A man in Abilene walks this morning, like every morning, down a bone-dry farm-to-market road outside town. He is out before the sun because he walks backward. That is to say, he walks in reverse, and he chooses this time of the day so he may behave in this odd fashion cloaked in darkness lest his neighbors see him and make him for crazy. His own mind is fairly certain on the point, but he’ll admit there is room for doubt.

He is not a brilliant man. Some would say he does not even encroach on smart. But inside his balding head he has a bold idea, and sometimes when a certain kind of man has a certain kind of idea, one that he considers good, that good idea crowds out all the other thoughts and ideas, and it becomes the only thing he thinks about. Such is the case with Plennie Lawrence Wingo, who is nearly penniless but full of ambition, just shy of his thirty-sixth birthday and a hair short of what would be one of the worst years in American history.

His garments show signs of a man who has put in a full day’s work by the time most are beginning to wipe sleep from their eyes, drag on their trousers, and start the percolator. He thinks about them, how they’d whisper if they ever caught sight of him out here, all alone and going backward. How they’d wonder what he was up to, what kind of crazy had gotten hold of him. They would, of course, ask him, “Why?” Over and over again, “Why are you doing this?” Even now, he is formulating his response.

He has not known a full day’s work in some time. They’d talk about that too, for sure. How his lot had soured. How they’d read about his troubles with the police in the paper. Another reason he is here, backpedaling in the dawn. He hoped they’d remember the good times too, when his future seemed full of promise. He was a man of business for a time, resourceful, straight as a preacher on Sunday.

His professional life in Abilene had begun six years before, in February 1924, at age 29, when he struck a lease deal with C. Hall for the north half of the lower story of the Morgan Jones building, at 127 Chestnut Street, in Abilene’s busiest district. He opened a restaurant, Crescent Cafe, soon after.

Then, in March of 1927, looking for a bigger slice, he signed a lease with C. C. Tate, renting the basement beneath Tate’s Dry Goods store on Lots 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, at the corner of Chestnut and South First streets, for a sum of $30 a month on the promise that Mr. Tate would build a staircase from the basement to the first floor so customers of P. L. Wingo’s Mobley Cafe and Dining Room could use the water closet.

He swept floors and bused tables and counted dollar bills. He served meat-and-threes to tenant farmers and ham and eggs to country lawyers and fried squash to the ladies from the Baptist church. Things were good for Plennie Wingo. Things were good for most everybody.

Following the miseries of the Great War, the United States experienced a time of prosperity unlike any the nation had known. It was a time of optimism and mass production and the mass production of optimism. Henry Ford turned out new cars every minute, and the nation’s first network of dealers rose up to sell them, followed quickly by a vast web of paved roads, traffic lights, hot dog stands, repair shops, and filling stations. Almost as quickly rose a nationwide network of antennae and broadcasting stations and hookups to pipe the phenomenon called radio into homes across America.

By 1925, American capitalism churned like a hungry machine. The number of manufacturing facilities in the United States had skyrocketed, and the worth of that output sprang up. In just five years, industrial production had nearly doubled. Men dumped their money into investments and reaped the profits hand over fist. Never before had so many become so stupendously, so painlessly, so expeditiously rich.

They were happy. They were credulous.

And there stood Plennie Wingo, a self-made man, at a time when the business of the American people was business, as the president said. It was an age of improvement, and Plennie was riding shotgun, all angular youth and bootstraps. He had a house in the city and a wife who loved him and a young daughter to whom he could one day leave his fortune. He leaned in the doorway of his cafe before the crowds trickled in, one hand in his pocket, a smile on his face, his necktie tight, shirt starched stiff, and his spit-shined wing tips planted firm on the ground.

That was then. Now he scoots in reverse. The sun creeps up and the shadows shrink as he wipes sweat from his face and picks up his pace. If he could walk backward through time itself, he would. He should’ve seen the signs. He should’ve known the men were coming for him, because they came for everybody.

They came on March 17, 1928, first to the dusty town of Pecos, 230 miles southwest. Fourteen strong-jawed lawmen and two federal prohibition officers seized 610 gallons of mash and whiskey and a 300-gallon still, then captured four ruffians on a ranch just over the New Mexico line and threw them in the Reeves County jail, charged with supplying a slew of nearby oil towns with strong drink.

They came again on April 7, 1928. Squint-eyed border patrol officers down south in desolate Del Rio confiscated 608 quarts of tequila and cognac in one of the largest liquor hauls anyone could remember. They came to the area time and again that year, doling out enough liquor charges to fill entire columns in the morning newspapers. They popped George Stringer of Abilene for transportation. Arrested Bud Moore of Abilene for possession. Collared Fred McCasland of Abilene for both.

