Austin-based photographer Randal Ford started the sessions for his latest portrait collection as he always does. He spent a few minutes getting to know his subjects, made sure they were comfortable, and ensured that there were snacks on hand: some marshmallows, a pawful of nuts, maybe a raw chicken carcass.

The focus of Ford’s most recent body of work, after all, wasn’t on humans. For The Animal Kingdom: A Collection of Portraits (Rizzoli), the photographer—who has shot more than twenty covers for Texas Monthly—created portraits of over a hundred different beasts and critters, from horny toads to Longhorns. But these aren’t typical National Geographic–style images. “I wanted to use my lighting in studio to create a certain polish and beautiful aesthetic that you can’t do when photographing an animal in the wild,” Ford says. The resulting likenesses are vivid and strikingly personal, as if the animals are introducing themselves.

A decade ago, Ford found himself taking photos of cows in studio for the magazine Dairy Today. “These pictures really became portraits of the cows, showing their personality and coming to life, in a way,” he says. “I figured that if I could show the personality of a cow, I could also do it with other animals.” Then, in 2014, Ford photographed some dogs and cats for an advertising campaign.

Soon after, Ford decided to go for what he referred to as the “Wizard of Oz trifecta,” and an animal trainer in L.A. introduced him to a lion, a tiger, and a bear. “The experience of standing four feet in front of a big cat is truly tangible,” says Ford. “You could feel their power and their magnificence and their grace. It was just unbelievable.”

He had caught the bug. Over the next four years, Ford traveled across the country, gradually ticking off animals from his dream shot list. There was Yohan, a cheetah who lives at a wildlife sanctuary outside Dunlap, California; Walter, a great horned owl and a resident of Auburn University’s Southeastern Raptor Center; and Perry, a two-toed sloth who hangs with his owner in Mineola, Texas. Sadly, a polar bear and a roadrunner were out of reach.

The project led him to a community of primate handlers, an armadillo racer, and folks devoted to unusual creatures. Often, Ford’s growing network of animal lovers would help him track down an elusive subject: the owner of a Longhorn knew someone with a white buffalo; a dog trainer led him to a black goat. Sometimes, those cross-species introductions happened under the same roof. “A lady in North Texas had rescued a baby skunk and removed the skunk glands,” he says. “All of a sudden, she had a pet skunk in addition to her pet squirrel.” (According to Ford, Bandit the skunk and Merle the squirrel get along just fine.)

Along the way, Ford began to master the skills necessary to handle nonhumans in the studio. “It’s almost like photographing kids,” says Ford, who learned to snap photos quickly, before animals got bored and fidgety. “You’ve got to be hyper-focused. They may just give you one look, and that’s the best shot.”

When Ford photographed Dexter, a mountain lion who works in L.A., trainers kept the big cat attentive by feeding him raw chicken on a stick. Dexter swiped at a piece with his paw, knocked it off, and jumped from his perch to retrieve his meat where it had landed—mere inches from Ford’s sneakered feet. “The fear inside me was literally like a rushing wave drowning me. But I knew damn well not to move,” Ford wrote in the book. The feline reclaimed his treat and ambled back to the platform. Ford decided he was done shooting for the day.

