Jim Pirtle would once claim that it was the center of Houston. The address of the venue and performance space—314 Main Street—was his evidence: 314 backwards spelled “PIE,” he’d say, and pi, the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter, was 3.14. Pirtle would take people up to the roof and show them the downtown Houston surroundings that encircled the 1893 building: expensive lofts, the Alley Theatre, Jones Hall, and Minute Maid Park. It was a sign, he said. From this magical spot, all of Houston radiated outward; the location would offer a shelter for ideas and strange happenings. Pirtle felt the most appropriate name for such a place would be Houston spelled backwards: notsuoH.

Before 1996, when Pirtle bought the Main Street building with his wife at the time, Missy Bosch, he was working as a kindergarten and pre-K teacher, though he had already been active in the art world. He was a performance artist known as the Polyester King of Houston (because he wore polyester from 1986 to 1992). Afterward, for a few years, he was known as the man whose goat grazed on his roof in the Sixth Ward neighborhood. Like other local artists who’d watched the Lawndale Art Center develop in a 100,000-square-foot warehouse at the University of Houston, Pirtle felt that artists could succeed if they simply bought an abandoned building and followed the saying “don’t ask permission, just do.” So when Pirtle fell off a ladder in the mid-nineties and broke his back, he began wondering, during his convalescence, if he should pull out his teacher retirement savings and buy a large space to make art. Further motivating him, the cafe where he regularly played chess with artist Michael Galbreth began discouraging lingering, as the business needed to make room for more customers. Disgruntled, he came up with an idea.

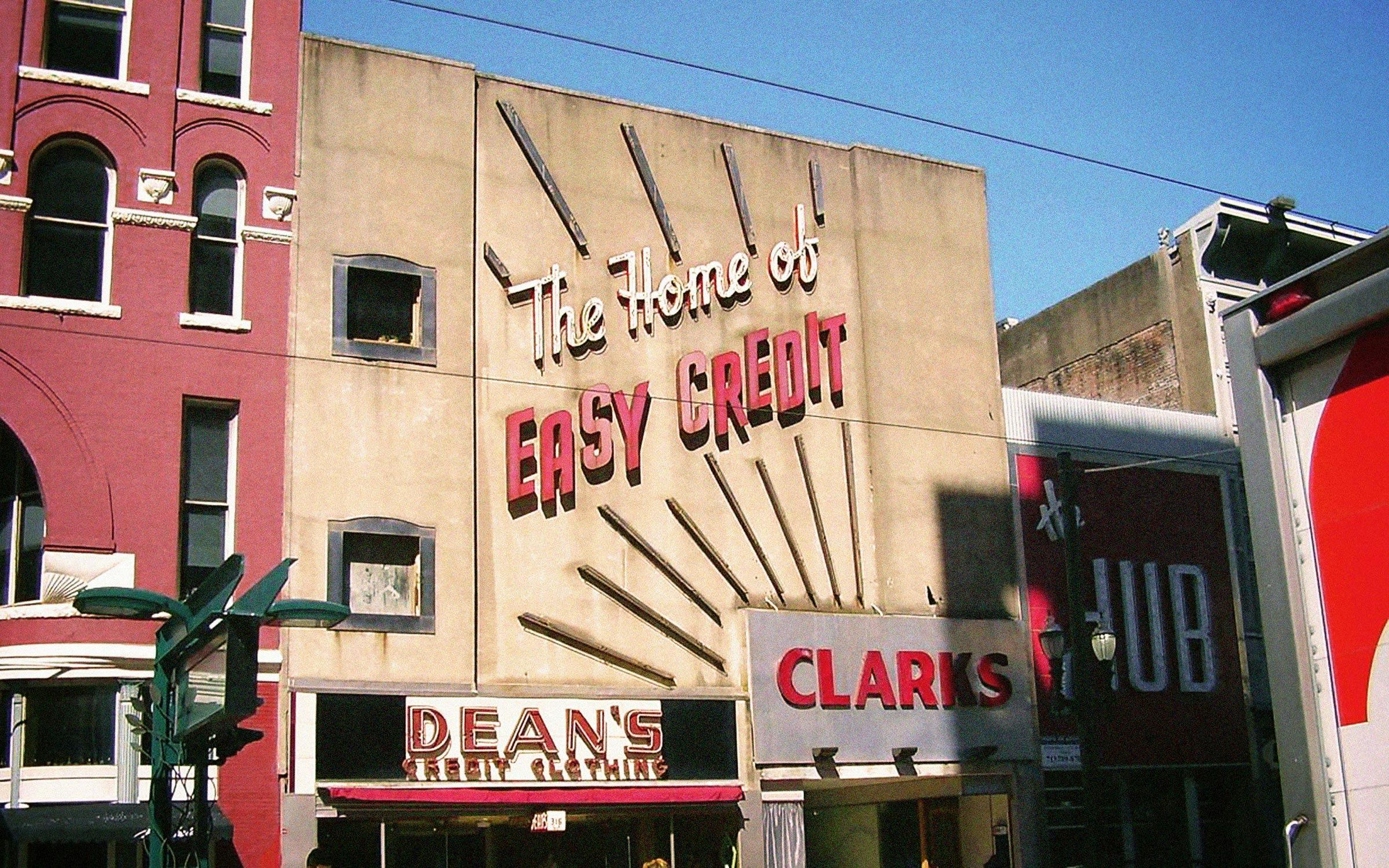

Over the past twenty-four years, the cavernous, three-story building—still bearing words from its forties facade, “The Home of Easy Credit”—has become a legendary hangout for artists, mainly, but also business types and people experiencing homelessness, who sometimes play chess side by side. NotsuoH has hosted performance art, poetry readings, concerts, plays, musicals, and occasional uncategorizable events (e.g. a make-out night), and curious patrons who wandered in never knew what decor they’d encounter. They might find a room full of plastic jungle plants, a giant blow-up pool, an exhibit of paintings, or a series of fountains. “The place is a kind of touchstone for a lot of people,” artist David LeJeune says. “At its heart it’s an art place. A work of living art.”