The pace of takedowns was the talk of Abilene. In Texas, substantially more than half of all cases brought to court in 1928 revolved around booze.

Plennie Wingo should’ve seen them coming. The disappointment was fresh in his mind two years later, and when he closed his eyes he could still feel the click of the handcuffs around his wrists, the shame of his escort to the Taylor County lockup, the sting of the headline in the Abilene Morning Times: “Liquor Cases Are Pending Against P. L. Wingo Here.”

“Restaurateur P. L. Wingo, 33, was bound over Tuesday afternoon to await the action of the grand jury on a liquor complaint in which he is charged with selling and possessing intoxicating liquor.”

Thus he became one of the 55,729 liquor cases brought to court in the United States that year. The grand jury was cold, and the bond $750, more than two years’ rent on the cafe. It was terrible. Terrible, but not impossible to overcome. A black eye, but not a knockout for a man obliged to do better and better. With enough sweat and traffic, he’d be back in the black in six months, a year tops. People had money to spend, and Plennie was ready to trade them for fried chicken.

But then, in September of 1929, the market broke. The drop was short-lived, and by mid-month averages were back up. Then it slipped harder, and by early October most watchers knew something was wrong, though they weren’t sure what. Iron output was slower. Steel production was off. Fewer cars were selling and fewer were coming off the line. Home building was down. Freight-car loadings fell. Nonetheless, said the chairman of the National City Bank of New York, “The industrial situation of the United States is absolutely sound and our credit situation is in no way critical.”

What came next was monumentally bewildering and frightening to anyone paying attention. What came next, on the morning of Thursday, October 24, 1929, was liquidation. Prices dropped with an unprecedented and riveting violence. The market fell and fell until the news, slowly but surely, reached the rest of the puzzled nation around the time the market finally stopped its monthlong slide in the middle of November. The seams had come apart.

Before, the fundamentals were simple. A man needed to eat in order to work, and he worked in order to eat. But the house of cards had collapsed for reasons Plennie, like most of his fellow Americans, could not understand. What Plennie could understand was what he could see, that work was drying up in West Texas and with it, the sort of customers with money enough to afford a meal in a restaurant. Business was down. Way down.

Plennie tried advertising for $2.50 in the Abilene Morning Reporter-News and for less in the student newspapers at Abilene Christian College and McMurry College. But traffic slowed and bills came due, and he held on as long as he could. He scaled back by laying off employees, the hardest thing he’d ever had to do. And then the bank came to take the cafe for good.

But Plennie has a plan. His toes are pointed west in the new light as he reverses down First Street and rounds the bend onto Chestnut. If at first it was difficult to manage a mile or two backward without tiring, he can now finish ten without difficulty. He feels now, after months of training, as though he has been walking backward his entire life. He turns around as he nears his house, the sun higher now, the birds awake. He walks normal now, facing forward, up the sidewalk toward a home he stands to lose if nothing is done to make money, a home where his wife and daughter are sleeping, a home where the plan first struck him like a rattlesnake, seized him cold, and began to swell in his mind, his singular hope against hope: to gain fame and fortune by walking backward around the great world.

He would eventually tell his own origin story hundreds of times in hundreds of places, to anyone who cared to listen, until it became something like a hymn. He would skip the part about going to jail.

He was born on his mother’s twentieth birthday, January 24, 1895, the second son of John Newton Wingo and Willie Drucilla Warren Wingo, and his parents never would tell him or anybody else why they named their squirmy baby boy Plennie. John fell ill and was killed by pneumonia five and a half months after Plennie was born. Willie, originally from Union City, Tennessee, buried her young husband under a handsome column in the municipal cemetery in Abilene and, soon after, married his younger brother, Thomas. She would bear ten more children, one every two or three years for the next twenty years: Elias, Pearce, Lula Mae, Aubrey, Vera, Thomas, Bruce, Achel, Dee, and Lena.

Plennie was enterprising from the outset. When he was a boy, he learned to catch rattlesnakes, plentiful in West Texas. He’d use a long stick with a forked end to pin the rattler’s head down, then carefully grab the tail beneath the rattles and use the stick to guide the snake into an open burlap sack. They went for a few cents each, depending on the size, for meat or fashion, and the ones he caught weighed anywhere between two and six pounds. He sold them for spending money, and he was never afraid.

He started waiting tables as a teenager, working for a man named Jim Thurmond in a cafe when he wasn’t in school. He was a decent student, but he always had a restless and entrepreneurial spirit. “Mama,” he would tell his mother, “I want to go around this whole world.”

