This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

SNOOP SCOOP: When longtime Houston Post gossip columnist Marge Crumbaker decided to call it quits after a quarter century of professional eavesdropping, Post head honcho David Burgin wasn’t even sure she needed to be replaced. After all, hard-boiled news vet Burgin was trying to give Post owner Dean Singleton’s acquisition an upscale, big-city look, and he didn’t see a daily catalog of the city’s no-longer-so-rich-and-never-very-famous as part of the make-over plan . . . It seems Burgin changed his mind after Houston society gal and literary aspirant Carolyn Farb volunteered herself for the job. Just the rumor that Farb would be Houston’s new plutographer plunged the populace into gossipteria, and soon everybody who was anybody in Bayoutown social circles had put in for the job. (We know you local silk-stocking types are a bit strapped, but puleeease. Journalism?!?) . . . But the wily Burgin was only stringing Farb along for the publicity, and when it came time to hire, he jilted her for longtime local PR gal Betsy Parish (FYI: Betsy’s a kissing cousin of Secretary of State James Baker). Farb made a graceful exit, but Parish’s entrance last December ran into a snag when she flunked the Post‘s physical (that’s right, even scribes must meet certain minimum standards) and ended up on Fondren Twelve at Methodist Hospital, where the medics told her to dry out or drop dead . . . A week later Parish rode the wagon to work—and right over the toes of close chum Maxine Mesinger, the city’s reigning tsarina of tattle at the rival Chronicle . . . Parish personally broke the news of the impending snoop-out to Mesinger, and since then the air between them has been chilly enough for superconductivity . . . Max’s frosty reception notwithstanding, Parish has quickly become Houston’s hot media personality, mixing the usual neo-celebrity sightems with witty, irreverent insights into the comebacking post-bust metropolis. (Does that mean Houston is now in its post-post-boom era?) . . . Now even boss Burgin admits that a social sleuth can be a bottom-line bonus. In the six months since Parish has been on the job, the Post has been the fastest-growing big-city daily in the entire USA. (A Post boom in post-post-boom . . . awww, fergit it.) Sez new-believer Burgin: “I think you can lay a lot of that on Betsy.” That must be why Houston hoity-toits are now tripping over their Bruno Magli’s to get boldfaced by Betsy.

