This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Clarence Jones sat on his brightly flowered sofa with his suspenders unstrapped. He maintained his innocence with a slow, wondering roll of the head. “I’ve had the same job at Safeway for twenty-three years,” he said, “and we don’t have no trouble at home. We scuffling to make it, though. If I’d known there were all these inducements floating around, I ought to have had me some. They didn’t offer me nothing. They just said they gonna take care of my kid.”

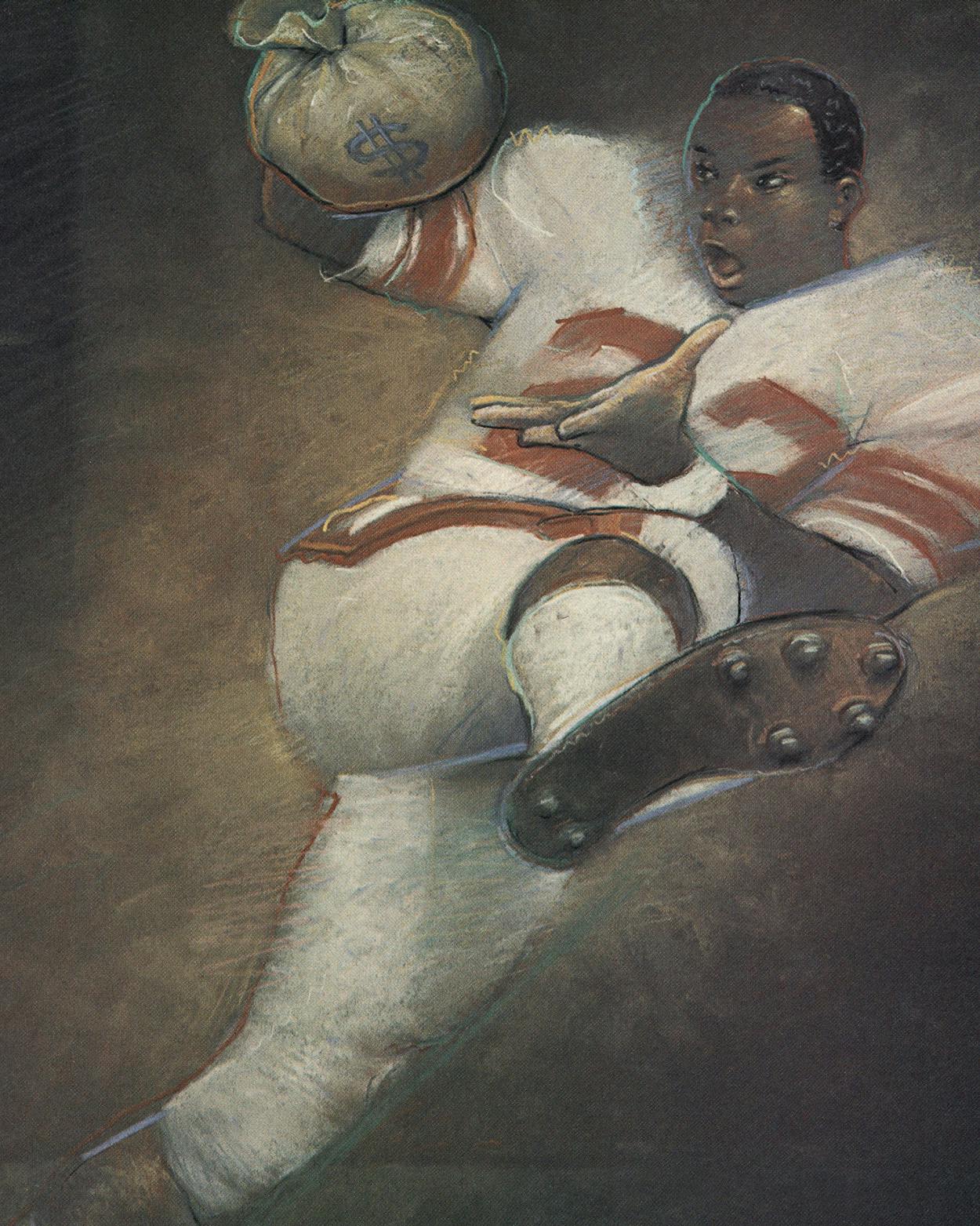

Photographs of the four Jones children crowded the walls of the cramped living room. Among the tassels and mortarboards, photographs of the youngest son, Roderick, were prominently featured. In one, he was wearing the gold football uniform of Dallas’ South Oak Cliff High; in another, the red and blue of his present team, the Southern Methodist University Mustangs. As a college freshman last year, Jones covered kicks on the specialty teams, subbed at cornerback, and intercepted one pass against North Texas State. That may not sound like all that much, but football coaches don’t allow just any player to wear number one on his jersey. The best demonstration of Jones’ potential came this past June at the National Collegiate Athletic Association track-and-field championships in Houston. Under pressure, his blazing 44.1-second anchor leg in the 1600-meter relay, the meet’s last event, not only brought SMU from behind to win the national title but established him as an Olympic-caliber quarter-miler. And unlike many track stars, he brings more to football than speed. “He’ll knock your shingles loose,” says one coach from a rival school.

