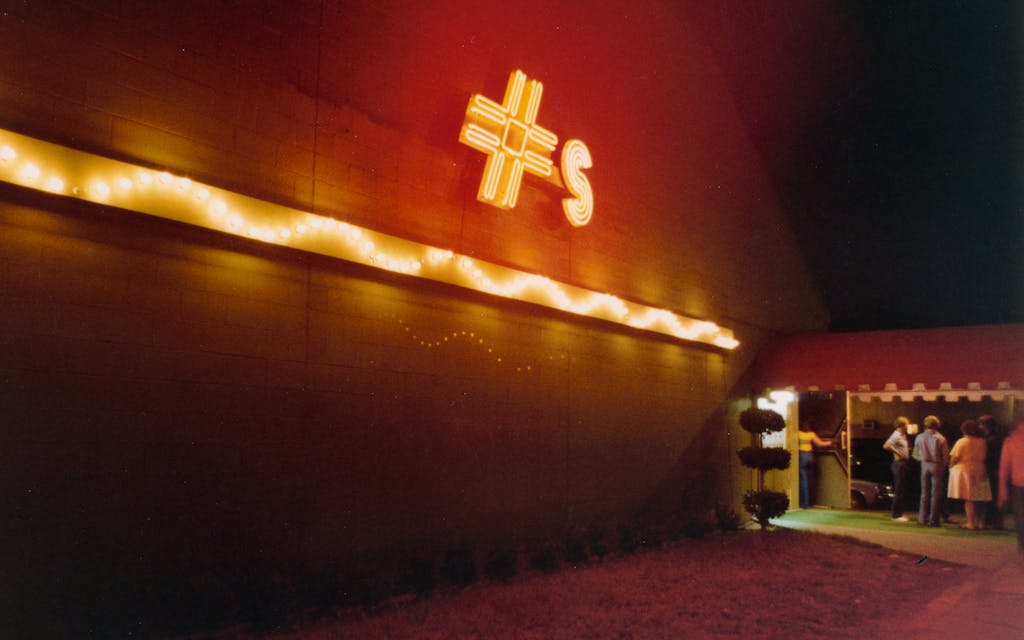

On a recent Friday night, a steady stream of revelers lined up at the intersection of Westheimer and Mason in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood, their foreheads beading with sweat from the July humidity. Each guest waited for their turn to step into the doors of the illustrious Houston nightclub Numbers, which reopened in late May after shuttering in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Inside, hundreds of partygoers—some masked, others not—swayed to the sounds of Classic Numbers, a long-running dance night where resident DJ Wes Wallace has bumped new wave, goth, punk, and industrial songs for decades.

At the cavernous club and venue, visitors can lounge on glowing neon-green cubes that seem plucked from the eighties cult film Repo Man; bust a move onstage; throw back a tequila soda for just a few bucks; and smoke on the spacious patio under the watchful eyes of Siouxsie Sioux, David Bowie, and Trent Reznor, whose likenesses adorn a mural on one side of the building. While all of those features are a blast to experience, they aren’t what makes this place special. Although Numbers has evolved over the last four-plus decades in its various incarnations, including as a dinner theater and a gay disco, one core tenet has remained the same: people can be themselves here.

