Last November, while Internal Revenue Service officers in Austin made plans to auction off nearly everything he owned, Willie Nelson golfed in Hawaii. After flying to California to spend Christmas with relatives, Willie drove the long, leisurely road to Texas, stopping first to play poker with his pals in Hillsboro before arriving in Austin, where he jammed at the Broken Spoke, taped a television show with Jerry Jeff Walker, and got ready to shoot the TV movie Another Pair of Aces. With friends on the set he shared his favorite new joke: “What’s the difference between an IRS agent and a whore? A whore will quit f—ing you after you’re dead.” To folks in a hotel elevator who asked him for an autograph, Willie grinned and said, “Only if you don’t work for the IRS.” By the time he saw fit to saunter into the federal building on January 7 and meet his persecutors, anyone who didn’t write for the National Enquirer could see that Willie wasn’t going to commit suicide over this one.

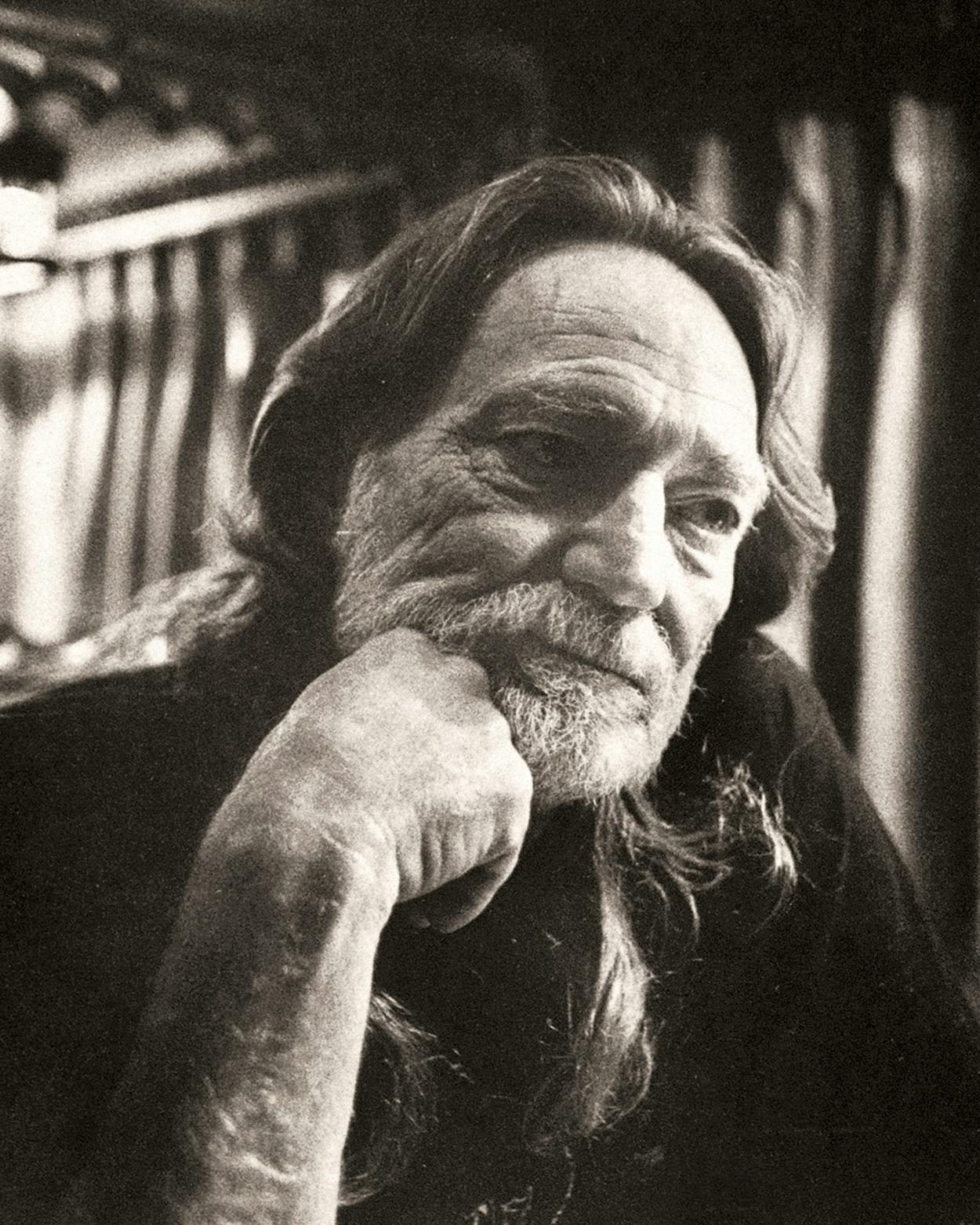

Aboard his touring bus, Honeysuckle Rose II, surrounded by a gaggle of followers, Willie spoke of his $16.7 million tax debt as if it were just another busted guitar string. He would fix the matter, he explained, with Who’ll Buy My Memories?: The IRS Tapes, a collection of old recordings that he intended to release and market through an 800-number promotion scheme. “I think that if we give it enough publicity, there’s no limit to what we could sell,” said Willie as his followers listened intently. “Within four or five months, the whole debt could be wiped out. We’d take a negative thing and turn it into a positive thing for everyone involved.”