Roderick Jones was signed in early 1982 by Mike Barr, an SMU assistant coach, and Sherwood Blount, Jr., a North Dallas millionaire realtor who played linebacker for SMU in the early seventies and is now an avid booster. Last year, SMU had an undefeated football team ranked second in the country, national titles in both indoor and outdoor track, a resurgent basketball team, and national runners-up in swimming and tennis. Those accomplishments shredded the notion that small private schools can’t compete with the large state-supported universities of the Southwest Conference. But the champagne quickly went flat. SMU has been on NCAA probation five times—a record second in the country to Wichita State’s. The football program has come under severe scrutiny by the NCAA three times in the past decade. Before moving on to the NFL’s New England Patriots, Coach Ron Meyer saddled SMU with a stiff probation by leading prospective players to believe that they could profit from selling their complimentary tickets, according to the NCAA. Two years ago Meyer’s last team won the conference but had to sit out the Cotton Bowl. And it didn’t help appearances when Southern Mississippi, the former employer of new coach Bobby Collins, also went on probation after Collins had accepted the SMU job. SMU finished its most recent term of probation in June, but the NCAA has launched yet another inquiry into Mustang recruiting practices.

“The coaches are ambivalent about alums—they are so helpful, yet so prone to break the rules and then brag about it. To alums, recruiting is a game of cheap thrills—even when they’re flashing money around.”

The all-American dream of raising a son to be a star football player can, for many families, turn strangely sour. The controversy surrounding SMU suggests the mood of constant recrimination, the sense of outrage, pervasive in opposing camps. Everybody breaks some rules, say the accusers, but those guys at SMU will stoop to anything. according to representatives of schools that failed to sign Roderick Jones, his father told recruiters that the Joneses’ kitchen floor was about to fall through. The whole room needed remodeling. Or, in another version of the story, maybe it was the bathroom. The inference, of course, was that SMU’s representatives gladly forked over.

Clarence Jones waved a hand in the direction of his controversial kitchen. Its door was meticulously overlaid with strips of white decorative tape. “When I heard about all this, my wife was in there putting up wallpaper she got on sale at Safeway.” A tiny, attractive woman with flashing eyes and mahogany skin, Merivonne Jones worked at Parkland Hospital. She appeared now in a long velour bathrobe. “Come on in here,” she commanded. “I want you to see for yourself.”

The kitchen was scrubbed and narrow. There was an old gas stove, and the linoleum on the floor was faded, cracked, and worn. “Keep on coming!” she cried, backing down the adjoining hall. “You got to see it all.” The bathroom appeared to have the greater need of repair; the floor sagged from the weight of the toilet. Obviously neither room had benefited from any sudden expenditures of money. Our tour of the small frame house ended in the front bedroom. Its walls featured plaques that honored Roderick as an all-American in high school track and large football posters from Arizona, Nebraska, and Texas Tech, as well as SMU.

“He ain’t no hardheaded kid,” Clarence Jones said. “He just couldn’t make up his mind. He liked all them schools. ‘Arizona’s got the best track facilities.’ ‘Down there at Texas, every player’s got his own bathroom in the dorm.’ ‘But it’s awful pretty up there in Colorado.’ He wanted to go to all of ’em—one a day. He broke down and cried. Well, it’s new to me. My wife and I don’t know anything except what’s in that handout he brought home from the N-C-Double-A. But he ain’t ever been away from home. So I encouraged him to go to SMU. He’s a Dallas boy, born and raised. They got good facilities, and they say he’ll play some ball. If he gets that education, there’ll be work for him here. Make something of himself. Be somebody. On down the road, when he gets on his feet, maybe he’ll be in a position to help out a little at home.”

He departed from this discourse, which would have warmed the hearts of recruiters and alums at SMU, by jabbing his finger at a stack of bills on the dining room table. “I can’t afford for that boy to go off to school. His long distance is about to eat me up now. He gets away on the weekends to them track meets and bills every call to me.”

“He’s just a baby!” the mother chipped in, her eyes ablaze with indignation. “He don’t even know how to wash his own clothes!”

The Ultimate Fraternity Rush

The cycle of recruiting begins in May of the high school players’ junior year. Working assigned territories, Southwest Conference recruiters call on high school coaches, watch films, observe spring training drills, compile and refine their lists of names. During this period, conversation with the potential recruits is forbidden by the NCAA, but the gifted players understand the significance of that extra guy with the stopwatch. They run their wind sprints with unprecedented enthusiasm.

It’s a fraternal profession—coaches enjoy the company of other coaches. In Dallas, many out-of-towners regularly book rooms at the Marriott on Stemmons Freeway. At the Point After, a Greenville Avenue haunt of coaches, sports-minded SMU alums, and occasional Dallas Cowboys, the recruiters talk shop and compare notes. Their bosses, the head coaches, are also on the road—shaking hands, eating steaks, talking about the upcoming season, rewarding the interest of local alumni clubs. Some days the recruiters have to drop what they’re doing and drive for several hours to play in the alums’ get-acquainted golf tournaments. By Friday they’re breaking the speed limit to get home for a couple of days with their families. It’s the life of a traveling salesman. And in this facet of their occupation, that’s exactly what they are.

While most schools retain a full-time recruiting coordinator who has no responsibilities on the field, the assistant coaches, with help from alums, do the legwork and deliver the goods. During the summer they take vacations, devise strategies for the season’s early games, and write ingratiating letters to those legions of prospective recruits. Correspondence continues, and phone contacts begin after the high school season starts in September. By now each college’s list may have four or five hundred names on it. After preparing for their own games, the assistant coaches hit the road on Thursday, try to catch parts of at least two high school games by Friday, and arrive back at the college stadiums just hours before kickoff.