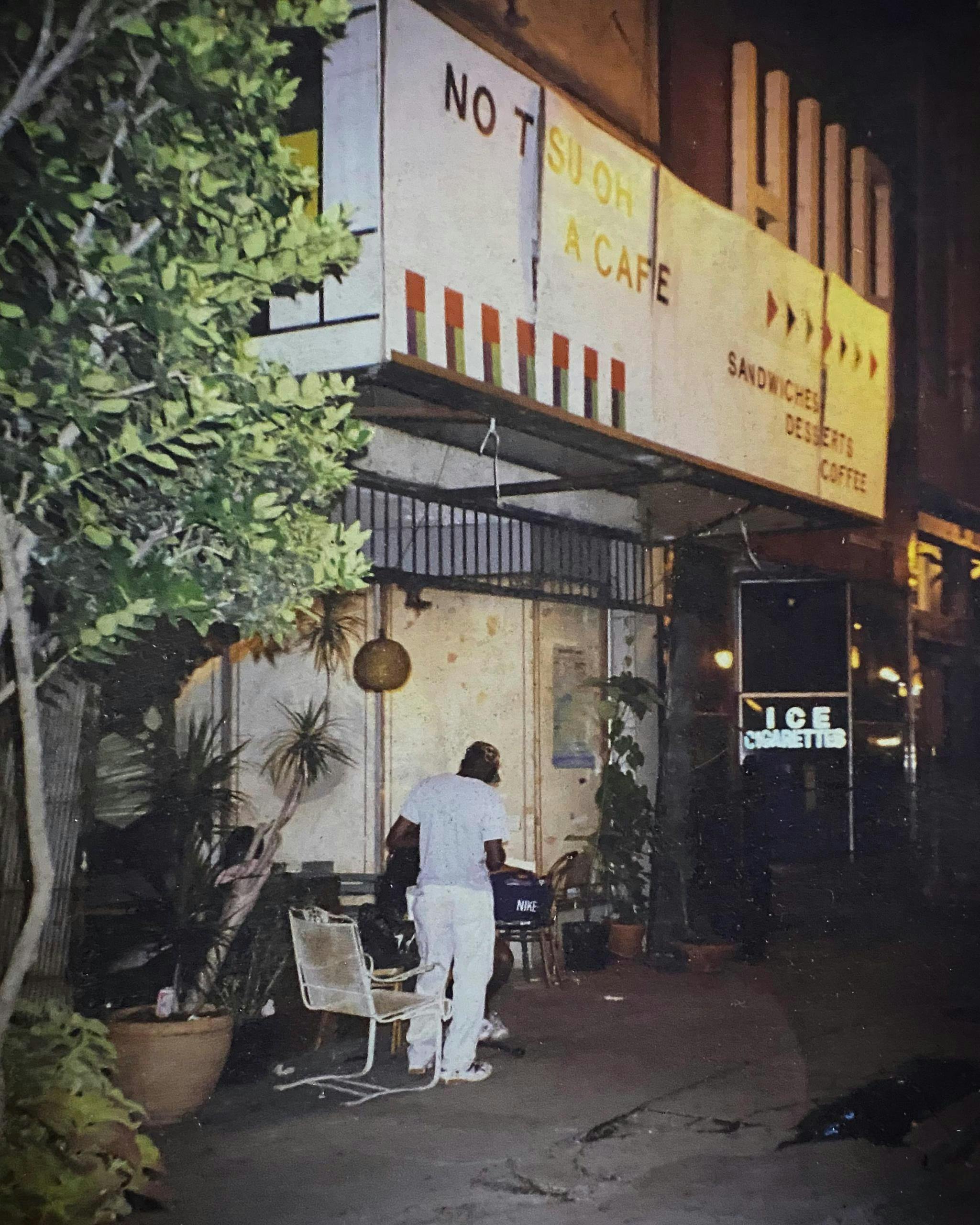

Travelers may find bohemian gathering spots in cities across the world, but those hubs are often transient; rarely do they last for decades. From its inception in the mid-1990s, notsuoH has evolved through three main eras: first, as a coffeehouse from 1996 to 2003; second, as a secret party spot from 2003 to 2007; and finally, as a legitimate bar from 2007 to present. After closing in March for the COVID-19 quarantine, it reopened on September 19, temporarily as a retail store selling clothes and antiques.

Each of these intervals bears a distinct personality, yet they all are quintessentially notsuoH. In this oral history with longtime owners, bartenders, and friends, we walk past the glass front door and enter the portal to underground Houston. Welcome.

Why Buy an Old Building?

JIM PIRTLE is an artist who owns notsuoH: Well, I wanted to open up a coffee shop. So you need to have a building. And I wanna play chess. There’s gotta be tables and coffee.

MISSY BOSCH is an artist who co-owns notsuoH: We were like, “Let’s look at old buildings!” Everything was boarded up and run-down back then. There were “For Sale” signs on the buildings and I was like, “This can’t cost more than a house.” This is before the internet. The first one we called was $80,000. It backed up to the Rice Hotel. So we called about that one building and it didn’t work out, but then one owner we talked to was like, “There’s a building down the street; they haven’t paid the taxes in years.” We tracked down the owner, got some money from Jim’s parents, and Jim cashed out retirement from his school. We bought 314 Main for $20,000 plus back taxes.

DYLAN FRANCIS is an artist: Downtown, at the time, was kind of a ghost town. When people were done working, they went back to the suburbs. There was nothing going on.

JIM PIRTLE: There’d been a porno house nearby, and they couldn’t make it in the world of VCRs.

NESTOR TOPCHY is an artist: It was like a neutron bomb went off downtown. You could lay on Main Street and few cars would come along. It was a perfect thing. We broke into 314 Main and checked it out. It had been a pawnshop and a bunch of different things. We did a video where we put on these disco shoes and videotaped our feet and looked like burglars going in—cartoon burglars looking over our shoulders.

