Phil Danaher has 490 wins to his name—the most of any Texas high school football coach ever. But when he thinks back on his nearly fifty years along the sidelines, two notable losses come to mind.

In 2016, his Calallen Wildcats played in the 5A Division II final at AT&T Stadium, but the team fell short in a chance for Danaher to claim his first state title. He believes the officials called the game poorly. “We have film on it,” he says. “I don’t even watch it anymore.”

Danaher doesn’t need to see a tape of the other game. The details are hard to forget. It was January 1984, the beginning of his time at Calallen, a school district encompassing the northwest side of Corpus Christi. When he walked into the high school weight room to introduce himself to the football players in January 1984, the team was coming off a 3–7 season. The previous head coach had been sacked, and Danaher was his replacement.

Out of nearly seventy applicants, the 35-year-old hadn’t been the obvious choice. He wasn’t an alum, nor was he well known around the district. But he had turned around two football programs—first in Dilley and then at Hamshire-Fannett, southwest of Beaumont.

“I firmly believe that Calallen is a sleeping giant,” Danaher told the players. “And we can win big here.”

Freshman Jeff Baxter was skeptical. The football team hadn’t made the playoffs since 1956. Calallen didn’t even have a stadium; the team played home games at the middle school. But as Baxter looked around, he saw upperclassmen nodding their heads. If they’re buying in, he thought, we might be okay.

They started boot camp and then two-a-day practices. Splinters sliced into their hands and thighs as they bear crawled over “pipes” that were actually misshapen, wooden telephone poles—thick on one end and skinny on the other.

Once the season began, the team tied its first game and won the next three. Things were starting to click. Then district play began, and Calallen faced Gregory-Portland, ranked second in the state.

Thus ends the Cinderella story. The Wildcats got stomped, 69–0, and every Monday after that, the team started practices with 69 push-ups. Down and up 41 times, then rest like they did at halftime, then 28 more.

“First season and I get beat 69 to nothin’,” Danaher remembers. “But it taught them. And the parents finally realized—I’m gonna teach these kids to fight for it.”

I’ve interviewed congressmen and criminals, but I was nervous when I visited Danaher at his house in Calallen in March. Even though I had known his name for decades, I’d never had a conversation with him. Calallen football was a powerhouse by the time I started elementary school in the early nineties. At the end of each season, my classmates and I were bused to the high school for an autograph party. Players and cheerleaders would sign our maroon T-shirts or the white miniature footballs they threw to fans at games. The community was all in.

The year after the Wildcats’ 69-point loss, Calallen made the postseason for the first time in 29 years. Now the team hasn’t missed the playoffs in 37 years—the longest active streak in Texas.