By the end of football season, this game behind the scenes has just begun. NCAA regulations allow coaches six face-to-face contacts with recruits—three in the youth’s home, three on the high school campus. In the coaches’ view, the guidelines are inclined to the picayune. A coach can’t buy a kid a hamburger or offer him a ride in his car. A “bump,” or chance encounter on the street, can be construed as an official off-campus visit. Trickier still, if someone besides the recruiters conducts himself as a university’s “representative of athletic interests,” by the NCAA definition he has just become one.

In addition to the hometown contacts, the NCAA allows each college to entertain 95 prospective recruits on campus for 48 hours, at the school’s expense. But recruits don’t just pick up a prepaid ticket from the local travel agent. In years past an alum could shuttle them in his Bentley or Mercedes to the airport, where, if a university-owned plane wasn’t waiting, they often made the flight in a Learjet on loan from a rich alum. They might even have finished the trip in a helicopter that deposited them in the college stadium at the fifty-yard line. While they toured the campus, met faculty members, and talked about football with the coaches, for most of the weekend they were squired about by players already on scholarship. It’s the ultimate fraternity rush.

The players sign their letters of intent on the second Wednesday of February, and toward the end, the courtship takes on a circus quality. The coaches press the youths for verbal commitments that are legally meaningless and generally ineffective even as a competitive smoke screen. Sometimes, to sign a star recruit, they offer a scholarship to an influential but less talented teammate and friend—the stratagem is called “a cow and a calf.” The “kidnappings” that we hear about are mildly dirty tricks played by sympathetic proxies, often college players of the recruit’s acquaintance, who simply remove the prize youth from the premises; rival recruiters can’t change the kid’s mind when he’s constantly on the drag between Kip’s and the Dairy Queen. For many players, who both glory in and freeze up under all the adulation and pressure, the suspense of National Signing Date becomes a drama played out in the last hours between midnight and dawn. One recruiter recalls his chagrin at losing a top running back whose commitment he thought was secure: “Afterward I asked the kid how in the world that happened. He said his dad called him aside and said that he had to go to work in the morning, that he was sick and tired of all this, that the boy had to make up his mind. ‘And Coach, those other coaches, they were in the room.’ ”

However excessive it is, all of that is acceptable to the NCAA. The pattern of illegalities starts with the organization’s minor decrees. In the cutthroat competition of the Southwest Conference, many recruiters feel they’ll lose a top prospect if hands aren’t held every week. And who’s going to blow the whistle on violations of visitation limits? They all have as much on their rivals as their rivals have on them. This code of secrecy extends to larger infractions as well—which is not to say that recruiters have no standards of ethical behavior. It’s like the code of street cops: you may disapprove of many things you see and hear, but you hesitate to turn a buddy in. For one thing, the profession is in a constant state of personnel flux. This year’s opponent may be next year’s job opportunity.

The charity stops considerably short of the opponents’ alums, however. Coaches are ambivalent about their own boosters: alums are so helpful, so necessary, so prone to break the rules and then brag about it. When the NCAA imposes sanctions on a school for recruiting violations, it often includes an ultimatum to dismiss a specific coach. Yet when the alums are the culprits, the NCAA doesn’t name names in its press releases. For the coaches, college football and recruitment of players is a matter of livelihood. To the alums, it’s a game of cheap thrills—even when they’re flashing money around.

A professed cornerstone of the NCAA is the fairness of its athletic competition, and if affluent and unprincipled individuals are allowed to stack the rosters with the best athletes their money can buy, the scoreboards soon reflect that unfair advantage. The NCAA comes down hard on schools whose recruiters and boosters are found guilty of offering monetary inducements to recruits or their families. The structure of the enforcement program and the utilization of its limited manpower reflect that preoccupation with the incoming freshman recruits. Veteran players already on campus are not so easily scrutinized, as recruiters well know. Prudent coaches tell prospects, for example, that they’re not going to be able to deliver the keys of a new Trans Am as a bonus for signing the letter of intent, but if the player needs a new car to be happy on a particular campus, there are ways to help him make the payments. While the student on athletic scholarship can’t accept part-time employment during the academic term, some alum can provide a high-paying summer job. NCAA guidelines restrict that income to the prevailing market wage. The athletes often work hard for the money on freight docks or oil rigs. But sometimes a player may paint one door of a house and pick up a check for $1000.

In a second standard means of supplementing their income—equally open to abuse—the football players sell their four complimentary tickets to each of the team’s games. For successful teams that play before crowds of more than 50,000 people every week, the potential cash value of four tickets between the forties adds up fast. In the usual ticket scam, an upperclassman well connected with alums acts as a broker. In the worst cases, star players sell their tickets in a block before the season begins. Conceivably, income of that nature could approach $4000 or $5000 a year. This gray area of NCAA infractions—taking care of players, as it’s called in the trade—is far more prevalent than upfront inducements in the form of new cars and cash guarantees. But either way, in the cynic’s view, money moves from hand to hand.

“The prudent coach tells prospects he can’t deliver the keys to a new Trans Am as a bonus for signing, but later on if the player needs a car to be happy, there are ways to help him make the payments.”

A Vintage Highland Park Pitch

The intrigue of the recruiting game in the Southwest Conference involves the natural antagonisms between big fish and small fish. The University of Texas, with its awesome facilities, long and colorful winning tradition, and vast network of supportive and influential alums, would seem to have a substantial leg up in the recruiting wars. But the days of the big state universities’ absolute supremacy are over—and unlikely to return. The racial integration of Southwest Conference football enlarged the power base and invited a redistribution of the wealth. Blacks no longer had to leave the state to play major college football. The NCAA altered the equation more drastically by limiting the number of football scholarships to thirty a year. For years UT signed as many as a hundred players a year and was accused of recruiting youths who had no realistic chance to play for Darrell Royal—but who might have proved troublesome in the uniforms of Southwest Conference rivals. The new rule guaranteed the smaller schools at least the chance of an even break.