Plennie met and married Idella Richards, a hard-faced woman from Hays County, down around Austin, and she delivered their first and only child, Vivian, in 1915, when Plennie was nineteen years old. In the early twenties, a chunk of the Wingos—including Plennie, Idella, and Vivian—made their way northeast in a wagon brigade to Clay County, near Wichita Falls and the Oklahoma line. Within a few months, Plennie and Idella had opened a restaurant in nearby Dundee, which had been carved out of the T Fork Ranch and swelled in population after the Wichita Valley Railway Company ran a line through town and built a three-story hotel there as a stopping-point station. The town featured a school, a bank, and several businesses, and the population had grown to around 400. After a few years, the Wingos moved back to the boomtown of Abilene, which saw its population grow from 3,400 in 1900 to more than 23,000 in 1930.

Vivian was celebrating her fifteenth birthday with a party at their house when Plennie first bumped into his big idea. This was two and a half months after the stock market crashed, and Plennie had already begun to worry about his financial security. They’d had cake and opened gifts, and Vivian and her friends were talking and laughing together in the parlor. Plennie was reading the paper and minding his own business as the kids went on and on about how every physical feat had been accomplished . . . and wasn’t it true?

They wanted to see men and women dancing marathons and swimming the English Channel and walking upon the wings of airplanes. They wanted to be the first, the strongest, the best, the fastest—or at least to read about those who were.

If the boom years of the twenties had illustrated anything, it was that the country could be shaken coast to coast by a trifle, and there seemed to be something new every day. The nation’s newspapers often drew on syndicated wire services like the Associated Press and Newspaper Enterprise Association, so articles that might once have stayed local were now being read in papers across the country. On top of that, the sudden ubiquity of broadcast radio made it possible for more people to hear the same show at the same time. So the United States had become a nation of fad-loving gossips, prone to being swept up on waves of excitement generated by whatever was new or odd or dramatic.

In 1919, after the Great War—which lasted 1,563 days, destroyed empires, killed some 10 million soldiers, and cost more than $300 billion—more than 4 million Americans had participated in roughly 3,600 strikes over labor, communism, socialism, and anarchy. But a mere two years later, the Era of Wonderful Nonsense was in full swing, and with a chicken in the pot and a car in the garage, many Americans had withdrawn into an orgy of self-indulgence.

Americans wanted to read about the marriage of Hollywood starlet Gloria Swanson to the French aristocrat Henry de La Falaise, Marquis de La Coudraye. They wanted the details of the daily unfolding drama of Floyd Collins, a Kentucky explorer who got trapped in a cave. They wanted Jack Dempsey and Red Grange and Babe Ruth and Paavo “Flying Finn” Nurmi. They wanted Ripley’s Believe It or Not!, a cartoon panel of fascinating facts at the peak of its popularity, syndicated internationally and read by some 80 million people.

They wanted to see men and women dancing marathons and swimming the English Channel and walking upon the wings of airplanes. They wanted to be the first, the strongest, the best, the fastest—or at least to read about those who were.

They read daily about William Williams, a Texan who embarked in 1929 on an odd physical challenge in Colorado that exemplified the era. Zebulon Pike had first spotted what would become Pikes Peak in 1806 while exploring land acquired by the United States in the Louisiana Purchase. But his summit attempt was thwarted by waist-deep snow and insufficient supplies, and he concluded that “no human being could have ascended to its pinnacle.” Fourteen years later, an explorer named Edwin James reached the top of the 14,115-foot mountain. Then, in 1858, Julia Archibald Holmes became the first woman on record to ascend to the pinnacle. In 1901 two men from Denver drove a steam-powered car to the top. Then came Williams, at the end of the Incredible Era, a man of his time, pushing a peanut up the mountain with his nose. He blew through several pairs of shoes and gloves and more than a hundred peanuts, and he wore an advertisement for a Georgia peanut company. He finished in 21 days and offered the press a quote as odd as his stunt: “It doesn’t require pull for one to get ahead in life—it just takes push.”

The American people wanted entertainment. They wanted hullabaloo and ballyhoo. And, oh, how they wanted Charles Lindbergh.

The handsome young pilot wasn’t the first to cross the Atlantic by air, but he captured the country’s attention like no one else had or arguably ever would again. After a New York hotel owner offered up a prize of $25,000 for the first nonstop flight from there to Paris, nine men tried and failed to make the journey before Lindbergh climbed in the plane he had helped design for the transatlantic flight. On May 20, 1927, he turned himself into a legend. “Acclaimed by World as Greatest Hero in History of Aviation,” read the headlines in several Texas newspapers, which devoted hundreds of column inches to the airman.

Upon his return, the street cleaners in New York swept up 1,800 tons of scraps of paper that had been thrown out of windows onto Lindbergh’s homecoming parade through the streets. His reception, historians would note, took on aspects of a vast religious revival.