JIM PIRTLE: This place was locked, and the pawnshop dealer told me how to break in. And so when I first got the building, I go up to the second floor, there were ten thousand pairs of shoes in boxes—brand new—from 1971. You see, before it was a pawnshop, the building was occupied by Sakowitz [a department-store chain]. And then from the pawnshop days, there was all this random stuff like trombones, guitar cases, mannequins, Christmas decorations, typewriters, gift-bow makers. There were like fifty guns, but they were broken guns, old guns, that didn’t work. He would buy stuff to resell. But like, why would you buy someone’s defibrillator?

MISSY BOSCH: To get to the third floor, climb up this ladder. And there was this huge space that hadn’t changed in one hundred years.

DYLAN FRANCIS: Each level is probably about fifteen feet high. It was a big, wide-open space. Columns go through the building.

RACHEL ROGERS is a poet and an artist: Jim and Missy own the whole building, though it has two storefronts. On the first floor, one half is the old Clarks store; the other side is called Dean’s.

CAMERON ARMSTRONG is an architect: We went down there in the late afternoon or early evening and traipsed around and answered Jim’s questions: Could we install stairs here? Would this be up to building code? How could Jim best interact or engage with the city authorities? Archeology in Houston is interesting. The city is pretty new, and most buildings are made of contemporary materials, so this was a time capsule. Usually facilities like that rot away. But this was a sturdy, brick building, and that’s what I told Jim: This building is like a bomb shelter, and there weren’t many ways you could damage it.

STEPHEN FOX is an architectural historian and lecturer at the Rice University School of Architecture: The building on the corner was the original 1893 five-story Kiam building, and Jim’s building was part of that complex. The contents of the store remained there: boxed shoes on display. You felt like you walked into the back storeroom of a 1940s downtown store.

JOHN PIRTLE is an economist, an artist, and Jim’s father: My mother worked there! I think it was Sakowitz she worked for, in 1920, right in there.

JIM PIRTLE: I was like fuck it, I’m just starting. Houston is DIY. Houston is just incredible for “just do it.” I had a license to sell jewelry. I “sold chessboards.” And Michael Galbreth and I would sit at a table here to play chess. And I had a coffeepot.

MISSY BOSCH: I was young. I was only twenty-four, twenty-five. I had a romantic notion: live upstairs and work downstairs. Shortest commute ever! My brother is a contractor, so he did the coffee shop. He started building us a house on the third floor and built a staircase.

DYLAN FRANCIS: I was one of the only people that showed up to help Jim clean a bit, so he offered me a studio there. I would paint the ceilings and help get the coffee shop ready. I don’t know how long that took. Might have taken six months or so. You could barely walk through because there were so many shelves of shoes, which we kept intact. But there were also lime-green mushrooms coming out of the wood of the beams. I pulled down the beams and a mountain of dust and debris came falling down. I couldn’t see, so I ran downstairs, and we went back up after it all settled and found an old advertisement: two suits for nine dollars! Baseball tickets for the Houston Buffalos that got swept up in the walls there. There was a lot of stuff to clean up. But it all had to be approved by Jim—any old signs, he made a collection and hung them in the coffee shop. He kept a lot of it.

JIM PIRTLE: We broke open a safe upstairs, and inside were all these old ledger books for people who shopped around the thirties and forties—old accounts that people had. Remember, this was “The Home of Easy Credit.”

DYLAN FRANCIS: Jim would have you pick a name from a ledger, and you’d get a name. Like mine was Erwin Moses. And then you’d have a card with that name on it. It was like that. So if you wanted to come in: “Let me see your membership card.”

CAMERON ARMSTRONG: We obtained membership cards on the spot in notsuoH. Old retail cards. You know when people had layaway plans? These were like layaway cards showing Christmas presents or whatever. It looked like a library card but showed how much was paid per month.

DALE LEITER is a clinical psychologist: I was Mary Smith.

JIM PIRTLE: Everybody here was Mary Ryan or Charlie Jones or something.

The Coffeehouse Era

DALE LEITER: To tell you the truth, I have no idea how long the membership-card period lasted. At some point, it just segued into something more. Other people came rather than just the small group.

DYLAN FRANCIS: We started doing the coffee shop thing. Initially, it was open from noon till six in the morning. Jim himself was a collector, so the coffee shop was decorated with couches and lamps. He had multiple pianos. Once he got the coffee shop going, Jim invited people up for parties on the second floor, but there was no heating, so cold, raw air would come in.

JIM PIRTLE: Then I lost the keys, so I said, “Fuck it. We’re just open all the time.”

MISSY BOSCH: We started staying open twenty-four hours because Jim was pretty much always here. We did coffee and lunch for daytime people. It got busy during the day because of the courthouse building nearby. We got a lot of college students. It attracted a lot of bartenders and stuff after they got off work. Service industry. Young adults. People who could stay up all night. Artists.

JIM PIRTLE: It had this artsy bus station feel. There are art bars. Oh, they have art, so it’s an art bar. Or they serve drinks, so it’s a bar. Not here. This is an art bar because the bar itself is a piece of art. The place is a work, a social sculpture.

DAVID LEJEUNE is an artist: I started hanging out there a lot and loved these people, and after a while Jim asked me if I wanted to work there. And it was like, “Okay! Yeah, that’s exactly what I was hoping for!” I worked there Fridays from six to midnight, which was perfect. I’d make sandwiches and cappuccinos or lattes. And tea. Pretty simple. Sometimes, you’d see someone nicely dressed playing chess with a homeless person. There was no age limit, and all these wonderful people would present themselves to me. And then I’d wander upstairs after my shift got off.

JIM PIRTLE: People were living here; that’s how I paid them. You get to live here, but you’ve gotta work your coffee shop hours. On the second floor, there was a tent city.

DALE LEITER: One night, Jim turned to me and said, “You want a job?” I started laughing. I was working as a psychologist during the day. I said “Sure,” having absolutely no idea what I’d gotten myself into. Seven years of grad school didn’t equip me for making sandwiches. I couldn’t make commercial espresso. I immediately fell in love with the idea of being in the service industry because it was so different from my typical life. It’s very different looking at the world on the other side of the counter. I’m fascinated—I’m a voyeur. People are my thing.