Though SMU’s renaissance has just begun, the dreams are still grandiose. Its pitch to young players is vintage Highland Park. Recruiters stress the polish and sophistication of Dallas and the advantages that Dallas confers on holders of the SMU pedigree. If a visiting recruit expresses career ambitions in real estate, finance, or law, he soon is shaking hands with a member of that profession who played ball for SMU and made his first Dallas million before his hair turned gray. A model for what SMU is attempting can’t be found in the Southwest Conference or, for that matter, elsewhere in the Midwest or South. But in Los Angeles, a noted private university mobilizes its alums as recruiters and, in competition for the city’s entertainment dollar, meets the challenge of pro football head-on. SMU intends to be the new Southern Cal.

A hallmark of SMU’s football resurgence has been its recruiters’ success in signing flashy black players for the “skill” positions—the wide receivers, running backs, kick returners, and cornerbacks who in today’s game can put a good team over the top. The ardent recruitment of two such prospects in North Texas may have helped bring this year’s campaign to grief.

In Cooper, a small town eighty miles northeast of Dallas, Ronald “Boom” Morris was having a terrible time making up his mind. The blue-chip wide receiver and state champion sprinter had led coaches from TCU, Texas Tech, and SMU to believe that he had committed to their schools. He had even received calls from Atlanta mayor Andrew Young on behalf of Georgia Tech. And then, on his official visit to the UT campus in Austin, Boom did it again. According to SMU sources, Fred Akers asked Morris in a room full of other recruits if he hadn’t always, deep down in his heart, wanted to play football for Texas. Sure, stammered the youth—at which point Akers encouraged the other kids to congratulate Morris on his commitment to the Longhorns.

UT recruiters were sufficiently concerned about the youth’s fidelity to ask the sympathetic Cooper track coach, Robert Gatlin, to go over to Morris’ house on January 30, the night he got back to town. According to Morris and his mother, Morris had called the UT coaches to retract his commitment by the time Gatlin arrived at their house. His visit interrupted a completely proper recruiting visit by SMU alum Bill Stevens, a Dallas banking consultant; to avoid any unpleasantness, the Morrises simply showed Stevens to another part of the house. Akers vehemently denies charges of manipulation; by his account, Ronald Morris had complained in that long distance call that Stevens was hassling them and refusing to leave their home. When Gatlin arrived, according to Akers, the SMU booster “ran and locked himself in the bedroom.”

Meanwhile, in Fort Worth, TCU coaches thought they had the inside track with Morris. Recruiter Jim Dawson, who had come from Southwest Texas State with new head coach Jim Wacker, had the help of Ronald’s older brother, J. C. Morris, a halfback who had just completed his eligibility at TCU. At least they hoped J.C. was on their side; he was disgruntled by the treatment he had received from the regime of deposed coach F. A. Dry. And the older brother had whisked Ronald away from the TCU campus during an unofficial visit before Wacker had had a chance to make his pitch. Dawson said that when he heard about the Texas commitment, J.C. assured him, “Don’t worry. He’s just doing that because he doesn’t like Coach Akers.”

Ronald advised recruiters from all three schools to attend Cooper’s basketball game in Quitman on February 8, the last night of recruiting season; he would announce his decision then. The college recruiters showed up as ordered in the tiny East Texas gym. In the spirit of their comic predicament, the UT and TCU coaches even sat together in the stands.

Ronald Morris skipped out on those coaches after the game and left them hanging that night, but the next day he joined 22 other recruits in signing with SMU. Bobby Collins and his staff were ecstatic; they felt this freshman class compared favorably with the Eric Dickerson–Craig James coup of 1979. But the SMU coaches had little time to rejoice. Bob Minnix, a former Notre Dame halfback who is now a lawyer and an NCAA investigator, had been monitoring recruiting in Texas as a part of Operation Intercept, in which the enforcement division chaperons the courtship of the top 150 prospects in the country. While making the rounds, Minnix had called on an old friend, Tony Sexton, an assistant coach at Rice. Sexton was extremely bitter about his loss to SMU of a wide receiver from Dallas’ Kimball High named Marquis Pleasant. Sexton informed Minnix—and later told several reporters as well—that Pleasant on two occasions had told him about an SMU booster who offered a Camaro Z28 in exchange for his letter of intent. “Marquis told me,” Sexton said, “the alum drove it up in the driveway and said, ‘Sign the paper and the car is yours.’ That’s right out of Marquis’ mouth.”

Rice head coach Ray Alborn promptly ordered his staff to stop talking publicly about recruiting. Marquis Pleasant claimed that his mother had paid for the 1980 Camaro he was driving. SMU boosters were furious; they countered that Sexton himself had made a shambles of NCAA recruiting rules by arranging for Pleasant’s fiancée to visit Rice with the youth—and then by suggesting that she would find abundant job opportunities in Houston if Marquis chose to enroll. But for the SMU supporters, the ominous reaction of the NCAA investigator seemed almost preordained. Bob Minnix told the press that while he had no firsthand knowledge of Marquis Pleasant’s recruitment, he could vouch for the truthful reputation of Tony Sexton.