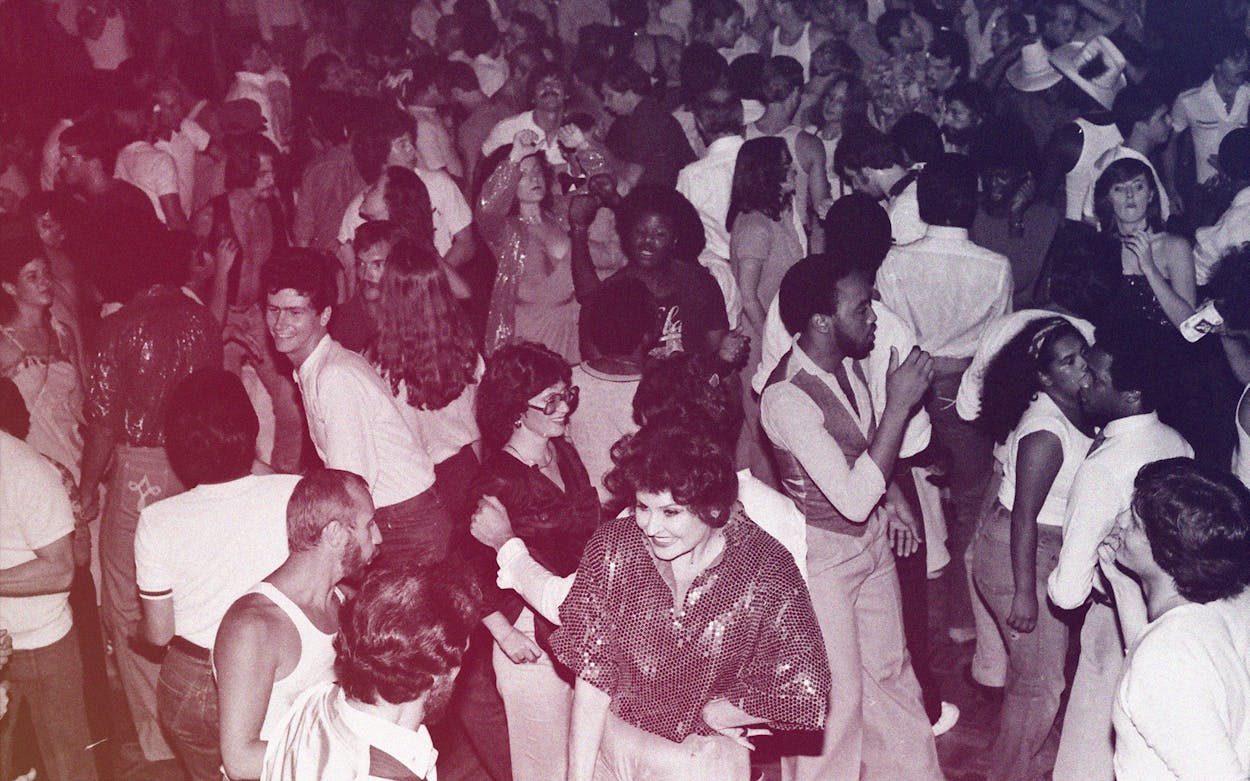

It’s a story deserving of the big-screen treatment—and a new documentary chronicling Numbers’ many lives, and how it’s existed as a locus amid social and civic change, premiered on July 31 in Houston after being in the works for nearly ten years. Friday I’m in Love, which melds personal narrative with fascinating history, is told through the testimonies of the hardworking employees who have kept the place going, as well as longtime regulars and musical and drag luminaries who have performed there over the years. We also time-travel through grainy archival videos—and, of course, there’s plenty of B-roll footage featuring shimmying and hip-shaking. Ultimately, the film is a celebration of a place that is both a world unto itself and could only exist in Houston. As one interview subject, Asa Greene, puts it in the documentary: “Where else can you dance next to a seventy-year-old guy in a thong and a schoolteacher, a bunch of goths?”

Fittingly, someone who found communion underneath the glimmering disco ball directed and narrated the documentary. Filmmaker Marcus Pontello (who uses they/them pronouns) draws viewers in at the beginning of the film by detailing their upbringing in Pearland, a conservative suburb south of Houston, where they felt like an outsider. The first lengthy sit-down interview is with Pontello’s mother, who recalls her middle-schooler’s habitual weekend trips to Houston’s historically queer neighborhood, Montrose. There, Pontello would sift through racks of thrift-store clothing at the likes of Buffalo Exchange and Wear It Again Sam. Later on, their mother started dropping Pontello off at Numbers, at first worrying about letting her fifteen-year-old attend concerts and dance parties at a nightclub. But Pontello’s mom eventually realized that “it was a place where you could have a good time and be with people of all kinds, and nobody was hurting each other, nobody was being mean to each other . . . They don’t judge; that’s why you go there. And that’s how life should be.”

Pontello eventually moved away from Houston and studied theater in Los Angeles, but Numbers’ impact always remained top of mind. In the fall of 2012, despite having no formal training in filmmaking, they had the idea to create a documentary that would unpack Numbers’ personal importance to countless Texans and dig into the club’s past. “There is a real, real, real heartfelt connection to this place that I and a lot of people experience,” Pontello tells Texas Monthly. “So I wanted the film to be more than a music documentary.” Assembling a small team, Pontello learned on the job about cinematography techniques and lighting; sifted through a trove of public news archives at the Houston Public Library; and tracked down important figures in the club’s history—including the building’s original owner, the late Beverly Wren, who first opened the space as the dinner theater locale Million Dollar City Dump, in 1975.