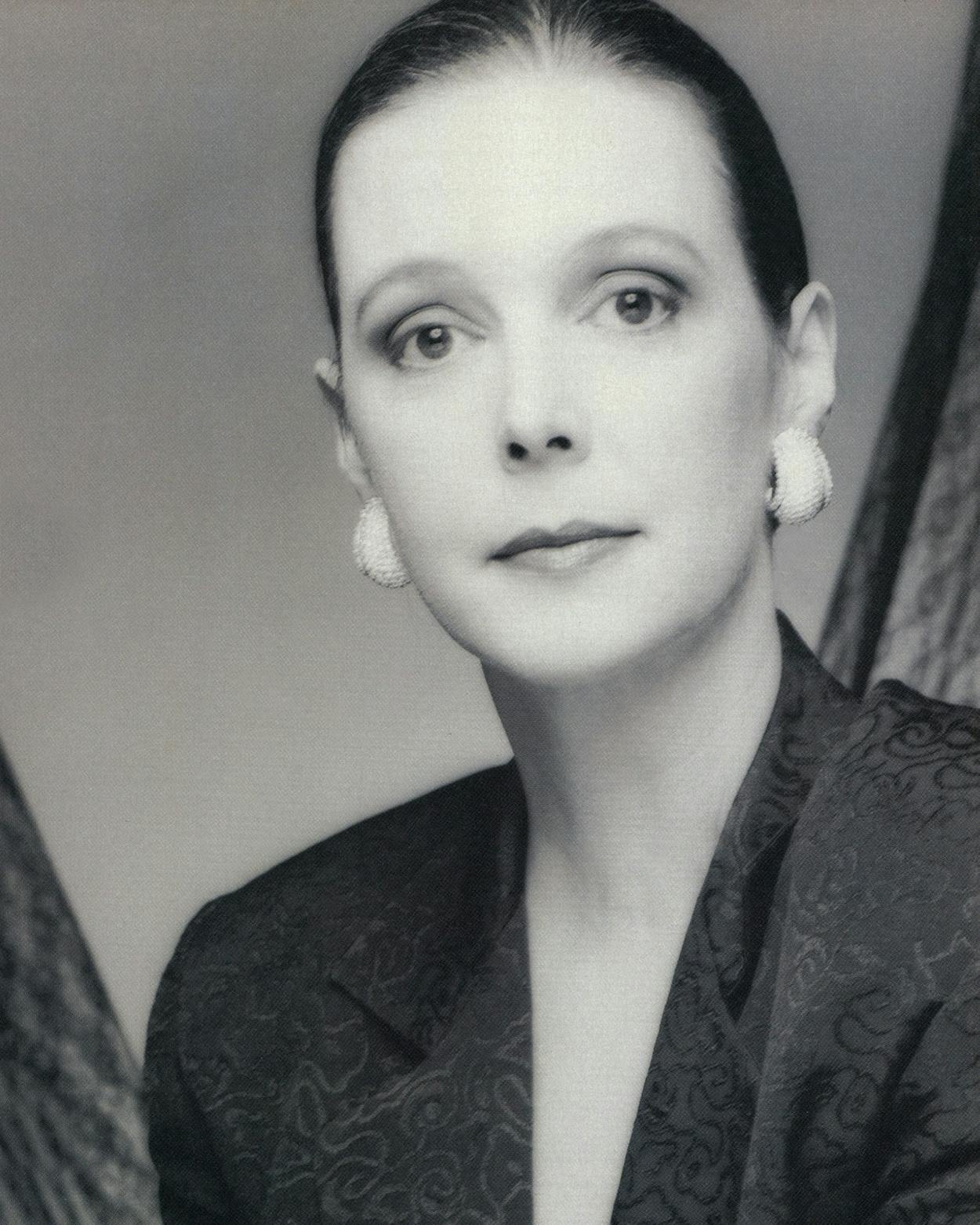

“Good evening, Miss Parish,” said the radio-equipped head parker as he swung wide the door of the long blue Lincoln Town Car. On this predictably steamy Saturday evening in late May, Miss Parish had just arrived at the Louis Pearce Ranch south of Houston. We are here for the first annual Cattle Baron’s Ball, which would benefit the American Cancer Society (in her column Parish has acknowledged the ubiquitous pretext of grave illness to late twentieth-century social extravagance by calling such events “disease balls”). Parish had layered some massive Navajo jewelry over a voluminous blue denim blouse with matching skirt, a memento of her “previous life”—before she took on the column, when she was forty pounds heavier and had countless fewer “new best friends.” With her classically pretty features, pale skin, and long dark hair pulled straight back, Parish—43 and single—has a look of Old South fragility and innocence that is immediately challenged by her whiskey voice, frequent savory laugh, theatrical gestures, and nonstop wisecracking. Post editor-in-chief C. David Burgin’s description of her as a cross between Holly Golightly and Auntie Mame is apt.

The sponsors of the Cattle Baron’s Ball were being hosted at a pre-party on the surprisingly well-groomed lawn in front of a suspiciously blue little lake—it turned out that the water had been dyed for the occasion. After ordering a Perrier and bantering with two of her “Parishioners”—a network of sources, many of them old friends who are regularly credited for items in her columns—Parish waded into the crowd, which she described as “the young guard of the old guard,” an assortment of local juniors like Walter Mischer, Jr., and Lloyd Bentsen III, along with various formers like former governor Mark White. The typical subdued interpretation of the Western theme was polished cowboy boots, pleated khaki slacks, and a starched plaid shirt, or a chambray dress and a bandanna around the neck. One heard only curious vestiges of the wheeler-dealer élan of a decade ago: “She’s just bought a starter farm,” a man remarked of his date.

