What are you gonna do? Norah Jones asks that question a lot. Not dismissively, but with an implied shrug. It’s something she’ll tack on to the end of a thought when it becomes clear that your perception of her doesn’t neatly square with what she wants to say or, more pointedly, what she wants to play. She knows that plenty of folks are disappointed that she’s refused to record carbon copies of her first album, the one that made her an overnight star. People say her career has been too listless, her catalog too directionless. They’ll make a Starbucks joke. Call her Snorah Jones. But she won’t wince or take offense. She’ll just ask, What are you gonna do? And the answer is, Norah Jones is gonna do whatever Norah Jones was gonna do anyway.

Jones realized early on that she’d never again make an album as wildly successful as 2002’s Come Away With Me, which spun off the hit single “Don’t Know Why,” earned eight Grammys, and has sold more than 26 million copies, achievements she’s always seemed uncomfortable with but not ungrateful for. In fact, her artistic output over the past decade or so has been largely defined by her reluctance to let that album define her. If most young artists in her shoes would have bowed to the pressure of trying to make lighting strike twice, Jones embraced success as a license to jag left. “I saw myself as suddenly having the freedom to try anything,” she says. And indeed, over the ensuing years, she’s leaned into country with her side project the Little Willies, dabbled in punk rock with El Madmo, and collaborated with the likes of Ray Charles, Ryan Adams, the Foo Fighters, and Belle and Sebastian. On her last solo album, 2012’s Little Broken Hearts, she worked up a set of atmospheric electronic pop that bore the fingerprints of oddball producer Danger Mouse. As her reputation as a musical adventurer grew, so did the likelihood that not repeating the success of Come Away With Me would become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But now Jones is in a weird spot. She’s made a record that, initially, feels like a sequel to Come Away With Me. Her label, the legendary jazz imprint Blue Note Records, announced the album with a headline that left little to the imagination: “Norah Jones Comes Full Circle With Day Breaks: 9-Time Grammy-Winner Returns to the Piano & Her Roots.” That press release went on to call the record a “kindred spirit” to Come Away With Me.

The marketing campaign isn’t off base. For the first time in years, Jones wrote the bulk of her new songs on piano, not guitar, and the Norah Jones we hear on Day Breaks returns us to the image of her we’ve clung to: she’s at the piano and the songs are low-key variations on jazz and mid-tempo pop.

“That’s just who I am as a musician. It’s my sweet spot,” says Jones, who grew up in Grapevine and moved to nearby Dallas at fifteen so she could attend Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts. “When I played jazz in high school and college, I was always better at the ballads or mid-tempo material. And the piano is definitely my instrument. When I play it, I gravitate toward a certain type of sound because it’s what I’ve always played on it—jazz or blues. And when that’s stripped-down and mid-tempo, you get something that definitely hearkens back to my first record.”

Hearken it may, but Day Breaks is also a very different record. In 2000, not long after Jones left Texas for New York City, she had her first meeting with Blue Note president Bruce Lundvall. He listened to a demo she played for him that consisted of two jazz standards and a pop-leaning tune her friend Jesse Harris had written. “Bruce said, ‘This is great. But there’s two different sounds here. Do you want to be a jazz singer or a pop singer?’ ” Jones recalls. “I was sitting at Blue Note and I’m not an idiot. So I said jazz singer.” But the album she ended up recording for Lundvall was a pop album—admittedly, a pop album with jazz touches and some impressive jazz players making guest appearances, but one that was closer to the slow-burn balladry of Aretha Franklin or Carole King than to the improvisational stylings of Sarah Vaughan or Billie Holiday. “I didn’t think of it as a jazz record,” Jones says.

Day Breaks, by contrast, really is a jazz record. There are covers of Duke Ellington and Horace Silver tunes, long passages that seem improvised, and a backing band that’s an all-star jazz wrecking crew: drummer Brian Blade, organist Dr. Lonnie Smith,* and saxophonist Wayne Shorter. The strongest connection to Come Away With Me might be a sense of airiness, a “less is more” approach. Just don’t try to tell Jones it sounds like a back-to-basics move.

“It’s not back to basics for me,” she insists. “I’m stretching myself to play piano under Wayne Shorter. That was pretty awesome and something I could have never done at twenty-two. And even if I could’ve, I wouldn’t have had the balls to do it anyway. So ‘back to basics’ seems like a little bit of a press release term, doesn’t it?”

People rarely stop Norah Jones on the streets of New York City for a selfie. “Medium” is how she describes her level of stardom these days. Occasionally, though, a stranger will turn to her for feedback. Recently Jones met a twelve-year-old girl at a wedding. “She didn’t know who I was, but someone apparently told her I was a famous singer,” Jones says. When the girl approached and asked for her opinion, it was simply whether Jones thought she’d be better served auditioning for American Idol or The Voice.

“As if I was supposed to pick one,” Jones says. “I said, ‘Okay, first of all, why don’t you enjoy being a kid and work on music for fun? And then, if you decide you want to do this, figure out if it’s because you want to be famous or if it’s because you love it and want to get really good at it.’ I got all granny on her. But it’s good advice, right?”