It was a classic Willie Nelson brainstorm, elegant in its simplicity and so wonderfully expressive of the belief that to any question—including a financial question—music was the answer. It was also a foolish notion. Neither Willie nor his managers had bothered to figure out just how many copies he would have to sell to relieve his debt. Nor did anyone seem willing to ask whether Willie Nelson, in today’s market, could achieve such sales. When I later relayed the IRS Tapes plan to an old friend of Willie’s, he shook his head and said, “That’s just crazy. Even Michael Jackson in his heyday couldn’t raise that kind of profit.”

But no one on the bus voiced that sentiment. Willie’s followers merely sat there, saying nothing, adrift in their leader’s calm but compelling melody, and roused only when my questions suggested skepticism, at which times they would stare at me darkly. O ye of little faith, their scowls seemed to say, just as their awed reaction to Willie’s solution recalled all the old bumper sticker slogans: “In Willie We Trust,” “Where There’s a Willie There’s a Way.” Willie needed their faith now. For all his public buoyancy, privately Willie Hugh Nelson was an angry and worried man. Until he could satisfy his debt, his money and his property belonged to the IRS. The dozens who depended on him—including practically everyone in the bus that afternoon—were now out of work and stood to lose their homes as well. Willie had heard somewhere that an IRS agent had been assigned to sit on one musician’s tour bus and shadow his every movement. “I’m not about to let that happen,” he told a friend, but the prospect obviously unnerved him.

“As long as I’ve got my guitar, I’ll be fine,” Willie has often said, referring to Trigger, the legendary retooled Martin six-string he rescued from his burning Tennessee ranch house in the late sixties. Willie’s attachment to his old guitar was a bond that bordered on the spiritual. “When Trigger goes, I’ll quit,” he has been heard to say. But what if the feds came after Trigger? They had done it before, he’d read somewhere—taken an entertainer’s guitar and auctioned it off for $45,000. It was the one possibility that truly worried him. Two weeks before the IRS raid, Willie began to sense that negotiations with the agency were faltering. He asked the person he trusted most—his eldest daughter, Lana—to remove Trigger from the studio and personally deliver it to him in Hawaii. Lana did so, and Trigger was now in Willie’s hands—but for how long? Willie could manage without his recording studio, his golf course, and his Hill Country acreage. Without Trigger, all bets would be off.

How did Willie Nelson get into this mess? Three villains are commonly cited: the IRS; Neil Reshen, the manager during the mid-seventies who, according to Willie, left the Nelson organization in financial shambles; and Price-Waterhouse, the Big Six accounting firm that from 1980 through 1983 guided Willie’s money into several disastrous investments. All three have been sued or are currently being sued by Willie’s attorneys.

Amid the finger-pointing and the brief-filing, one curiously overlooked fact remains. Bad management and lousy investments notwithstanding, Willie Nelson had a golden opportunity to end the tax crisis several months ago, but he couldn’t pull it off. On June 6, 1990, Willie’s attorneys negotiated a settlement with the IRS. A tax order was signed that day, ordering the man with the greatest earning power of any country and western entertainer who has ever lived to come up with a mere $6 million.

But Willie couldn’t. He didn’t have six million. “He didn’t have one million,” said Lana Nelson. “He probably didn’t have thirty thousand.”

Short and wiry like her father but with her late mother’s dark Indian features, Lana has handled the family books for more than a decade. Stoically, she has done her father’s bidding, writing check after check, watching her inheritance dry up. And she has watched numerous financial managers try to halt the flow of reckless spending—to little effect. “Sometimes he’s his own worst enemy and simply will not take their financial advice,” said Lana.

The revelations of Willie’s daughter aren’t altogether shocking. After all, Willie Nelson’s whole life has been testimony to the belief that a man should live for the moment, take what comes, and never look back. Financial planning? Never. “It’s more fun if we don’t,” he has assured one of his attorneys. Money? Spend it now. And Willie spent and spent. But his is not the familiar story of the eighties, of greed that has backfired. It’s instead a story of generosity to a major fault.

Infidelity, a poor record as a father, an affection for outlaws, and an unrepentant fondness for marijuana—Willie Nelson has his vices. But they aren’t what did him in. Rather, Willie fell prey to his own loyalties, which became greater than his pocketbook could bear. “You can’t buy a ticket,” Willie would say, to the never-ending joyride aboard the Nelson bus. Familial devotion was the price of admission. But implicit was the understanding that the devotion would be rewarded. You could stay on the bus forever. Willie would pay for the gas.

And Willie paid and paid.

Tim O’Connor was working the cash register at his Austin nightclub, Castle Creek, twenty years ago, when Willie Nelson strolled in and invited the 27-year-old barroom brawler to join his extended family. The proposition actually began with “I’d like to play your joint,” but things got thick over a whiskey bottle. By the end of that evening, recalled O’Connor, “I already felt a deep sense of loyalty toward Willie.”

Loyalty was hard to come by in those days for Willie Nelson, who had just relocated to Austin after suffering a decade’s worth of disappointments in Nashville. He was a 38-year-old man on a downhill slope: a once-great songwriter who hadn’t penned a Top 10 single in ten years; a singer whose off-meter style rubbed his Nashville employers the wrong way (“That ain’t singin’,” they’d say, “that’s talkin’!”); a performer who lived a dissolute road life, while back home his marriages wasted away. The Abbott native was on his third marriage now, to the former Connie Koepke. They had a two-year-old daughter, plus children from Willie’s first marriage. Feeding all those mouths shouldn’t have been that difficult, since Willie continued to draw sizable royalty checks for such timeless classics as “Crazy” and “Hello Walls.” But he had fallen into the habit of immediately converting those earnings into hotel suites and booze and waking up the next morning broke again.

