Leon Coffee, perhaps the most revered and beloved clown in the history of American rodeo, had already had about enough of my crap well before I led a rank and irate fighting bull named Ghostbuster directly to the spot near the arena wall where Leon was catching his breath. I was running, as the real cowboys present that day liked to say, “pie-eyed”—in other words, scared witless—and Ghostbuster, a big gray Brahman with an ugly black hump, was about five feet behind me and closing in, kicking up dirt clods, slinging bull snot, and bellowing like the fiery furnaces of hell. Somebody was going to get messed up, no question about it, and my only thought was that I needed to get up and over that wall. Unfortunately, that wall was right by Leon.

This was not the first misstep of my twelve-hour-old career as a rodeo clown, although it was the one fraught with the most risk to human life. It was two days after Christmas, 1988, and I was Leon’s lone remaining student at a rodeo school in Wichita Falls he was running with Butch Kirby, a former world champion bull rider who was teaching four students of his own how to ride. I was the only college boy enrolled, a kid from the suburbs whose sum total exposure to things country consisted of dipping snuff, watching The Dukes of Hazzard, and listening to Hank Junior when I went muddin’ in my Toyota pickup. I was between semesters my senior year at the University of Texas in Austin, with no clue what to do after graduation nor any realistic sense of what I couldn’t. I figured that my history degree would be no greater hindrance to a rodeo career than anything else, so to the rodeo I turned.

The bull-riding students, on the other hand, had their rodeo bona fides. There was an area shop teacher who’d won $19,000 that year riding bulls and a seventeen-year-old high school kid from Vernon who wanted to ride bulls so badly he’d told his disapproving mother he was going hunting for the weekend. One cowboy drove his wife and Border collie all the way from Virginia in a little Corolla, sleeping in the car in hotel parking lots along the way. These guys had all actually tasted real rodeo, even if it was just one great ride, and they had to have more. I was the only one without a hat.