Part of Parish’s appeal is her readiness to poke fun at the relative impecunity of Houston’s upper crust. Two weeks earlier she had run this item as her lead: “With River Oaksians pawing through bargains galore at the liquidation sale in progress at Frost Bros. on Shepherd, it was hilarious to hear the following announcement over the loudspeaker: ‘Attention all Frost Bros.’ shoppers! For the next 20 minutes, an additional savings of 20 percent in the fine jewel area.’ Now I ask you, can K mart’s blue lights be far behind?” But if Parish’s post-post-boom Houstonians are no longer so very rich, they are also no longer so mythically vulgar. In an early column she registered this complaint: “For the life of the Contessa [the Contessa is a Parish alter ego], she cannot remember a wedding or a celebration (excluding the rodeo) in Houston where everyone yelled ‘Ya-hoo!’ Yet in Suzy’s column about The Wedding of Mercedes Kellogg and Sid Bass she says that’s what ‘happens when exuberant Texans celebrate.’ Hmmm, should we protest the inaccuracy?”

There are few inaccuracies in Parish’s take on Houston; above all else, she knows the territory. Her great-great-grandfather was among the original group of settlers that the city’s primordial developers, the Allen brothers, lured from back East in 1838. Her grandfather Al Parish, Sr., was a managing partner of the Baker and Botts law firm, from which “cousin Jimmy” stepped to bigger things. Parish’s father, oilman and lawyer Al Parish, Jr., died when she was an infant, and her mother married food broker Hugh Alexander. Parish attended Kinkaid school and Lamar High School, then dabbled in college and modeling for several years. Instead of marrying well, Parish decided to work hard in a succession of PR jobs, but even then she moved in the orbits of the city’s rich and powerful men: Judge Roy Hofheinz’s AstroWorld Hotels in the late sixties; John Mecom, Sr., and Jr.’s Houston International Hotels in the early seventies; and merchant prince Robert Sakowitz, for whom she was vice president in charge of sales promotion, advertising, and public relations during the vertiginous boom-and-bust cycle of 1976–84. “He always had incredible clairvoyance in knowing what a trend will be,” Parish says of Sakowitz. “He even declared Chapter 11 before it became fashionable.”

After about half an hour of circulating among the Cattle Baron’s Ball’s sponsors, who uniformly greeted Parish with “I love your columns” and everyone else with “Nice to see you again,” Parish stopped to chat with tanned, white-haired ranch owner Louis Pearce, who was wearing a monogrammed blue windbreaker and denims tucked into the tops of his monogrammed boots. Pearce mentioned that he bought his spread 51 years ago. “Everybody tells me I had real foresight to buy back then,” said Pearce. “Foresight? If I’d had foresight, I’d have bought it northeast of town. It’d be a subdivision by now.”

When the conversation with Pearce ended, Parish asided that she would not be staying much longer. “I’ve got my item,” she said and gave a little cackle as she recounted Pearce’s good-humored self-deprecation. The item ran in her column the following Tuesday, and it conveyed just the right tone for Betsy Parish’s Houston: You don’t need to tell us we’re not exactly bidness wizards. But we can laugh at ourselves.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” says editor Burgin. “We had a hit on our hands from day one.”

