaving the club, he caught a waft of Szechuan Kung Pao chicken with peanuts.

Refreshed, Henry strolled to Neiman-Marcus, which sat at the end of the Galleria like a huge, imposing bird that had grown great through the years because of its ancestry and fine plumage. It had no need to engage in the endless preening and loud caw-cawing practiced by others. It stood above the rabble and pell-mell retail havoc of the Galleria. It was The Store. Henry’s heart always tingled a bit and he felt a little intimidated every time he entered Neiman’s and walked among the cold, appraising smiles of the salespeople. They were all beautiful, stylish, perfectly coiffed, and seemed bred from birth to disregard a poor wretch like himself.

Neiman’s did not hire harridans. All the salespeople were very competent and made a lot of money. The top ten women in cosmetics, for instance, had each earned at least $25,000 last year. The department had cleared $4 million. Henry had wanted to congratulate the top seller, Donna Petrovic, but she was on leave of absence to become a mother.

Was it not perfect that the Galleria love story of Larry Schatzman and Lisa Ikard should have occurred here, within the most elegant confines of glamour and luxury in all the 1.26 million square feet of Henry’s home? Larry Schatzman had taken over from Lawrence Marcus, Stanley Marcus’s brother, as general manager of Neiman’s in 1977. Schatzman had spent his entire career with the Marcus organization. A track scholarship to the University of Arkansas first brought him to the Southwest. He was a hundred-yard-dash sprinter (9.8 seconds) from Brooklyn who quickly became known as “Yank” at Fayetteville. After college and the Army he began working at the parent store in downtown Dallas as a part-time salesman in men’s shirts and ties. From there he quickly moved up the ladder. After Larry had been at the NorthPark store for three years, Mr. Stanley called him into his office and said, “I want you to be our ambassador to Florida. I want you to open the first Neiman-Marcus outside of Texas in Bal Harbor.” After Florida, Larry became ambassador to Georgia to open the Atlanta Neiman’s, his last assignment before returning to Texas to manage the Houston store.

In size and goods, Houston’s Neiman’s closely resembled the downtown Dallas store, still the chain’s leader in sales. The Fort Worth, Atlanta, and St. Louis stores were similar in size and merchandise. Washington, D.C., a big town for evening wear, featured more couture and Bal Harbor carried more sportswear. The new star was the Beverly Hills Neiman’s, which opened last year and already ranks fourth in the chain (behind downtown Dallas, NorthPark, and Houston), with sales of $30 million, $10 million more than the initial investment. By 1985 Houston would have two more Neiman’s stores— one in the Town and Country Shopping Center and one in the northern part of Harris County.

The Galleria Neiman’s had definitely changed for the better under Schatzman’s direction. He had put a stop to an in-house gang of thieves, led by the head of the store’s security department, that had been stealing stereos, televisions, sportswear, and other items for years in their own “quest for the best.” In the case of a longtime employee who had been stealing expensive perfumes and jewelry (by placing them under the day’s detritus in her trash gondola) he accepted her resignation instead of pressing charges.

Larry was emotional, volatile, and lovable. He worked alongside his employees and made everyone feel more like a family. He had improved working conditions in small but important ways, such as having fresh flowers placed on the employees’ cafeteria tables downstairs in the Miniposa, just as they were in the upstairs Mariposa customers’ restaurant.

In cosmopolitan, dress-up cities like Dallas, Houston, and Washington, D.C., Neiman’s had always successfully mixed moderately priced ready-to-wear clothes with expensive couture lines. In the Galleria, competition for the moderately priced clothes dollar was stiff and fairly evenly divided among several stores, but until recently no one had challenged The Store for the expensive couture clothes dollar. Only Sakowitz, across Westheimer amid a cluster of smaller stores, competed with Neiman’s on a large scale in dressing the city’s wealthiest women, the real thoroughbred clotheshorses in Houston. The couture business in the Galleria area had changed in recent years, however. Not long ago each store that carried the more expensive Paris dress designers’ clothes had had exclusive contracts with certain couturiers and the customer simply shopped at the store that carried her favorite designer’s clothes. But many stores that carried couturier clothing—Saks Fifth Avenue, Lord & Taylor, Frost Bros., Marshall Field, Galleria 2 boutiques like Ted Lapidus—had moved to the area, making exclusives very rare. There were still a few—James Galanos at Neiman’s, Valentino and Yves Saint Laurent at Sakowitz—but couture shopping was no longer the exclusive domain of two or three stores.