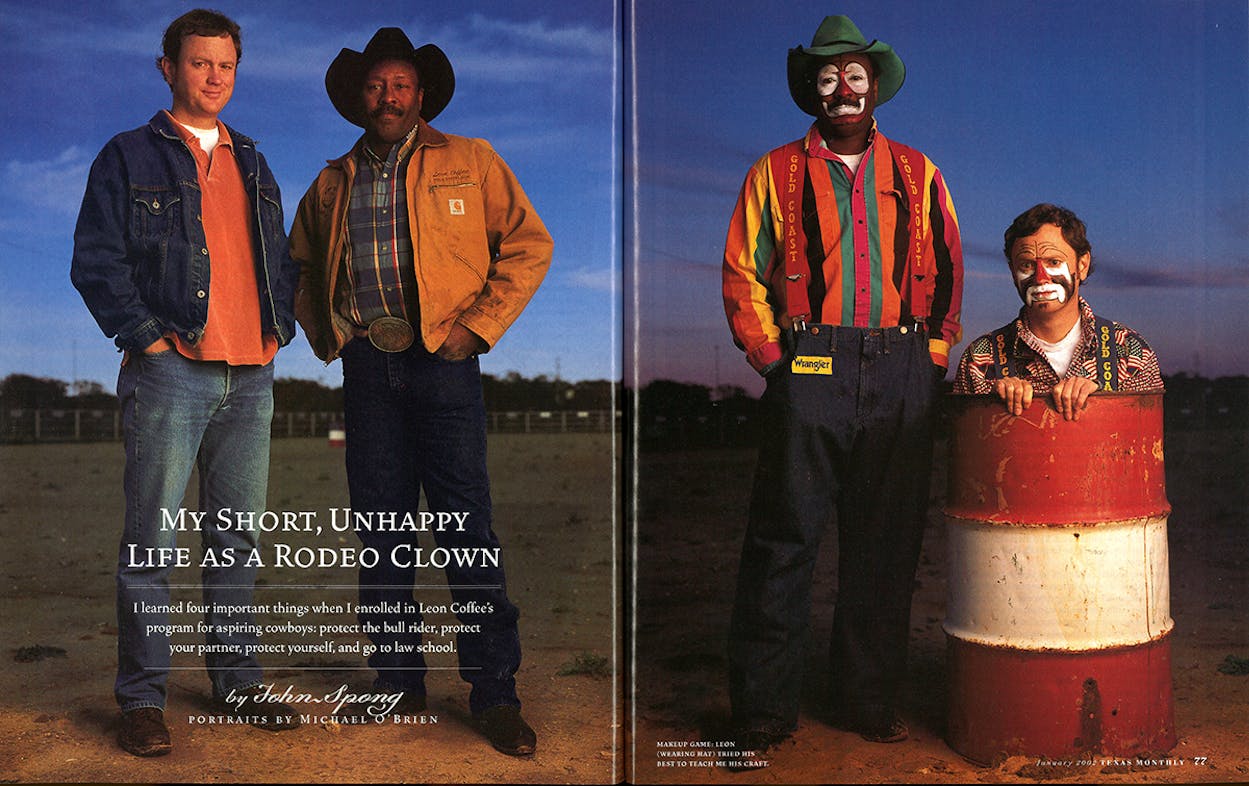

And then there was Leon. Though he stood barely six feet tall counting the tall foam crown of his gimme cap, he towered over the bulls and the rest of us. His constant popping off was the soundtrack of the three-day tutorial, and his dances with the bulls were hands down the highlights. While the cowboys insisted on calling him a bullfighter—as if the word “clown” was somehow demeaning—Leon was sure enough of what he was doing that he didn’t need to split that hair. “Do I wear makeup, and am I funny?” he asked. “Well, I guess you’d have to call that a clown. And am I one badass, bullfighting sumbuck? Why don’t you tell me.” The paraphrased piece of Scripture that he suggested I turn to when things looked bleak with the bulls summed him up to the letter: “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for I am the baddest cat in the valley.”

His “school” entailed more lab work than class time. All we received in the way of a lecture was two hours in a hotel room at the Wichita Falls La Quinta watching bull rides from that year’s National Finals. Butch and his students sat on one side of the room talking about the bull riders, and Leon, a man from Oklahoma named Tom, and I talked bullfighting on the other. Leon didn’t instruct us on applying makeup or telling his favorite manure jokes or diving into a barrel; this was about protecting cowboys, and the real education came in the arena. The student bull riders needed the student clowns to take care of them when they sailed off those veteran bulls. By the time I reintroduced Leon to Ghostbuster, I’d firmly established that I wasn’t up to the task.

I hung back too far from the bulls after they left the chute. I wasn’t able to turn them around when they spun into the cowboy’s riding hand, a most severe failing on my part because it greatly enhanced the likelihood that a cowboy would get hung up or stomped. When a bull carried a cowboy out away from the chutes, I was too slow to keep up, and when a cowboy actually hit the ground, I was entirely too willing to let Leon be the one to get between him and the bull. I’d even worn the wrong shoes, turf cleats that clodded up with that soft arena dirt, rather than the standard baseball cleats that might have provided some actual traction. Lucky for me, not to mention the cowboys, Leon picked up the slack.

Which struck me as a good deal for everybody. Leon was 38 years old, 15 years into a career that continues to this day, and his name was already carved into the pantheon of the great American rodeo bullfighters: Quail Dobbs, Rob Smets, Miles Hare, Rick Chatman, and Leon Coffee, all immortals in an art form borne of fragile mortality. The bull riders whose hides he saved night in and night out loved him, as did the fans in the stands and the kids in the schools and the hospitals he visited at stops on the pro rodeo tour. He was fast, fearless, and wonderfully full of beans in a profession where men who wanted for any of the above would at best be forgotten. At worst they’d be killed.

But Leon hadn’t planned on fighting any bulls this particular trip. He was fresh from arthroscopic surgery on his right knee earlier in the week, and he’d expected his two pupils to do the work. That would have been me and Tom, except that at some point in the night after his initial meeting with Leon and the livestock, Tom had rethought his commitment to the craft and taken himself back to Tulsa. Leon was pressed into duty.