Plennie Wingo witnessed such a scene himself when Lindbergh came to West Texas in September of 1927, just four months after his epic flight. The Hilton Hotel hosted the Lindbergh Hop, featuring the Bob Dean orchestra. Downtown businesses competed for prize money by decorating Lindbergh-themed window displays with model airplanes suspended over construction-paper Atlantic Oceans and replica Eiffel Towers and Statues of Liberty. The event was so big that the Abilene Morning Reporter-News published its largest-ever paper, at 102 pages, heralding “Lindbergh Day” with a special section devoted to the colonel. The paper bragged that the newsprint used to print it, unspooled, would stretch all the way to San Antonio, 250 miles away.

Reporters estimated that all 30,000 Abilene residents, plus 40,000 out-of-towners, turned out to watch the dapper barnstormer ride in a 74-car parade from the airfield to downtown Abilene. Seated next to Lindbergh in an open-topped sedan was Mildred Paxton, the first lady of Texas and an Abilene girl herself, whose father ran Citizens Bank in town. Local contingents of the National Guard and the Boy Scouts saluted as the cavalcade traveled west to Oak, north to South Fourth, then on to Chestnut, gliding in all its glory right past the front door of Plennie Wingo’s cafe.

And seeing all that, bearing witness to the outpouring of pomp and solemn communal exaltation, changes a man, makes him want to be something more than he already is. How could it not?

A few months later, in January of 1928, a man named Henry “Dare Devil” Roland scaled the walls of the nine-story Mims Building and scattered the Abilene Morning Times from his perch as an advertising stunt. And then another “human fly,” by the name of A. L. Willoughby, climbed to the top of the Grace Hotel wearing a cape advertising a local business and dropped free pencils embossed with the business’s name to the crowd watching below. Not to be outdone, a third, Babe White, climbed the four stories of Abilene’s high-rise Hilton Hotel and hung from a ledge, dangling by a stylish silk dress that was for sale at nearby Minter’s.

The madness would not stop. In 1929 a man named Harm Bates Williams rolled a steel hoop 2,400 miles, from city hall in Texas City to New York City. Two apparently sane men, a tailor and a barber from Rule, Texas, announced plans to play a running game of croquet all the way to Manhattan; they were broke by Dallas. “We can’t eat croquet balls, you know?” one of the men told reporters. And a San Benito cowboy named Ralph Sanders began training a bull named Jerry, with plans to ride the beast from the Rio Grande all the way to New York. (Sanders and Jerry triumphed, traversing 2,700 miles of terrain over 254 days.)

“Has a wave of mild insanity swept over the American people,” asked the Shamrock Texan, “or are all these things merely the result of an inordinate craving for publicity?”

In July of 1929, a stuntman named Benny Fox perched for one hundred hours on a flagpole atop the Hilton, prompting a local woman, Pearl Pilkington, to write him a commemorative poem:

Stark against the lucid sky

You sit, an ominous bird, and survey the town,

Like a huge insect—a fly—

Impaled upon a pin

Under the shimmering waves of heat

You seem to float at noon;

Or drenched by the lurid sunset

Thankful for the coming gloom

Gloating, at midnight lone and black,

Jutted sharply

Between me and the puzzled moon,

Stubbornly you defy the hours,

Stringing them slowly, as beads upon a string,

Greedily—one by one.

A man reads something like that, sees how a show of endurance and good salesmanship makes people gush and practically hand over their money; well, it affects him, gets him to thinking. Makes him wonder if he might have a stunt or two up his own sleeve.

And when the stock market crashes in New York and the cash register falls silent in a cafe in Abilene and the owner begins to wonder how he’ll pay his bills and keep his family fed, thoughts that once seemed crazy don’t seem so crazy anymore.

And so at that birthday party the following year, as Vivian’s friends were in the parlor talking about how everything under the sun had been done and how there were no more stunts to pull, how a man had pushed a peanut up Pikes Peak with his nose and how a man had flown from New York to Paris alone and how you couldn’t even find an empty flagpole anymore, Plennie Wingo looked over the top of his newspaper and came right out and said something he could not put back in the bottle.

“Well,” he said. “Not everything has been done.”

Plennie Wingo had thought through the economics of his plan, but the math remained a little fuzzy.

“Is it so bad to appear foolish if you’re well paid for it?” Plennie said. “Suppose it pays off. Look at Lindbergh. Everybody called him crazy too.”

After the bank took the Mobley Cafe, Plennie took a job at the K. C. Waffle House, on Pine Street. He was working ten hours a day, seven days a week, and his take-home pay was a measly twelve bucks. Seventeen cents an hour. It was something, but he had to draw money from his savings every week to feed his family, maintain the house, and keep Vivian in school. And little by little, his stash dwindled away. But that’s what made the stunt seem even more appealing. If you’re working seventy hours a week for scraps, is it really that big a gamble to try to make money by walking backward around the world?