Willie was a lousy provider, much like his own parents, who had both left him before his third birthday to be raised by his paternal grandparents. Since those hard early days, he had never gotten a handle on the orthodox responsibilities of being a husband and father. But he deeply believed in trust and unconditional loyalty and yearned for others to have faith in those rare gifts. In that sense, Willie Nelson was a family man through and through.

Tim O’Connor learned this shortly after he had left his nightclub to join Willie’s road crew in 1971. One night O’Connor got frustrated with the unsteady routine of life on the road and demanded of his boss, “What the hell do you want me to be?”

Standing out in the rain, Willie Nelson told his newest roadie something he would always remember. “There’s three things I never want you to be. Cold, wet, and hungry.” O’Connor replied that he would thereafter follow Willie, into hell, if necessary.

Willie had never gotten a handle on the orthodox responsibilities of being a husband and father. But he deeply believed in trust and unconditional loyalty.

Hell is where Willie found most of his family. They were tough guys who had eaten their share of ground glass and seen both ends of a rifle—like drummer Paul English, who had made his cash off the whorehouse circuit in Fort Worth before joining Willie’s band; and promoter Larry Trader, who had been spilling whiskey with Willie since the early Nashville days. There was an indisputably wayward nature to these roadhouse warriors. It’s possible that they were unaware of how passionately they wished to believe in something until they found themselves believing passionately in Willie.

And so they slogged along together from one gig to the next, Willie and his Family, driving through the night until they ran out of gas, taking showers at truck stops, and enduring the cruel indifference of the road. Willie lived as the rest of them did, like peons. He wouldn’t forget the loyalty of men like Bo Franks, a radio ad salesman who quit his job to tour the country with Willie’s band and to sell Willie Nelson T-shirts out of his 1971 Malibu. “Several times throughout the seventies,” said Franks, “Willie had the opportunity to sell out my contract for hundreds of thousands of dollars. One fellow was particularly aggressive. Willie finally told him, ‘Where were you when we were sleeping in cars?’ ”

“Those were great times,” said Tim O’Connor, a sentiment echoed by Franks and other early cohorts. Willie’s Family was small then; the camaraderie was rich, their ambitions simple. The rewards, moreover, were slowly accumulating. In 1972 Willie ended his longtime association with RCA Records and signed with rhythm and blues producer Jerry Wexler and the new country division of the New York–based Atlantic label. His first Atlantic album, Shotgun Willie (which included the Nelson dance hall staple “Whiskey River,” written by Johnny Bush), was promoted aggressively and outsold all of his RCA records combined, but it still didn’t burn up the country charts. Willie’s next release, Phases and Stages, surpassed Shotgun Willie in sales.

The sound was catching on, and so was the persona. The man who once wore gaudy rhinestone-and-glitter Nudie suits as one of Ray Price’s Cherokee Cowboys and then took to wearing a poncho after seeing The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly now wore jeans and T-shirts and hair past his shoulders. While playing at Austin’s Armadillo World Headquarters in 1972, Willie squinted through the lights and saw more hippies than rednecks dancing to his music. A year later, he hosted his first Fourth of July Picnic, in Dripping Springs, and immediately became the patron saint of progressive country music. The succeeding picnics in College Station, Liberty Hill, and Gonzales were Woodstocklike affairs that drew upwards of 75,000 fans, as well as curious reporters from the national press. But Willie still wasn’t pulling in big bucks. Shortly after the first Picnic, he and Kris Kristofferson went for a drive. “I made a million bucks last year,” Kristofferson was grumbling, “and I paid three hundred thousand in taxes.” He turned to Willie. “You pay that much?”

Willie laughed. “When I make a million, I’ll let you know,” he answered.

By 1975 he was on his way. After Atlantic Records’ country division dissolved, Willie signed with CBS Records. With reluctance, the company released Red Headed Stranger, a concept album recorded in two days that featured a somber 1945 ballad by Fred Rose called “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.” The song rose to number one on the Billboard pop chart. That year Willie reported $581,000 in income. In 1978 Willie confounded CBS executives by recording Stardust, a collection of pop standards from the thirties and forties. Stardust went triple platinum, and Willie’s total earnings climbed to $2.1 million. All of a sudden he was the king of country, a Grammy perennial, and the highest-grossing concert act in America. For the first time in his life, Willie Nelson was making more money than he could possibly blow in one night.

Some of what followed Willie Nelson’s arrival is a story we’ve heard time and again, a story we’ve come to expect from entertainers who hit the big time. Property in the Texas Hill Country, Colorado, Utah, Hawaii, Alabama, and Tennessee. Expensive cars, a private jet. Movie and endorsement deals. Photo opportunities with everyone from Prince Charles to Andy Warhol. Rumors of infidelity, hanging out with the First Family, messed-up kids. Drugs. With an eye cocked toward the wretched excesses, we could imagine what would come next. We were fully prepared to believe the worst about this latest in a long line of heroes gone grotesque with glamour.