The Pot Calls the Kettle Black

In February Dan Beebe, the NCAA investigator who would handle the subsequent inquiry, asked questions in Cooper, Austin, and Lubbock about the recruitment of Ronald Morris. Like Minnix, Beebe is a young lawyer who played college football, at Cal-Poly in Pomona. Supported by a part-time staff of 25 former FBI agents, the enforcement division’s 10 field representatives work out of the NCAA’s headquarters in Shawnee Mission, Kansas, a suburb of Kansas City. These detectives have a ticklish responsibility. They operate with the consent of the organization’s member universities; they dig up dirt on the institutions that collectively employ them. They are like a private security force, not a law enforcement agency. Most of the “illegalities” that these investigators track down are against nobody’s law but the NCAA’s. The NCAA investigators don’t use lie detectors, and they don’t have subpoena power. The only people who have to cooperate with them are the coaches, who can lose their jobs, and the athletes, who can lose their eligibility. Flooded with tips and leads, almost all of which come from highly biased sources, the investigators explore this morass of rumor with elaborate caution. They take their time—there’s no statute of limitations. And ordinarily, to the benefit of both the investigators and the investigated, they ask their questions in relative secrecy. The last time SMU was under fire, the NCAA’s investigation was a year old before the public found out.

But not this time. On March 10 Bobby Collins and SMU president Donald Shields received confidential form letters from the NCAA advising that the school’s recruiting program was under preliminary investigation. A WFAA-TV producer, John Sparks, broke the story the next day and, with a team of sportswriters from the Dallas Times Herald in hot pursuit, predicted that the investigation would center on the recruitment of Ronald Morris in Cooper. A Cooper High School official and a Southwest Conference assistant coach told the Times Herald that Morris had described a mid-January clandestine meeting in which an SMU booster had offered him $4000 for signing and $400 for every month he was enrolled in the school. In the office of President Shields, who was just then putting the final touches on an ambitious five-year plan to upgrade SMU’s academic reputation, the news must have been about as welcome as an outbreak of cholera. The school’s last term of probation still had three more months to run. SMU retained Dallas lawyer John McElhaney, who had defended the school on the previous occasion, to conduct an internal investigation.

One day SMU athletic director Bob Hitch was explaining the internal investigation to the TCU staff when head coach Jim Wacker erupted in a tirade about SMU’s recruiting practices. Wacker wasn’t merely sore about losing Ronald Morris. Ever since December, when he’d arrived from Southwest Texas State, Wacker had been on a soapbox about Southwest Conference recruiting. In fact, during early March he had mailed a letter to each of the conference head coaches admonishing them, as a group, to take corrective action. In a subsequent interview with the Times Herald, Wacker summarized the thrust of his letter: “There’s no doubt there are minor violations. They’re inevitable. But the major—you know, the blatant buying of athletes—has to come to an end.” Asked if he relished his role as self-appointed crusader, the TCU coach effused, “Son of a gun, heck, no. It would be a lot safer for Wacker not to say anything. I knew I was taking a heck of a chance. I’ll guarantee you there’s some people saying right now, ‘That self-righteous son of a gun.’ ”

The reaction to Wacker’s letter was downright chilly. “It’s an admirable posture,” commented Houston’s Bill Yeoman. “But the thing is—and I dropped him a note—he should make sure everything at his place is fine and I’ll make sure everything at my place is fine.” Yeoman was saying with droll sarcasm what SMU boosters were fairly spewing: here was an outlandish case of the pot calling the kettle black.

If Wacker has cleaned up his own house, SMU partisans charge, he has worn out truckloads of brooms. During the regime of head coach F. A. Dry, TCU boosters had the conference tongues clucking. Recruiters liked to swap yarns about Dallas’ Dick Lowe, president of American Quasar and for many years TCU’s Mr. Big, and about Chris Farkas, a Dallas–Fort Worth restaurateur who drives a Rolls-Royce and is known by the TCU players as the Pizza Man. The most heated speculation centered on TCU’s recruitment of Egypt Allen, a star running back from Dallas’ South Oak Cliff, and on the school’s forays among the California junior colleges, whose players often demanded to know who was going to pay for the plane fare for their regular visits back home. When Wacker pulled his recruiters out of that West Coast jungle, Texas Tech coaches reportedly showed up in their place. And what about A&M? In Houston federal court on May 16, an administrator of baseball’s Milwaukee Brewers—who were trying to reclaim the contracted services of third-string Aggie quarterback Kevin Murray—claimed that Murray told him Aggie boosters had supplied a 1980 Buick Regal, gasoline and Visa credit cards, and $200 a week while the athlete was still a senior at North Dallas High.

And that became the SMU boosters’ standard line of defense: our guys haven’t done anything that the accusers’ recruiters and alums haven’t done. The conviction that SMU was being treated unfairly by the NCAA was most fervent with respect to Texas. UT partisans are proud of the school’s reputation for holding the line against recruiting inducements. But in that other area of NCAA infractions—taking care of the players—the holier-than-thou posture is a sham. Surrounded by solicitous alums, every player on the Texas team knows that, at the very least, he can collect between $500 and $800 every year for his four tickets to the Oklahoma game. By selling tickets to other games, some players, particularly the stars, do better than that. Last year, Oklahoma running back Marcus Dupree claimed that two UT coaches had bought him a pair of $143 cowboy boots. The NCAA was unable to establish guilt, but it imposed a year of probation as a caution to UT. At the same time, it was also revealed that Johnny “Lam” Jones had scalped fourteen of his free tickets in 1978–79. To SMU it was significant that UT did not receive the more punitive penalty of sanctions for the violations.