Around that time, anti-LGBTQ crusader and singer Anita Bryant launched a nationwide tour against gay rights. When the Texas State Bar Association invited Bryant to speak in Houston in June 1977, thousands of queer residents marched together downtown in protest. “After we did the rally, suddenly there were lesbian couples and gay male couples with their arms around one another that would never have made such a public statement in their lives,” says Ray Hill, an LGBTQ activist, in the film. “We had told them the truth: Come out of your closet just this one night, and you may never go back in . . . the gay community had changed from the part of town where the bars are to a large group of people with common goals and aspirations that felt a bond toward one another.” Known as Houston’s Stonewall moment, the Anita Bryant protest catalyzed residents to launch the city’s first-ever Pride Parade, which ran along Westheimer for decades before relocating downtown.

Million Dollar City Dump reliably attracted crowds every weekend, with audience members cheering for Las Vegas–esque (and, as was once advertised in Texas Monthly, “Parisian”) revues. But it was pretty empty on weekdays, and Wren found herself searching for new ways to bring in customers. Show producer Breck Wall, who cut his teeth hosting burlesque shows in Dallas in the late 1950s and worked with the likes of Liberace and Frank Sinatra on the Vegas Strip, gave Wren an idea: open a gay disco. “I was not acquainted in the gay community,” Wren says in the documentary. “But it sounded like fun.” After redesigning the club, Wren decided to give Wall’s idea a try and reopened the venue as Numbers (the moniker nodded to both a gay novel and a pornographic magazine of the same name) in 1978. Resident DJs and drag performers instantly drew big crowds, including future owner Rudi Bunch. “The seventies was not an easy time to grow up gay,” Bunch says. When he walked into Numbers for the first time, he felt at home. As Bunch explains in the film, queer culture in the pre-internet era was often centered around bars. There, people could “socialize and be themselves and hook up, have political discussions,” he says. “[Bars] played a key role in the gay community.”

Wren ran the club until 1980, but unfortunately the new management didn’t pay the bills and the city shut it down. Later that year the space reopened as Babylon, and featured the musical stylings of Bruce Godwin, a local DJ who started the massively popular New Wave night at the club and spun new tracks that came through the Record Rack, the store where he worked during the day. At the time, musical tastes were more divisive, as Godwin remembers—but at Numbers everyone was welcome. “I had no qualms about being completely gay and loving heavy metal music, being completely gay and loving to watch drag shows, loving to go pogo to the Ramones,” he says in the film. In his DJ sets and later as a co-owner of Numbers, Godwin strove to unify revelers and open their minds to new styles of music.

When a chance cancellation at a nearby venue allowed Godwin to book Siouxsie and the Banshees at Numbers, he realized that he could invite talented musicians to perform there before they hit stadium-size stages. Dozens of luminaries went on to deliver memorable sets at Numbers throughout the 1980s, including R.E.M., Grandmaster Flash, Iggy Pop, and Marianne Faithfull. Many groups returned to perform there over the years, thanks, in part, to the club’s homegrown hospitality (the documentary has a charming photo of Godwin taking Björk and the Sugarcubes to NASA). With eventual co-owner and DJ Robert “Robot” Burtenshaw’s idiosyncratic homemade videos, which were projected over the dance floor many a night, and the fact that Numbers catered to all without the pretension of velvet ropes and a dress code, the club became a local institution. When it suddenly closed in 1987 due to issues with previous management, Godwin and Burtenshaw bought the club themselves, reopening that same year.

Numbers has been no stranger to tragedy over the years: during the AIDS crisis, dozens of employees, friends, and frequent guests of the venue died. It wasn’t uncommon for queer people in Montrose to be subjected to harassment and hate crimes, particularly in the early 1990s. Burtenshaw, a beloved and critical figure within the club’s orbit, took his own life in 2013. “That was a big devastation to Numbers and the people that worked there,” Pontello says.

But as the documentary makes plain, the strength of the community this hub has fostered over forty years has helped it—and the partygoers who find salvation within its walls—survive. And Numbers’ future looks bright, as evidenced by the fact that its nightly parties are still replete with merriment and joyful dancing. “What Numbers represents—aside from its wild and colorful history—is timely,” Pontello says. “There’s a sense of almost radical acceptance at Numbers. Numbers has, and still does, emphasize that in a bold way.”

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Documentary

- Houston