As the thousands of revelers began arriving for the main event, Parish made a whirlwind tour of the facilities: gambling tables and a ballroom in the sprawling steel equestrian arena, dining tables beneath an adjoining tent. She checked in with various Parishioners, pausing at the entrance to the arena for a long, whispered conference with a man and a woman. Later she explained that the couple had the goods on a powerful Houstonian with a secret second family. Parish decided against publishing the item, although she was certain the story was true. “When you know someone is of a litigious nature, you don’t touch the stuff,” she said. Not that she doesn’t encourage scandal. The next morning she would run this item: “Speaking of search parties, call off the local all-points bulletin for former La Bare dancer Eddie Fenn (a k a ‘The Mighty Cougar’). The aspiring actor and model has abandoned the ladies in Our Town for opportunities beckoning from the European stage and screen. Hmmm. The Contessa says this item will quash those rumors about his living secretly with some married boldfaced type in Houston. Oh, really? Others say the couple will work out their separation problems. Oh, yeah? Which couple?”

At eight-thirty, as the late arrivals were still straggling in, Parish called for her car. “She’s ready to go,” snapped the head parker into his walkie-talkie, not needing to explain who “she” was.

On the drive back to town Parish talked about post-post-boom Houston, which has developed impressive cultural muscle out of its low-fat economy. Uniquely among Texas cities, Houston has started to pay as much attention to the business of culture as to the culture of business. “We’ve learned we’ve got to depend on something besides this genius for business, which we all thought we had and which we all found out we don’t,” Parish remarked. “The cosmopolitan personality of the city is the phoenix from the ashes of the bust.” When Parish started at the Post, she quickly realized that the competition wasn’t paying much attention to that personality, and in her column she turned the city’s artists, performers, and arts administrators into boldface celebrities. David Gockley, the Houston Grand Opera’s general director, is as big a star in Parish’s universe as any of the city’s real estate or oil potentates.

Parish made a few calls on her portable purse phone and then headed for the River Oaks Grill, a fashionable watering and feeding stop. She was greeted by owner Judy Orton, who quickly gave Parish the boldface briefing: “Peter Marzio, sitting against the wall.” Marzio, the director of the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, and his wife, Frances, were dining with Caroline Law. Caroline and her husband, Ted, had just given the museum a $3.25 million parcel of land for expansion; Parish had broken the item in her column.

But the Parish item over which the River Oaks Grill was presently atwitter was her account, published two days previously, of a meeting between Houston’s most celebrated divorced couple: “Carolyn Farb walked across the Rivoli to greet ex-husband Harold Farb with a kiss. Not on the cheek, mind you. Aannndddd smack dab in the middle of Wednesday’s packed lunch hour. Honest. According to Parishioners, it was theater at its finest.” This is typical romance Parish-style; some of her most mordant moments are reflections on post-modern sexual combat: “Overheard in the ladies’ room: ‘He’s a member of the country club, he drives a BMW, his ex-wife has remarried, his children are grown—on paper he’s perfect.’ If they knew his exact Dun & Bradstreet rating, it wasn’t mentioned. . . . Don’t tell me, or that particular bachelor, it’s not a jungle out there.” Two weeks later Parish added this equal-time remark: “Overheard from a femme sole on Valentine’s Day at a yupscale location for libation, ‘There are three kinds of men in this town: married, gay, and pond scum.’ ”

One reason Parish overhears so much is that her correspondents are not limited to the high and mighty. Because of her years in the hotel and PR businesses, she knows the names of a startlingly high percentage of the waiters, maître d’s, valet parkers, limo drivers, and security guards on her beat, and she frequently gives them boldface recognition. While finishing her salad at the River Oaks Grill, she was greeted by Victor Batista, the manager, whom she had befriended years ago when he was a waiter. “You made me a star,” he effused. The bartender also chatted familiarly, tipping her off to a weekly Thursday night waiters’ powwow at Houlihan’s. Parish accepted the invitation to attend. “Good night, Tom,” she called to the security guard in the parking lot on her way out. “People think that the help doesn’t notice things,” she said as she drove off. “They’re wrong. When I worked at the Warwick [John Mecom’s flagship luxury hotel] we knew everything that was going on in every room.”