But instead, there were numerous stories of how Willie Nelson spread his newfound wealth, and most of them were true. Stories about the houses and cars he bought for his friends and family. About how he began letting each roadie get his own hotel room. About how he returned every favor “in spades, with interest,” said Bo Franks: a $38,000 bull for Faron Young to cover a $500 loan in 1961; a nightclub with Larry Butler, who loaned Willie $50 in 1958. About how Tim O’Connor once asked Willie to cosign a bank loan for $50,000—and then gasped as Willie returned from his bedroom with a $50,000 royalty check that he happened to have lying around and signed it over to his former roadie. About how Paul English, who had gone into hock for Willie and lost a wife to suicide just as the hard years were ending, became recognized by the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s highest-paid sideman drummer.

Though now making millions, Willie kept little of it for himself—perhaps only 10 percent of his annual income, according to Lana Nelson. His touring luggage was still a single small bag containing two pairs of jeans, a few T-shirts, and a shaving kit. It’s true that rich friends gave Willie a $15,000 Rolex and a $5,000 pair of cowboy boots. It’s also true that he gave the gifts away, along with practically everything else, prompting the popular refrain among his Family: “What can you give him for his birthday that he won’t give away?” His most valued gift, music, he gave away constantly, playing more than one hundred benefits over the past dozen years, according to Nelson’s management. A few of these events received media attention, such as the three Farm-Aid benefits staged in the mid-eighties to bring financial relief and public awareness to the nation’s imperiled small farmers. But the vast majority were staged quickly and quietly, and always because someone—a Phoenix Indian school, a Texas air base, a maximum-security prison-had asked, “Willie, could you play for us?”

As Willie’s generosity spread beyond the Family, so did the news of it. When crew members talk about the crush of Willie-seekers outside concert arenas, they don’t talk about people asking for autographs and sex. No, these total strangers wanted money—money for wheelchairs, iron lungs, funerals. Willie had a standard reply: “Will a personal check do?”

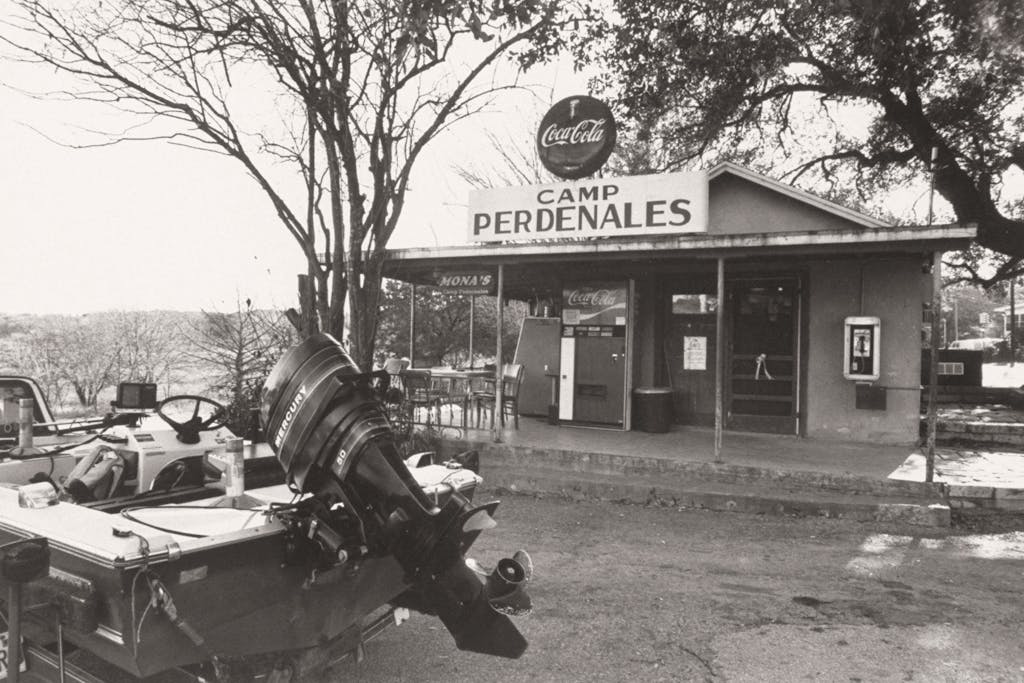

In 1979 Willie Nelson purchased the defunct Pedernales Country Club, a 76-acre expanse of rolling hills in the village of Briarcliff, near Lake Travis and across the road from the ranch, nearly 700 acres where Willie had his movie set and a 5,400-square-foot cabin built. He converted the clubhouse into the Pedernales Recording Studio and spent hours on the beautifully situated nine-hole golf course. But the Briarcliff spread wasn’t so much an indulgence of Willie’s as it was a haven for his loyal Family. There, everyone who had stuck by Willie during the hard days got a slice of the pie. Larry Trader became the club’s full-time golf pro. The other plum job, that of managing the new studio, was awarded to a short, straight-haired, waifish-looking young woman who had left her job in New York in the early seventies to follow the Willie entourage from gig to gig, helping out wherever help was needed. Her name was Jody Fischer.

Fischer’s real job was to oversee the paradise at Briarcliff—to allot free studio time for Willie’s music buddies, to see to it that guests were comfortable, and to assist Lana Nelson in fulfilling the various charity requests that crossed her desk. Willie paid Fischer a salary and provided a car and a house near the golf course. Fischer’s neighbors included stage manager Poodie Locke, tour bus driver Gator Moore, pilot Marty Morris, lighting director Buddy Prewitt, bodyguard Billy Cooper, Willie’s half-brother, Willie’s nephew, Larry Trader’s brother, and a few musicians who didn’t play in Willie’s band but whom Willie was fond of all the same. Near the country club, in a cabin situated in Willie’s Pedernales Fishing Camp, lived Ben Dorsey, a bent and bearded old fellow who claimed to have been John Wayne’s valet during the filming of The Alamo. Dorsey didn’t really have a job, but like Fischer and much of the rest of the entourage, he lived rent-free, courtesy of Willie.