HENRY SANCHEZ is an artist: Michael Galbreth [half of the artistic duo the Art Guys; he died in October 2019] played chess with Jim every week.

JIM PIRTLE: Michael was a conceptual artist, so our way of discussing conceptual art was building up ideas. As he got better, I would get better, and as I got better, he would get better. We kept countering each other with stronger arguments, stronger ideas. It became not about winning. It became about how that argument shifts.

DYLAN FRANCIS: People would be hanging out on the patio playing guitar and someone else would be doing a live painting, somebody else would be running around naked. There was a live nude drawing class on the second floor. From one day to the next there was never a dull moment.

BILLIE DUNCAN is a poet: Jim is a one-man booster club, and notsuoH became a reflected hub of underground Houston. Houston is a city that says, “Yes.” When you have an idea, you can go to city government and say, “Can I do this wacko thing?” and they say, “Okay, what can we do to help you?” Jim is like that. There is no filling out forms.

JIM PIRTLE: Richie Hubscher was a ballet dancer with Houston Ballet; he ran a ballet class upstairs.

DYLAN FRANCIS: A troupe of twelve people would rehearse and would write these plays—I think the first few were based on Tom Waits music. They were like musicals. So there was always something going on. I worked the midnight-to-six shift, so I’d be trying to sleep and I’d wake up to “One, and- a two, and-a three.”

NICK COOPER is a drummer and composer known for his work with the Free Radicals: In November 1999, Free Radicals decided we wanted to play a twenty-four-hour concert for charity at notsuoH. We started playing at noon at notsuoH to not much fanfare. Around ten p.m., things were really cooking with guests coming in and taking over while we rotated out. The place was packed.

Several hours later, weird things started happening. Maybe around midnight, we heard a crash, and the right display window had fallen off and smashed on several customers sitting at cafe tables. Someone swept up the glass and the band kept going. Around four a.m., the easily annoyed and aroused poet Malcom MacDonald [who died in August 2019] was sitting with someone and decided the music was too loud for his conversation. He began a thirty-minute session of screaming “Shut up, stop playing” in each of our faces, with spit. We kept playing. Around six a.m., I realized that I was somehow playing drums while napping. I would wake up and notice I was playing and then I’d doze off again. Around nine a.m., Marcos, our sax player, had put a lamp shade on his head, a curtain around his shoulders, and a curtain rod became a lance for some jousting with windmills on the sidewalk out front. Around ten a.m., people started filing in to see our final stretch. At noon on the dot, we stopped.

CAMERON ARMSTRONG: A certain kind of person would migrate into Jim’s orbit. Like some people from the [Public News] newspaper are having a drink and bemoaning its closure and he’s like, “I’ve a got a mezzanine…”

BILLIE DUNCAN: We ran a newspaper out of the mezzanine after the Houston Press bought Houston Public News. It was called Houston’s Other. A rooster owned the building from the mezzanine up. And the rooster would come in and walk around on the desks in the newspaper office, looking at the monitors, pecking at the papers, and, occasionally, pooping on them. There’s always a critic.

JIM PIRTLE: We used to have a Pakistani restaurant upstairs. I knew a Pakistani woman who was a doctor, a pediatrician, and her sister ran a restaurant after hours, so the restaurant opened at two in the morning. People could come here and eat really wonderful Pakistani food.

DYLAN FRANCIS: Jim ran a children’s theater for awhile. We did “Shoemaker and the Elves,” “Little Red Riding Hood,” which we all participated in as characters.

JOHN PIRTLE: Once, Jim played a prank on somebody sleeping in a little area. Jim put up some Sheetrock, and in the morning—bang! bang! bang!—she said, “You’ve locked me in!”

NESTOR TOPCHY: A friend of mine was sleeping at notsuoH one night, and way up high on a wall, Jim had record players rotating and a chicken was rotating. And every now and then the chicken would shit and it would land somewhere. And my friend had to leave, he was laughing so hard. No way he could get any sleep.

DAVID LEJEUNE: One national magazine art magazine that wrote about notsuoH of that era said it was a cross between Sanford and Son and Alice in Wonderland. I thought that as very apt.

JIM PIRTLE: I always found humor in pretending that this is normal. You cannot tell that I think it’s abnormal. So a fly would fly onto my eye, walk around on my nose, and I continue to talk to you as if nothing is going on. And I’m fully aware that a fly’s crawling on my nose and is bothering you. And what bothers you most is that I’m not reacting. And that’s the essence of notsuoH. It’s this fly crawling around downtown on someone’s nose and that person doesn’t seem to react. Truth be told, it’s a comedy—but comedy is serious.

NESTOR TOPCHY: Jim likes to shock, disgust, punch their buttons as a medium. He likes to provoke people.

CAMERON ARMSTRONG: It’s a place more for artists than for collectors or people who see themselves as “art knowledgeable,” whatever that means. Some curators are about the artist and not about the art object. To the people, not the things. Jim is a curator of a community. I was friends with Walter Hopps, the founding director of the Menil Collection, and we went down here a couple of times, just to see what the heck was going on. And Hopps declared it a piece of found art with all the other things glued to it.

Raising a Family

JIM PIRTLE: My daughter, Martha, was born in ’97 and grew up here, so there is a child growing up in this. Bands would be playing, and she’d be in the bassinet. She could sleep through it.

MISSY BOSCH: There was nothing down here, so you couldn’t run and get milk or get a sandwich. So that was hard. At first, it was fun staying up all night talking to people, and then I was pregnant and had a kid and was all over the place.

MARTHA PIRTLE is an artist who is Jim Pirtle and Missy Bosch’s daughter: I grew up on the third floor. Most of my early childhood was there. I have lots of random memories—like every year since I was born until I was ten, I had my birthday there and they’d put on plays. My dad was always involved and tried to make it special. Growing up there was interesting, because everyone thought I’d end up horrible. I remember once I had a root beer in my hand, and someone thought it was a beer and threw it in the trash.