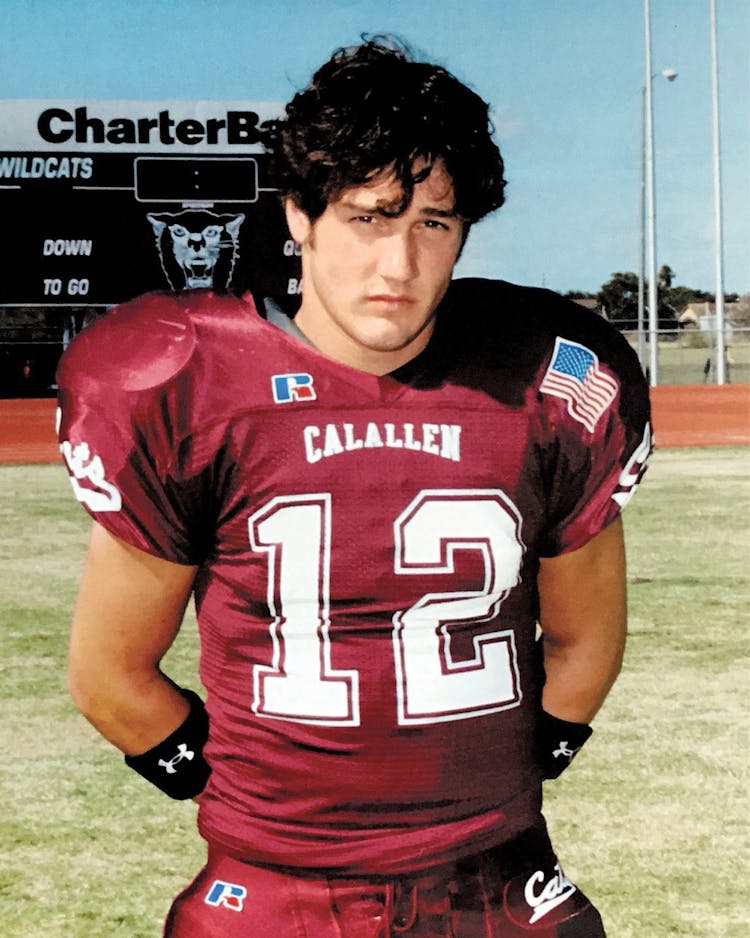

The records and accolades are numerous for Danaher. His overall record is 490–118. He’s had the most playoff appearances in the state. Most playoff wins, too. It’s no surprise he’s in the Texas High School Football Hall of Fame. He is a local legend whose lofty expectations and hard-nosed coaching measures have rubbed some parents the wrong way. Former players call Danaher “tough” and “ornery” but also credit him for having an impact that seeped in slowly and sometimes wasn’t felt until years later. Jonathan Vest, who graduated in 2005, didn’t play peewee football because Danaher told Vest’s dad to start him in the seventh grade. It would give Vest the best chance to prevent burnout and avoid being taught incorrect tactics at a young age, the coach said. When Vest made varsity at Calallen, he worked his tail off.

Vest played quarterback, but he wasn’t a star. A year ahead of him, another signal-caller was good enough to play at Texas A&M. And two years behind Vest, an exceptional, rising QB was waiting in the wings. Vest didn’t get the same attention from Danaher that others did. Still, every time he came home from college, he’d visit the Calallen field house to see his coaches. When Danaher heard his former second-stringer was playing college football at the Citadel, he expressed surprise that Vest made the team.

“Those words cut deep,” Vest says. “Some might read that as a negative thing, but for me, it gave me a reason to keep working harder and keep pushing myself because I had yet to impress this figure that I looked up to years before ever playing for him.”

When Vest stopped by the field house last fall, though, something felt off. Danaher seemed “rough mentally and physically,” Vest recalls. By then, rumors were already swirling around town. Danaher had missed the season opener. He would coach a few games and then be absent for the next. Was it COVID-related? Something else?

Danaher and his family had noticed it too. Now 73, the coach was no longer himself. He could remember details from when his children were young, but he struggled to recall recent events and simple contemporaneous facts like the day of the week. Since the summer before the 2021 season, he had been discussing his options with his family and school administrators. As his short-term memory faded, so did his future as a football coach. Danaher’s forty-eighth season coaching would be his last, he decided.

In their living room, Danaher’s wife, Anita, is quiet, but she looks me in the eye when she tells me bluntly, “He has dementia.”

At home, Danaher is surrounded by items that remind him of his storied career. The entertainment center is filled with football memorabilia. He shows me the gavel from the legislative session in 2017 when the Texas House of Representatives adopted a resolution praising Danaher for becoming the winningest high school football coach in state history. Next, it’s the two game balls from his son Cody’s days playing at the University of Texas: one from the Longhorns’ last game in the Southwestern Conference and another from UT’s first tilt in the Big 12. In a drawer, there’s a large red binder that Anita Danaher has put together. It contains newspaper clips and letters from other coaches congratulating Danaher on his record-setting 427th win.

He laughs as he remembers his time at Dilley, where he coached not only football but also tennis, basketball, and track. He recalls the day in 1974, just before he coached his first football game, when someone knocked on the locker-room door as he was hyping up his players with a pregame speech. The woman who’d interrupted his routine informed Danaher that there was a maintenance issue he needed to fix.