According to this view, the NCAA’s enforcement division is a tail wagged by the big dogs of the organizations—particularly UT, whose favored treatment has been ensured by the position of Charles Alan Wright. The chairman of the infractions committee that reviews the enforcement division’s evidence and makes the final decision on probation and sanctions, the UT law professor also designed the NCAA’s procedure to bring it in line with standards of due process. From the NCAA’s viewpoint, the enlistment of a renowned constitutional scholar like Charles Alan Wright lends immense credibility to the enforcement program. But to SMU partisans, the only significant aspect of Wright’s background is his employer: Texas.

“Based on my limited experience,” commented SMU president Shields, “I’d say that all the member institutions are not monitored . . . equally.” Former Mustang star Craig James, returning from his rookie year in the U.S. Football League, was less politic in his assessment: “At SMU, we’re no cleaner, we’re no dirtier. We’re the same as the University of Texas. We’re the same as TCU, as Houston, as A&M. We just don’t have the people in Shawnee Mission, Kansas, that some of these other schools do.” James continued, “I think we’re showing a whole lot more class by not being tattletales on the University of Texas . . . Why don’t they live up to their reputations as big boys and just play football?”

A Smoking Gun?

On April 28 the civil courts building in downtown Houston presented the usual array of sweating lawyers in pin-striped suits, personal injury plaintiffs with whiplash neck braces, and witnesses asleep on hallway benches with the remains of the morning newspaper shoved messily aside. But outside the courtroom of state district judge Wyatt Heard, an air of strange festivity prevailed. Talking to reporters was another state district judge, Neil Caldwell, a former Democratic legislator from Angleton. Back in the fifties, Caldwell was a freshman walk-on at the University of Texas in football and track.

In his days as a state legislator, Caldwell occasionally wrote letters on behalf of UT to coveted high school players in his constituency. A couple of years ago, standing in line for a school board election, the judge ran into the parents of David Stanley, an all-state linebacker and record-setting discus thrower at Angleton High. Caldwell told the Stanleys, who had once run the coffee shop in Angleton’s Brazoria County Courthouse, that he sure hoped David would go to UT. Later he tried to arrange a tour of the Burnt Orange Room for David when he was in Austin for the high school track meet. But Caldwell wanted the reporters today to understand that his subsequent visit in the Stanleys’ home had nothing to do with the athletic interests of UT. Otherwise the university could be held in violation of the NCAA’s visitation rules.

Caldwell was clearly enjoying himself. Approaching their courtroom appointment, Kenneth Corley walked fast and stared straight ahead. With short hair, an outdoorsman’s tan, and broad shoulders snug in a blue knit shirt, Corley looked like a high school football coach. In truth he is a Texas City used-car salesman who, at the peak of Southwest Conference recruiting activity early this year, took his young friend David Stanley to Lake Tahoe, Nevada, where the Angleton High School linebacker walked away from the gambling tables with $2000. The purpose of the trip, according to Corley, was to give the youth a break from the terrible pressures of collegiate recruiting. Texas was in hot pursuit of David Stanley’s signature—which ultimately went to SMU. The car salesman has a brother in Austin, Jim Corley, who calls on the UT athletic department as a coffee vendor. Jim suggested to UT recruiters that SMU supporters were behind the Tahoe escapade.

UT recruiting coordinator Ken Dabbs called a prominent Freer booster, Carroll Kelly, who in turn contacted Neil Caldwell in Angleton and asked him to see what he could find out. After asking around town about Corley, Caldwell called on the Stanley household. David Stanley’s father said he’d done some checking himself and had come to the conclusion that nothing was amiss. David Stanley talked about his hopes of playing pro football. Caldwell claims he merely advised the youth to avoid running with the wrong crowd. But four days later the judge received a call in his office from Corley, who said he understood Caldwell had told the Stanleys that he, Corley, smuggled cars across the border and sold dope. If Corley didn’t receive a written apology, he intended to sue the judge for slander.

In Texas, when a lawsuit is reasonably anticipated, the defendant can instigate sworn depositions. Corley had just handed Caldwell subpoena power—an essential tool that NCAA investigators lack. In a fairly brazen manipulation of the legal process, the judge filed his petition in the court of a colleague down the hall, Judge J. Ray Gayle. Caldwell never feared actually having to pay damages to Corley; the issue here was collegiate recruiting. He intended to air the sorry mess in open court.

Corley filed a motion to quash the subpoena through his Houston lawyer, Hugh Hackney, a young partner at Fulbright & Jaworski who had received his undergraduate and law degrees from SMU. Hackney was also a member of the Mustang Club. Caldwell’s high-priced Houston lawyer was Joe Jamail, a prominent Longhorn booster and a close friend of Darrell Royal’s. Judge Gayle overruled Corley’s motion but disqualified himself from the case in mid-April. An energetic booster in his own right, Gayle had spoken more than a few words to the Stanley family on behalf of his alma mater, the University of Texas. The deposition thus wound up in the Houston court of Judge Wyatt Heard, a neutral but interested party. Heard frequently assisted the recruiters of his alma mater, Baylor.

Jamail spotted Corley coming toward Heard’s courtroom and interrupted Caldwell’s informal session with the reporters: “Counselor, my fee is a hundred thousand dollars an hour. Let’s get this show on the road.” Heard directed the principals, their lawyers, and a court reporter to a vacant jury room. The deposition lasted about twenty minutes before the judge called a recess pending Caldwell’s examination of Corley’s subpoenaed long distance records. Then Corley burst through the courtroom and shot down the hall, almost running toward the elevator.