This increased interstore competition for the expensive clothes dollar had created star salespeople within each store’s couture department, who developed close, almost doctor-patient relationships with their customers. They dressed them, advised them, knew their bodies and styles so well that they often bought everything for the clients. Don’t come in, we’ll come to you. These VIP salespeople delivered clothes to their best customers’ mansions on weekends, interrupted vacations when a client unexpectedly flew in from Cannes, and hunted down mystery creams and powders. Arthur Cox, director of couture at Sakowitz, once located a badly needed dress in Palm Beach, bought it retail, had it put on a plane (first class, of course), waited nervously while it was fogged in at Atlanta, rushed it from Houston Intercontinental Airport to the buyer’s house, and practically remade it in time for a cocktail with his client before she left at four-thirty in the morning for a party in San Juan. Arthur was Sakowitz’s star.

At Neiman’s, it was Sylvia Goldstein. Sylvia didn’t even have a Social Security number when she followed the advice of her sister, who worked in cosmetics, and started out in Neiman’s couture department eight years ago. Now she was the number one couture salesperson in the entire Neiman-Marcus chain. Besides dressing her wealthy clients, Goldstein kept a watchful eye on the designers’ visits and their fashion shows. These events began in August, usually with Andre Laug (daytime dresses at $1200), then Geoffrey Beene (whose clothes had increased in price from about $350 three years ago to about $1200), on to Bill Blass, Karl Lagerfeld’s Chloe collection, and finally, in September, the most expensive and finest of American designers, James Galanos, who was considered the equal of the great Paris couturiers. Galanos’s clothes ranged from $5,000 to $15,000.

Carolyn Farb was one of the most consistent buyers in Houston’s stable of aristocratic clotheshorses and one of Sylvia Goldstein’s top clients. Married to her third husband, builder and sometime singer Harold Farb, Carolyn was making waves in the Houston social world, shooting for the starry firmament that included Lynn Sakowitz Wyatt and Joanne King Herring. The catty chanted, “The only sound at night is Carolyn Farb climbing,” but last spring she won the hearts and minds of many critics by raising more than $200,000 for the city’s ballet company with her hard work. Carolyn used to prefer YSL at Sakowitz. Now she favored Blass, Galanos, and Chloe and Frank Olive’s hats and was one of Sylvia’s star customers at Neiman’s. Arthur Cox still had Lynn Wyatt and seven or eight others to keep him busy.

Besides the wealthy shoppers, Sylvia and Arthur had to contend with the lonely rich, the obsessive shoppers who had found their raison d’être in Neiman’s or Sakowitz’s clothes departments. Judy, who was tall, thin, and always wore sunglasses, came to the store every day to be assured once again by the sales staff that she looked wonderful. She spent only $10,000 a year, not much compared to the stable’s average $80,000 per annum, but she needed friends more than clothes. Often she brought the ladies sandwiches for lunch, finally choosing a belt or hat before heading home. Another woman who came in almost as often suffered from the Alter Syndrome. No matter how nice it looked, the dress she bought had to have its hem raised or lowered, had to be changed in some respect for attention’s sake.

Selling couture and fancy ready-to-wear were the hardest jobs in the store. Sylvia and her staff had to know thoroughly a customer’s structure and appearance as well as her psychological makeup. Was there a limit to the number of $10,000 dresses a woman would buy and not feel distressed that the cost of her covering equaled half the yearly income it took to maintain a family of four? This was where Lisa Ikard began her career at Neiman’s.

When Lisa started working in Sylvia’s couture department as a “part-time shopper” (one who helped dress the rich), she was married to Bill Ikard, a young, ambitious lawyer whose father, Frank Ikard, presided over the powerful American Petroleum Institute in Washington. Lisa was a striking woman. Her coiled energy always seemed on the verge of erupting, and her beauty never failed to transfix men and women alike. She seemed a natural for the store’s public relations position, and not long after she came to couture, Lisa relocated in that job, fifty feet from Larry’s office.