For Willie’s Family, life wasn’t half bad. Every day was golfing day, the jamming at the studio lasted all night, and the bills went straight to the offices of Willie’s managers in Danbury, Connecticut. Fischer and Lana Nelson published a gossipy community newspaper, the Pedernales Poo-Poo. Up the road from the golf course, Willie built an $800,000 western movie set, where Red-Headed Stranger was filmed and where Willie’s cohorts frolicked. “We’d get drunk,” said Poodie Locke a little dreamily, “and we’d ride horses through there—like kids! It was a fantasy: wind’s blowing, a quart of tequila in you, the Texas sky. . . . How many people can play cowboys like that?”

Some of the people on Willie’s payroll were taking him for a ride—even some of the old loyalists, who now realized that they could chisel here and there and ol’ Willie would never notice.

By the end of the seventies, Willie Nelson’s camp began to resemble the coterie of a heavyweight boxer. Around the faithful nucleus grew layers and layers of business advisers and attorneys and court jesters and con artists. More than once Lana tried to tell her daddy that some of the people on his payroll were taking him for a ride—even some of the old loyalists, who now realized that they could chisel here and there and ol’ Willie would never notice. “His immediate reaction,” said Lana, “would be to turn around and give that person everything he asks for, just to prove me wrong, to prove he’s not making a mistake. And maybe I am wrong—or it appears I’m wrong. He doesn’t want to admit that someone has taken advantage of him, because it hurts his feelings, and he doesn’t want to deal with that hurt.”

Or perhaps, as Gator Moore suggested, “he doesn’t mind being conned.” No one could say for sure what Willie felt about these matters, and no one felt comfortable trying. This was one family that didn’t second-guess its patriarch. There were no doubters on the bus.

The fame, the fortune, the utopia on the Pedernales—all had come at a price years before. That price was Neil Reshen, a bullying new York entertainment manager who had secured Willie’s contract with Atlantic and, later, the seven-figure CBS/Lone Star Records contract that gave Willie full artistic control over his product and a custom label for his friends. Reshen’s clients included Miles Davis and Frank Zappa, fiercely independent talents whose quests for artistic freedom necessitated an equally fearless agent. Waylon Jennings, who first signed with Reshen in 1972, persuaded Willie the same day to sign on as well. In a 1975 interview, Jennings likened Reshen to “a mad dog on a leash.” Willie, in the same interview, said that Reshen was “probably the most hated and most effective manager that I know.”

With Reshen browbeating promoters and threatening to audit the record company, Willie and Family went places in a hurry. “Where we suddenly were was where we’d never been,” said Poodie Locke. “The most we’d made was a $5,000 New Year’s date. The next thing you know, it’s $10,000, then $25,000. Then we were going to Europe. I figured, ‘This guy’s taking care of us.’”

Someone had to mind the store, in any event, and it couldn’t be Willie. “I can’t be sure that taxes are paid and records are kept and also write songs and play music,” he said. “At some point you have to trust somebody. And that’s always dangerous.”

With Neil Reshen, it was disastrous. Jody Fischer, who was Reshen’s associate before leaving to become part of the Nelson entourage, said her former boss was someone who, “given the choice between telling the truth and telling a lie, even if the outcome was absolutely the same, would usually choose to tell a lie.” (“I absolutely deny that,” replied Reshen, “but I could be lying.”) In a 1980 suit, Willie said he was given the impression that Reshen was both a lawyer and a CPA, neither of which was true. What Reshen didn’t tell Willie was that he had pleaded guilty to embezzling stock from a Los Angeles bank. Nor, for that matter, did Reshen say that he wasn’t paying Willie’s taxes—Reshen’s responsibility, according to Willie, though Reshen has consistently denied this.

Willie had never been on the best of terms with the taxman. He had been hit for unpaid taxes for 1967, 1968, and 1969 and had been slapped with state and federal tax liens throughout the early seventies. Not that this was surprising at a time when, according to Tim O’Connor, “we collected the box office with a pistol and carried the dollars in a briefcase.” Back then, the road was meaner and the stakes smaller.

But now the numbers were very, very big. Of particular interest to the IRS were Willie’s Fourth of July Picnics, which drew tens of thousands of dollars in gate receipts. Perhaps, as Willie claimed, “that was when a lot of money changed hands. There weren’t the profits there that the IRS thought there were.” But the money had to have gone somewhere, and Willie couldn’t prove that it hadn’t gone to him. Besides, said IRS officers, showing Willie aerial photographs: There are 70,000 people here; why are there only 20,000 receipts? “They just weren’t aware of what really happens at those things,” said Willie, “where if you get one out of a hundred to pay, you’re fortunate.”