As it happened, Corley’s phone records showed several Dallas-area calls during the peak recruiting weeks—including some to George Owen, a prominent Dallas booster previously noted for his recruitment of SMU stars Mike Ford and Eric Dickerson. Owen had been in Angleton trying to recruit David Stanley for SMU, and he was the Texas coaches’ prime suspect as the force behind the Lake Tahoe escapade. These developments were duly noted by the NCAA, whose Dan Beebe phoned Caldwell to request an interview and any other leads the judge might know of offhand. Caldwell couldn’t be certain that he had supplied the smoking gun, but he had pointed SMU’s pursuers down a tantalizing trail.

In the elevator that day, Jamail and Caldwell gazed upward with an air of supreme wit, as if they had just orchestrated an elaborate fraternity prank. Jamail was red-faced with suppressed laughter—veins stood out in his neck. Somebody asked the men how Corley behaved during the deposition. “I had the impression,” guffawed Jamail, “that he’d have rather had a boil on his ass than be in there!”

“Screw Them, Too”

From the Mustang Club perspective, the SMU football program was being whipsawed. The Times Herald found a Dallas Spruce running back, Robert Smith, who after signing with Iowa claimed that a Dallas municipal employee, Noel Brown, had given him small amounts of cash while recruiting for SMU. In Hawkins, near Tyler, another star running back was blowing the whistle. Edwin Simmons, who has the rangy build and slashing style of a Calvin Hill and advance billing as the next Earl Campbell, stood up SMU recruiters on his scheduled official visit and signed with Texas. SMU partisans accused UT alums of subjecting the Simmons family to intense and coercive pressure and of violating standards of common decency, if not NCAA rules. But Simmons told the Times Herald that SMU alums had made a standing cash offer. Simmons added that he had been cooperating with the NCAA, whose investigator stressed that the subject of his inquiry was SMU, not Texas.

SMU recruiters were bitter about another player they lost this year. They had a verbal commitment from James Lott, a Refugio receiver and defensive back who holds the national high school record—seven feet four inches—in the high jump. On signing day, February 9, Lott changed his mind and signed with Texas. SMU boosters accused UT recruiters of violating the visitation rules and making monetary overtures to both Lott and his grandmother, with whom he lived. But the Times Herald focused on a twenty-year-old uncle, Isaiah Lott, who lived in the same house and influenced his nephew more in the manner of a respected older brother. Jack Ryan, a Corpus Christi rancher, oilman, and member of SMU’s Mustang Club, hired Isaiah to maintain the grounds of his mansion starting February 11. Isaiah got to keep the needed job despite his nephew’s defection to Texas, which by standards in the business world would seem to exonerate Jack Ryan, but the job offer was an apparent violation of NCAA rules (though a drop in the bucket compared to the accusations lodged against Texas by SMU). In response to the stories about the booster and the uncle, NCAA investigator Dan Beebe added Refugio to his travel agenda.

With some acid comments about the NCAA, SMU recruiter Mike Barr resigned from the staff in June to enter the real estate business with Rick Fambro, a former SMU player, coach, and understudy of Sherwood Blount. As promised, the city and its favored school took care of their own. But in the view of some knowledgeable observers, Bobby Collins’ future as head coach at SMU may be hanging in the balance, pending the outcome of the NCAA’s investigation. “Our people in our department are very bitter,” SMU athletic director Bob Hitch told the Morning News on July 17. “We are having a tremendous morale problem.” Asked in the same interview if SMU might sue the NCAA, President Shields replied, “If I felt that justice were not adequately dealt with, yes.” Should the preliminary inquiry become a full-fledged formal investigation leading to another term of probation with sanctions—which most SMU partisans gloomily presume will happen—they don’t intend to go gentle into that untelevised night. The scope of the school’s own investigation, headed by lawyer John McElhaney and Bob Hitch, hasn’t been limited to recruiting practices at SMU. It has in fact taken on characteristics of a vindictive counterattack.

In SMU’s interrogation of Tony Sexton, the Rice coach who made the allegations about Marquis Pleasant, McElhaney asked pointed questions about Sexton’s alleged overtures to the recruit’s fiancée. The SMU investigation has reportedly ranged as far afield as Rice head coach Ray Alborn’s attempted recruitment of Oklahoma running back Marcus Dupree. Hard feelings abound, and the situation is getting uglier. “At the appropriate time,” promises President Shields, the results of the in-house investigation will be made available to the NCAA. Over the summer, reports spread that Texas, TCU, A&M, Tech, and Rice were also under preliminary investigation by the NCAA. Since the rumors seemed to originate in Dallas—and each of those schools was known to have contributed to the investigation of SMU—the talk probably represented the wishful thinking of SMU partisans. But particularly among SMU’s boosters, there’s no question of the prevailing outlook. If they go down, they intend to take the rest of the conference with them.

In a graceful Spanish colonial home outside Angleton, Neil Caldwell puttered around in a baggy shirt and old stained Levi’s while a stereo played the scratchy opera on his collector’s-item 78’s. “There’s an old saying in my profession,” he chuckled, extending his hand to a small red parrot in a cage. “To wit: ‘Country judges serve for life unless they’re caught in bed with a dead woman or a live man.’ The last thing I need is the kind of publicity and controversy that has come my way because of my involvement in the David Stanley affair. I do not need an opponent.”