He had tried his best to sell Idella on the idea, backing into it gently at first, talking about folks like Benny Fox and Babe White. He’d show her articles in the newspaper and comment on how much money other people were making off stunts. He was so persistent that she cut him off one day.

“You’ve got something foolish on your mind,” she said. “If so, out with it.”

He felt the courage rise up into his throat. He spilled. “Is it so bad to appear foolish if you’re well paid for it?” he said. “Suppose it pays off. Look at Lindbergh. Everybody called him crazy too.”

He kept it up, trying to wear his practical wife down while he made preparations. He knew a chiropractic doctor, a Scotsman, who had advertised that he could train a human being to overcome any physical challenge whatsoever. Plennie walked to his office one morning, described his idea, and asked the doctor what he thought of it. “Mr. Wingo,” the doc said, “if you want to try it, I’ll be glad to give it some thought and work out some exercises to develop the muscles you’ll need.”

Part of Plennie had been hoping the good doctor would talk him out of it.

“But it will take work on your part to get ready,” the doctor said.

“Well, it won’t hurt to train, will it?” Plennie said. “Not at all,” the doctor said. “It will help you physically, even if you eventually give up the trip.” The doctor thought about it for a week, then devised an exercise routine that would work the set of leg muscles Plennie would need to walk twenty or thirty miles a day, backward. He gave Plennie the instructions, then insisted he would take no payment. He said he wanted to help prove that a human could do whatever he set his mind to. He said he’d be repaid with satisfaction when Plennie returned.

He also predicted a challenge Plennie hadn’t really thought about. So far, Plennie had been holding a mirror in his extended arm and using the reflection to guide his walking. Alas, that didn’t seem practical if Plennie intended to put in serious mileage or traverse highways, crowded city boulevards, stairs, hills, dales. Who knew how many mountain ranges there were out there? This posed a problem, both men agreed.

The answer appeared a few days later, almost like magic, in the back of a magazine. An advertisement featured a pair of sunglasses with small mirrors affixed to each side, meant for motorcyclists and sports car drivers for extra safety. Plennie couldn’t believe it, took it as a sign that this was meant to be. He pulled more money from his savings and sent it along with his order. When the glasses arrived, he’d been at his exercises for several weeks. He’d lost weight. Gained confidence. Felt great. He practiced by wearing the glasses around the house, then ventured out in the daylight, making sure he turned around and walked forward when a car passed so no one would think him a fool or try to steal his idea.

When the plan began to feel real, he started corresponding with shoe companies, but he didn’t let on in the letters what he planned to do, just that it would be big and would involve shoes and that they’d want a piece of it, definitely. He received several kind replies but no takers, not unless he’d tell them what he had in store. He kept the letters anyway, and waved them in front of a few close friends, passing them off as propositions for sponsorship contracts. He was surprised by how suddenly they went out of their way to do him favors.

He convinced one of them, a young friend who was about twenty, to join his endeavor and work as an advance publicity man. Basically, Plennie told him, your job will be to drive ahead to the next town of size, where you’ll contact the city officials, newspaper types, businesses that might need the advertising, and get them all interested and ready for Plennie L. Wingo, the Backward Walking Champion of the World. Whatever ventures you line up, Plennie said, we’ll split fifty-fifty. Sounded to the boy like a good deal.

The two hit up the Abilene chamber of commerce first, with a grand offer: Plennie would talk up the beautiful city of Abilene everywhere he went if the chamber would offer a purse at the end of the journey, some sizable amount of money that would make it all worthwhile. The chamber folks seemed deeply interested but admitted they were broke. The Depression had wiped out the budget for ambitious . . . world advertising. But, they said, try a larger city.

The next day, Plennie and his new partner climbed in the car and headed east 150 miles on State Highway 1 to Fort Worth. They tried the chamber of commerce first, but no luck. An official there directed the pair to the Southwestern Exposition and Fat Stock Show, which was opening in a few days. Plennie let his partner do the talking as he watched the faces of the stock-show men change from curious to jaded. Before they had a chance to say no thanks, Plennie jumped in and turned on his Texas charm.

“Sirs,” he said, “suppose we travel through towns within a hundred-mile radius of here, where I will get out at the city limits and walk into town backwards while my partner goes on ahead to publicize your show’s opening date?”

The president consulted with his men and came back with a question. Would they work for ten days, carrying signs advertising the stock show in towns like Plennie said, for $250?

Two hundred fifty dollars. It would’ve taken Plennie 21 weeks to earn that at the K. C. Waffle House. Yes, he said. And he signed a contract immediately.