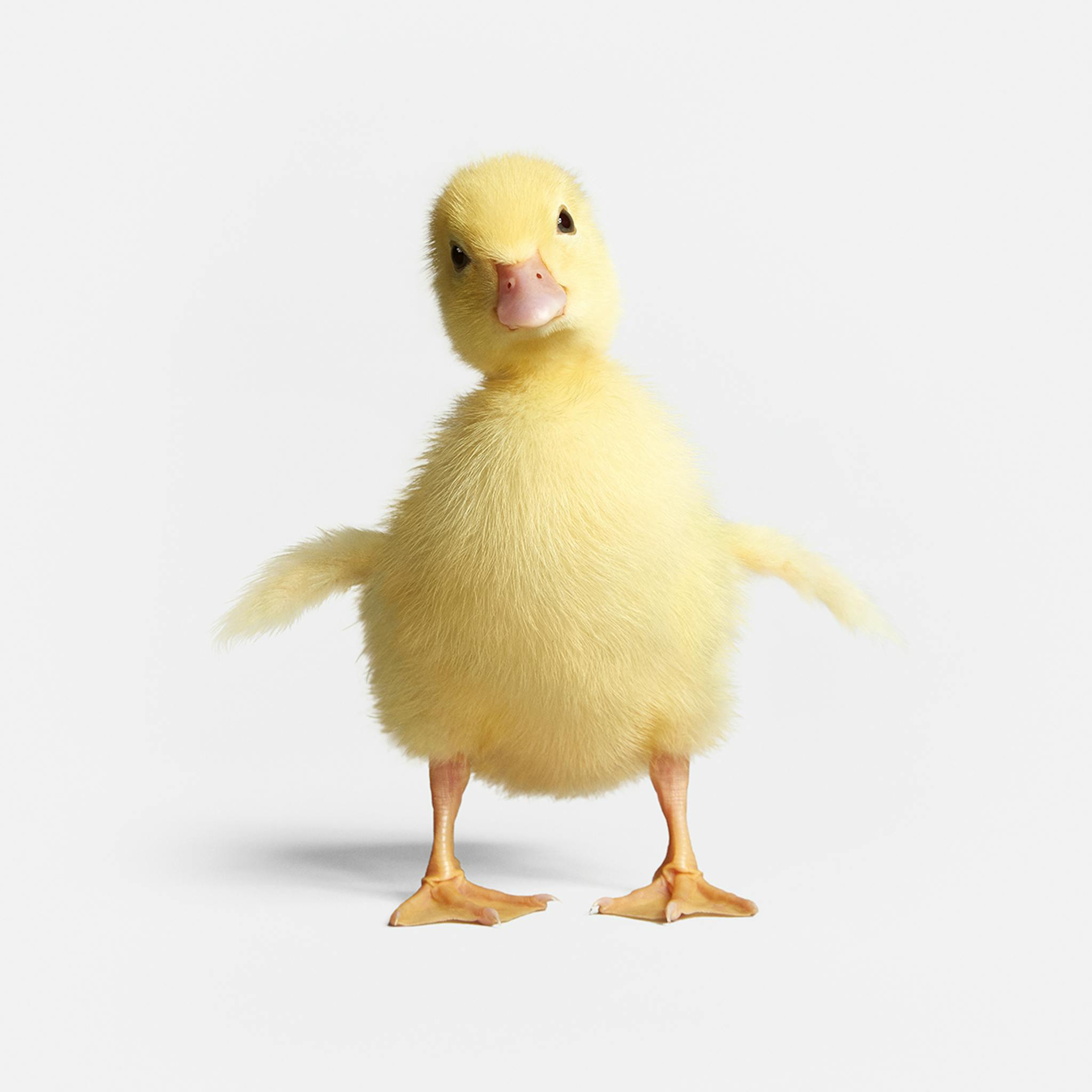

In The Animal Kingdom, Ford’s careful composition—the isolated animals against a stark backdrop, removed from the context of a traditional wildlife photograph—moves the images beyond glistening feathers and the elegant curve of a horn. The portraits convey a creature’s character. A black bull stands as tall as an arresting patriarch; a pastel yellow duckling cocks her head and lifts her wings in play. A chimpanzee, gazing into the distance and resting his chin on his fist, was modeled on Auguste Rodin’s sculpture The Thinker. (“My goal was to see if he would pose in a few very human ways,” Ford wrote.) But for even his most mundane subjects, Ford still aspires to the objective of portrait photography as defined by masters like Richard Avedon and Dan Winters: to illuminate aspects of who a subject really is.

Though he has been able to photograph both an African elephant and an American buffalo in studio, there’s one animal Ford hasn’t been able to get to sit for a portrait: his own pet, a thirteen-year-old cat named Harley. “She’s super skittish—she won’t even come near a flash,” he says. “Every time I use a camera, she darts away as if she isn’t going to have anything to do with me.” Turns out, a little black-and-gray tabby might be the most elusive subject of all.