After becoming convinced that Reshen was damaging his reputation and siphoning off more than the agent’s share of the profits, Willie fired him in 1978 and promoted his assistant, Mark Rothbaum. Like Reshen, Rothbaum was a sharp, resourceful New York businessman. But more important, Willie felt he could trust Rothbaum, for he had proven his loyalty the hard way. On August 22, 1977, the police had intercepted a package containing several grams of cocaine, which was on its way to a Nashville studio where Waylon Jennings was recording. Mark Rothbaum pleaded guilty to distributing cocaine, did time in 1978, then went straight to work for Willie Nelson—“a sign of the faith and loyalty Willie felt for this man,” said Tim O’Connor.

In 1979, Rothbaum and Willie met with representatives of Price-Waterhouse, the internationally famous accounting firm. By then, it had been discovered that all of Willie’s financial records for the period of 1975 through 1978 had been destroyed. The IRS wanted $2 million for those tax years, and soon they would want more. The meeting therefore focused on a central subject: How do we keep Willie out of tax trouble?

After the meeting, Price-Waterhouse partner Herb Haschke wrote in a letter to Rothbaum: “One fact of business life which Willie cannot escape is that without tax-oriented investments, he will pay substantial amounts of income to the IRS every year.” In a 1990 lawsuit, Willie would claim that Haschke urged him to defer taxable income by investing in government securities issued by First Western Government Securities, a San Francisco–based firm.

Financial planning, of course, had no place in Willie’s worldview. His belief that you should spend your way through life and die a pauper kept him forever at odds with his moneymen. “Willie’s sense of responsibility about his wealth was not what I thought it should be,” said Harvey Corn, an Austin accountant who briefly did business with Willie after Reshen was fired. “I wasn’t at the time concerned with paying his tax bills. I was concerned, though, about the intelligent management of the considerable amount of money that he was making, with particularly his young daughters in mind. The fact is that Willie just didn’t see the world that way. He wasn’t worried about providing $20 million trust funds for his kids. You just couldn’t get his attention. You’d be talking to him, and then he’d just drift off and start picking on a song. You got the message after a while.”

The Reshen-era skirmish with the IRS persuaded Willie that he would have to modify his thinking somewhat. But the Price-Waterhouse proposal seemed a little dubious to him—especially because he would have to borrow money from a bank to invest in First Western. If he was going to borrow, why not just use the money to pay his $2 million in back taxes? “I couldn’t see it at the time,” said Willie, “and I argued with the professionals around me that this is not making sense.”

Nonetheless, on December 22, 1980, Willie invested $30,00 in a margin account portfolio of First Western forward contracts. The next year, Willie’s suit alleged, Haschke recommended in a letter that Willie make an additional investment to shelter his income despite the fact that Price-Waterhouse had learned that other First Western investors had been questioned by the IRS in 1981. Willie put in another $165,000, and Rothbaum himself invested a total of $43,440.

Later, Jan Smith, one of the Price-Waterhouse representatives who handled Willie’s account, admitted, “There’s a lot about First Western that’s known that wasn’t known in 1980.” The suit alleged that in telephone conversations in August and September of 1980, Price-Waterhouse partner John Walsh assured one of Willie’s lawyers that he had personally visited First Western’s operations in San Francisco and found them legitimate. Yet by 1983, the IRS began a serious probe of First Western, especially its practice of determining margins on the basis of the tax loss requested.

Recognizing that, Haschke suggested that Willie and Rothbaum abandon First Western and consider investing in cattle and cattle feed. The plan was simple: Buy cattle and feed at the end of the tax year, deduct the cost of the feed, and then sell the fattened cattle for a profit that would cover the cost of both the livestock and the feed. And, said Haschke, the plan was risk-free, since Willie and Rothbaum could hedge against a drop in cattle prices by selling cattle futures.

It sounded too good to be true—and it was. The bottom fell out of the cattle market in 1984, and Willie and Rothbaum lost $2 million between them. They later alleged in the suit that Haschke did not advise them to sell futures—that while cattle prices plummeted, Haschke couldn’t be reached. To make matters even worse, the IRS ultimately disallowed Willie’s $3 million deduction for cattle feed on the grounds that only $64,000 of the feed was actually consumed in 1983.

Things continued to get worse for Willie. On October 15, 1984, an IRS Notice of Deficiency was issued to Willie and Connie Nelson and to the Willie Nelson Music company in the amount of $2.2 million. The notice said that Willie still owed money from the Reshen years: more than $25,000 for royalties, some $360,000 in income, and $720,000 to cover business expenses that had been disallowed. Willie’s attorneys contested the matter in tax court, to no avail.

On May 20, 1988, Willie received a second Notice of Deficiency, this time for the years 1980 through 1982. Because of the disallowed tax shelters, he now owed more than $1.5 million for each of those years, plus millions more in interest and penalties. The mess had started during the Neil Reshen years, but the advice of Price-Waterhouse had led Willie Hugh Nelson to the edge of financial ruin. He sought the counsel of Jay Goldberg, a New York attorney whose clients included Donald Trump and the late Armand Hammer. Goldberg saw his chance to help Willie in 1990, when the U.S. Tax Court held that First Western Government Securities had engaged in fraud by creating tax deductions without regard to the possibilities of profit—a scheme, the court held, that “no reasonable person would have expected . . . to work.” On August 15, 1990, Willie’s lawyers filed a RICO lawsuit against Price-Waterhouse.

But it came too late for Willie. The IRS was quickly closing in.

It’s true that the IRS was legally empowered to seize the properties of Willie Nelson. It’s equally true that the action was drastic, a show of force that garnered enormous publicity, capturing the attention of middle Americans who might feel the urge to fudge on their taxes now and again. Perhaps the IRS was making an example of Willie Nelson. Had that crossed Willie’s mind?