The bird accepted the offer of another perch. Withdrawing his parrot from the cage, Caldwell stroked the feathers on its back. “I’ll admit to all sorts of things,” he continued, “but I ain’t exactly coming from the radical fringes of Burnt Orange boostership. The last time that Texas beat Alabama in the Cotton Bowl, I could be found fishing that day down at the creek. I genuinely like David’s parents. I feel for what they’ve been going through, and I’ll guarantee you, my motivations at the outset were strictly as a friend. But I have been known to become involved in moral crusades. And the question becomes, Does the kind of intercollegiate athletics that we have really belong in our system of education?” Another question, of course, was whether the judge would have been so exercised had the star hometown linebacker chosen to participate in intercollegiate athletics while attending the judge’s alma mater. “If Texas is cheating, then screw them, too,” Caldwell replied, rather hotly.

Gridiron Dreams

By the second week of September, the enforcement division must advise SMU on the status of the inquiry. All indications point to an intensified investigation; this story may unfold for another year or two.

The enforcement division’s assistant executive director is a drawling, articulate young lawyer named Bill Hunt. He is, ironically, an SMU law school alum. Hunt scoffs at the notion that the NCAA has concentrated all its energy on a witch-hunt inquisition of his alma mater. Like the organization’s other investigators, Hunt declines all comment on any ongoing investigation. Still, in the context of the NCAA’s enforcement priorities, he drops a hint that doesn’t bode well for Bobby Collins and SMU: “A lot depends on the circumstances of the particular case and whether or not the institution or the individual involved is a repeat offender.”

Hunt would be astounded by the suggestion that a jurist of Charles Alan Wright’s reputation would compromise his integrity in order to protect the football program of the University of Texas. The structure of the enforcement procedure, Hunt maintains, prevents any individual from exerting undue influence. As for the charge that the NCAA’s traditional powers wheel and deal free of scrutiny, Hunt points to the heavy sanctions recently levied against the University of Southern California. In fact, from the NCAA’s national perspective, the SMU and Southwest Conference controversy is a minor fuss, though noisier than most. The enforcement division has its hands full everywhere. Speaking for the infractions committee this past spring, Charles Alan Wright announced a stiff term of probation and sanctions for the University of Arizona; heated investigations of Florida and LSU are also under way. And in most of the country the problems are compounded by basketball recruiting.

“I realize that college athletics can be criticized,” says Hunt, “but it’s interesting to me, as a lawyer, that these member institutions have on a voluntary basis developed an enforcement program with very meaningful sanctions. In a penalty involving TV sanctions, it can cost the institution a million dollars, not to mention the severe damage to its reputation. Other than the criminal enforcement system, I question whether you can find another element of our society as devoted to policing itself. You sure don’t find a comparable effort in the fields of doctors’ malpractice, lawyers’ disbarment, or journalistic ethics. The NCAA’s membership has devised and maintained an effective selfpolicing structure. And if they chose, they could tear it all down tomorrow.”

So in the NCAA’s view, the system works. All that’s needed is a minor adjustment here and there. For instance, last January NCAA delegates passed a rule, effective August 1, that alums would no longer be allowed to participate in off-campus recruiting. Boosters can still write letters and make phone calls, but they can no longer recruit in the athletes’ homes, and they can talk to the prospects only during their official campus visit. In another rule change, football players will now have to designate the recipients of their complimentary tickets to the athletic department, which will handle the exchange. Bill Hunt thus hopes that the issues at work in the Southwest Conference controversy have been resolved.

But every administrative edict raises new questions of fairness and enforceability in the field. Can the alum whose godchild happens to grow into a blue-chip linebacker reasonably be expected never to mention the virtues of his alma mater? Old friendships are the exception, interprets the NCAA. Well, how old? From the standpoint of the football coaches, the NCAA’s enforcers are so obsessed with that kind of technical minutiae that they sometimes fail to notice the forest aflame. If officials like Hunt desire effective self-policing by collegiate recruiters in the field, they should make it substantially clearer that the NCAA perceives a large difference between an illegal seventh visit in the recruit’s home and a guaranteed salary of $2500 a semester. For in the Southwest Conference, the real issue is the ugly one of money.

A radical proposal, totally repugnant to the member institutions of the NCAA, is simply to certify the semipro status of college athletes and reward them with a standard wage. But that would only raise the ceiling of monetary abuse. Coaches are pushing a proposal to provide athletes with a modest amount of spending money during the school year. After all, there’s no stigma attached to the cash stipends that often come with academic fellowships. The NCAA counters that few academic fellowships add up to the $25,000 to $40,000 valuation of a four-year athletic scholarship. Football players have access to those high-paying summer jobs, and if that’s still not enough, they can take out loans like other needy students.

Some recruits simply have their hands out, and the situation becomes more insidious when the parents try to profit from their sons’ talent. Many coaches contend that if more players lost their scholarships as a result of NCAA sanctions, the message might begin to get across. Citing rules that can and do strip the players of their eligibility, the NCAA interprets that argument as an attempt to shift responsibility from adults to teenagers.

College administrators are reluctant to exclude boosters from the recruiting process completely. But the air of Halloween frivolity among the most avid boosters is the heart of the problem. As long as boosters maintain social access to the players—who can’t be expected to reside in compounds of barbed wire—the NCAA’s investigators are going to have a heavy case load. The rationale of these overzealous boosters, we’re told, is that they’re just so grateful to the alma mater, and they have to do something to pay the institution back. So in the course of raising all that money and writing $50,000 checks to endow one athletic scholarship, sometimes they get carried away. Bull. The spectacle of successful middle-aged men fawning over muscular boys is pervasive in college athletics. It’s comical and sad. Maybe it has to do with lost youth, with gridiron dreams that were never quite fulfilled. But the most obvious proposal for quelling recruiting abuses by alums will be the last one enacted: grow up.

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Football

- College Football

- Dallas