Shortly after eleven Parish arrived at the bar at the Ritz-Carlton (formerly the Remington). Here she was invited to join dark-suited real estate magnate Harold Farb and his steady, realtor Diane Lokey, who was wearing a polka-dot Valentino. “You look so good you must have had plastic surgery,” Farb said genially. “You know, my secretary, Mary, takes a lot of abuse,” he went on in a wry tone. “It’s terrible what she has to put up with. Yesterday this woman called my office, and my secretary took the call. This woman accused me of planting that item about kissing my ex-wife at the Rivoli. This woman was pissed.” Farb left little doubt that the pissed-off woman was his ex-wife.

“I don’t have time to read the paper,” Lokey said demurely. “But I heard it was a mad, passionate kiss.”

Farb turned to his date and stammered momentarily. “It wasn’t a mad, passionate kiss,” he said sheepishly.

The story of how Parish became a columnist is an item in itself. David Burgin, a gruff, peripatetic news veteran—“He reminds me of Lou Grant,” says Parish—who had previously been the editor of the Dallas Times Herald for Post owner William Dean Singleton, had been on the job for less than a week when Marge Crumbaker decided to devote full time to the inn she owns in New Braunfels. Informed that Crumbaker had resigned, Burgin asked whether it was really that important for Houston to have a society columnist. Yes, he was told, look at Maxine. Burgin’s response: “Who?”

Strangely enough, that skepticism was coming from a self-professed item-column nut. Burgin had specialized in launching three-dot upstarts, most recently Rob Morse at the San Francisco Examiner, who has emerged as the first viable challenger to the San Francisco Chronicle‘s legendary Herb Caen. Burgin changed his mind about the marketability of gossip in Houston shortly after he was introduced to Carolyn Farb at the Remington Bar. When Farb told him that she had taken journalism courses in college, he offhandedly suggested that she apply for Crumbaker’s position. Farb invited Burgin to lunch at the haut monde Cafe Annie to discuss the matter further, putting the local rumor mill into overdrive. Within days, publications like Women’s Wear Daily had called to check out the socialite-turned-columnist tale, and Burgin had received dozens of applications from what he described as “a virtual who’s who” of Houston society. “I milked it for the publicity,” admits Burgin, who had Farb write several sample columns but didn’t see what he was looking for. “Finally, I realized that ripping Carolyn off was not a nice thing to do.”

Meanwhile Parish, after considerable urging by her friends, decided to enter the sweepstakes. She drafted a “namby-pamby” letter, thought better of it, and then sent Burgin an inquiry that began: “For the past ten years many of my friends and cohorts have told me that I should be the person to take over Marge Crumbaker’s job should she ever leave. If it was so apparent to them, I thought you would have called by now.” When Burgin summoned Parish for an interview, he found that she shared his admiration for Herb Caen and was a skilled raconteur. “We swapped stories for an hour and a half,” he says. Parish agreed to write four or five sample columns, and although her previously published works had consisted of press releases and the “Ultimate Gift” section of the Sakowitz Christmas catalog, Burgin discovered that his born storyteller was also a three-dot natural. “She stunned me with her brevity,” he says. “She didn’t need seventy-five words to set up a single quip.”

Parish’s debut column was set for December 4. On November 29 she was given a mandatory physical and was astonished to learn that her blood pressure was so hazardously high that she wouldn’t be permitted to start work. Back home, she was even more surprised when Burgin called thirty minutes later and ordered her to go to a hospital emergency room; he wouldn’t explain why. When Parish got there, she found out that the doctors feared an imminent stroke. The problem eventually was traced to a combination of thyroid and blood-pressure medications Parish was taking. But the doctors warned her that if she didn’t give up her almost daily regime of cocktails, dinner wines, and after-dinner drinks, she would soon find herself in another life-threatening situation. One young doctor cautioned her to prepare for classic alcohol-withdrawal symptoms. Parish was incensed. “Here was this intern talking like I was going to start shaking and seeing one-hundred-and-thirty-pound roaches. When I got out of the hospital, I looked all over for a giant plastic roach to send to him.” Parish went cold turkey with no ill effects; the alcohol-free diet pared off forty pounds over the next five months. She started her column on December 12 with a quote she credited to local rabbi Hyman Judah Schachtel: “Forgive your enemies, but never forget their names.”