He made his first nervous appearance on March 3, the same day President Herbert Hoover signed a law making “The Star-Spangled Banner” the official national anthem of the United States, and maybe that was fitting. Plennie wore cowboy clothes, cowboy boots, and a ten-gallon hat. He backed timidly at first, but his training took over, and before long, he was crossing busy streets and climbing easily over curbs. A crowd gathered to stare at the fella scooting around like an upright crawdad for no apparent reason. They had a thousand questions. Was it natural for him to walk backward? Where did he learn it? How long had he been practicing? What would he do when he got to the ocean?

The publicity man told the people to read about it in the papers the next day, and they did.

“Reverse Walker in Corsicana Tuesday Advertising Show,” read the headline in the Corsicana Daily Sun.

They drove across God’s country for the next six days, stopping in any town with enough people to form a crowd. Waco, Hillsboro, Burleson, Cleburne, Weatherford, Decatur, Denton. The newspapers in every city printed favorable stories, usually accompanied by photographs. Plennie spent the last three days of the contract walking around the showgrounds wearing the advertising and the silly cowboy getup.

The turnout for the show broke every record, and the officials were well pleased. Plennie was exhilarated. He had expected public reaction, but nothing on the level he’d witnessed. If only he had more money—or the promise of money—he could get started on his walk around the world.