“Sure it has,” he said, grinning. “But I have no facts.”

To hear Willie’s Family tell it, the seizure was a full-blown federal conspiracy. The feds regarded Willie as an outlaw, they say, a pot-smoking liberal whose Farm-Aid benefits embarrassed the government into canceling scheduled aid cutbacks. Only a few weeks before the seizure, Willie was in Kentucky, driving a bus with the word “Hempmobile” painted on it, in support of a fringe gubernatorial candidate who advocated the legalization of marijuana. That broke the camel’s back, say the loyalists. The last flaunting of Willie Nelson’s reckless spirit persuaded the feds to break Willie, once and for all.

But there is a far less hysterical explanation for the seizure of Willie’s property: The IRS took action not out of malice but because it had little choice.

By the spring of 1990, according to attorney Jay Goldberg, Willie’s tax tab had escalated to $32 million. When Goldberg successfully negotiated that sum down to $6 million in taxes, plus $9 million in interest and penalties to be held in abeyance, the message from the IRS was clear: Willie had to ante up a significant sum, say, $2 million, by September 6, ninety days after the June 6 tax order.

After electing not to pursue bankruptcy, the Nelson organization began to scurry around for cash. It was like chasing leaves in a hurricane, for Willie’s money flew in all directions. He continued to support his adult children from his first marriage (Lana, Billy, and Susan), plus two daughters from his marriage to Connie, who was now divorcing him—an endeavor that carried heavy financial overtones. In the meantime, Willie had a new girlfriend, Annie D’Angelo, and had fathered two children by her. Then there was the extended Family, itself multiplying daily.

As Willie’s beneficiaries had proliferated, the entertainer’s earning power had declined steadily. According to Pollstar, a concert industry publication, Willie was the seventh-highest-grossing touring act in 1985, taking in $14.5 million. In 1986, he was twenty-second, at $10.1 million; in 1987, twenty-seventh, at $7.7 million; and in 1989, forty-sixth, at $4.7 million. Excluding his performances with Highwayman (also featuring Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, and Johnny Cash), Willie’s concert earnings last year sank to a mere $3.3 million. And those were gross earnings, not net. “He had more expenses going out than he had concerts coming in,” confirmed Lana Nelson. “We’ve been living hand-to-mouth for the last couple of years.”

Record sales were equally discouraging. Since “Always on My Mind” had topped the charts in 1982, the old Nashville renegade had been supplanted by sexier turks like Dwight Yoakum, George Strait, and Randy Travis. His annual artist royalties hovered in the $300,000-to-$400,000 range—a fine income for anyone not supporting an entire community. In the meantime, Willie owed CBS Records more than $3 million in recoupable advances.

In August 1990, at the behest of his advisers, Willie Nelson sold his publishing company, Willie Nelson Music. All of his songs and the royalties they earned now belong to a company called Fuji Pacific. The notion of selling one’s music catalog in order to pay the taxman would horrify most songwriters. But the financial security that steady royalty checks had brought meant nothing to Willie, and he had already proved that he could live with himself after selling his hits for dirt. After all, he had pawned off two of his earliest classics, “Night Life” and “Family Bible,” for $150 and $50, respectively, in the fifties.

Willie Nelson Music had been earning about $225,000 annually in publishing royalties. Willie’s financial managers were therefore pleased with the Fuji Pacific offer, which totaled $2.27 million. Such a sum might have satisfied the IRS for a time. Unfortunately, $480,000 of the deal went to the tax agency to satisfy an entirely different tax claim concerning Willie Nelson Music. About $1.2 million went to pay off Nashville bank loans for which the publishing company had served as collateral. Another $360,000 went to Paul English, who owned 20 percent of Willie Nelson Music. At the end of it all, after the pot was split and all dealmakers were paid, Willie Nelson had sold off his birthright for a negative $35,000.

In the meantime, the IRS deadline of September 6 came and went. Admitted Jay Goldberg: “There were no substantial payments made.”

Many offered to help. Tim O’Connor suggested a Fourth of July fundraiser, but Willie—a man used to giving but never to receiving—quietly discouraged the idea. Others didn’t ask permission to declare themselves Willie benefactors. James White hosted a Willie-Aid benefit at his Broken Spoke in Austin, promising “very special surprise guests” and not volunteering the information that Willie had nothing to do with the concert—he was holed up in Hawaii and would not be among the night’s surprises. A West Lake Hills barber named Jim Hataway took it upon himself to establish a bank account for those who wished to contribute to Willie’s tax fund. Hataway didn’t know Willie, but he had shaken his hand once and was willing to talk at length to any reporter about the kind of guy Willie Nelson was. Sincerely intended or not, the effect of such schemes was to confuse rather than inspire the public. Was Willie behind all this? Was he trying to get fans to pay his taxes for him? In the end, IRS Tapes may not make a dent in his tax debt, and in the end, Willie may not care. “Willie just didn’t want to be the object of any charity,” said Larry Goldfein, Willie’s current financial adviser, and if nothing else, the recording proves that sentiment.