Burgin assiduously coached his neophyte columnist, but even he wasn’t prepared for her sudden popularity. “With all the columns I’ve launched,” he says, “I’ve never seen anything like this. Looking back, I realize that we had a hit on our hands from day one. I just wouldn’t let myself believe it.” Parish didn’t believe it at first either, but she began to feel comfortable in mid-January, when she was thrown into the crucible of inauguration-gala Washington. She spiced her dispatches with instructions on how to greet famous personalities (“. . . fake familiarity and simply say, ‘Hello, nice to see you again,’ and go about your business. You’ll be interested to know you also can expect the standard issue response, ‘Nice to see you, too!’ ”), an item on a prominent D.C. prostitute (“Just thought you might want to know what else was going on in the capital city”), and this commentary on the eagerly solicited visibility of Houstonian Georgette Mosbacher, the wife of the new Secretary of Commerce: “If you ask me, this inauguration may be officially called the American Bicentennial Inauguration—From George to George, but if the media blitz on Madame Mosbacher continues, it soon will be known as: From George to George to Georgette.”

Parish’s tongue-in-cheek, Houston-wise insouciance has also given her paper a new personality. “The Post was perceived as cold, distant, timid,” says Burgin. “In that context Betsy has done more to warm up the paper than any other single thing. She has enormous wit and charm, and it comes right through. She can twit and throw her head back and laugh. You can tell Betsy doesn’t take herself seriously. And in this town, that’s essential.”

Parish does take the job seriously. She works in an office set up in a spare bedroom of her new midrise condominium; her widowed mother lives in the unit just above her (“My mother says I’m always underfoot,” she says). To have the column ready six days a week, she gets up about seven and for two hours goes through the New York Times, both Houston papers, and a variety of magazines. Then she calls her answering machine at the Post, collects the first batch of the fifty to one hundred phone calls she receives at that number each day—she also gets another forty to fifty daily at her unlisted home phone—and starts returning calls. She sits down at her word processor about noon and usually has her column done by three. After she transmits her column to the Post, she goes through the fifteen to twenty pieces of mail she gets each day at home; once a week she picks up a shopping bag full of mail at the Post. Parish usually goes out six nights a week, moving quickly from place to place. Her axioms for maintaining her on-the-town pace: “Don’t drink. And don’t get stuck. I rarely go to seated dinners.”

The day after the Cattle Baron’s Ball Parish did get stuck, at a benefit dinner for the Houston Gulf Coast chapter of the National Foundation for Ileitis and Colitis, an up-and-coming cause that has new cachet because President Bush’s son Marvin suffers from colitis. The event was held at Tony’s, Houston’s most prestigious dining spot. This meant that Parish most likely would be crossing paths with Maxine Mesinger, who, even by Parish’s admission, made Tony’s and who still rules the Gaza Strip, the elite rows of centrally situated tables.

Parish calls Mesinger the grande dame of Houston gossip columnists, and indeed she is. In the mid-fifties Mesinger, then a local television personality, started doing legwork for gossip columnist Bill Roberts at the now-defunct Houston Press. She took over Roberts’ column in 1959, when he moved to the Post, and had a highly publicized feud—Time did a story—with her ex-boss when she started out. Mesinger moved to the Chronicle in 1964, and her “Big City Beat” established her as perhaps the most powerful nonsyndicated regional columnist in the country. Using her extensive show-biz connections and her network of local sources, Mesinger created a glitzy, unabashedly nouveau-riche Houston where birthday celebrants at local “swankiendas” shared boldface status with Max’s Hollywood chums.