Jones makes walking that walk—valuing art over commerce, creativity over celebrity—look effortless. She’s not active on Facebook or Twitter. She hasn’t coached a television singing contest. And she’s intensely private when it comes to family; she has two young children, one reportedly born this summer, whom we know next to nothing about. Selling baby pictures to People isn’t the kind of thing that tempts Norah Jones. Maybe she doesn’t fixate on stardom the way other people do because stardom was never part of the plan. Day Breaks, seen in that light, isn’t so much a return to her first album as it is to the ambitions she entertained before she became a star.

“Let’s start in Grapevine,” Jones counters when I suggest we talk about her life as a jazz student at the University of North Texas. In grade school, Jones says she was a reluctant music student and quit classical piano classes because she didn’t like to practice scales. But in seventh grade, when she showed renewed interest in music, her mother took her to a big-band jazz concert at UNT. “It blew my mind wide-open,” says Jones, who quickly signed up for piano lessons with a teacher who emphasized reading chord changes instead of notes. “I saw that you could be free and improvisational, which is what I couldn’t do with classical music.”

During her high school years at Booker T. Washington, Jones played regularly at a local coffee shop. Her set was mostly instrumental jazz standards, but an occasional vocal turn, usually on Billie Holiday’s “I’ll Be Seeing You,” often proved to be the big tip-earner. “That’s when I realized that even if I was in school for piano, people liked it when I sang more than when I just played.” It was an awkward realization for someone who worshipped the great pianist Bill Evans. “I was a little bit of a jazz snob,” Jones says. “I wasn’t a songwriter. For me, playing jazz meant playing Gershwin and Harold Arlen songs, working on taking a solo between singing the melodies.”

The summer after her freshman year at UNT, Jones sublet an apartment in New York and immersed herself in the city’s jazz scene. She did the same the following summer and decided to stay; she’d front-loaded her UNT schedule with jazz piano classes, and had she gone back it would’ve meant two years of academics and classical musical seminars. “Honestly, I couldn’t face it,” she says. But though she came to New York to sing standards, she was becoming more and more interested in songwriting, inspired by both the Lower East Side’s burgeoning singer-songwriter scene and a stack of Townes Van Zandt albums some friends had turned her on to. By the time Blue Note came knocking, Jones was working with the band that created the jazz-pop-folk sound that launched a million radio plays.

“We had a cool vibe together from the start,” Jones says. “It never felt like we were searching for a sound. We just sort of fell together and it became what it was.”

Obviously, what it was wasn’t the jazz she had come to New York to make. It was something much bigger. Come Away With Me was released in early 2002, and commercially it was, like many of Jones’s songs, something of a slow burn. The album debuted inauspiciously at number 139 on the Billboard charts and took six months to sell a million copies. Then it sold another three million over the next six months—and finally hit number 1 nearly a year after its release. At one point, the album was such a phenomenon that Jones reportedly asked Lundvall if it could be pulled from the shelves; she was terrified of what overexposure might do to her music.

“I had all the success in the world and I wasn’t completely happy,” she says. “I was overwhelmed by it all, especially the celebrity part. That’s when you ask, ‘How do I keep this fun?’ I wasn’t sure, but I knew what wouldn’t be fun: doing the same thing over and over. How can you find emotion in that, let alone fun? So I didn’t.”

That attitude gave us the Norah Jones who these days is only sort of a star—her sweet spot, the Norah Jones we were supposed to know all along. And that’s the Norah Jones you can hear on Day Breaks.

Jones wants to tell one more story. It’s about her first car. And it starts at an unlikely place—the La Madeleine: Country French Cafe on Dallas’s Lemmon Avenue.