BILLIE DUNCAN: His daughter was a cute little tot. I just adored her. She’d wander through, check things out, talk to us. Between the rooster and the sweet baby girl we had a lot of warmth and life around us all the time.

DAVID LEJEUNE: One night, a bunch of us were sitting around a table and his daughter, in a princess dress or something, got up on the table and proceeded to dance from one end to the other and it was just perfect. Inventive and graceful.

MARTHA PIRTLE: I used to be very outgoing, which is not me now, but when I was little, I liked going onstage and talking to people. People would be playing chess and I’d walk over and watch, and they’d be like, “Why is this child watching me?” I never wanted to go to bed. When we had the ballet classes upstairs, I’d be crawling around and dancers would be like, “She has to leave,” and the teacher would say, “No, this is her space, you have to dance around her.”

MISSY BOSCH: I lived at notsuoH for about four years. I’m not as social as Jim. He has always been the major personality in the building. That’s why I left too: it wasn’t us doing this project, it was him. Whenever I tried to contribute, I got pushed aside. I was young. I could have pushed back more, but I didn’t.

JIM PIRTLE: My daughter moved out of the building when she was twelve years old. I was running the bar. She moved back with her mother. Her mother and I separated.

MARTHA PIRTLE: I used to stay on the mezzanine, and then it got too loud. It was easier if I stayed with my mom, so I spent most of my time with her. But my dad would come to school every day on the bus to pick me up and we’d ride the bus home together. Everyone expected me to be an artist, an eccentric. But in school, I wanted to be a mathematician. That was my rebellion!

The Fire

JIM PIRTLE: At some point there was the first rejuvenation of downtown, where suddenly it became like fine dining and nightclubs.

ANN PIRTLE is a former schoolteacher and Jim Pirtle’s mother [she died in September 2020]: It was all right for the cat to be in the front part, but the cat wasn’t supposed to be back by the kitchen. Well, once, during an inspection, the inspector walked in on the cat in the kitchen, so Jim threw a box top over the cat. The inspector finished up and the box top kept walking round and round the kitchen. The man never did know there was a cat there.

CAMERON ARMSTRONG: They had wild parties upstairs, and there are movies of those parties. Nothing naughty, but wild binge-drunk pictures of people knocking lamps over.

NESTOR TOPCHY: People who aren’t in control of themselves, when they’re at notsuoH, they’re bouncing off each other and you get volatility and weirdness. You’re already waiting for Godot and something’s going to happen. At first it was mayhem: unspeakable things, like in a Fellini film. You can’t imagine. People started stealing stuff, and Jim was permissive so as long as everyone was having a good time. But he fell asleep on the couch and the fire surrounded him. A ring of fire, like the song.

JIM PIRTLE: I woke up naked with a couch on fire. There’s people down in the coffee shop, and I grabbed a painting off the wall and wrapped it around me, then I ran out and called the fire department. So I’m out on Main Street wearing a painting. The fire department came to put out the fire. But then the city inspectors came and they were like, “Wait a minute. No, you cannot do this.”

CAMERON ARMSTRONG: If the city doesn’t catch it, the fire will. I was surprised. And not. Given the kind of things that went on down there? Shit happened. But shit can happen anywhere.

DYLAN FRANCIS: So when the fire happened, the city came in and saw that his wiring wasn’t up to code. So they had to make him shut down until he got an inspection and got it rewired.

DALE LEITER: I think if you look at it longitudinally, the fire was more symbolic than anything else. I think Jim was ready for a change. I think he needed to back off from notsuoH. And the fire kind of did that for him.

The Secret Party Era

DYLAN FRANCIS: The coffee house was no more after the fire. Jim needed some kind of income, so he rented out Dean’s [next door]. That’s a bar—and remains one to this day. For a while, he also rented out the Clarks side to the same guys. They did a lot to it. They totally renovated it: put in a cement bar with lights, wood veneer on one side of the wall. At some point a stage was built. So it went from coffee shop to kind of a dance club, a posh kind of thing, which was strange.

JOE ORTIZ is a musician: I remember walking in [after the renovation] and thinking, ‘Whoa, what the hell happened to this place?’

NESTOR TOPCHY: You had to knock to come in upstairs. There was an inner circle with Michael Galbreth and Jim’s other partners in crime. He had to keep it cool enough because you didn’t want to be discovered. Later it became really hard, with the internet and selfies and self-published bullshit. That changed it dramatically.

SAL MACIAS is a poet: It was mainly open on weekends, but sometimes on weekdays. What separated it from an ordinary party was the attendees. Intellectuals. Musicians. Artists. People in the arts scene. Chefs and waiters who would go out and unwind, the bartenders downtown. Scientists, bankers, politicians—I remember having a conversation with a city councilman there.

RACHEL ROGERS: In 2004, I fell out of a window at notsuoH after performing. I hadn’t had enough to eat but then I fell over. I don’t remember what happened. I had been going ninety to nothing and I have blood sugar issues. Basically, my entire body fell onto the concrete. I landed in a handstand. I wasn’t conscious at the time. Broke both my wrists and cracked my skull. I did survive. I’m responsible for my own actions; that’s how I see it. When I was in the hospital, Jim offered to help with my medical bills. Subsequently, he said, “I’ll give you a free bar tab for life,” and now it’s free chess for life for my daughter.

SAL MACIAS: Towards the end of that era, he did begin to become more lax in letting people come in. People who Jim didn’t really know.

DALE LEITER: It went from being a fairly creative, interesting place to just being a place to get an after-hours drink, and I pulled away from that. I didn’t find that interesting. I didn’t find people of substance. For me, notsuoH lost some of its specialness. It didn’t provide as much as it did in the first era. It was a gathering place with limited interaction among the patrons.

HENRY SANCHEZ: Some pretty nefarious people came through there. And in retrospect, it’s not that funny.

