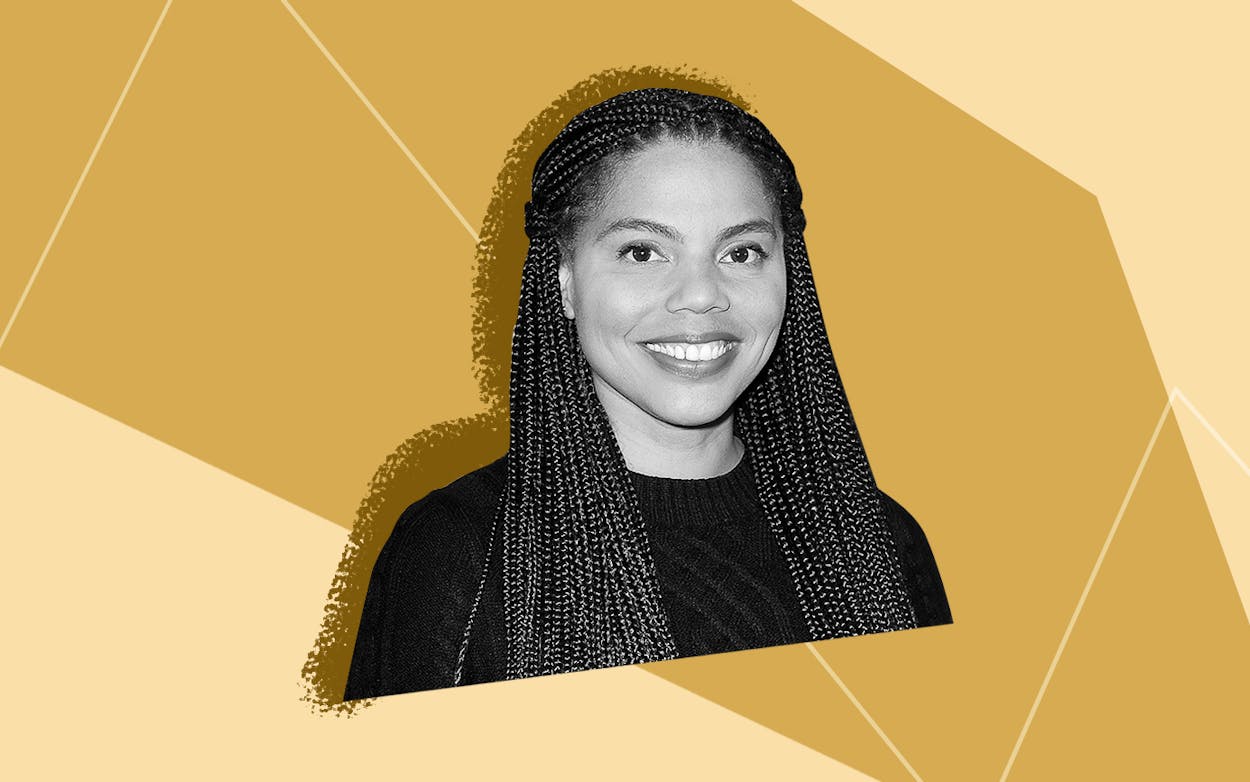

When Channing Godfrey Peoples searches for inspiration, she never has to go very far. Peoples still lives in Fort Worth’s historic Southside neighborhood, where she was born and raised; her work is inspired by the community of Black folks that nurtured her. And wow, has that worked out. Since the release of her first feature film, Miss Juneteenth, last summer, Peoples’s star has continued to rise. It would take too long to list all the nominations and awards the writer and director has accumulated since then, including the Louis Black “Lone Star” Award at South by Southwest and a handful of Film Independent Spirit Award nominations. All in all, Miss Juneteenth has won or been shortlisted for more than thirty accolades.

Still in the midst of doing press for Miss Juneteenth, which is streaming on Amazon Prime, Peoples is back with Doretha’s Blues, a short film that debuted at SXSW this week. At just under fifteen minutes, the emotional, harrowing story follows a singer whose night at her local watering hole brings back memories of her son’s death decades before.