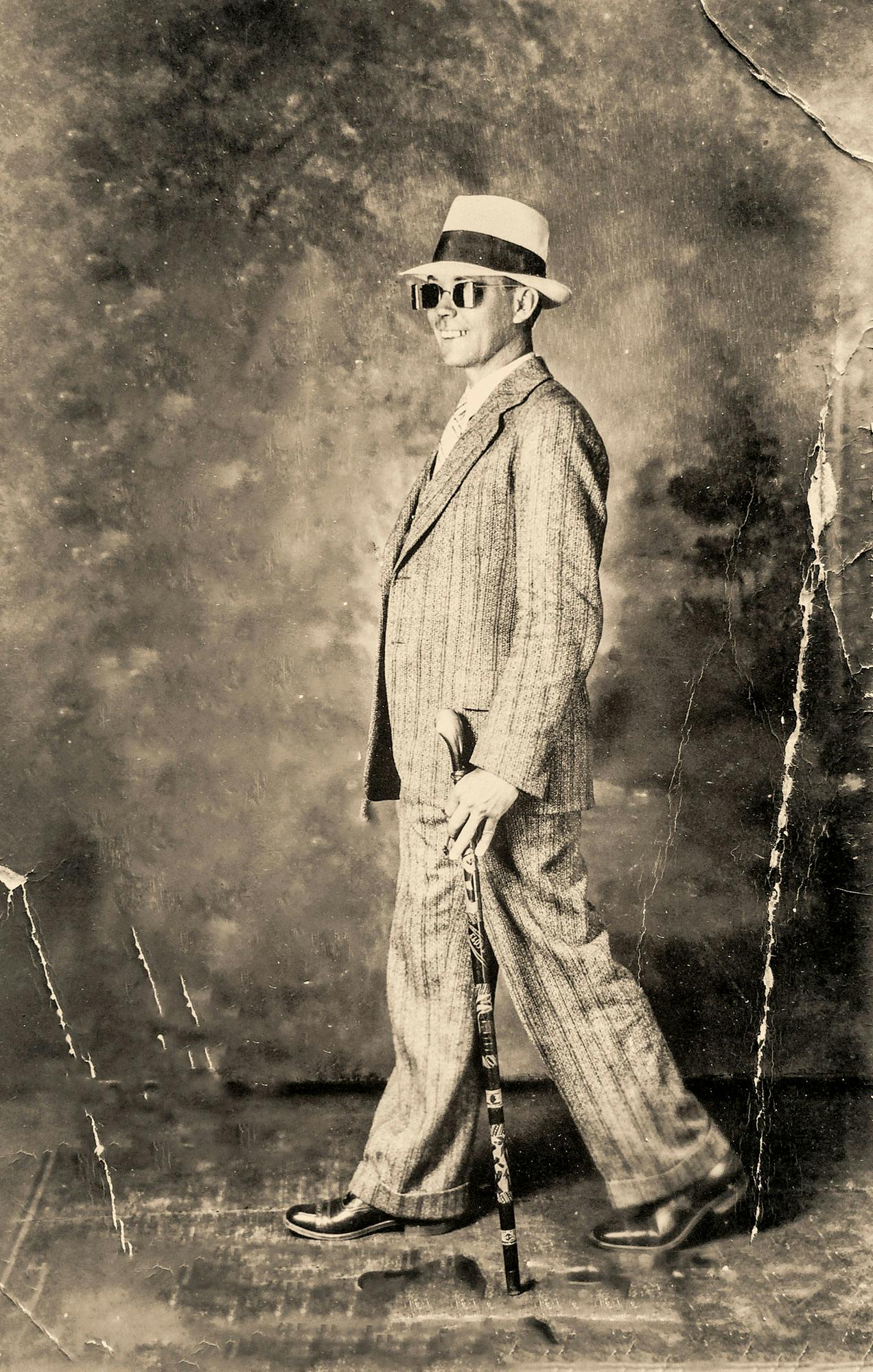

On April 15, 1931, the sun climbing up over Fort Worth, Plennie Wingo pulled on his best pair of pinstripe pants, one leg at a time. He buttoned his white Oxford over his lean frame, tied his necktie snug, slipped into his shiny black Sunday shoes, and slid into a suit coat that matched his trousers. Finally, he pulled a white Stetson Panama down on his ears, a good-guy hat for a guy trying.

If a man aimed to walk backward around the world, best to leave no doubt in the minds of passersby that he was doing so with purpose. Plennie Lawrence Wingo was a businessman on a business trip. The letters he carried on his person—official letters from Texas dignitaries—spoke to the serious nature of what might have been interpreted as an act of folly.

The day before, he had met once again with officials at the Fort Worth chamber of commerce, whom he tried to persuade yet again to fund his trip in exchange for advertising Fort Worth to the whole wide world. He didn’t have much money to begin with, but he told the businessmen he was going to wire all he had to his wife and start his trip without a penny in his pocket, just to prove he could.

“And I promise I will not beg, borrow, or steal,” he said. Barring sickness or accidents or objections, or maybe laws that would prohibit him from walking backward across certain states or countries, he was going to do it or die trying. “I firmly believe I can complete the tour around the world on my own and alone,” he said.

One of the men piped up. “Mr. Wingo, I admire your spunk,” he said. “I believe you will go far.” With that, Mr. Charles G. Cotten, manager of the trade extension department for the Fort Worth chamber of commerce, penned a letter and handed it to Plennie: “This will introduce Mr. Plennie L. Wingo of Abilene, Texas. Mr. Wingo begins a backward walking tour of the world from Fort Worth on Wednesday, April 15th. Upon his arrival at the various cities scheduled on his itinerary, he will report to the office of Western Union and it will be appreciated if you will be kind enough to indicate the time of arrival in your city and the time of departure with our thanks.”

It was tucked into the black notebook Plennie had bought from the variety store, along with a cheap fountain pen. He also carried a new Holy Bible, a gift from a street preacher named Paul Clifton, from the Open Bible Mission, whom he’d met the day before. Clifton had recognized Plennie from the newspapers and approached him on the street. “My prayer will be with you all the way,” he had said, and it had made Plennie wonder about things.

Now Plennie dragged his suitcase into the Greyhound bus station. He showed Mr. Cotten’s letter to the man behind the counter. The man looked Plennie over, then studied the letter, then agreed to carry Plennie’s luggage free of charge all the way to New York City, in the spirit of goodwill.

Plennie walked from the bus station to the Western Union and showed his letter to the clerk, A. C. Farmer, who, upon reading the letter, stamped it in the bottom left-hand corner: 9:03 a.m., April 15th, 1931.

“Which way are you going around the world?” Farmer asked.

“Going east,” Plennie said. “You keep watching west and I’ll be back.”

His friends had clustered outside. So had some strangers wondering what the commotion was about. Plennie greeted them all, shook their hands, and thanked them. He turned to face the west, waved, and took his first step backward.

And so it began, a man walking east toward Dallas, down Main Street to Highway 1, on his way somewhere, doing something. He watched automobiles appear like ants at the end of a long, unspooled ribbon of highway, the land as flat as a tabletop, and they grew larger as they drew closer, closer, closer . . . then zoomed by in a gust of dust. The dirt devils danced at his feet as he hugged the shoulder, as close to the edge of the road as possible, for 6,230 people had already been killed by automobiles in the first three months of 1931, an astonishing number of newfangled deaths. He nodded or waved or smiled as drivers and wives and backseated children bent their necks and puzzled over the odd man on the highway. And then they were gone, as quickly as they came. He was tickled by the looks on their faces. It was him they were trying to see.

One-hundred-twenty-three million Americans on the planet, and only one walking around it backward.

Plennie Wingo stood still in the hot lights, a curtain painted with a rural scene of tall trees and a winding river behind him, as the Dallas photographer made adjustments to his camera. Plennie assumed the posture of a man walking in reverse, though in the image that would be frozen in time, he could just as well have been walking forward, or sideways for that matter. His feet were inside shiny black shoes, and he wore a light patterned necktie and a dapper homespun suit one size too large for his small frame. His brown hair was neatly trimmed around his ears, and he wore on his face driving goggles with small, rectangular mirrors fixed to the rims. In his left hand he held an impressive carved coffeewood cane with a polished buffalo-horn handle. Missing from that hand was his wedding ring.