JIM PIRTLE: Then there’s the fall. And this is a hard story. And it’s all on the record. But it’s a horrible story. Late at night, I’m having a private gathering of friends. And someone who came here—I did not give him a drink, but he was at a 2.7 blood alcohol level when he got here. And he either went up to the third floor and jumped or fell out. Whether he fell or jumped, we do not know. He has no memory of it. He survived. But he is in a wheelchair for life. I got sued for twelve million dollars and forty-seven cents. Forty-seven cents on the dollar. They added it all up. I’m like can’t you just round it off? “No.” I went to court.

CAMERON ARMSTRONG: People get hurt. They really do. Jim was opening himself and his place and his life to everything that can and will happen without a whole lot of filtering except as he was required. That put him at extreme risk.

JIM PIRTLE: That changed the whole thing—whoa. I shouldn’t have to explain the safety features of a window; it’s a window. But this is real. They’re trying to take the building. And his family sued me. So every dark hole in this place—they led me into court and four days of trial and “What we are doing up there?” “You run this nut show; you are responsible.” The jury was like twelve to zero, “Not your fault.”

But it caused a lot of self-reflection. It caused a lot of: How far can you stretch the rules? Because the rules are there to preserve people’s safety? Maybe there’s a reason for the rules? Maybe you transgressed the rules and someone got hurt because of my transgression? There was a lot of moral inventory that I had to go through. And I’m not totally clear on my culpability and moral responsibilities, and I feel horrible. But that’s part of the story. I’m trying to own my shit and not lie to you. I’m trying to own it. And it’s difficult to own everything you’ve done.

The Legitimate Bar Era

CAMERON ARMSTRONG: When they were rebuilding the trolley line on Main Street, Jim put Astroturf on the sidewalk. He had beach chairs, and he’d sit out there holding a glass with an umbrella in it. Talk about an acerbic comment.

JIM PIRTLE: After the rail was finished, a new wave of downtown began and all this other shit started pouring in.

DALE LEITER: When Jim started again, it was as though notsuoH had been hibernating. People who had known about it heard about it because it became integrated into the lore of the community. People returned and Jim did what Jim always does. It was as though Jim also came out of hibernation. It was a giant diorama and he’d be moving the pieces around. He’d move the art, the furniture, he’d put up some theme. I couldn’t find anything.

RACHEL ROGERS: He was using found objects for a while and making them into water fountains. Another time, he put a pool in the bar with pool balls on it, so it was like “ha-ha, a pool party.” Some people sat at the table with their shoes off in the water.

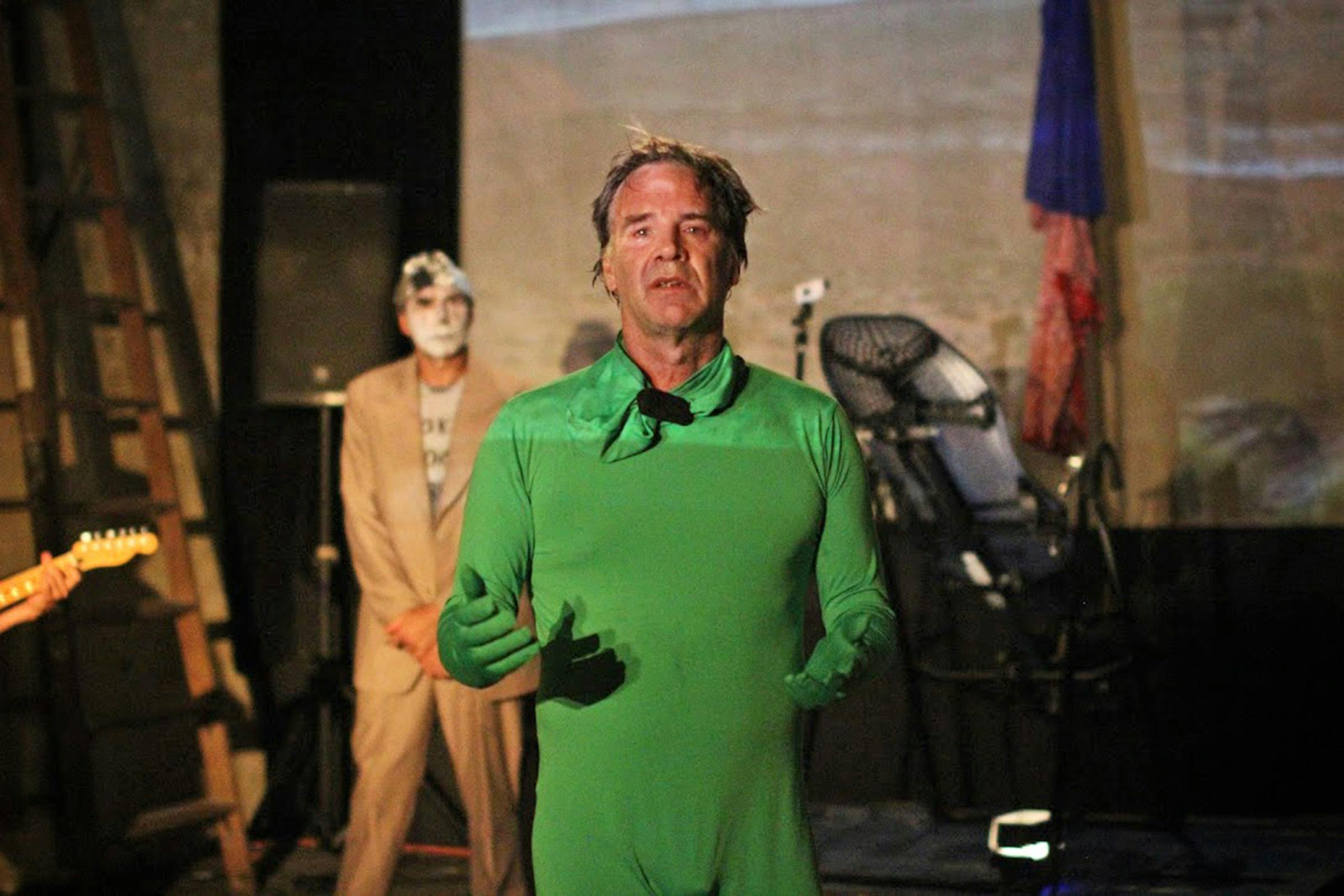

JULIA CLAIRE is an artist: notsuoH has really nurtured the performance art scene. I wanted a place where artists could perform for other artists on any level. Jim did a piece inspired by having to clear out the space, which is so hard for him. He’s attached to memories and items, so it became a cathartic experience. He had different condiments painted on his body to match the chakra system. And then, during all this, he was talking about his life and how hard it was for him to part with these things, and he danced with his father. He actually had his father be part of that piece. He had some of his dad’s paintings up. It was about family and memories.