“I’m thinking, ‘I gotta get my team out on the football field, and you want me to change the lights in the girls’ bathroom?’ ” he says. In fact, that’s exactly what she wanted. “That’s what I ended up doing. And we ended up winning.”

When Danaher came to Calallen, football was his sole focus. Most folks in town only saw him on Friday nights, but he and his staff were working seven days a week, coming in after 2 p.m. on Sundays to allow for time with family and the Lord.

Their efforts paid off. In a 1985 playoff game, when the Wildcats came up against an opponent led by future Heisman Trophy winner Ty Detmer, the star quarterback broke a local passing record in a game against Calallen, but Danaher’s boys still walked off the field with the win.

“We stopped him,” Danaher says with a smile.

Calallen became a football powerhouse, and although it became the Wildcats who found themselves hanging 69 points on helpless defenses, Danaher refused to let his players gloat. At the 1995 state quarterfinals against Bastrop, Calallen’s players ended the first half by taunting the opposing team’s fans. In the locker room, Danaher coolly laid down the law.

“You are going to march your asses to their sideline and shake their hands,” Richard Wendland, a player on that team, recalls Danaher saying at halftime. “We are going to play the second half like gentlemen.”

It’s as if Danaher planted the seed of that 69–0 drubbing in 1984 under Calallen’s stadium (once it was built and the Wildcats could move out of the middle school facility) and used the searing pain of that defeat to inspire players through most of the next four decades.

“I didn’t really realize until probably my late twenties just how much I learned,” former player Jeff Baxter says. “Playing for him is very difficult. It made some of the stuff you deal with in the real world easier to handle because you’re like, ‘Man, I played for that guy in some of the toughest situations trying to build a program from nothing.’ ”

As football gained traction at Calallen, so did the dominance of other sports. Legendary coach Leta Andrews led the girls’ basketball team to a state championship in 1990. Girls’ cross country nabbed a state title the following year.

When I was a cheerleader at the school in the early aughts, we spent Mondays painting run-through signs and Fridays staging pep rallies. We put disposable cups in the chain-link fence that surrounded the stadium to spell out how far the football team had made it in the playoffs so drivers passing by would know if the Wildcats were in the district round or the regional finals or the state semis. And during the middle of the week, we were practicing for our own regional, state, and national competitions.

The baseball team won its first of three state championships in 2000, and its coach, Steve Chapman, became the winningest coach in Texas high school baseball this spring.

Yet despite two trips to the state championship game, Danaher and Calallen never finished a football season with the ultimate prize. That certainly wasn’t the plan, but falling short in a couple of individual, high-stakes games takes nothing away from the 37 seasons of excellence Danaher led his team through. “That’s one thing he did well,” Vest recalls. “He was looking at the big picture and building a dynasty, not just a better-than-average single year.”

These days, the cups on the fence have been permanently installed, and the stadium has been named after Danaher since 2009. The coach’s legacy in Corpus Christi is secure; he’ll be remembered for a long time.

Throughout our time together, I noticed small signs of his condition. He uses the words “booster club” when he means to say “boot camp.” He spends several seconds grasping for the word to describe the container where you throw your dirty laundry. Eventually, Anita reminds him: “Hamper.”

I ask how he feels to be finished with football after devoting so much of his life to the sport, but his reply doesn’t make sense. Danaher starts telling a story from a scrimmage more than thirty years ago, when he yelled at his son about a misread play. “Well, Cody learned to read it correctly,” he says. Again, Anita helps steer him back on track with the conversation.

I try rephrasing the question: “How is your life different, now that you’re not coaching?” All told, Danaher spent more than half a century on the football field. As a player, he dodged blocks and threw touchdowns at Harlingen High School, and as a coach, he paced the sidelines and preached discipline to decades’ worth of teenage boys. Now he sits motionless in his recliner as he mulls over my question. His answer, when it emerges, arrives as a whisper. I can’t hear it, so I lean forward and ask if he would repeat it. Danaher says just one word.

“Lonely.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Health

- High School Football

- Corpus Christi