He stood just five feet five inches tall but wore the shifty smile of a man twice his size, revealing a gap near his upper left bicuspid, the tooth behind the canine. He had been professionally photographed once before, sometime around 1911, his sixteenth year, with eight siblings and his mother and stepfather, but he was grown and independent now, twenty years later. A man, alone in the big city of Dallas, making a go of it. If only his mother could see him now, see how he eased with confidence backward across the busy big-city boulevards, how he’d already made more than a regular week’s pay in just two days of walking backward.

He had expected trouble in Dallas and was apprehensive upon arrival. While advertising for the stock show, he had been hassled by the Dallas police, who informed him that the city had implemented an ordinance prohibiting the carrying of signs of any type. So he stopped at a filling station on the edge of town to phone the mayor. Plennie explained that a policeman had nearly arrested him the last time he passed through, just a few weeks ago.

“Yes, but what’s your problem now?” the mayor asked.

Plennie explained what he was doing and that he planned to walk through Dallas in reverse. “May I ask your permission to pass through your city like that?” he asked.

“Well,” the mayor said, “we don’t have laws against the way you walk.” But he hesitated when Plennie told him he might soon be carrying a sign that said something like “Around the world backwards.”

After some hemming and hawing, the mayor said, “Oh, well, you come on through. If any of the boys stop you, just refer them to me.”

“Thank you, Mr. Mayor,” Plennie said, “and look out, Dallas.”

A police officer seemed to be waiting for him when he reached the Trinity River, the Dallas skyline jutting into the air behind him. He thought the mayor had double-crossed him, but the cop was just as curious as everyone else. Plennie explained himself.

“Buddy,” the officer said, waving him through, “the town is yours.”

Before long, a crowd formed and began following Plennie through the streets, between the impressive high-rise buildings, toward the Western Union. Dallas had grown leaps and bounds, and construction remained strong even then. The year before, a wildcatter had struck oil about a hundred miles east, and the city fast became the hub for black-gold affairs across Texas and Oklahoma. While other industry failed, oil development remained strong. In the first few months of 1931, nearly thirty petroleum-related business ventures had sprung up in or moved to Dallas, and banks were providing loans to develop fields as far away as the Texas Panhandle and the Permian Basin, out west.

When Plennie emerged facing forward from the Western Union with his book stamped, the crowd began to boo. It took him a second to realize why. He explained that his stunt was to walk every step backward between cities, but once he got the stamp he could walk forward about town until he was ready to leave, whereupon he’d return to the Western Union and start again backward. Folks seemed to understand, and Plennie thanked them and checked into a nearby hotel, where he cleaned up a bit and set out to take care of a few chores. He met a man who agreed to paint a sign on a piece of sheet metal—“Around the world backwards”—for no cost. He gave an interview to a reporter for the Dallas Morning News, and a short item ran in the April 19 paper under the headline “Walk Around World Backwards Is Goal of Visitor From Abilene.”

Then he ducked into the first photo studio he saw, Hugh D. Tucker’s studio at 2012 ½ Elm Street. Plennie had had an idea a few weeks earlier, an idea that he was sure would help him turn his crazy scheme into a moneymaker: as he made his way across the world, he would sell postcards to the curious featuring an image of the Backward Walking Champion himself. He explained his needs to Tucker, who told Plennie that his rate was $20 for a thousand postcards, which sounded like a deal. But after paying for his hotel stay, Plennie didn’t have enough for a thousand. They hashed it out, decided that he’d pay for half now to take with him, then Tucker would ship the other half somewhere along his route and Plennie would pay cash on delivery. Deal.

This was something of an odyssey, like something out of mythology, and Plennie was, even then, beginning to think about turning his adventure into a clothbound book. If all went well, the postcards, which he decided to sell for 25 cents apiece, would support his day-to-day needs. But liquidating his epic journey by way of book sales could potentially make him a wealthy man for life. If he could accomplish the enormous task of walking backward around the world—no small feat!—he could certainly capture the experience with words. What was so hard about it? If Pearl S. Buck and Edna Ferber could do it, so could Plennie Wingo. And who wouldn’t want to read that? The audience had taken shape already, in the crowds of lookie-loos following him through the streets. They would turn out in North Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, all the way up to Boston, Massachusetts, and across the Atlantic in Europe. All he had to do was put the words on the page and persuade them to part with their money. And he’d only just begun.

When the flashbulb popped there in Tucker’s studio, freezing in sepia for all time a man on the front end of a very important thing, Plennie was smiling as if he could hear a cash register ringing.

From the book The Man Who Walked Backward by Ben Montgomery. Copyright © 2018 by Ben Montgomery. Reprinted by permission of Little, Brown and Company, New York, NY. All rights reserved.