HENRY SANCHEZ: The Art Guys did this joke marathon. They invited the public to come in and they would take turns telling jokes. But each joke they told started the exact same way. So “a guy walks into a bar” and then the rest of the joke. And it was eight hours of that.

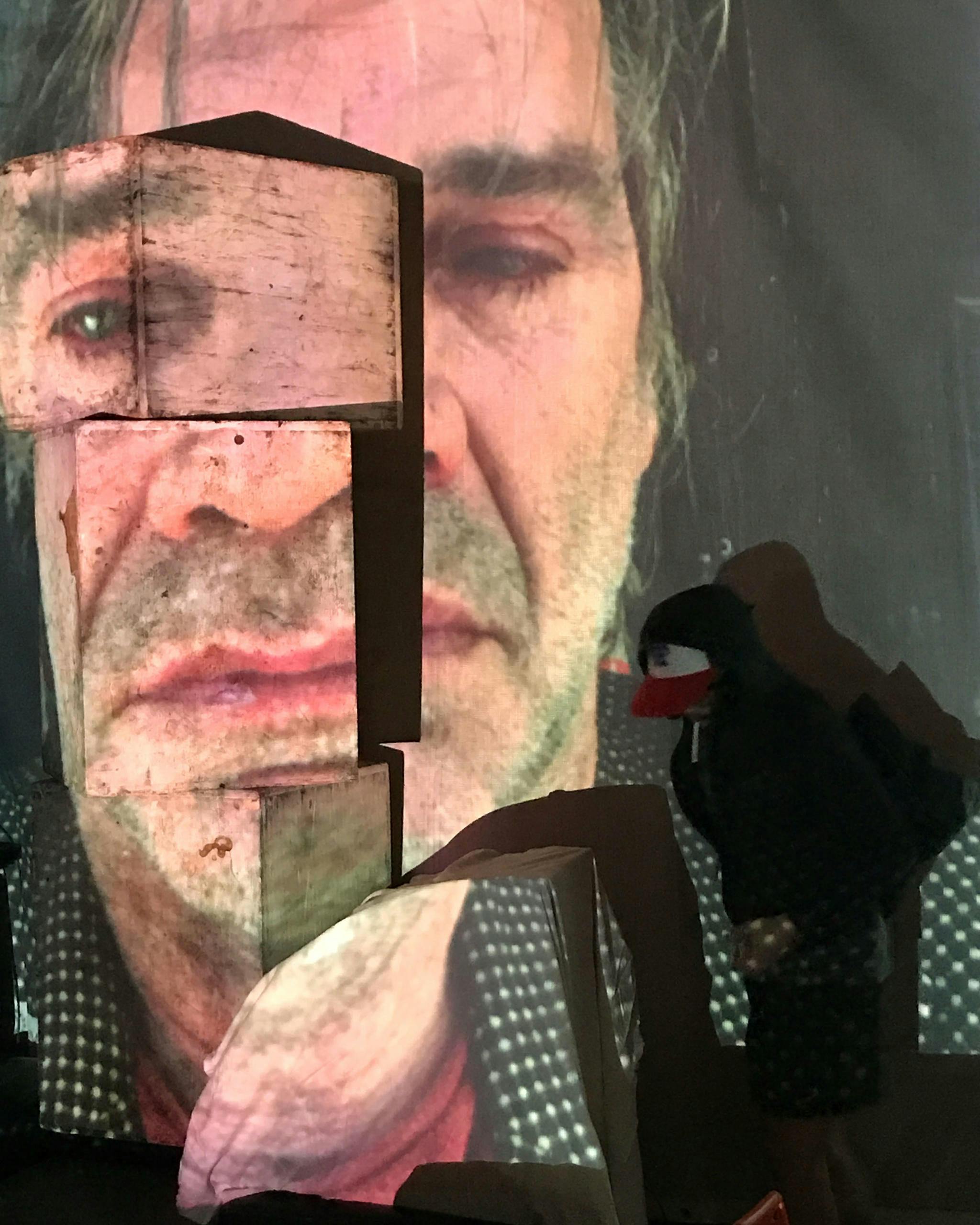

CAMERON ARMSTRONG: Nestor Topchy did a Ukrainian wrestling performance on the second floor. It seemed to me he was combining Mexican studio wrestling with Ukrainian, like, martial arts? He’d be wearing a mask with white stripes and doing these various moves.

JOSEPH UNDERWOOD is a musician: One time my band took the audience onto the train and we played on the train while it was making its stops. Another time, we had people in the audience come up and start beating up our band. My friends did an electronic music set in the girls’ bathroom.

BUCKY REA is a poet: What I liked about the poetry scene there was there was sort of a Thunderdome vibe to the place. You had to be tough enough to take it, but there was protocol. For soft-spoken performers there could be a spontaneous refrain of, “Shut the fuck up!”

SAL MACIAS: Poetry night was definitely was not for the faint at heart. He had some amazing poets come through there. I’ve had my share of fistfights in there. It doesn’t seem like something that would happen at a poetry reading. But scenes can be incestuous. Everybody’s screwing everybody, typically. That and I remember I got sucker-punched for heckling somebody. I guess I hurt his feelings. All I remember saying is, “Hey, read something different!” Some people are one-trick ponies. Sometimes I called people out on it. Once in a while people didn’t like it, but that’s okay. I got a jaw like a rock.