During her PR years Parish dined often with Mesinger and Mesinger’s husband, Emil; one of Mesinger’s best sources was Parish, who regularly sent her items gleaned from her own network of friends and acquaintances. Whenever Parish commented enviously on the deferential perks Mesinger enjoyed—front-row seats at the opera or the best table in a restaurant—Mesinger would always reply, “Get a column.” The same day Burgin offered Parish the job at the Post, Parish joined Mesinger, Emil, Houston society doyenne Mary Greenwood, and Town and Country writer James Villas for dinner at Segari’s Seafood Restaurant. Parish told Mesinger, “You remember how you always used to tell me to get a column? I just got a column.”

“Then this is our last supper,” replied Mesinger.

Parish seems genuinely wounded by the distance Mesinger has maintained since then, and she has made such conciliatory gestures as boldfacedly wishing Maxine a happy birthday in her column. But she is also obviously proud of the subtle contrasts between her style and Maxine’s—she prints correction notices for misspelled names, and Maxine doesn’t—as well as more profound differences. “I don’t think I’m a celebrity,” Parish says somewhat archly, “although some people in my position think they are. I don’t use a lot of Hollywood names, because my goal isn’t to be syndicated nationwide. I can accomplish my goals by just being a Houston columnist. Other Houstonians have made a success of just being from Houston.”

Most of the mega-diamonds in view at the Ileitis and Colitis Foundation dinner were loaners from Tiffany’s and were being modeled by foundation members. Former governor Mark White was again on hand, as were Harold Farb and Diane Lokey, tonight in a Geoffrey Beene. Farb took aside an out-of-towner, looked around quizzically, and then inquired conspiratorially, “Do you know any of these people?”

Mesinger and Parish had been sighted greeting each other in the middle of the Gaza Strip at Tony’s the preceding week, and at that time Mesinger had volunteered, “We’re good friends,” to the curious onlookers. But on this evening when Mesinger entered, she and Emil passed magisterially on the opposite side of the table beside which Parish was standing. Neither woman acknowledged the other.

The multi-course meal progressed pleasantly; the extended planters that defined the Gaza Strip had been removed, and Parish sat at a table on one side of the main room while Mesinger held court on the other. The eponymous Tony Vallone and the Tiffany’s rep moved solicitously among the tables. The hot rumor of the evening was that Dr. Red Duke, the Houston telemedic who was sitting with his very blond wife, Pam (the former wife of real estate magnate Kenneth Schnitzer), just a table away from Parish, was on the short list to replace Surgeon General C. Everett Koop. The big announcement, however, was that George and Barbara Bush and son Marvin and his wife, Margaret, would all appear as honorary chairmen of the Ileitis and Colitis Foundation Winter Ball (the organizers would have been thrilled to have just one Bush on hand).

After dessert Parish crossed the room to pay her regards to Mesinger. There was an awkwardness in both women’s similarly throaty, ordinarily mellifluous voices as they exchanged greetings and attempted to joke. Mesinger froze over when she learned that a story on Parish was in the works. “Always good to see you,” Mesinger said as Parish took her leave. “Always good to see you,” replied Parish.

The Post clearly has upscale ambitions for Parish after her fast start. “My idea is for Betsy to take it in the direction of Herb Caen, who’s sort of the conscience of his city,” says Burgin. He is also already cautioning his protégée about an occupational hazard: He made her get a video of The Sweet Smell of Success, in which Burt Lancaster plays a villainous three-dot despot (allegedly based on Walter Winchell) intoxicated with his power to make and break reputations.

The night after the Ileitis and Colitis Foundation dinner, Parish was off to a cocktail party at former boss Robert Sakowitz’s River Oaks manor. “It’s the first time I’ve ever been invited to enter that house through the front door,” she said in anticipation. But if Parish has a wry sense of her sudden power to flout the rich after all those years of flacking for them, she can also look back on her service in the PR trenches with the equanimity of a survivor: “I feel like everything I’ve done in my life has been a preparation for this job.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Houston