Many years ago, at the beginning of his career at Neiman’s, Larry had married a Dallas woman. They had three children: a son who had recently graduated from Harvard and two teenagers. Larry’s wife and children were remaining in Atlanta until the completion of their new home in Houston, which was being built not far from the Galleria. Meanwhile, Larry and Lisa began attending store functions together. They were a delightful couple— the handsome, graying, well-groomed representative of Texas’ most prestigious department store and the beautiful, lively golden girl. They were a frequent item at Tony’s and Rudi’s and often lunched at the New York Deli across the street. Soon the inevitable happened. They parted spouses and moved into the Galleria Plaza Hotel until Larry found his down-the-street townhouse. Not long after, Lisa’s ex-husband, Bill, married Kathy Cronkite, daughter of Walter. Lisa resigned last August and now a photograph of her lovely face beamed at visitors from Larry’s desk, not far from his album of Harold Farb songs. Larry did not fill the public relations job until February, six months later, when he hired Debbie Cordingly, a beautiful young woman who had done P.R. work at élan, one of the city’s nicer singles clubs. While working at élan, Debbie had met a Larry, the then-married Larry Siegel, one of the partners who ran the club. Debbie and her Larry had married in April and honeymooned in Mexico. The symmetry of it all was delicious.

While Henry P. waited for Monica to join him for the Mariposa’s evening buffet, he counted the light bulbs on the arch (133) and listened to the storewide bing-bing-bing paging system that summoned department heads to their telephones. He studied the overhead metal tubing that once had been covered to simulate a butterfly (mariposa is Spanish for “butterfly”). Two male employees conducted a quiz near his small table.

“What was Greta Garbo’s first spoken line in the movies? Come on now, maybe this will get you out of your Casablanca rut, for God’s sake. Give up? ‘Gif me a viskey, ginger ale on the side—and don’t be stingy, baby.’”

Sighing, Henry wished his friend would arrive. It would be their last time together. He had been gently talking to her about changing professions, but Monica would have none of it. She planned to move west in a few weeks to the Century Plaza in Los Angeles, the only Western International hotel to exceed the Houston Oaks in overall profit and second to the Oaks in profit per room. No one could ever accuse golden-legged Monica of being a careless businesswoman. Based on what he knew about her profession, Henry guessed her life probably would not end well and he felt sad. She was a good woman. He wished he knew some way to save this wayward moth from her deadly candle.

“Henry-P-Upchurch, I’m tired and my day’s just begun,” Monica exclaimed as she joined him in the restaurant. “Let’s get out of here.” She marched through cosmetics, out the entrance under Neiman’s clock, and back into the Galleria. They walked the whole mall, stopping only at Video Concepts to see a snippet of Robert Redford in Three Days of the Condor on the six-foot screen. Finally they returned to the dark bar of their first meeting. Her bare, sunburned arms rested on the table. Henry bet she was the only woman there wearing Bal à Versailles perfume.

After a long silence she looked at him. “Don’t say anything. I’ll probably be leaving in a minute and I want to say good-bye. I’ll miss you, Henry-P-Upchurch.” A tear ran down her cheek like a drop of rain down a leaf. Henry was about to reply when her purse beeped. He never saw her again.

At three in the morning, Steve Miller’s rock ’n’ roll boomed around the mall near the ice rink. Sweepers pushed the Galleria’s daily flotsam into piles. Moppers trailed the sweepers. Strollers held hands and gazed absentmindedly into store windows at mannequins whose arms were thrown out in frozen gestures. At A Slice of Life on Level Two above the rink, the large blade, scissors, cap lifter, and can opener of a huge red Original Swiss Army Knife moved silently up and down in the window. Henry gazed down at the blue veins in the ice while overhead the reflection of the Italian Christmas tree lights gave the Galleria a permanent terrestrial constellation, a dazzling eternal zodiac. Henry walked on toward his bedroom at the Galleria Plaza and thought of the waiting Frango mints and his friend Monica and wondered why the Sunday New York Times cost $2.75 at the Fifth Avenue News and $3 at the hotel.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Houston