Neither of which, the desertion nor the knee, was exactly my fault. But there was more in the mix. Leon groused about a poor night’s sleep in our classroom-dorm. Apparently my questions the previous afternoon regarding his time in Vietnam had him dreaming all night about Viet Cong. Matters weren’t helped by whoever it was in the room, presumably me, who had been a little gassy in the night.

And then there was the fact that I just wasn’t very good at being a rodeo clown, although if Leon had thought back to our introduction that spring, he might have been less surprised. Too many beers at the Travis County rodeo had inspired me to approach him after the show and tell him I wanted to be a bullfighter. He asked about my experience, and I admitted I had none but assured him that everybody where I worked thought I was pretty crazy.

“Uh-huh, it would help if you were pretty fast too.”

“I’m really more sneaky-fast than fast-fast.”

“Right. Look, son, I really don’t think you want to do this stuff, but if you think you do, here’s what’s got to happen. You’ve got to go to the drugstore and get yourself a big bag of marbles. Then you take that bag of marbles with you to every rodeo you can find, and you tell them you’re a bullfighter and ask them if they’ll let you work.”

“Can I tell them I talked to you?”

“No-no. If you give them my name, I will hear about it and I will find you, and you do not want that to happen, you hear me? So you find these rodeos. And we’re not talking about the Stockyards and the Astrodome. We’re talking about Friday night bull rides out at the Sheriff’s Posse Arena on the road to Lockhart. You know where that’s at?”

“Yessir.”

“Okay. You have to go to those rodeos and you put a handful of those marbles in your mouth and you work bull after bull after bull. Are you listening to me?”

“Yessir.”

“And every time you get hooked . . .”

“What’s ‘get hooked’?”

Leon’s laugh was high-pitched and hoarse. “Oh, man, you’re going to find out what that means quick enough. Believe me, you will find out. And every time it happens I want you to spit a marble into the dirt where you landed. And I want you to look at where that marble lands. I want you to study it. Then you’re going to get up and go again. Once you’ve done enough rodeos and gotten hooked enough times that you’ve lost all your marbles, if you still want to be a bullfighter, you give me a call.”

He could not have intended for that pat response to be taken seriously, and if he doubted my resolve, he should have come out and said so. I took up jogging, watched a bunch of rodeo on television, and six months later, when I found Leon’s name and number in an ad for the school at the back of the ProRodeo Sports News, made that call. When he cashed my $375 tuition check, our rapport was cemented, and I had my mentor. Kind of like Yoda.

I turned myself over to him completely when we got to Wichita Falls. I hung on his every word as we watched those tapes in the hotel. I studied his moves to juke the bulls. There was the T-Step, the tight circle he ran inside the bull’s shoulder. There was the Step-Through Maneuver, an exaggerated fake to one side then a spin back around that ended with the clown waving bye-bye to the passing bull’s haunches. I memorized the order of a clown’s priorities: protect the bull rider, protect your partner, protect yourself.

That was Leon’s mantra, one of the first things he tried to impress upon me and one drummed into my head between every ride. A clown never leads the bull back to the rider. When the bull rider or your partner is in trouble—when he has been hooked and is down or when he’s backed up to the wall—your job is to “capture” the bull, or get him to fix on you, and lead him the hell away. Leon emphasized an absolute duty, always and everywhere in that rodeo arena, to protect the other cowboys, to dart between him and the bull, to come in so close to the bull that you could slap him on the head to make sure you had his attention.

What you absolutely do not do, he added for clarity’s sake, is lead the charging bull back to where the cowboy is stranded. Least of all if he’s near the wall. Get the bull out in the middle of the arena, where he can stomp his two thousand pounds of rampage and menace into dirt rather than bones. Let him wave those horns like baseball bats in the air, not into somebody’s kidney. Remember the mantra: the bull rider, your partner, yourself.

It was writ large on Leon’s astonished face when I ran, pie-eyed, right up his back at the arena wall with Ghostbuster close behind. The bull had just chased Leon to the left of the chutes where Leon had hoisted himself up onto the wall, teetering on his hips atop the five-foot-tall barrier, exposing the back of his legs for nice, clean wishbone breaks. But Ghostbuster, noting the ease with which Leon had sidestepped a couple of his rushes and then scampered to the perimeter, rightly surmised that one of the clowns out there knew what he was doing. The bull turned 90 degrees to his right, where I was standing more flat-footed spectator than bullfighter, and full bore he barreled ahead. I, of course, took off immediately for the wall, and just as Leon hopped down to the ground, I arrived, about two feet away from him. In unison we jumped from the bull to balance on the wall.

