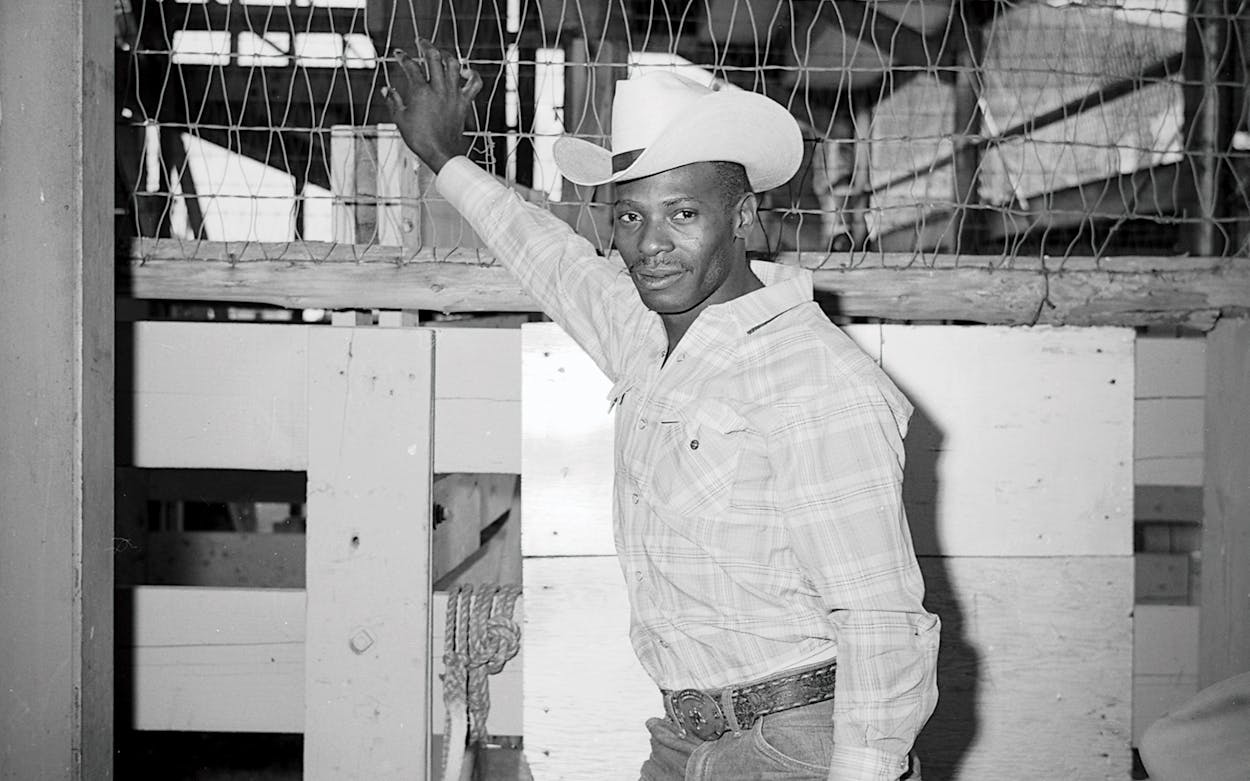

By 1972 Myrtis Dightman was, by rodeo standards, past his prime. He was 37 years old, an age at which most cowboys have hung up their spurs or at least wisely considered doing so. But the bull rider from the East Texas town of Crockett was still in the thick of things, having just qualified for his seventh—and last—National Finals Rodeo.

Dightman’s first trip to “the Super Bowl of Rodeo,” eight years earlier, had been historic: it marked the first time a Black cowboy had ever competed at the NFR. But the man dubbed the Jackie Robinson of Rodeo never won the NFR’s gold buckle—not during his first six trips there and not during his final appearance, when he placed seventh. As a younger man, he would almost certainly have been crowned the world champ, had blatant racism not hindered his efforts.

Yet Dightman’s legacy has grown far beyond the import of any trophy in later years. He ended his career in 1988, at the inaugural Myrtis Dightman Hall of Fame Rodeo; became the first living African American to be inducted into the National Cowboy Hall of Fame; and is the subject of a new documentary, Spurring Change. A feature film about his life, with fellow Texan Jonathan Majors attached to star, is in development. But Dightman doesn’t carry himself like a celebrity or a man who endured terrible injustices. Most days, you can find him sitting on his porch in Crockett or having lunch at the Cattleman’s Country Cafe. He doesn’t dwell on the grievances and tends to shrug off the accolades. He’ll tell you, “I’m just a cowboy.”

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Jackie Robinson of Rodeo.” Subscribe today.