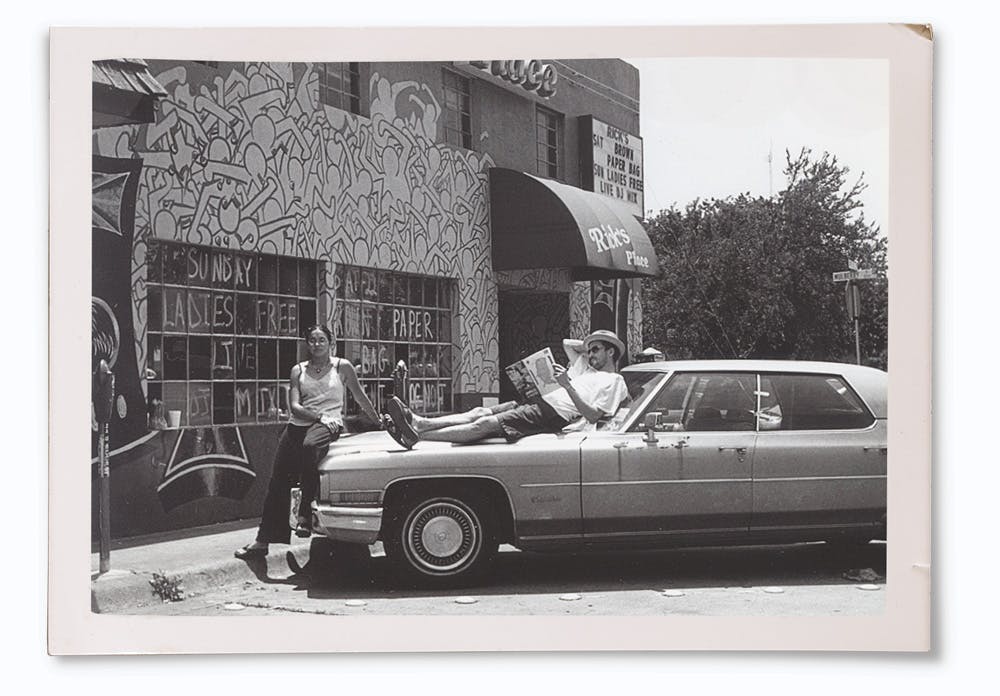

“I worked there in high school to save up money for a car,” Jones says. “My mom was nervous about me driving on busy Texas highways, so she wanted me to have the biggest, baddest boat she could find. So we bought a 1971 Cadillac DeVille.”

Jones took the car with her to Denton. During her freshman year, another student asked if she could drive to a nearby hotel and pick up bassist Marc Johnson’s band. Johnson, a UNT graduate who’d played with Stan Getz and Bill Evans, was in town to conduct a clinic at the school. “I was dorky, agreeable, and had a car big enough for the guys and their gear,” she says. Three members of Johnson’s band—Steve Cardenas, Kenny Wollesen, and Kurt Rosenwinkel—hopped into Jones’s Cadillac that afternoon. Following behind in a rental car were a couple of old friends of Wollesen’s who were passing through Texas and wanted to hang out with their buddy: a pair of New Yorkers named Jesse Harris and Richard Julian.

“I couldn’t believe I was hanging out with a couple of real New York musicians,” Jones says of Harris and Julian. “And when I asked them exactly what they did, they said they were songwriters. At that point, I honestly didn’t know that was a thing you could identify yourself as. I showed them around town, and we all ended up hanging out at a golf course over by the Radisson, playing guitar and singing songs. When I told my mom, she said, ‘You went to a golf course with a bunch of men in the middle of the night? Are you crazy?’ Whoops. Sorry, didn’t think about that. They were nerdy musicians. I didn’t ever feel unsafe.”

Jones and Harris stayed in touch; every so often, he’d send her a song he had written that she could sing at her coffee house and restaurant gigs in Dallas and Denton. And once she got to New York, it was Harris who showed her around the scene. And, yes, it was Harris who wrote “Don’t Know Why,” the song that won Song of the Year and Record of the Year at the 2003 Grammys. And Julian? He wound up co-leading Jones’s country side project, the Little Willies. The Cadillac did okay too. It was sold twice. When Jones committed to staying in NYC, Wollesen, who had fallen for the car during that visit to UNT, bought it from her. And then, a few years later, he sold it to another musician friend, Tony Scherr.

“Tony did a gig up the street from my apartment, and for four years I’d see the car once a week,” says Jones. “It made me homesick for Texas. But it’s also a giant Cadillac. There is no worse car in the world to have to park in New York City.”

The Cadillac anecdote might just be a random story about one of life’s random turns that Jones tells because she finds it amusing. But she might also tell it for another reason. Unlike Jones, most pop stars are always happy to boast about how hard they worked to get where they are, how they always dreamed of fame, and how they deserve everything they’ve gotten. Jones has worked hard too—you don’t get to be a first-rate singer, pianist, and songwriter without putting some effort in. But she worked hard at being a musician, not at being a celebrity. The celebrity, she’s at pains to make clear, was something that just sort of happened to her—her mom happened to buy her a really big car, driving a big car happened to lead to her meeting the people who helped her get her big break by opening her eyes to something more commercial than singing jazz standards, and that’s how we wound up with Norah Jones the Grammy Award–winning, multiplatinum artist.

If that car had never turned up in her driveway, she might have ended up with the career she had always imagined for herself: playing jazz in small cafes, figuring that the biggest thing that might ever happen to her would be to record an album for the most prestigious jazz label in the world, backed by jazz titans like Wayne Shorter and Dr. Lonnie Smith—and be thrilled if it sold 20,000 copies. But thanks to that Cadillac, Day Breaks will probably sell more than 200,000 copies.

And if it doesn’t? If the big news that Norah Jones has returned to the piano and to her roots results in a blip, not a bang? She’ll just make another record. And another after that.

That doesn’t mean she has no ambitions. “I’m not completely blind to expectations,” Jones says. “But I try to set the bar low for myself so I don’t get disappointed. I feel pretty good about what I do. I’m not scared about what people think like I was back when I was twenty-two. But music is music. Some people love certain things. Some people hate that same thing. What are you gonna do?”

*Correction: An earlier version of this story misidentified Dr. Lonnie Smith as Lonnie Liston Smith. We regret the error.

- More About:

- Music

- Norah Jones