The problem was, that section of the arena wall wasn’t wall at all. It was quarter-inch steel cable strung like a tall barbed-wire fence, with three-quarter-inch sheets of plywood hanging from the second highest strand. Picture two birds on a wire, side by side, but they weigh about 180 pounds apiece, and one of them is no more nimble than an overfed basset hound. I had enough work just hanging on, but I also had to bounce my legs off the plywood to dodge the bull each time he crashed forward. When a lunge by Ghostbuster drove my right foot clean through the plywood, instinctively I looked to Leon for a little sympathy.

That was bad move number twenty, and by this point, Leon was ready to make something happen. He rolled over the fence and out of the ring with me right behind him, and we ran fifteen yards to the corner of the arena. “We’re going to fight this cat here. He’s a bad little dude,” Leon said. He climbed the back of the wall, but Ghostbuster had followed us down the fence line and was waiting right there. Leon hollered at the cowboys by the chutes to get the bull’s attention. They whistled, waved their arms, and yelled, “Hey, bull!” but Ghostbuster kept eyeballing Leon, who backed down and ran along the ring to where we’d hopped over. Ghostbuster stayed in the corner.

That’s when Leon shifted gears. He leaped into the arena, caught the bull’s eye, and ran straight at its right ear. As the bull dove forward, Leon cut hard to his own right, turning a tight loop near enough to the bull to yank coarse, greasy hairs off that nasty black hump, the bull spinning wildly around him until Leon slid to a dead stop and froze the beast; he changed direction on his bad knee and laughed at Ghostbuster as he skipped off on the good one. “What’s wrong with you, big’un?” Leon said. “You better go get your daddy ’cause you ain’t bad! No, sir!”

In barely four seconds, half the time of a completed bull ride, Leon had proved up his legend. As precise as a point guard and as cocky as a surgeon, he had moved like he had a crowd of 10,000 people watching. The only distinctions between this and real rodeo were that his theme song—Michael Jackson’s “The Way You Make Me Feel”—wasn’t playing and he wasn’t in costume—no makeup to hide his grit, no floppy green hat to hang on the defeated bull’s horns.

Now, my turn. I was a little slower into the arena. Carefully, deliberately, almost reluctantly, I sashayed to ten feet in front of the bull, a tentative step one, step two, step three, and then Ghostbuster made his move. He charged at my right knee, and I pivoted quickly to get around him, but he’d stopped and was waiting for me when I completed my turn. We were face to face. There was a pause, and he looked over at Leon, allowing me to backpedal two soft steps while I considered the right move. It was the T-Step. I took off for his left ear. “Go around him,” yelled Leon repeatedly. “And take your feet with you!”

I made my way past the bull barely a half-step from his horns, taking a rough nudge in my side and slipping momentarily to one knee as he whirled with me, but keeping my head and pushing on until, at the turn of a full revolution, he laced one big heavy horn down around my left hip and cocked his head back into his shoulders, sharp and short. Suddenly I’m a goalie on a foosball table, spinning through the air, legs spread wide for a cartwheel but no hands on the ground to manage my descent. I crashed hard on my left hip. Lucky for me, Ghostbuster let me hobble off without further incident, because Leon was laughing way too hard to provide any help. “Welcome to my world!” he hollered.

I chose not to ask about his vaunted priorities as he laughed through our lunch. I knew he would have gotten to me if he thought Ghostbuster had anything in mind once I wrecked. I nursed my wounds over a truck-stop hamburger and replayed the showdown in my head. With each viewing the rout grew more one-sided and my hipbone more painful, until I started to have, for the first time in my life, concrete thoughts about the future. Maybe the summer after graduation would be better spent studying for the LSAT instead of rodeoing. If I could get into a good law school, I’d still be able to talk about “my rodeo clown days” during job interviews at law firms and on the dates I’d finally land with sorority girls.