For now, the spread is safe. The IRS placed the Briarcliff property on the auction block at the end of January, but aside from the sale of a few souvenirs, no one had offered the minimum bid. Meanwhile, an Arkansas attorney representing several foreclosed farmers bought Willie’s ranch house, where Lana resides, and pledged to return it to the Nelson family. On March 5, former University of Texas football coach and longtime Willie crony Darrell Royal purchased the Pedernales Recording Studio, the country club, and the pro shop for a total price of $117,375 (its appraised value was more than $1 million). Royal didn’t say what he would do with all the property, nor did he have to. Willie had told me during our conversation on the bus, “I have friends who’ve offered to buy the property for me and save it until I can afford to get it back from them. I was assured of all that months ago.”

In the first week of April, Goldfein (an adjunct professor of tax law at New York University and an ex–IRS attorney) persuaded the IRS to cut Willie some slack. Under this new agreement, 75 percent of the net earnings from IRS Tapes will be earmarked for tax repayment, with the other 25 percent to cover Willie’s legal fees for the Price-Waterhouse lawsuit. Willie will be allowed, according to Goldfein, “a very liberal sharing of the proceeds” earned on the road. The full band will be able to tour, and the IRS won’t send an agent along to tour with them. The show will go on. But the IRS will receive a full account, every month, of how the money is being parceled out. That means the party’s over.

A few, though not all, of Willie’s Family members have started to get this message. “I’m pretty frustrated personally by the outer layers of bark and moss that have grown around Willie’s tree,” said Tim O’Connor. “And I think it’s burdened the tree. As far as I’m concerned, this is a great shakedown. Everybody should give the man some room to breathe for once.”

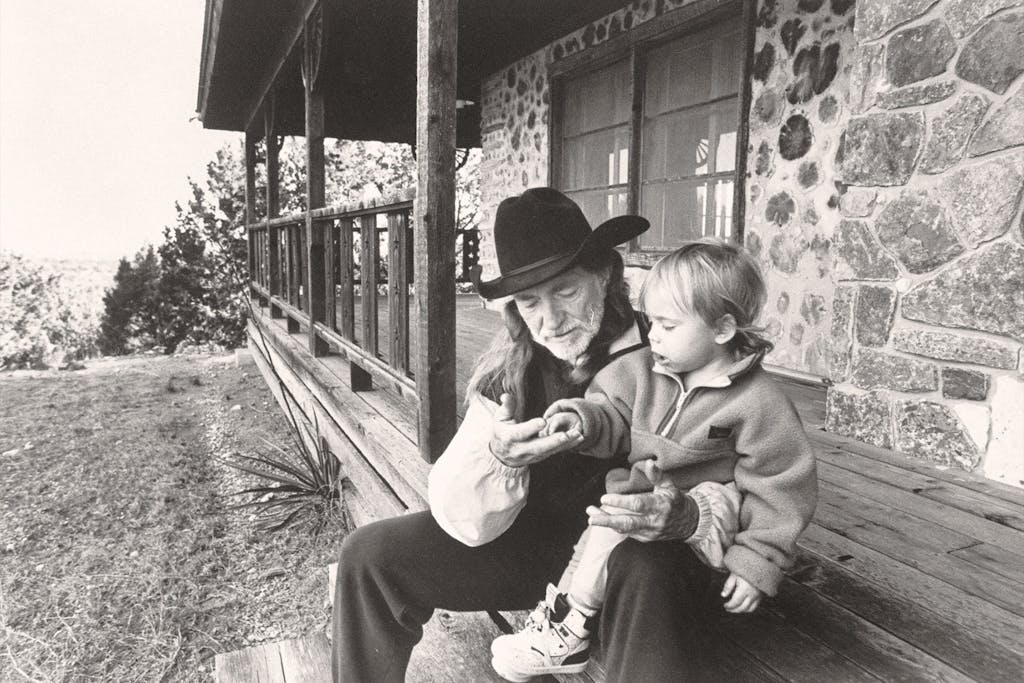

They talk about that over in Briarcliff—about the changes: a smaller roster, maybe a few old hands cut loose, or maybe the whole Willie community gradually disintegrating. “This is a test for everyone involved to see how we can react to a crisis,” said Lana Nelson. “As for me, this isn’t the brokest I’ve been. I remember as a child how I’d sit in the middle of a room and watch my mother and my daddy packing things with the midnight moving company. We’d move every month, when the rent came due.

“As for Daddy—what’s wrong with him just going on the road with his guitar? You know, he hasn’t cleaned house in seven years or so. And one thing he talks about is that everything happens for the best, no matter what. If he listens to himself, then maybe the positive side he’ll see is: ‘I won’t have all this responsibility to keep all these people on my payroll.’

“Then he can start small again.” Lana laughed, just slightly exasperated. “And it’ll take him another twenty years to build it all up again. See, he’ll be the same. He’ll still be generous. He’ll still want to give more than he actually has.”

Jody Fischer still aches inside with the memory of the day the IRS came to find out just what Willie had. “Where’s the fleet of cars?” the agents demanded of her last November. “Where’s the vault?” From behind her desk, the small dark-haired woman with the plaintive face could only gape. They weren’t making sense. This had to be some other Willie Nelson.

“We know all about Willie Nelson,” one of them had told her, waving a stack of government documents for effect. What Jody Fischer wanted to say in response was what anyone—not just those in Willie’s Family, but anyone with ears—would say: that any man who makes Willie Nelson’s kind of music will never be remembered for his tax liabilities. But the words just wouldn’t leave her heart. Faith can be such a clumsy language.

- More About:

- Music

- Music Business

- Longreads

- Willie Nelson

- Austin