It should come as no surprise that Peoples recently signed a deal with NBCUniversal production company UCP. She’ll be writing, producing, and directing for television, including an adaptation of Miss Juneteenth. Peoples spoke with Texas Monthly about her new short film, her creative process, and the community she holds closest to her.

On the praise for Miss Juneteenth

I was really happy to see it go out in the world and connect with people in the way that it has. It was definitely a passion project that I wrote around the community in which I grew up and, you know, inspired by the women in my life. I was chronicling some of my own experiences, and definitely those of my mom.

I watched her juggle her dreams and raise children at the same time. And it just inspired me in so many ways. And also, Juneteenth was just so much a part of my life that it felt natural to be able to create a narrative that really spoke to what Juneteenth meant to me, and especially Miss Juneteenth [the pageant]. So it’s wonderful to see it connect. I really was making the film from my heart and I just wanted to see the film done and out in the world. Everything that’s happened since has just really been icing on the cake and a gift.

On Doretha’s Blues

Doretha’s Blues is another project coming from my heart. It is about a blues singer who, decades ago, lost her son and it really robbed her of her will to sing. There’s a painful news story that comes out that interrupts her nightly visit to her local dive bar, and the memories of this event that she suffered really come flooding back.

It was a project that I conceived after I had seen the events that happened in Ferguson at the killing of Michael Brown. I always had this question: What happens to the people who get left behind? And so Doretha’s Blues kind of came pouring out of me after I asked that question.

On the difference between making a short film and a feature-length movie

In both instances, it’s telling a story that has a beginning, middle, and end. In the case of Doretha’s Blues, there’s so much that I feel like this film is navigating in terms of the lead character’s emotional state. So you have to be really there with her emotionally. The short depicts Doretha being able to take a step forward in her journey. We’re not chronicling everything that happens afterwards.

On working with Tonea Stewart, who plays Doretha in Doretha’s Blues

It was everything I dreamed of and beyond, because she’s someone who can bring such nuance and context to every world when she throws herself into it. Part of why I was able to be very succinct and economic with the story was her being able to bring Doretha to life in the way that she did. When you see the film there are moments where she’s just sitting there and contemplating, and you’re with her every moment because she just embodies it.

On where she finds inspiration these days

I’m someone that is very inspired and informed by the world. And, you know, even in conceiving of and writing Miss Juneteenth, I was often, like, out in the world for research—at the parade volunteering with the Juneteenth committee, I would go and sit in the bar and just soak up the life in there. It is an adjustment to not be able to be in the world and not be able to be with people.

But I’m also a creative that needs time to just be quiet and let stories flow through me. And so I’m really starting to take that time to do that, because we’ve been in press for Miss Juneteenth for quite a while and all these incredible things have happened. I don’t know that I have given myself permission to fully sit down and commit creatively, but I’m absolutely doing that now.

I also have my little inspiration in my toddler, who keeps me on my toes. I just took her outside to have some sunshine. Just watching her discover new things, like a new flower or a bird or things like that, I remember to embrace that sense of simplicity and to just really let creativity flow in a simple way.

On her creative process during the pandemic

Miss Juneteenth was my first feature, but I still have a well of ideas. I’ve been gestating ideas, like, my entire life since I got interested in storytelling. Time indoors has been an opportunity to really refocus and say, “How do I see these stories now? How do I frame these stories now?”

But I am looking forward to getting back in the world. This has been such a difficult time for all of us. It wasn’t just the pandemic, but it was also the things that we were navigating in the Black community, and still navigating. I just want to get back into the world and be able to connect with folks.

On how Fort Worth shaped her

I grew up in Black Texas in Black Fort Worth. What I saw were people who are determined and there was a grit about them. But they were also graceful and they had a sense of pomp and circumstance. They celebrated every day. So I think that definitely shows up in my work.

One of the things that I love about the community in which I grew up is that on the surface, you see people are working every day and then living for the weekend. But if you look deeper, they’ve created this ecosystem that, at one time, was supported by Black business and Black commerce, especially on the Southside. And they’ve maintained it and they hold on to their own businesses and legacy businesses that are passed down through generations. It looks simple on the surface, but there’s this complexity in the way people live their lives. I think my work has the same kind of approach. It tells a story in a matter of fact kind of way, but you have to think about it and start pulling back the layers to realize that there are other things underneath.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Fort Worth