But Leon was back on my side. He told me I was coming along. He pointed out that Tulsa Tom hadn’t been able to stick it out. He invoked the baddest cat in the valley. I had to give it one more shot.

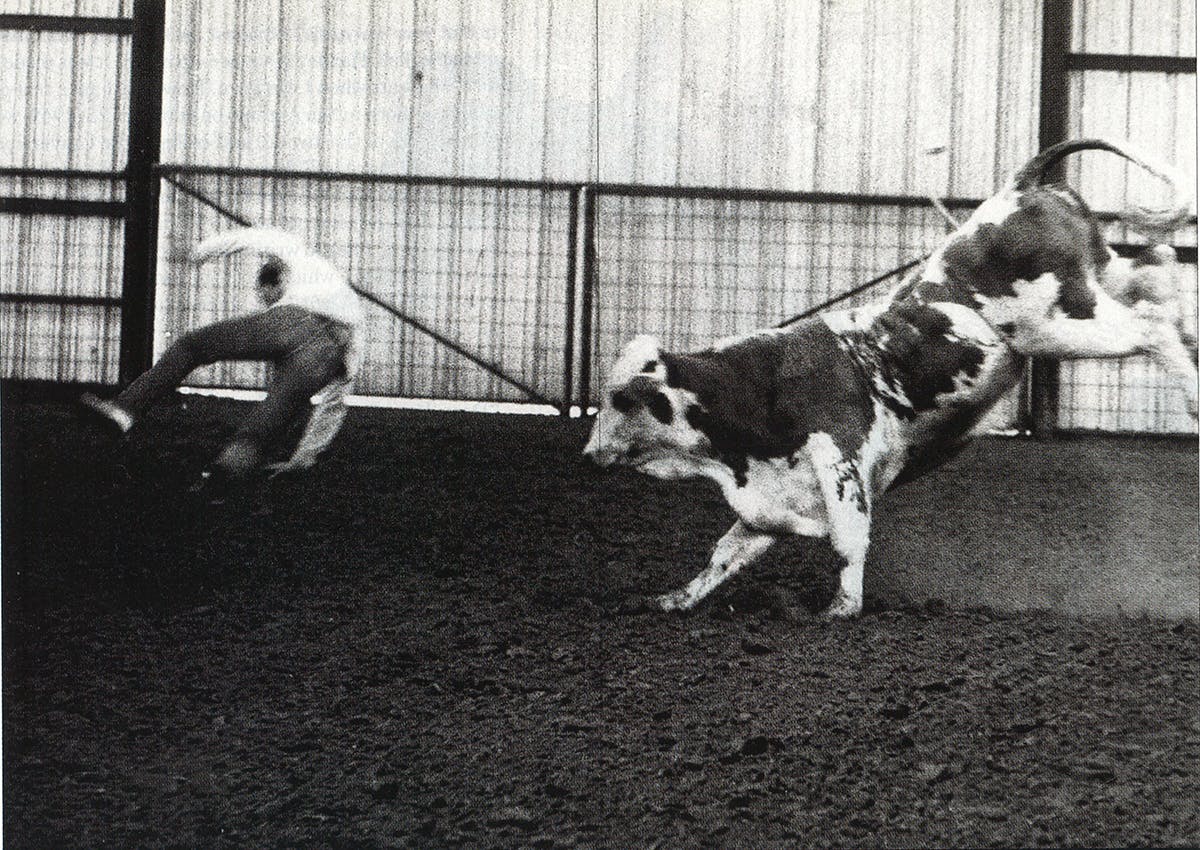

“One last shot” would have been more apt. My encounter with a brown-and-white Simmental bull named Pretty Boy, the biggest bull in the arena, was a greater debacle than my battle with Ghostbuster. A poorly executed Step-Through Maneuver resulted in a head-on collision. With Pretty Boy approaching at about thirty miles an hour, I was intent on waiting until the absolute last moment to make my fake, but unfortunately that last moment was spent contemplating which direction to juke, rather than actually juking. In an instant I was stationary, then flying, then landing some thirty feet away and rolling onto that same blue-black hipbone.

It was still tender twenty months later, on my first day of law school.