BUCKY REA: If there’s a recent pivot point, it’s around a number of suicides in the poetry community, 2013. Generally speaking, there was a lot of pain in the air.

BILLIE DUNCAN: There were a few suicides in a short period of time. It was terrible. They didn’t necessarily know each other. You just knew a dead wind was blowing.

JIM PIRTLE: Wonderful things happen, and so does tragedy; it’s Shakespeare. You can’t have everything great or it’s a lie. You know, I could tell you everything is great and lie to you, if you’d like. This place has a function as a place to have ritual—in the worst and in the best moments.

SHAWNA MOUSER is an artist: We were all talking about suicide: What was this? How do we react to it? How do we fix our community? We never identified what that was, but we did have some people step up and say, “I need help.” They gravitated to me and Bucky. I became the mom.

JIM PIRTLE: Around this same time, after the tragic Ghost Ship warehouse fire in Oakland, we quit having houseguests on the second floor. Before, it was friends hanging out and talking about art. And then it became something I don’t really—it felt wrong. So I stopped. I mean, you have to be intuitive and sensitive to this is not an art project anymore, this is bullshit. So since 2016 we have not had a guest upstairs drinking for the private social gatherings. I’ve got a bar, I still get to do stupid stuff. It’s not like it’s all over. It’s just limited in the exposure.

The Future

HENRY SANCHEZ: A little over a year ago, Jim and Missy were offered four or five million for the building. Jim was ready to go. He was like, “I’m tired. I’m tired of working all the time and tired of managing this.” He did a performance about it where he’s dressed in a green spandex body suit and was hung upside down and would have images of traveling across the country. But he was saying, “Things don’t last; this might be my last performance here.” Everyone was getting concerned. I thought, “He’s going to sell it.” Then sure enough he says, “no,” and now he’s building art studios upstairs so it’s going to be even more active. It’s like: he’s not going to give it up. No way. What’s he going to do with the money? Where’s he going to go? He would give up his purpose in life.

JULIA CLAIRE: I’ve been there when people say, “You should sell this,” and he makes this noise. Or people say, “This is what you should do with this space! I should manage this bar!” Some guy last Sunday was like, “He should let me do this; he could make so much money.” But Jim doesn’t take any of the ideas that could be profitable.

SHAWNA MOUSER: Off and on, over the years, he likes to tell people he’s selling it just to get people talking. I think it’s fun for him.

MISSY BOSCH: We’ve had it on the market for a long time, but we don’t have any offers. We’re not actively knocking on doors, but it is listed. It has been listed for a while, like maybe five or ten years. We go up and down on the price. Our daughter doesn’t want us to sell it. She wants it to be her future. I say, “If we get four million, that’s a future for you.” My daughter used to say, “I don’t want anything to do with that building,” and now she says, “I want that to be my future.” It’s hard to say what will happen. She’s twenty-two.

MARTHA PIRTLE: Kind of immediately after I started working there, in 2015, I started taking a bigger role. The bar was unorganized, and people didn’t want to follow the rules. I like things to be fair and for actions to have consequences, and my dad doesn’t like that, but I thought the place could be improved with a little structure. Like I made a handbook of how you’re supposed to open and close the bar. Some people gave away drinks and I said no, you have to charge, because you don’t want to get into trouble. Keeping order to some extent. Not getting rid of the chaos and how it looks, but keeping employees on the same page. Some people didn’t want that. They didn’t want change.

SHAWNA MOUSER: The bar is so organized now. Sometimes Jim comes in and is like, “This isn’t notsuoH!” We all laugh.

JIM PIRTLE: This place operated heavily in the gray and so now my daughter—she dealt with her childhood by going, “Enough gray, I need parameters of rules for orientation.” And she’s smart enough to figure out her own sense of rules. And so here she’s a lot more dictatorial than I am about right and wrong.

MISSY BOSCH: My studio is now on the second floor of notsuoH. I love it here. I used to cringe when I came here—typical bartender stuff—but I love it here now. Sometimes I can go home, but don’t want to. I’ve come full circle being in this space. Before, when it was sort of the beatnik art scene, it was people with no jobs, and now it’s more of a mix of people. The people downtown changed in general. That would be my perception. We still have some regulars but other people, too.

JIM PIRTLE: Now, instead of fifty people staying up at all hours of night, hanging out, now it’s going to be like six artists doing individual projects. We’ll have more impact with individual artists rather than the party as a piece. I’m kinda too old for that. It’s going to be private property and it’s just like six people are using it. Jim’s Easy Credit Storage Units. That’s what I’m coded for, storage units. Storage of an artistic nature.

RACHEL ROGERS: It’s a living canvas of Jim’s brain. It has always been that.

JOHN PIRTLE: Ann and I go down there when there’s a woman we know, a psychiatrist [Dale Leiter] who tends bar. On Monday nights she has an entourage, so Ann and I go down and sit down out front and have a glass of wine and talk to Jim. Get to know everybody that wanders through.

ANN PIRTLE: It has been a fascinating experience for us. I didn’t have a glass of wine till I was thirty years old, but I discovered that sitting in front of the building and watching Houston go by is a very interesting, pleasant thing to do.

HENRY SANCHEZ: People think about an art scene and sometimes they think about paintings on a white wall in a clean space. Jim—as well as a bunch of other artists in Houston—didn’t want to adhere to that paradigm, that way of working. This is what Jim wanted to do: create his own world.

JULIA CLAIRE: There are people who can appreciate things not working like they do in other parts of the world—people who appreciate the strange or the quirky, or they just can’t follow the rules or don’t want to follow the rules. There are different rules in notsuoH than in the rest of the world.

Correction 10/06: A previous version of this article stated that the building where notsuoH is housed dates back to 1902. This article has been amended to reflect that it was part of the Kiam building, which dates back to 1893.